Author: Moushumi Bhowmik

এইখানে কীভাবে এসে পৌঁছলাম আমি? How ever did I reach here?

মৌসুমী ভৌমিক

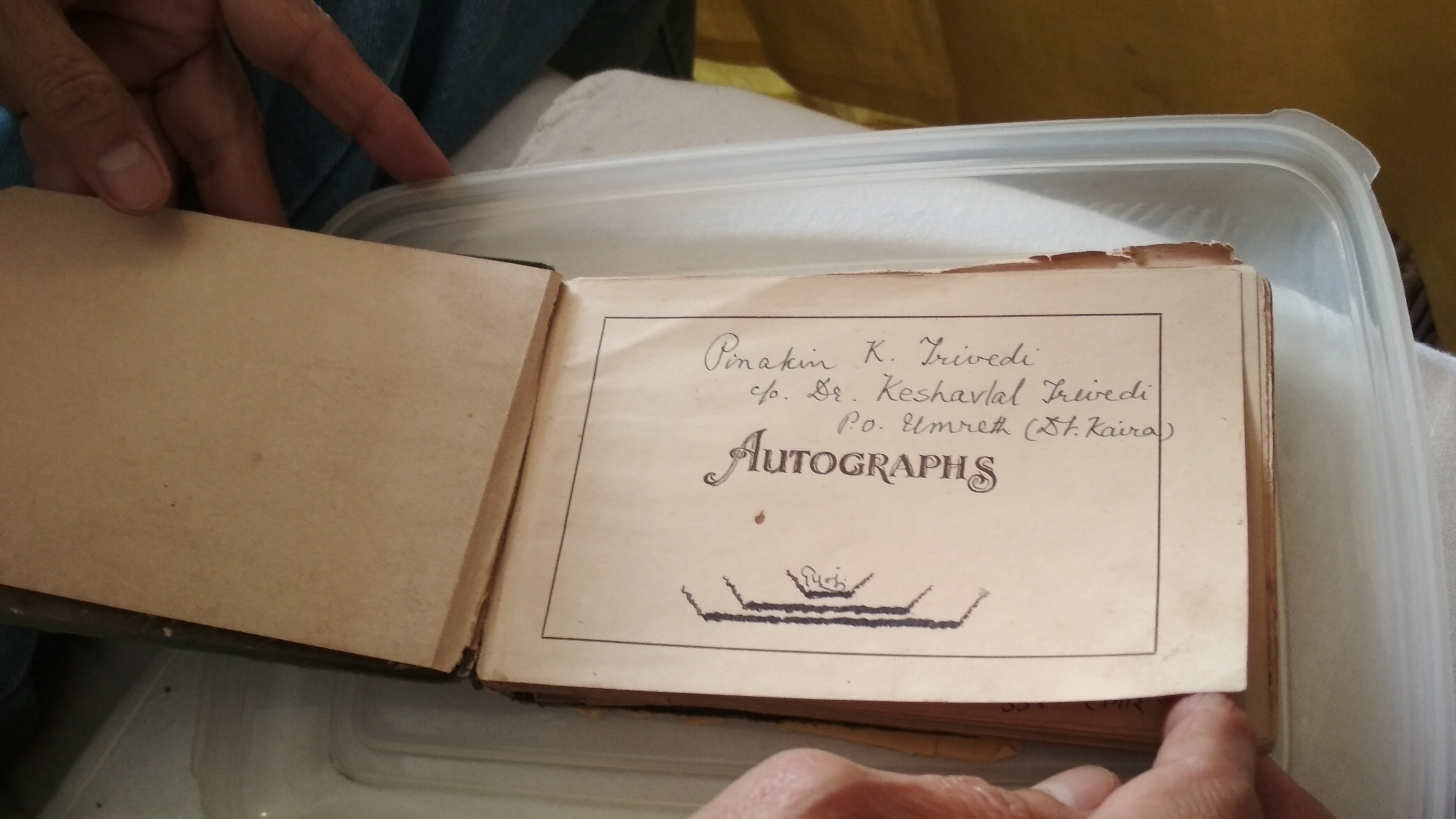

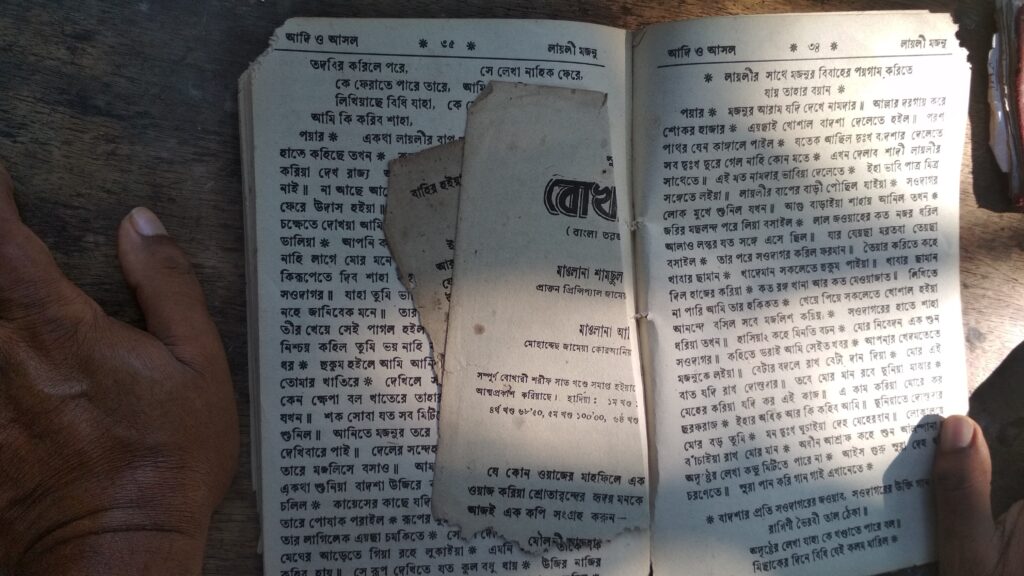

The Bangla book, Ekla Meyer Ghoraghuri, an anthology of women solo travellers, is edited by Sumita Bithi and published by Sumita Samanta of La Strada, Kolkata, January 2025. I am one of the writers but I write less about travelling alone and more about being not quite alone on the road. I write about the many faces and traces of sound, lives and loves that draw me out and pull me in.

My friend Debjani, who lives in Wahlwies in Germany, is central to my story as is the voice of Maria. Maria of Freiburg, we call her. It was a blessing to have heard her on a wet Sunday in October 2022.

My professional sound recordist/sound designer friends complain about the fumbling noises with which all my recordings start. That’s all right. You have to be a little patient. I am walking and recording, the mic of my recorder is brushing against my coat. I am not always aware of the angle of my arm. Then the tram comes, I have to stop, but now I have reached her. Debjani and I. She sings, we talk, she sings again, I hum with her. Beautiful she says. But the beauty was in that day, in Maria’s song and all the stories she has been leading me to.

On that trip in 2022, I was leaving Germany and going to France. I would take a train from Strasbourg. Debjani started with me, and said, I’ll come up to this point. Then she came some more. And some more. Till the border of Germany in Kehl. We crossed over to France by tram. Walked through the market, drank coffee, ate some food. I recorded a man playing accordion on the bridge.Then we went to the station and waited outside. We were sad to part. I was singing this song of D. L. Roy, and Debjani was recording me. How beautiful to be tangled up in love, to feel the pain, to be captive in our prisons of desire.

9 October 2022.

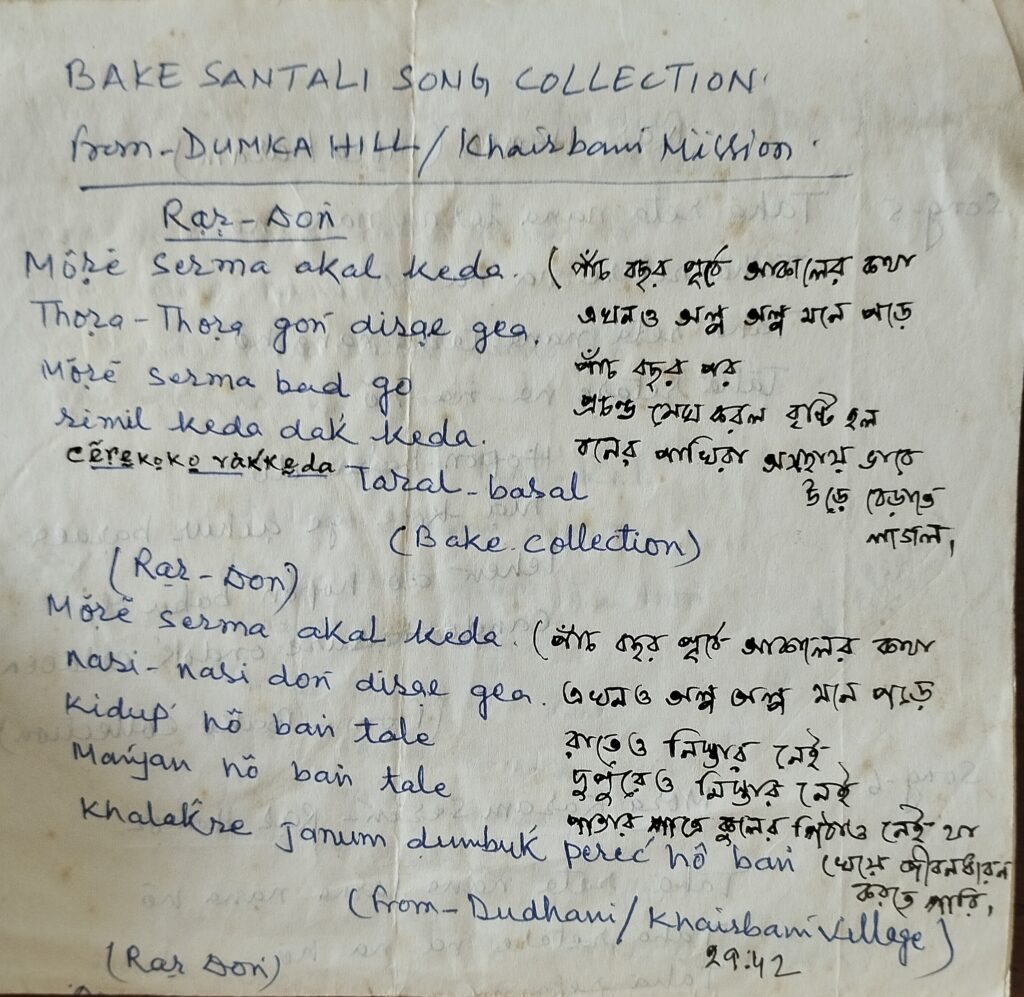

After 2017, I met several people, native speakers of Santali or scholars, with whom I listened not only to Bake’s Dumka recordings but also to The Travelling Archive’s, which came out of listening to those recordings back in the field. Hence it was a kind of exercise in listening to listening that we were trying to do together and recording that process. Listening, recording, listening again, recording that listening, listening to that recording, and recording again—time and voices and interpretations get layered one upon the other.

Those I include in this sub-chapter had an insider-outsider perspective to the recordings. With them, I did not need mediation to communicate, as we spoke a common language—by language, I don’t only mean English or Bangla, but we also had a shared vocabulary of thoughts and ideas. In a sense we were part of a community of our own. But they were also part of their home communities and there they became my mediators, helping me to formulate my questions and grasp the meanings of things.

I have been listening to Bake’s and our own Santal recordings with Rahi Soren, a young scientist who teaches in the Department of Oceanography, Jadavpur University, Kolkata. Rahi is keenly interested in exploring her culture and history and the politics surrounding them. With researcher and radio presenter Sitaram Baskey, she has been working on a project entitled ‘Resource Mapping the Early Recordings of Traditional Santali Songs’, creating an Archive of Traditional Santali Music

Rahi describes the Sohrai festival as they used to celebrate at home and questions of patriarchy within the community come up as she talks.

Rahi says that she has been trying to identify variations within the Santali language, by listening to migrant communities. ‘If you listen to Santals in North Bengal and Santals in South Bengal, or in Assam, you will hear differences,’ she says. The variations signal their different migratory paths and final destinations and the dominant language of the places which became their new homes.

Rahi hums tunes and explains the different forms of Santali songs and the meanings of words.

Our first round of conversation was in my home on 20 January 2021 and the above clips are from that session. Then, on 5 June 2021, we met over Zoom and talked some more. The following clips are from that round of conversation and they are interesting also from the technological point of view. I had a recorder placed on my table, Rahi is on screen, talking from her home. Hence the difference in the quality of sound. What is further interesting is that Rahi was playing to me recordings she had made while listening Santali programmes on All India Radio. This range of sound and recording excites me and once we learn to listen to these layers of sound, we can also listen to the many traces of time and place that the sounds hold in them.

We were talking about the Famine song that Bake recorded and all our listeners responded to (here is the response of the Kairabani listeners). I was telling Rahi about Father Solomon’s deeply perceptive and empathetic response to the song. I was connecting it with Father Stan Swamy’s life, politics and killing. Then Rahi said, we should also think about the songs which are absent in the recordings Bake made. Yes, absence in an archive is very important to understand a history of a time and place, I said. Rahi talked about the Hul seren.

She has written about how the Santal Hul (revolution) of 1855-56 was one such landmark revolt fought by the Santal Adivasis and lower caste peasants against the exploitative upper caste zamindars (landlords), mahajans (moneylenders), darogas (police), traders, and imperial forces from the East India Company in the erstwhile Bengal presidency. Then we exchanged books and recordings.

Let’s Remember the Hul (Disaibon Hul), by Ruby Hembrom and Saheb Ram Tudu (Adivani, 2016).

Disaibon Hul – An Adivaani book on the 1855 Santal ‘Hul’ Rebellion

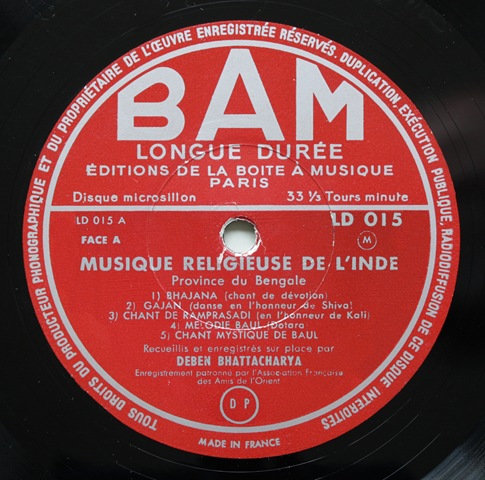

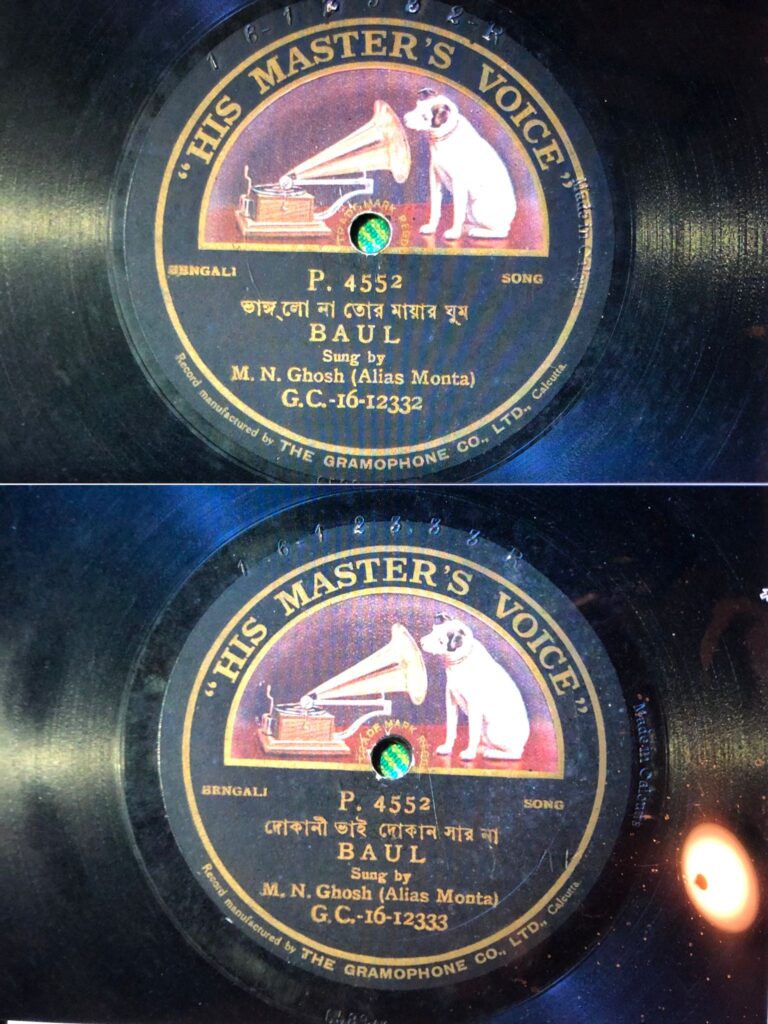

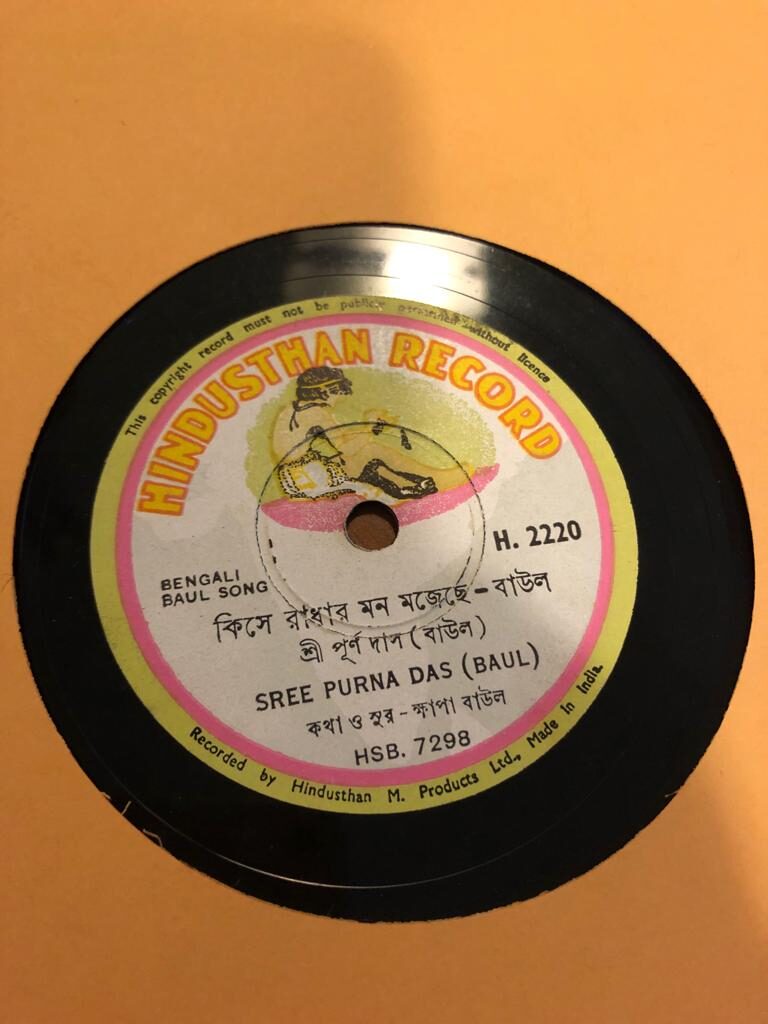

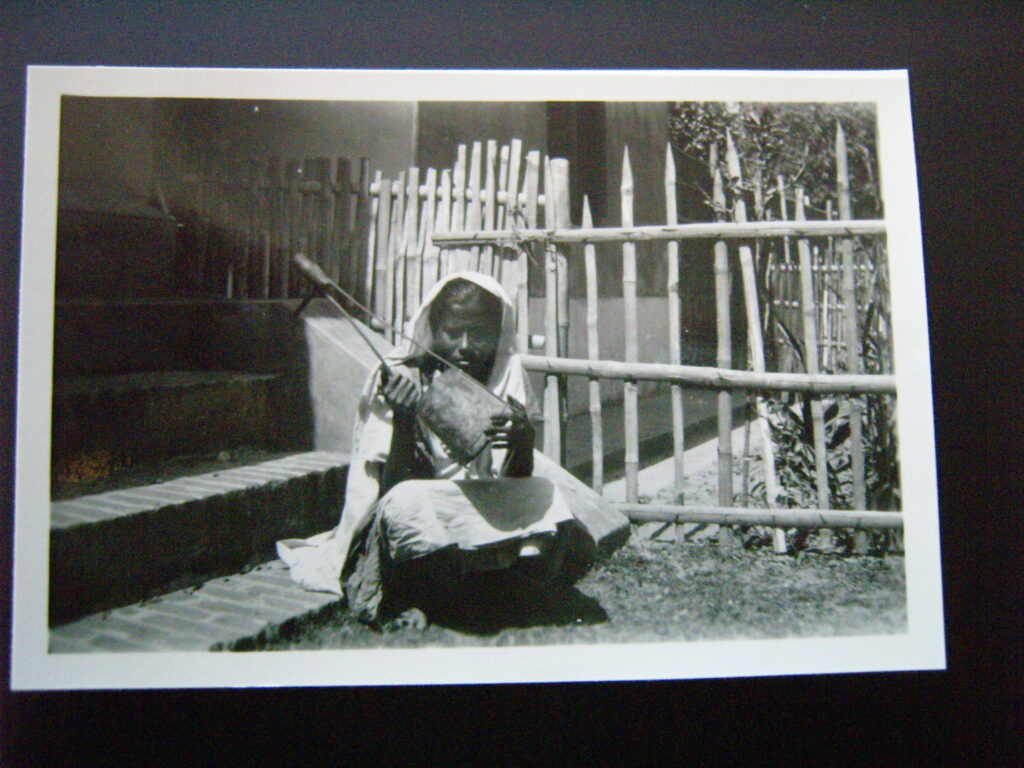

Deben Bhattacharya (1921-2001) , Bengali traveller, field recordist, broadcaster, records producer, filmmaker and translator, who spent many years of his life in Paris, had recorded the Santals near Asansol, West Bengal where they worked in mines and factories, in 1954 and later he came back to make a film, Belpahari: Faces of the Forest on them in 1973. Richard Lannoy, Deben’s photographer friend, had taken a now famous photograph of Deben seated on the ground while a group of Santal women and children look on.

Ayo Kukire Gel Bachhar, a song recorded by Deben Bhattacharya.

Deben Bhattacharya had recorded a Hul seren and Rahi sent me a video with his recording and a more recent recording of the same song. She sent me the words of the song too, which she translated for me.

The words go: ‘Debon tingun Adibasi bir do/Debon tingun Adibasi bir/Marań buru jó me̠nabon/Mit’ho̠rte taram abon/bạiri he̠le̠ćkate abon/Duk Do mabon ńe̠lńir/Debon tingun Adibasi bir do/Debon tingun Adibasi bir.’ In Rahi’s translation, they become: Let us stand together, o brave adivasi /Let us stand together, o brave adivasi /Let us praise the almighty, marang Buru/Let us walk together on the same path/Let us wipe off the enemy and leave our misery/Let us stand together, o brave adivasi /Let us stand together, o brave adivasi.’

Rahi and I have continued to talk. She has introduced me to the writings of Nishaant Choksi, sent me links to interesting archival work and exhibitions on Santal music , reminded me of the recordings of George A. Grierson made in 1914—perhaps the earliest ever.

This recording, made for the Linguistic Survey of India, can be heard here. I was playing from my laptop and recording as I listened. In my recording, a dog can be heard barking, even the hum of my refrigerator.

I saw a song and dance sequence in a recent Bangla film featuring Santals and was thinking what Rahi might think of it. The song is in a kind of Bangla that is supposed to represent Santal-speak. She said, there is nothing new in this. ‘Beshirbhag cinema tei bipul misrepresentation dekhechi aage’ (I have seen such massive misrepresentations in most films in the past.) ‘College e poraten ek mastarmoshai jigges korechilen ‘Baha’ TV series e jemon kore prodhan choritro kotha bole, serom bhasai barite kotha boli kina.’ (There was a teacher in my college who asked if we spoke at home like Baha of the TV soap [Ishti Kutum]).

On 9 May 2022, she sent me her own recording from a recent mela in Jhilimili. You will like this one, she said. It is an annual festival. Of course, dancing at home and dancing in a fair are not the same, she reminded me.

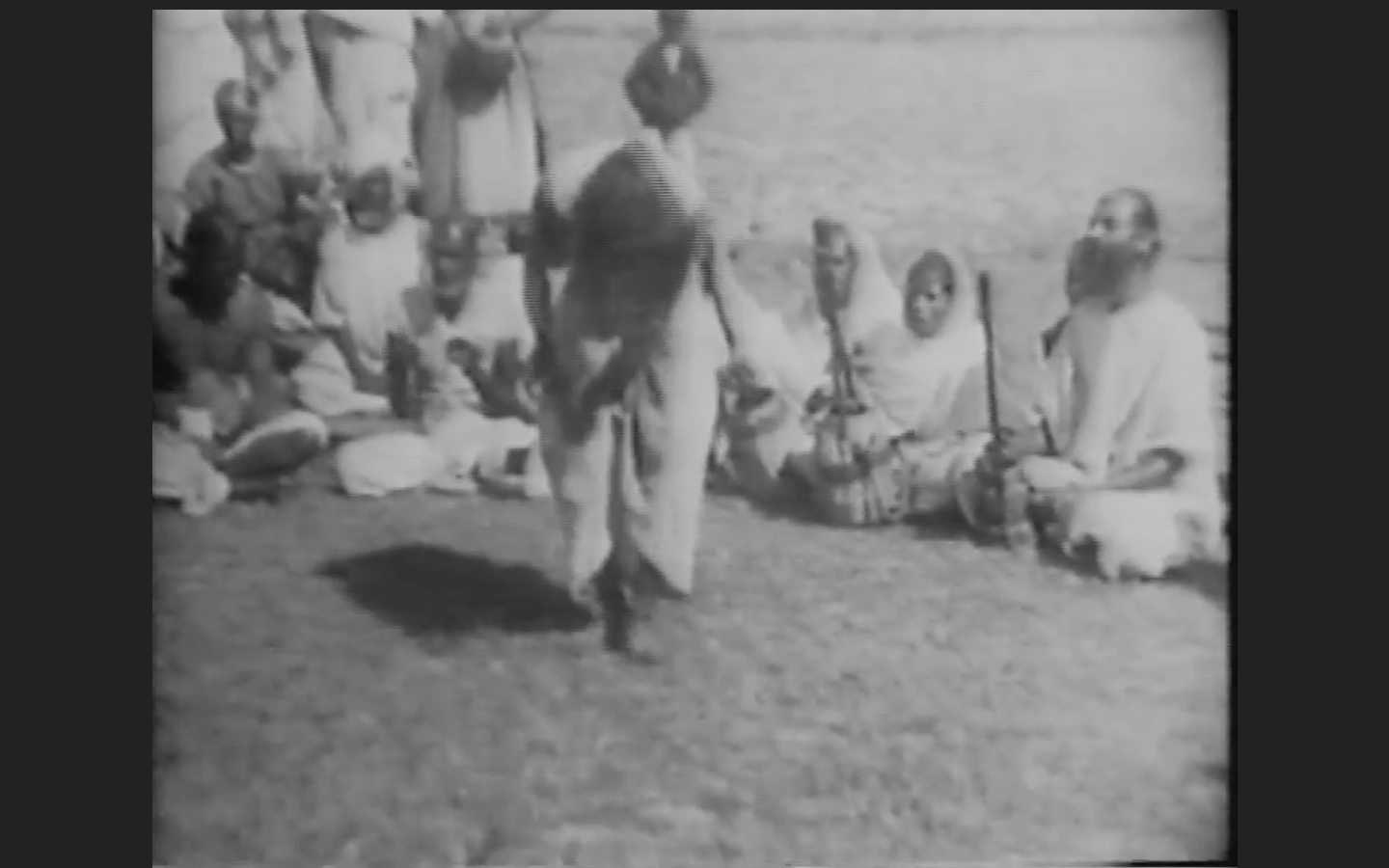

This is the note that Rahi sent. ‘Come spring and a quaint little village in Poradi wakes up to the sounds of the Tamah and Tundah at dusk. People from near and far gather at Jhilimili Pata for the night and disperse with the first light of dawn. I was honoured to have been invited to one such event and to witness the amazing gathering and people bustling throughout the Pata. This gathering has been a platform for the revival of Santali culture, religious sentiments as well as for book lovers and merrymakers. The dance form in this clip is one such performance where dance troops came from Bandwan, Khatra, Jhilimili and Ranchi to showcase their talents in rare dance forms. Over the years, people from the community have also learned and re-learned several dance forms which are now threatened with extinction as there are now more ‘popular’ and easily available entertainments for the masses.’

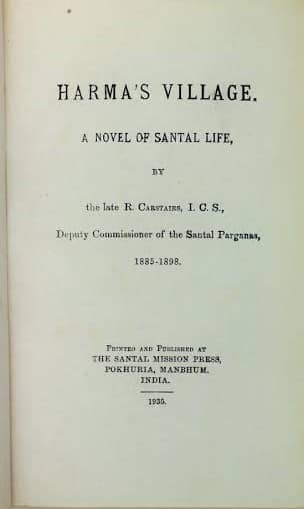

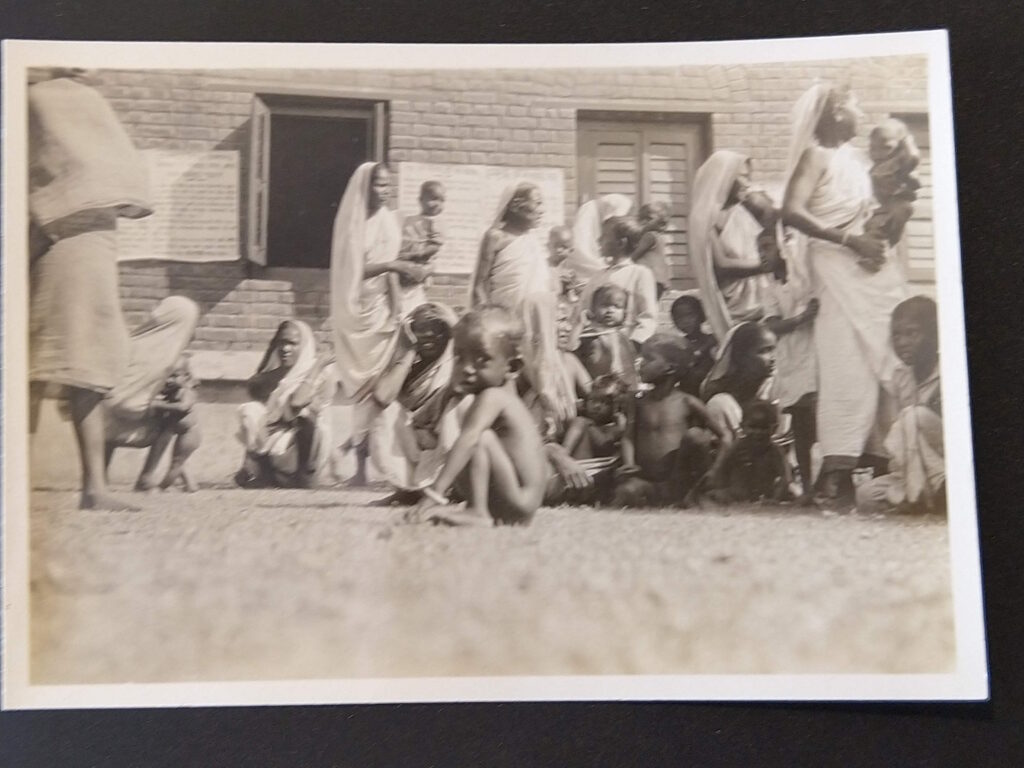

Title page of the novel Harma’s Village, by Robert Carstairs. Photo: From the wall of Soumitra Sankar Sengupta on Facebook.

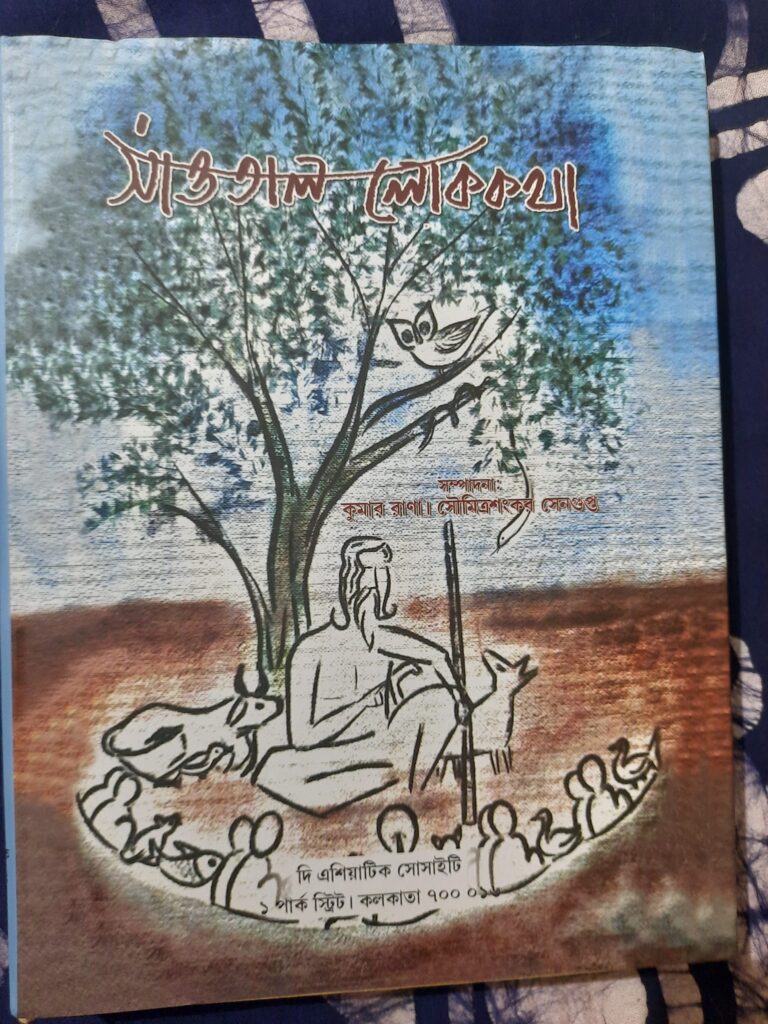

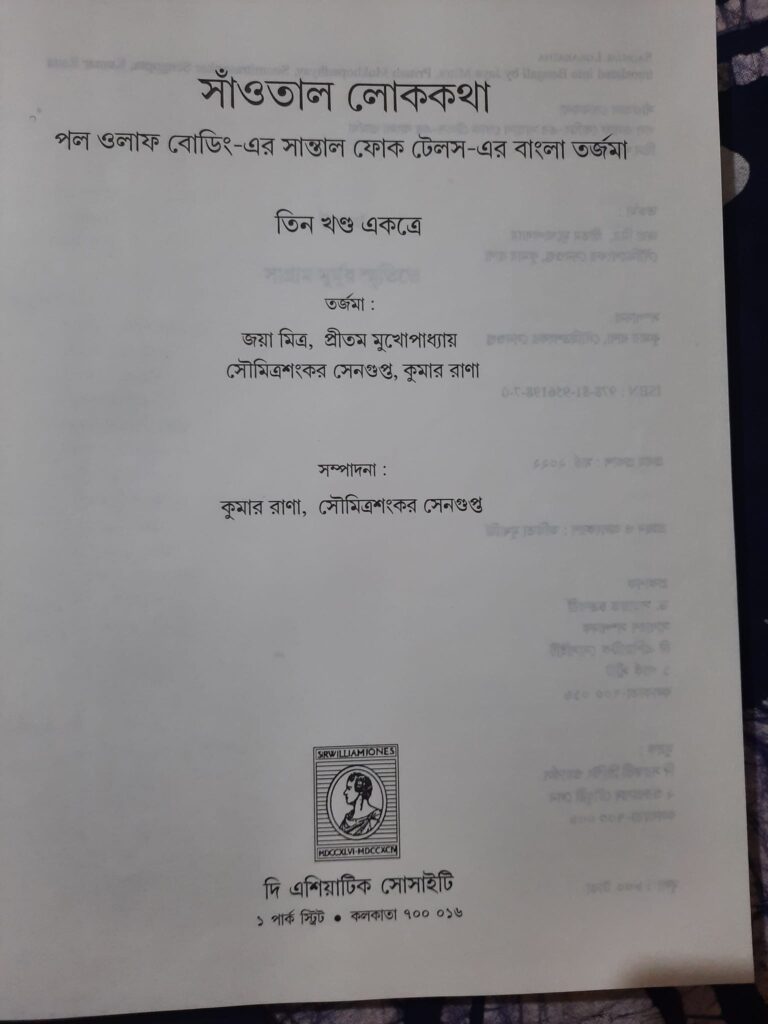

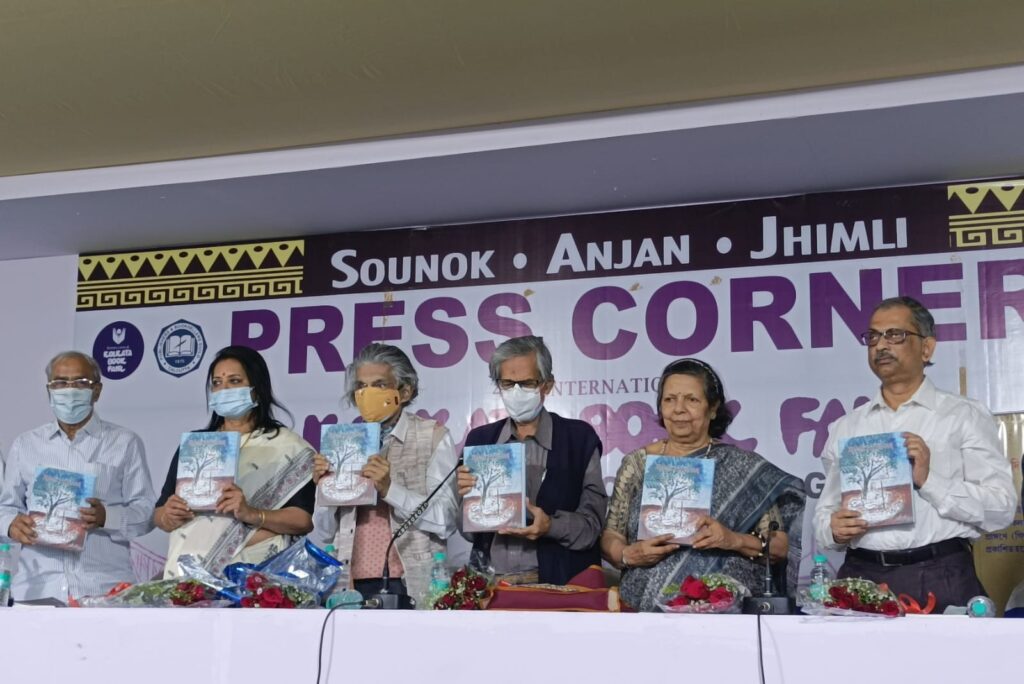

With Soumitra Sankar Sengupta, an avid reader and collector of books and a writer, also a civil servant, my connection started with a post he had written on Facebook in 2020 on the night before the anniversary of the Hul rebellion, which deeply moved me. It made me write to him and he wrote back and that was the opening of an ongoing conversation, where I mostly question and he answers. Anyway, in this ‘first post’ so to speak, Soumitra wrote about how he had first learned about the Hul from his uncle (his mother’s elder brother), an exceptional teacher in a village school in Birbhum, the headmaster, with whom he went on morning walks, talking and listening along the way. They went up to the narrow stream at the edge of the village and came back home. His uncle washed his feet and entered his study, young Soumitra followed him inside. There was a yellowing map of Birbhum on the wall of this study and many photographs too and books on his desk. They triggered the boy’s curiosity. One framed photograph carried a caption, ‘The banyan in Panchkathia village under which the Santal rebels killed [the word used is boli where the act of killing is a sacrifice, an offering made for greater good; I am not sure how to translate it] Mahesh Daroga’. Soumitra browsed through his uncle’s books. An assignment to transcribe parts of an old manuscript (History of the Santal Hul by Digambar Chakraborty) from a weathered foolscap exercise book, a trip to the Tantlai hot spring on the border of Bihar and Bengal, near the Siddheswari river —all these little things gave young Soumitra the feeling that he was standing within the pulsating heart of the Hul rebellion. Those were the beginnings of a lifelong love of books for Soumitra which taught him to think and write. He felt almost compelled to understand the land he was walking and the people he was meeting and the lives of those who had walked on it before him. Later, when he became an officer in the state administration, he knew that the system had its limitations, but many before him had worked within those limitations and he drew inspiration from them. He chose a path of knowing the land. Around 2004-05, Soumitra came across a chapter of a novel on the internet, which described the killing of Mahesh Daroga in Panchkatia, returning him to the picture on the wall of his uncle’s study. That book was Harma’s Village: A Novel of Santal Life, written by Robert Carstairs, ICS, Deputy Commissioner of the Santal Parganas from 1885-98 and it was published by the Santal Mission Press, Pokhuria, Manbhum in 1935, many years after the author’s death . Later, Soumitra found a Bangla translation of the book, by Subal Mardi, a senior bureaucrat with whom he had also worked. That book was not a direct translation from the original English, but from R. R. Kisku’s Santali translation. He also came across another slim volume entitled Jangale (In the Forest) by Satishchandra Mukhopadhyay which, he realised, was based on Harma’s Village. Many more encounters occurred, with books and real people, that led to the deepening of Soumitra’s relationship with the land, language and life of the Santals. Earlier this year, in March 2022, Asiatic Society, Kolkata published a Bengali translation of Rev. Paul Olaf Bodding’s three-part Santal Folk Tales, edited by Soumitra Sankar Sengupta and Kumar Rana, with contributions from Jaya Mitra and Pritam Mukhopadhyay.

I just had to start talking about Bake’s recordings in Kairabani and the Dumka Mission and Soumitra knew far more than I did, although the matter of the archival recordings was new to him. He said there was probably some mention of the school band and of the music teacher Jacob Soren in Olav Hodne’s The Seed Bore Fruit (1967). By the evening, he sent me pages from the book.

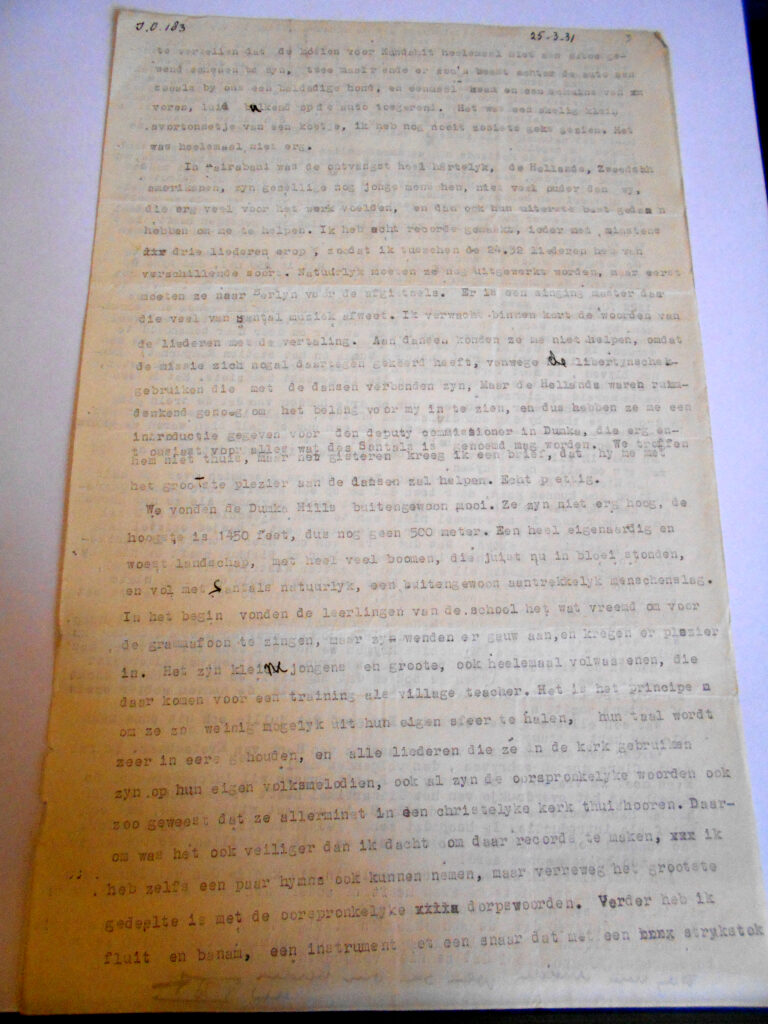

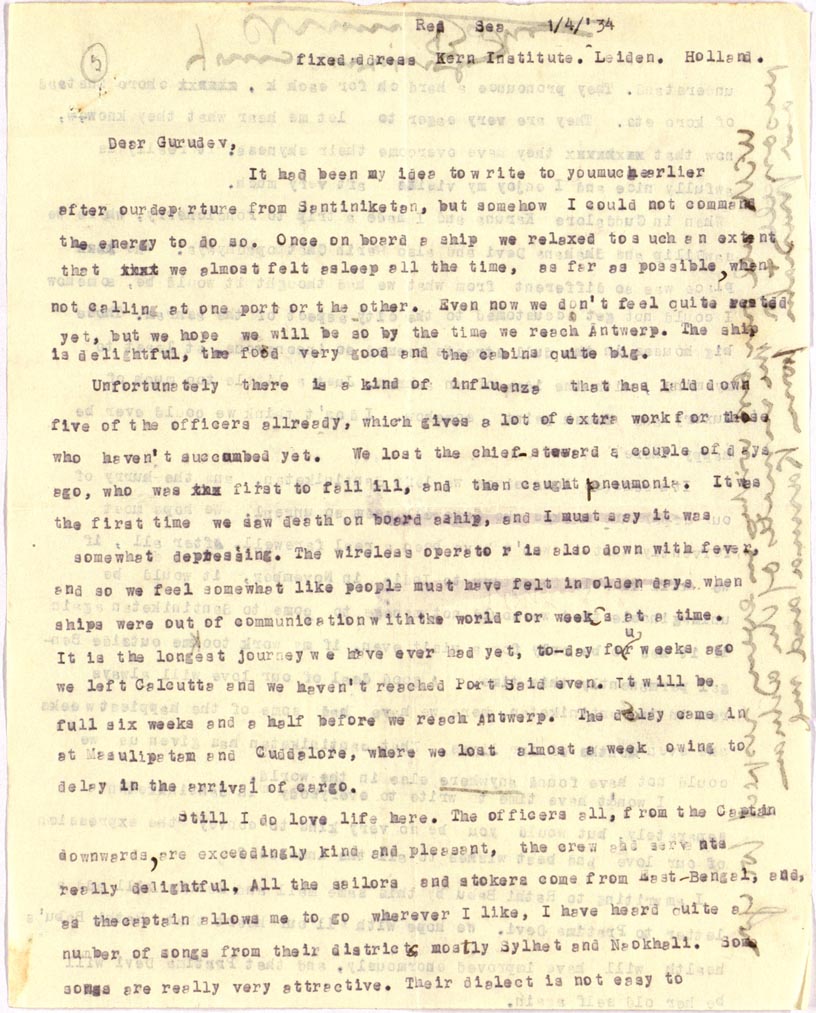

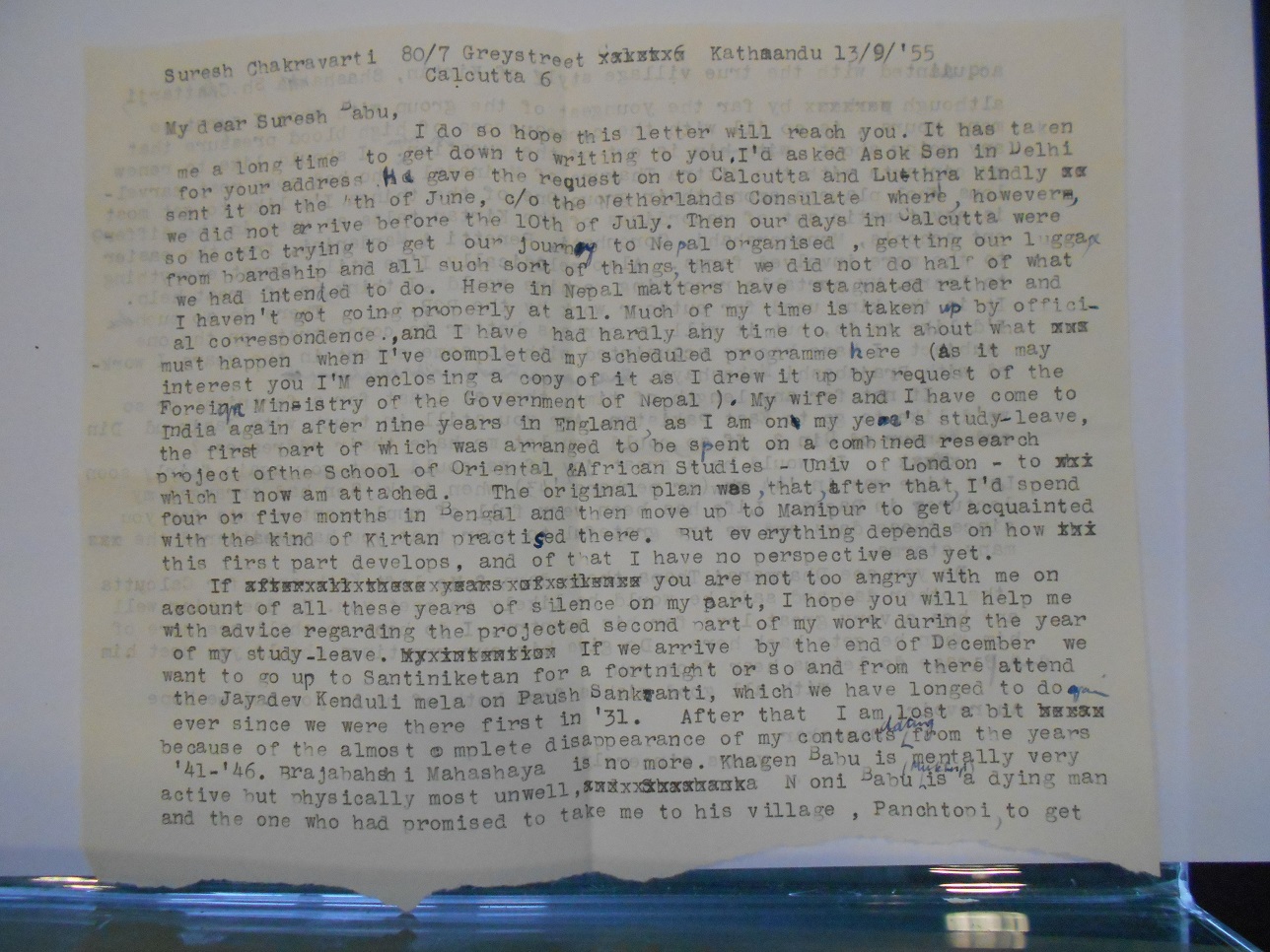

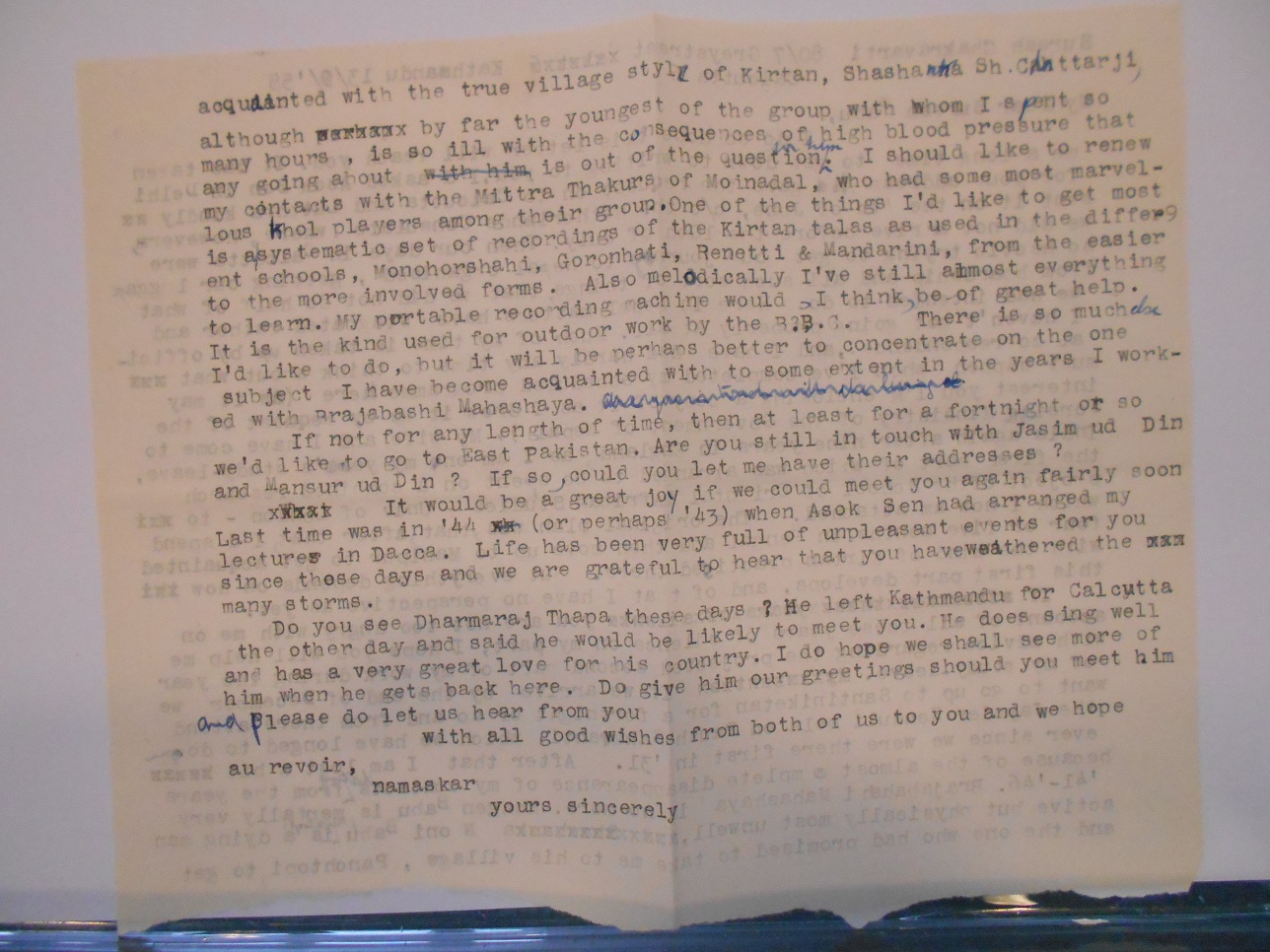

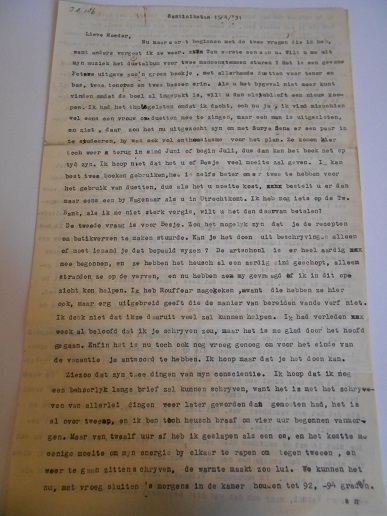

Arnold Bake had written to his mother on 25 March 1931 that he could not record dances in Kairabani but he would try and meet the district commissioner who was apparently interested in such matters and then come back and make more recordings.

Page from Arnold Bake’s letter of 25 March 1931, written to his mother. Photo of this letter was taken when I was working in Leiden University library in 2015.

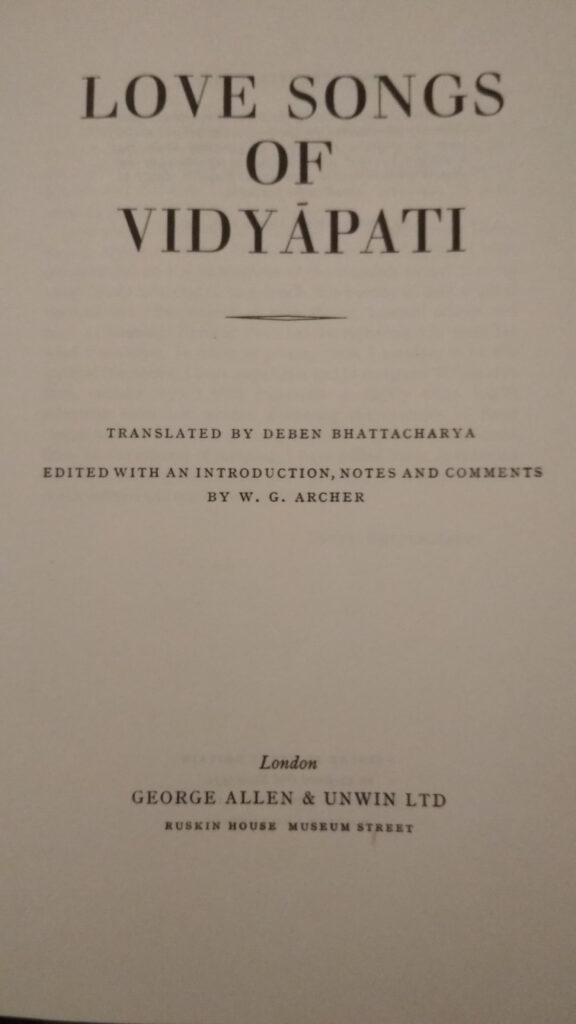

So, one of the questions I kept bothering Soumitra with was, who was this District Commissioner Bake was writing about? Give me two days, he replied. Then in an email of 3 March 2020, he wrote, ‘Are you talking about W. G. Archer? He wrote about Santal life, poetry and song in his Hill of Flutes. Archer joined the service in the Santal Parganas in 1931, but he was not a DM, he was an assistant magistrate.’ Names come with their own associations. W. G. Archer also wrote the notes and introduction to Deben Bhattacharya’s Songs of Vidyapati and I had a copy of the book.

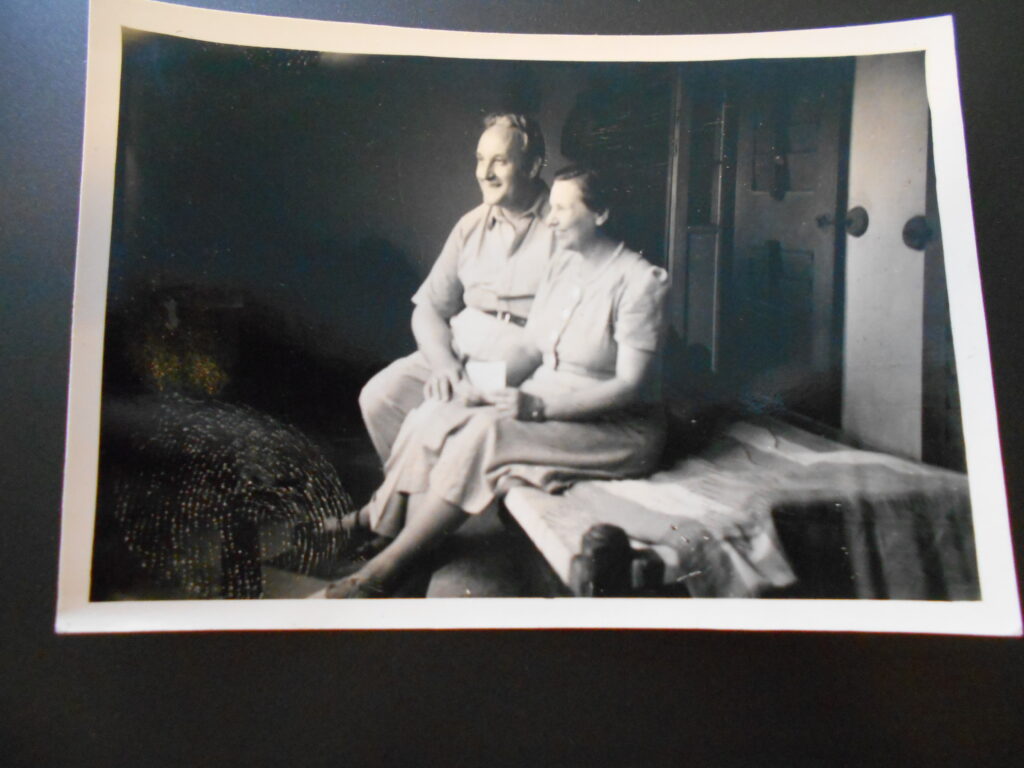

How archives are interwoven in this work. Our personal archives and the institutional archives become part of the same story, one leads us to another. I was in Deben Bhattacharya’s home in Paris in 2019 when his widow, Jharna Bose, the true keeper of his memory, gave me a copy of this book. It was for me like bringing back a handful of soil from an archaeological site.

As we already know, Debenbabu had recorded the Santals in 1954, two decades after Bake, and then again in 1973, and he could record both dance and the Hul seren! Everything seemed to be connected with everything. I got hold of a copy of The Hill of Flutes: Life, Love and Poetry in Tribal India: A Portrait of the Santals (first published in 1974 and republished in 2016), and was struck by its sheer depth and range and wondered how, just how people managed to do so much work in one lifetime.

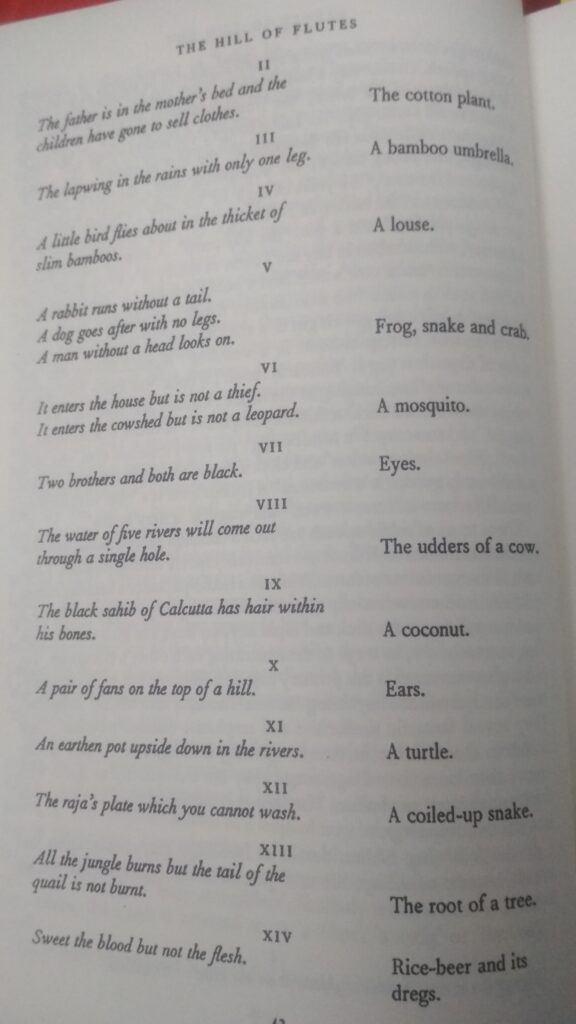

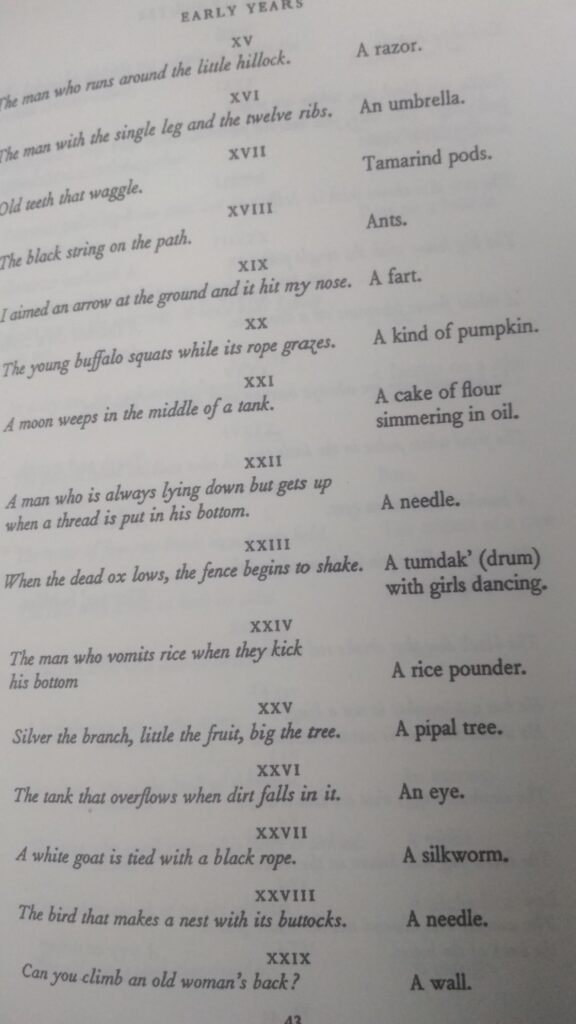

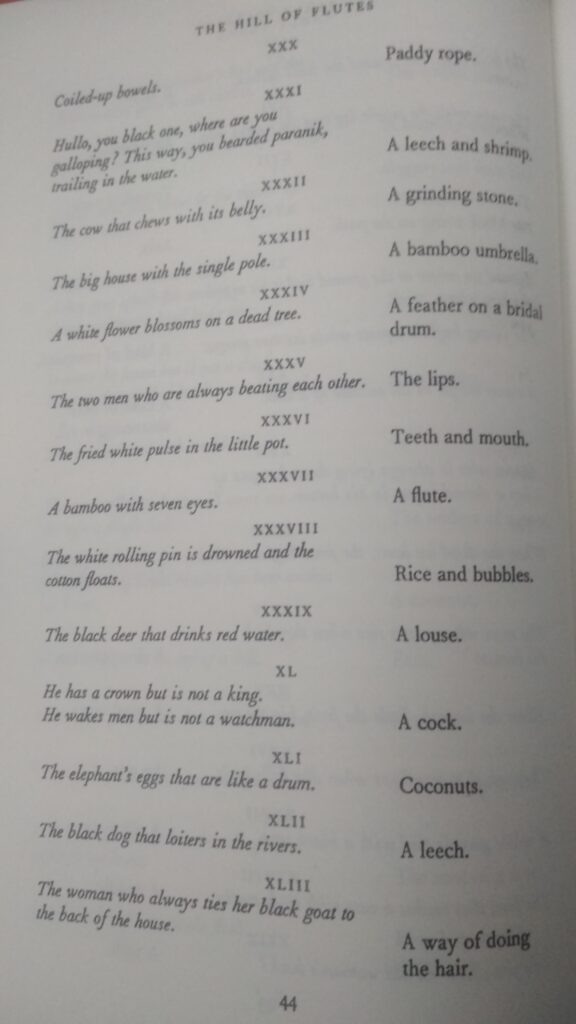

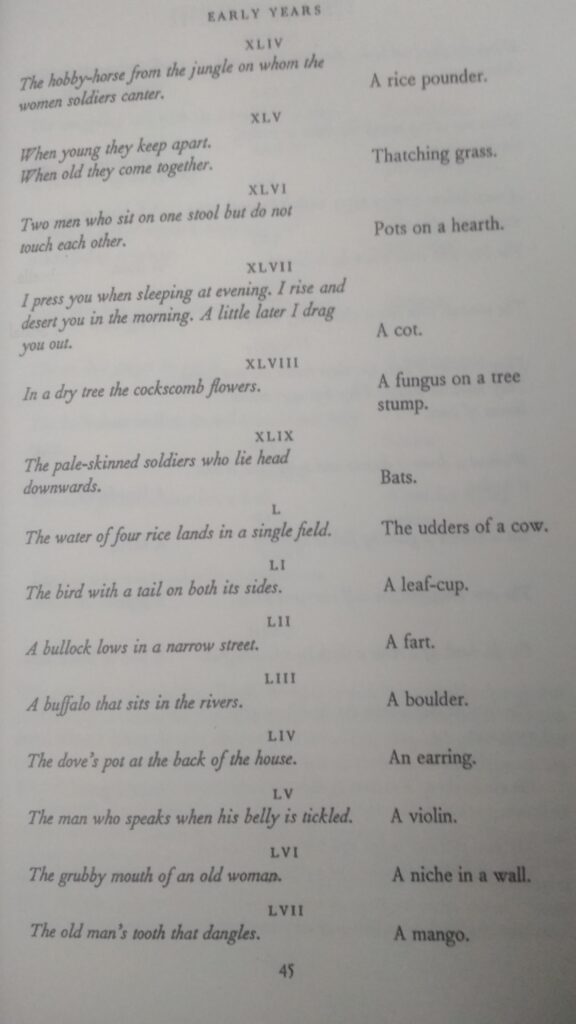

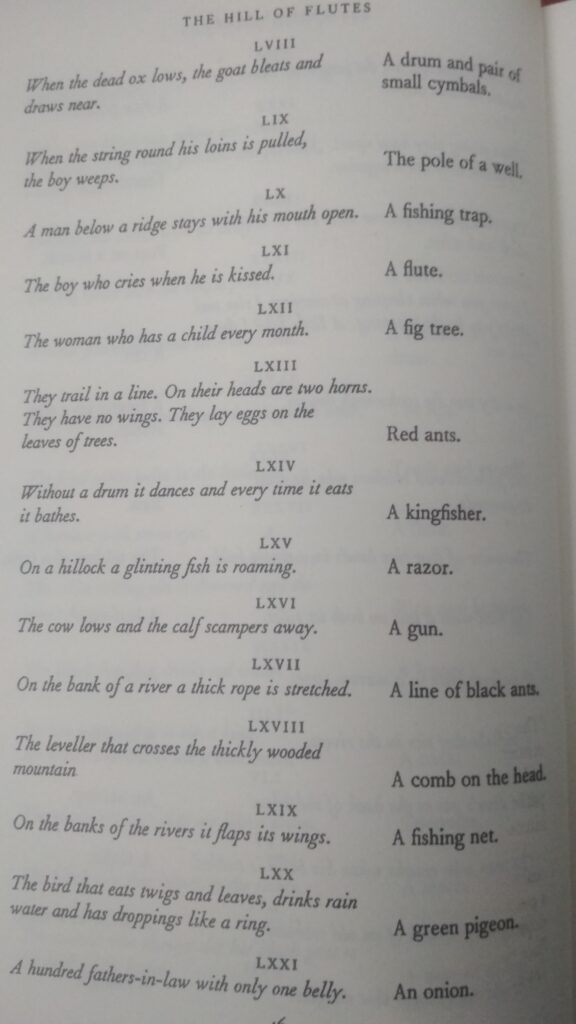

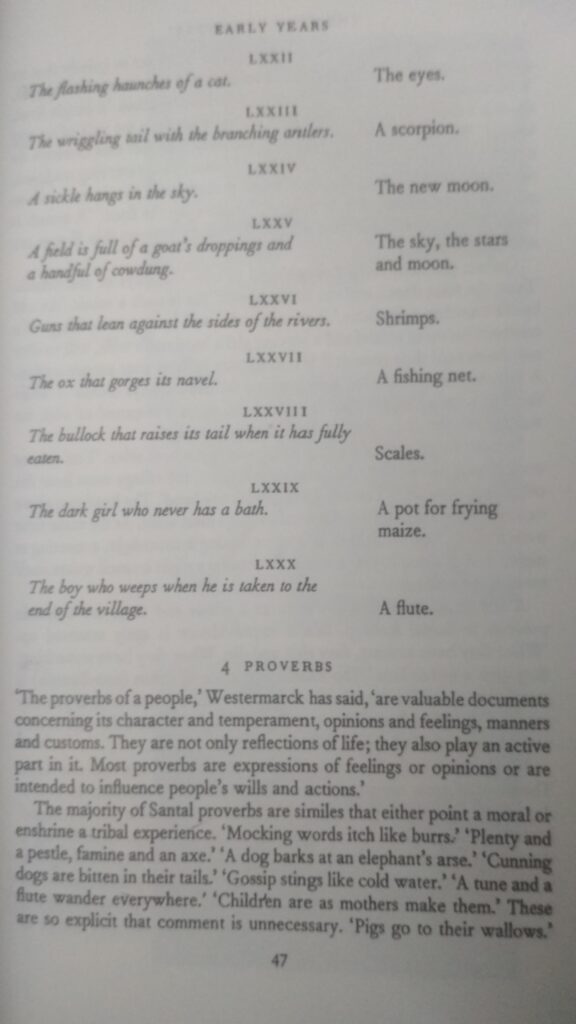

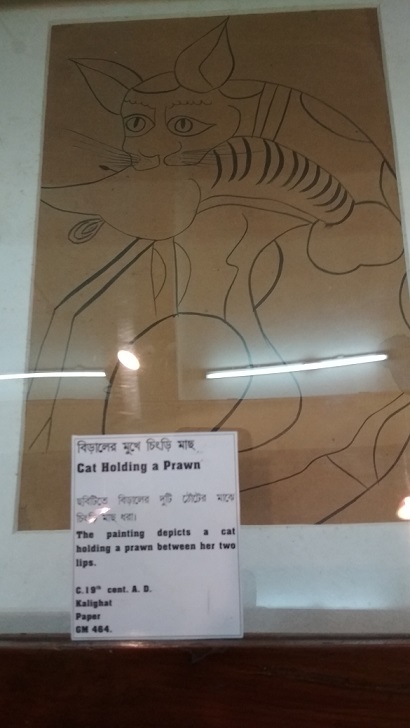

What is a recording and how does one make a recording, even a sound recording? Here are some pages from W. G. Archer’s Hill of Flutes in which he lists the many riddles he had collected from the Santal Parganas. He wrote: ‘In the following riddles, day to day sights and sounds, aspects of village life and general Santal behaviour are widely invoked.’ I like the word ‘invoked’, the awakening of the sonic and visual, the record of the everyday lives of people through sound and image. Or, recording sound and image through text. Not a direct description of a sound, but a metaphorical, abstract way of talking–a flute is ‘a boy who weeps when he is taken to the end of the village.’ At the same time, if this list also had a transliteration of the riddles in Santali, then the reader would also hear something of the sound of the original language. Below , a piece of Archer’s ‘sound and image archive’.

Have you read From Fire Rain to Rebellion by Peter Anderson, Marine Carrin and Santosh Soren ? This both Rahi and Soumitra asked me. And when I would get stuck with something, they would take photos of pages from their own copies and send to me. Then, as I was writing and writing more, and when I was going back again and again to Bodding’s work or to Archer’s like I would go to a library, and I also saw Rahi and Soumitra doing the same, I had to ask them the question on my mind: what then did they think the role of the missionaries or colonial scholars had been? Soumitra quotes Jomo Kenyatta on his Facebook page; that is his opening statement.

That would make the explanation fairly simple. But isn’t the question more complex, more nuanced? Weren’t there many more layers to this history? He wrote me a beautiful email in response, which I want to keep here in the original Bangla.

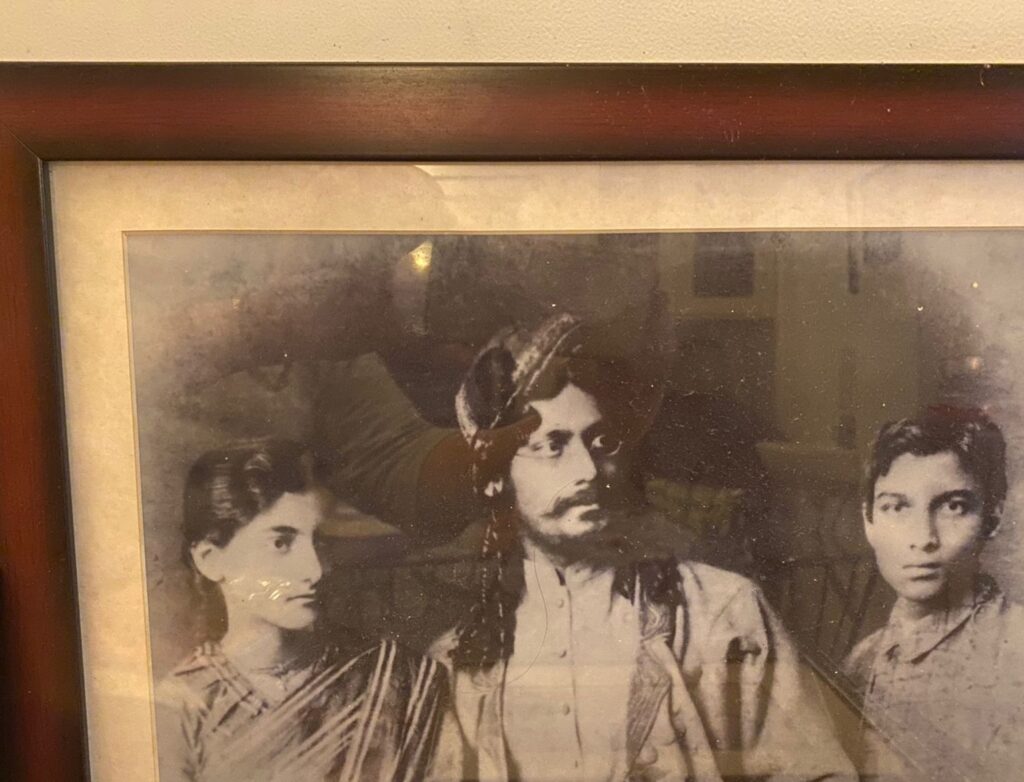

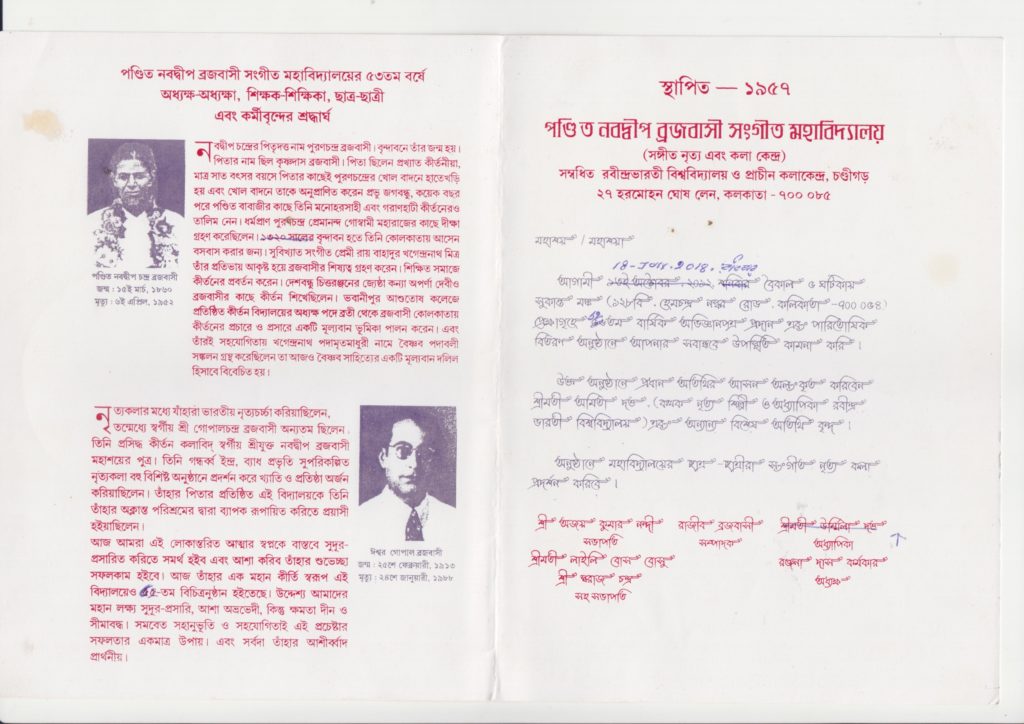

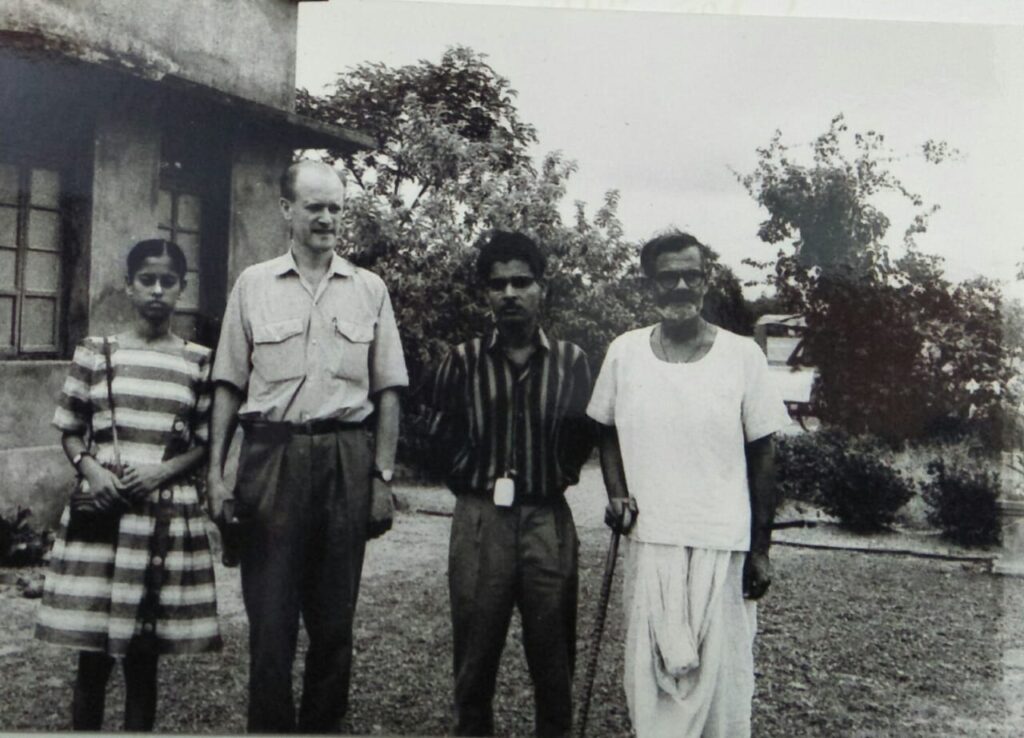

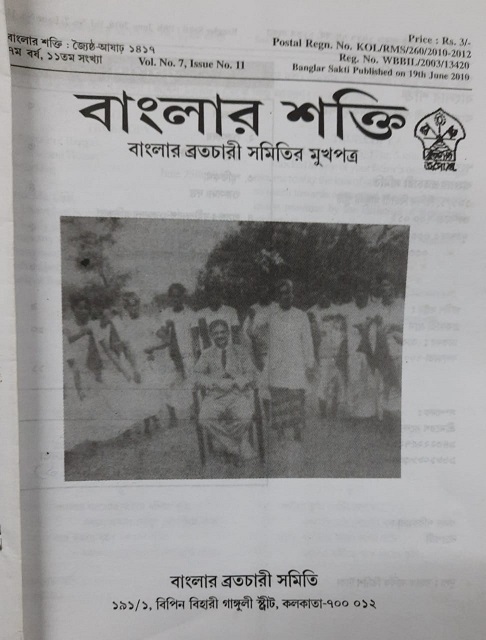

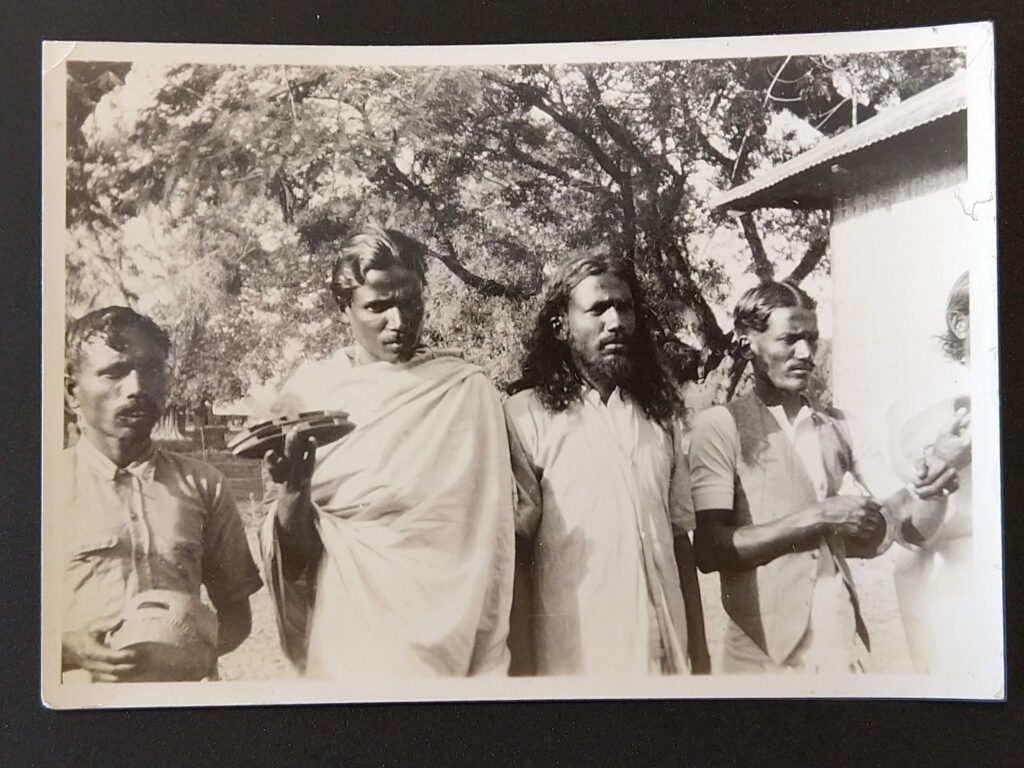

Soumitra Sankar Sengupta (extreme right) with others at the launch of their translation of Bodding’s anthology of Santal folkllore

I will come back to Soumitra again, but for now I want to write about two other Santal scholars and poets who helped me understand Bake’s songs and our recordings in Dumka. One, Susil Mandi and the other Biswajit Hansda, both young students of Jadavpur University, who came over to my home and listened with me to the recordings. We met over three evenings, on 16, 26 and 31 March 2019. My recorder broke on the second day and so the recordings were made on my mobile phone and the quality is poor, but the content of the recordings is lively and full of new ideas. As I have listened back to my recordings and interactions with Rahi or Soumitra or Susil and Biswajit, it has struck me how differently we perceive the same thing, how much of what our concerns are depends on where and how we are socially, culturally and politically located. Sushil, a political activist, talks mostly about social inequalities, Biswajit, barely 21 years old, is very literary and is thinking about words and translations and poetry and books. Rahi talks more about gender relations. Soumitra, older and wiser, has seen more of life. He works meticulously towards building and keeping an archive of archives. And finally Subhomoy Roy, a very young Bengali student of Santali at Visva Bharati, knows but uses his Bengali literary references to understand things, and then he has turn to his Santal teacher to ask for the meanings of things.

Recent photos of Susil Mandi and Biswajit Hansda which they sent to me. I did not take any photos when they came to my home.

I listened with Susil and Biswajit to the Kairabani recordings that we had made in 2017 (listen to some of those recordings here and in my other sub-chapter on the Santal recordings of Bake). They were interpreting the Santali conversations and adding their comments, while I was asking questions based on what I could hear. I thought I heard them say Marang Buru and then we talked about the importance of mountains in the Santal worldview and the place of mountains in the perpetuation of life on earth, and why the Santals worship the tall (marang) mountain (buru). Out of the two voices, Biswajit is younger and faster-paced, with high energy. Susil pays more attention to his utterances; he is the artiste. Recorded on 26 March 2019

The Arnold Bake recordings from Dumka began with a flute which the Kairabani listeners had identified as the flute played during their sikar or hunting festival. Sushil and Biswajit explain here the meaning of ‘disom sikar’ in which people from all around gather to take part in this communal hunt and merrymaking with music and dance. Recorded on 26 March 2019

What is the sohrai? Is it a harvest festival? I talk with everyone about the same thing, but never fully understand. Because there are many stories about the same thing, many descriptions and explanations. So, I suppose what I need to understand is that sohrai is not one thing, but many things. Such as Dasae is too. And how we describe something, with what references, shows how to relate to the world and what constitutes our worlds. Susil said sohrai was like nabanno, the Bengali harvest festival around new crops, nabo meaning new and anno meaning rice. No one else I talked to had drawn up this reference. Does that mean he is too assimilated into Bengali culture? Not quite. It means his world can hold other worlds and other references too. At the same time, he says what is special about Sohrai, what is uniquely Santal. Because it is not just about humans and their relation to the land, but it is also about other living things. During sohrai, animals of the house, such as cows, are decorated with colour and given special food, while trees are also at the centre of the celebration. Recorded in Jadavpur on 26 March 2019

They talk about different kinds of songs, what song is sung when, the difference between the songs and rituals of those who have stayed back in the land of their ancestors and those who have had to move to other places for work. About the dominating language and the dominated language. Such as Rahi had also said. Then Biswajit sings two don serens.

I had asked about the ‘lagre’ and if, etymologically, the words don and lagre had any special meaning and at first Biswajit said he would have to go home and think and would come back and tell me. Then he thought some more and said there was something he had heard about the word lagre having something to do with invoking rain. Lara means to shake up something and when clouds like the unmovable body of an elephant stick to the sky, there is the singing of the lagre down below, in the centre of the village, to bring down the rains. From lara comes lagre, he said. Even Susil was just listening to him. Whether what he was saying made any sense or not I would not be able to say but from one word we went to another, from thick elephant-clouds to flaky cottonwool, from rimil to rahla. This play of words went on for some time, and then Biswajit said the Kalidasa’s Meghdoot had been translated into the Santali by Shobhanath Besra and it was called Rahla Raibar, raibar meaning doot or messenger. I cannot say anything more about this exchange except that I liked to listen to their conversation and like to listen and learn about lives which are lived right by my side but about which I know so little.

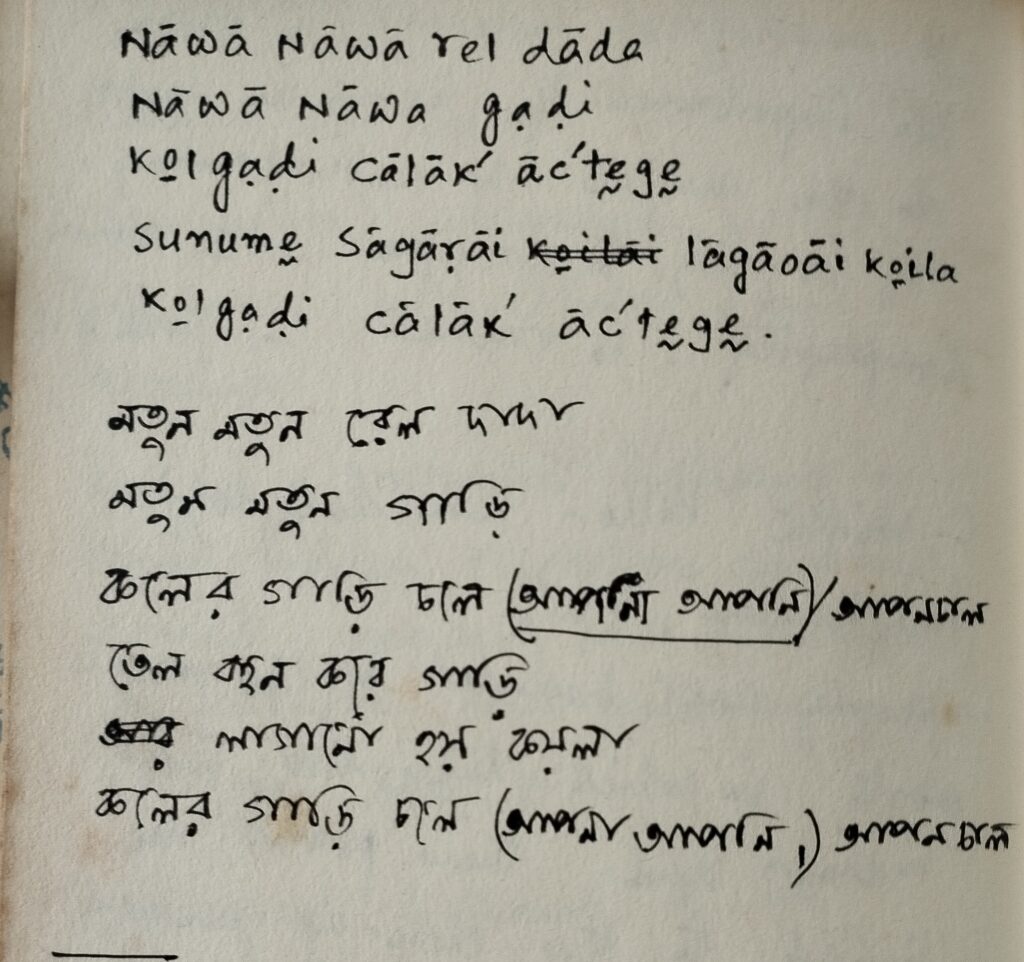

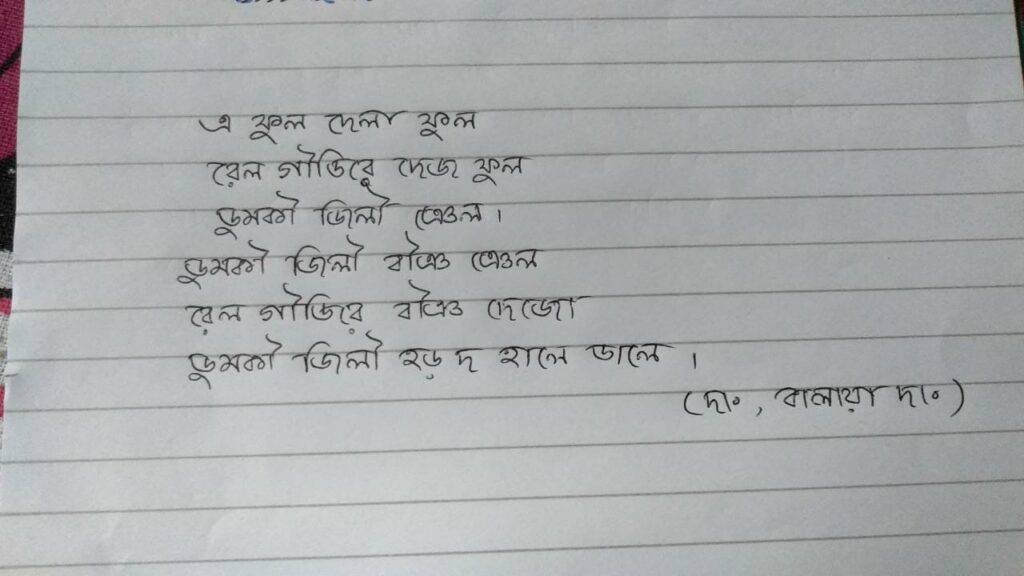

When we listened to the famine song that Arnold Bake had recorded and then to the one we recorded in Kairabani, Susil wrote down the words for me. Then we came to the locomotive song and what Susil wrote was so close to the rhythm and scansion of what we were hearing in the recordings that I began to sing his words, and together we made a song!

The ‘koler gari’ song, sung by Moushumi, Biswajit and Susil Mandi, on 31 March 2019.

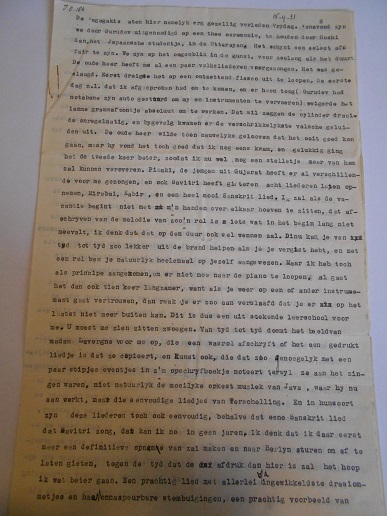

Subhomoy Roy, a student of Santali in Visva Bharati in 2018 (teaches in a school since 2021), had connected with me for something to do with my songs and then when we got talking and he told me that he was specialising in Santali, I found that unusual. I told him about Bake’s recordings and mine. Then we met in Santiniketan and in Soumya Chakrabarti’s house we sat and listened to the recordings.

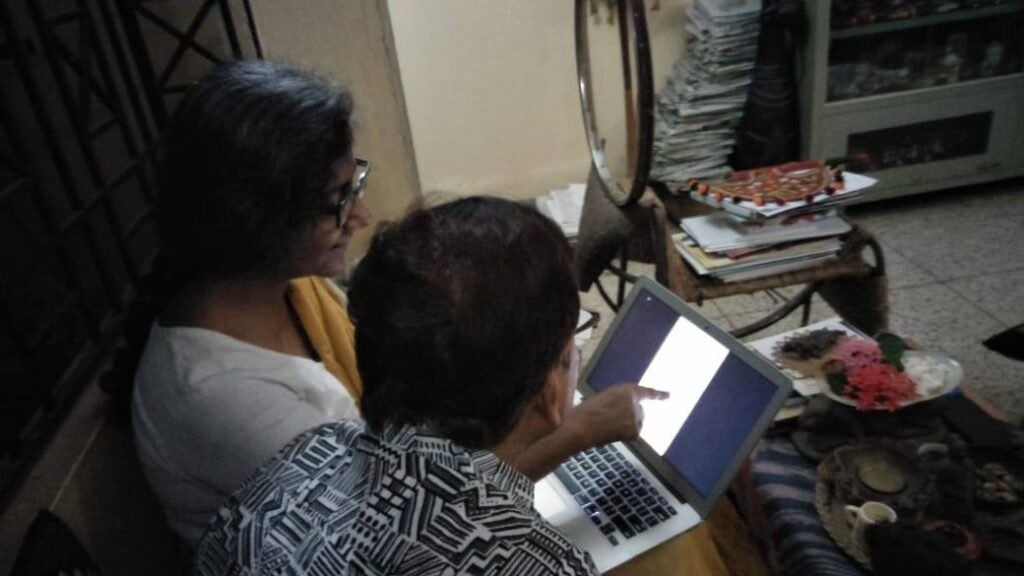

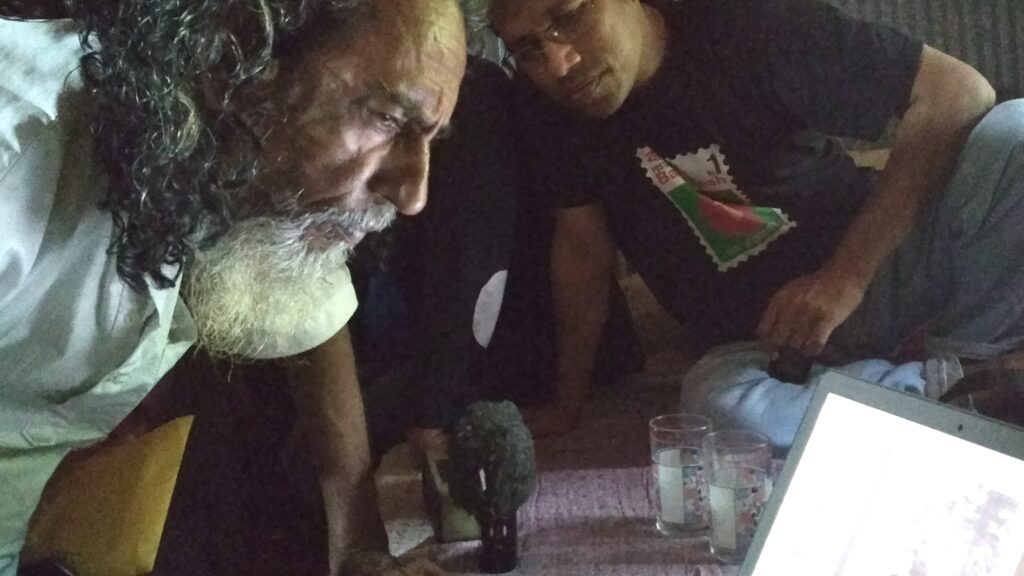

Listening with Subhomoy Roy and Charu Besra, from Kalapukur Danga village, near Santiniketan. 15 June 2018.

Subhomoy took some of Bake’s recordings to his teacher, Krishnapada Kisku, originally from west Midnapore district, who teaches Bangla in Albandha High School near Santiniketan. They listened together, and then his teacher sang him a song about the locomotive while Subhomoy wrote down the words. Then he sent both to me. But first what Kisku had to say about the Bonga song. He explained the words and showed how Bonga is not really shown in a positive light in the song. The second audio is the railgari song.

There was an image with Soumitra’s Facebook post, the one about Hul and his headmaster and Harma’s Village. He had got this photograph from his teacher, Arun Chowdhury’s collection. It shows the field of Bhagna Dihi, the village which gave us the leaders of the Santal rebellion of 1855-56, Sidhu, Kanhu, Chand and Bhairab It was taken in 1971. As I listened to Krishnapada Kisku’s locomotive song, I thought I could hear it cutting across this photograph—the sound and image inscribing a text on each other’s bodies, taking us from the past to the future and back.

This is where this sub-chapter would end, except that such things can go on forever. I am grateful to Soumitra Sankar Sengupta and Kumar Rana for allowing me to keep here their introduction to their Bangla anthology of Bodding’s folktales collection. I have drawn such inspiration from their writing that it feels selfish not to share it with others.

ভূমিকা

এক

সে অনেক দিন আগের কথা। সাঁওতাল পরগণাতে সাঁওতালদের বসত গড়ার প্রায় একশ বছর কেটে গেছে। লোকে বলে, সাঁওতালরা এসেছিলেন হাজারিবাগ অঞ্চল থেকে। মেলা কথা, এক দল সাঁওতালের বাস হল সাঁওতাল পরগণায়, অন্য দলের হল সিংভূম-পুরুলিয়া-বাঁকুড়া-ঝাড়গ্রাম-ময়ুরভঞ্জের বিরাট অঞ্চলে। কবে কখন কীভাবে হল তার সঠিক হদিশ আমরা জানি না, আর এখানে সে-সব কথার খোঁজও করা যাবে না। কেন না, এখানকার কথা শুরু হচ্ছে সাঁওতাল পরগণা থেকে। কিন্তু, লতায় পাতায়, কথা-কথালির হাত ধরে এখানকার সাঁওতালের সঙ্গে অন্য জায়গার, বহু দূর দেশের, উড়িষ্যা-আসাম-বাঁকুড়া-শিলদার সাঁওতালের যোগ তো থাকবেই। কথায় বলে এক মায়ের ছেলে-মেয়ে, যত দূরে দূরে থাক, ভাই ভাই থাকে, বোন বোন থাকে। তাদের কথাও কথাই থাকে।

তা সাঁওতালরা যখন এখানে আসেন, তখন এ অঞ্চলে পাহাড়িয়াদের বসবাস। তখনো সাঁওতাল পরগণা নাম হয়নি। নাম হল ১৮৫৫ সালে, সাঁওতালদের সেই বিরাট বিদ্রোহের পর। তখন এই অঞ্চলের নাম দামিন-ই-কোহ, যার মানে পাহাড়ের আঁচল। ফার্সিতে কোহ হল পাহাড়, আর দামন হল আঁচল। ইংরেজ কোম্পানি সাঁওতালদের কথা দিয়েছিল, এখানে এসে জমি-জায়গা তৈরি করে বসত গড়তে জমির খাজনা লাগবে না। সাঁওতাল পাহাড়-বন-টাঁড় কেটে জমি তৈরি করতে ওস্তাদ। দামিন-ই-কোহ জুড়ে গড়ে উঠল তাঁদের বসত। পাহাড়িয়াদের সঙ্গে ঝগড়া-ঝাঁটিও হল, কিন্তু আস্তে আস্তে সে সব মিটে গেল। তা করতে সেখানে এসে জুটল বাঙালি-বিহারি ব্যাপারি-মহাজনরা, সাঁওতালের ভাষায় দিকু। তারা ইংরেজের মদত পেল। ইংরেজ তাদের মদত পেল। সাঁওতালের জীবন হয়ে উঠল অতীষ্ঠ, ঋণ-কর্জায় বাঁধা পড়ল তার খেত। যে সাঁওতালের ঘর ভরে থাকত গরু-ছাগল-মুরগি-শুয়োর, যার ধানের মরাই সারা বছর ভরভরন্ত থাকত, যার ঘর ভর্তি বাঁশীর সুর, সাঁঝভর্তি বানাম-টামাক-তুমদার আওয়াজ, রাতভর্তি নাচ-গান-গল্প, শত শত বছর ধরে গড়ে তোলা ঘর-বংশ, ক-বছরের তফাতে সে হয়ে গেল দিনমজুর। তার জমি গেল, আবাদ গেল, খাবারের সংস্থান গেল। তাকে আষ্টেপৃষ্টে জড়িয়ে ধরল ঋণ-কর্জা। সেই অনাচারে দগ্ধ হয়ে সাঁওতাল বিদ্রোহ করল, সে-বিদ্রোহের নাম হুল। সে বিদ্রোহের কথা আমরা কম বেশি জানি। বছর বছর ৩০ জুন নানা লোক-বাক, সরকার-বেসরকার হুল দিবস মানায়। মনে করা হয় কেমন করে দুই বড় ভাই সিধু-কানু আর তাদের দুই ছোট ভাই চাঁদ-ভৈরবের সঙ্গে মিলে সাঁওতালরা লড়াইতে নেমেছিল। সে-সব কথার অনেক কিছুই কিন্তু কথা থেকে পাওয়া, লোকের মুখে মুখে ছড়িয়ে গিয়েছিল যে-সব কথা সেই সব কাহিনি থেকে। আবার অনেক কথা আমরা তেমনভাবে শুনতেও পাইনি। যেমন, সেই চার ভাইএর দুই বোন ফুলো-ঝানো আর তাদের সঙ্গে আরো আরো সাঁওতাল মেয়েদের সেই লড়াইতে যোগ দেবার কথা। সে-কথা থাক। আমরা আমাদের গল্পে ফিরে আসি।

সেই বিদ্রোহের বছর, ১৮৫৫ সালে, বীরভূমের একটা অংশ আর ভাগলপুরের একটা অংশ কেটে তৈরি হল সাঁওতাল পরগণা জেলা, সদর হল দুমকা। দুমকা নামটা এসেছে, লোকে তাই বলে, দামিন-ই-কোহ থেকে। এই দুমকাকে কেন্দ্র করে যেমন একদিন তার সর্বস্ব গেছিল, তেমনি একে কেন্দ্র করেই সংগৃহীত হয়ে উঠল সাঁওতালের প্রাণের ধনগুলো – তার ভাষা-কথা-গাছ-গাছড়া-ওষুধ-দৈনন্দিন চর্চা।

সেই দুমকা জেলায়, আজ থেকে একশ তিরিশ বছর আগে, ১৮৯০ খ্রিস্টাব্দের জানুয়ারি মাসে এসে পৌঁছলেন এক যুবক পাদ্রি। বয়েস মাত্র পঁচিশ বছর, নাম পল ওলাফ বোডিং, পি. ও. বোডিং নামে যাঁর খ্যাতি। তাঁর দেশ নরওয়ে। তাঁকে নিয়ে আসেন নরওয়ে দেশের আর এক মানুষ, লার্স ওলসেন স্ক্রেফস্রাড, এল ও স্ক্রেফস্রাড বলে লোকে তাঁকে জানে। স্ক্রেফস্রাড খুব কম বয়সে জেলে যান, জেল থেকে বেরিয়ে পাদ্রি হয়ে যান এবং ১৮৬৩ সালে গসনার মিশনের কাজে মাত্র তেইশ বছর বয়সে ভারতে আসেন। প্রথমে অধুনা পশ্চিমবাংলার পুরুলিয়াতে কিছুদিন থাকার পর যান রাঁচি, বর্তমান ঝাড়খণ্ড রাজ্যের সদর। ১৯০০ সালে এই রাঁচি শহরের জেলে মারা যান ব্রিটিশ রাজের বিরুদ্ধে মুণ্ডা বিদ্রোহের নেতা, ধারতি আবা, বিরসা মুণ্ডা। সে অন্য উপাখ্যান। শুধু এইটুকু বলে রাখা যায়, মুণ্ডা আর সাঁওতালের সম্পর্ক নিবিড়, বিশেষ ভাষার দিক দিয়ে। পুরোটাই মিলে মিল, ফারাক কম। স্ক্রেফস্রাড সেখানে কাটান চার বছর, ১৮৬৭তে তাঁর দিনেমার সহকর্মী হান্স পিটার বোরেসেন-এর সঙ্গে সাঁওতাল পরগণায় আসেন, সেখানে বর্তমান দুমকা জেলার বেনাগাড়িয়াতে এবেনেজার মিশন স্টেশন প্রতিষ্ঠা করেন। তাঁদের সঙ্গে ছিলেন ব্যাপটিস্ট মিশন সোসাইটির এক ইংরেজ পাদ্রি, নাম এডওয়ার্ড কল্পয়েস জনসন। খুবই সম্ভব যে, রাঁচিতে স্ক্রেফস্রার্ড মুণ্ডারি ভাষার সংস্পর্শে আসেন, যা তাঁকে সহজে সাঁওতালি ভাষার ভিতরবাড়িতে ঢুকে যেতে দেয়।

তা অনেক পাদ্রি তো এদেশে এসেছে, ইংরেজরাও এসেছে, তারা কি কখনো সাঁওতালদের মধ্যে কাজ করার কথা ভাবে নি? ভেবেছিল। যেমন উইলিয়াম কেরি সাহেবই তো ভেবেছিলেন। তিনি যখন মালদার মদনাবাটি থেকে দিনেমার উপনিবেশ শ্রীরামপুরে তখনই তিনি সাঁওতালদের ব্যাপারে খবর নিতে থাকেন। এমনকি তাঁর পাদ্রি বন্ধু উইলিয়াল ওয়ার্ডকে নিয়ে তিনি সাঁওতালদের দেশেও যান। সাঁওতালরা তাঁকে খুব টানে, কিন্তু নানা কারণে তাঁর সাঁওতালদের মধ্যে কাজ করার ইচ্ছা পূরণ হয়নি। সাঁওতালদের ঘনিষ্ঠ সংস্পর্শে আসা প্রথম পাদ্রি ছিলেন রেভারেন্ড এ. লেসলি। সে প্রায় দুশো বছর হতে চলল, ১৮২৪ সালে লেসলি ইংল্যান্ড থেকে ভারতে আসেন। তিন বছর কম কুড়ি বছর কাজ করেন রাজমহল পাহাড়ে সাঁওতালদের মধ্যে, তখনো সাঁওতাল হুল হতে অনেক দেরি। তা করতে লেসলি সাহেব খুব অসুখে পড়লেন, আর চারা না পেয়ে দেশে ফিরে গেলেন। এর তিরিশ বছরের ভিতর কোনো ইংরেজ পাদ্রি সাঁওতালদের মধ্যে কাজ করতে আসেননি। যতদিনে আসলেন, ততদিনে সাঁওতাল হুল হয়ে গেছে। কিছু ইংরাজ পাদ্রি এসে বীরভূমের সাঁওতালদের মধ্যে কাজ করতে শুরে করেন। সেটা ১৮৬৪-৬৫ সাল নাগাদ।

কিন্তু লেসলি সাহেব যখন রাজমহলে, তখন, ১৮৩৬ সালে আমেরিকার নিউ হ্যাম্পশায়ারের ফ্রি উইল ব্যাপ্টিস্ট ফরেন মিশন সোসাইটি এলি নয়েস ও জেরেমিয়া ফিলিপস নামের দুজন পাদ্রিকে কলকাতা পাঠায়। সেখান থেকে তাঁরা যান ওডিশা, করতে করতে তাঁরা সেখানে সাঁওতালদের সংস্পর্শে আসেন। চার বছর পর এলিকে ফিরে যেতে হয়, কিন্তু জেরেমিয়া থেকে যান। তিনি সাঁওতালি ভাষা শেখেন, আর ১৮৪৫ সালে সাঁওতালি ভাষায় একটি পুস্তিকা ছেপে বের করেন, এর লিপি ছিল বাংলা। এটাই হচ্ছে সাঁওতালি ভাষায় প্রথম কোনো ছাপা জিনিস। শুধু তাই নয়, ১৮৫২ সালে তিনি সাঁওতালি ভাষায় একটা ব্যাকরণও লেখেন।

মানে কথা, সাঁওতালদের ভাষা, সমাজ, আচার-বিচার নানা পাদ্রি, নানা বিদেশিকে টেনেছে। তাঁরা খ্রিস্টধর্ম প্রচার করতে এসেছিলেন ঠিকই, কিন্তু তাঁদের অনেকেরই প্রধান কাজ হয়ে দাঁড়াল এই মানুষদের জীবন নিয়ে লেখাপড়া করা, বিশ্বসংসারের কাছে এঁদের অমূল্য সম্পদ সাঁওতালি ভাষাকে তুলে ধরা। বোডিং নিজে মনে করতেন এ ভাষাভাষী লোকেরা এক সময় খুবই চিন্তাভাবনার কাজ করেছে, মাথার ঘাম যেমন পায়ে ফেলেছে, তেমনি মাথার ভিতর অনেক ঘাম ঝরিয়েছে। এমন এগিয়ে থাকা একটা ভাষার ভিতরঘরে কী আছে তা জানতে হবে না? দুনিয়ার লোক জানবে না, এমন একটা সম্পদের কথা? সাঁওতালি হোক বা সংস্কৃত, গ্রিক বা তামিল, এ সম্পদ তো মানুষের – পৃথিবীর সব লোকের। এভাবেই সাঁওতালি নিয়ে শুরু হল নানা চর্চা। এ কাজে সবচেয়ে এগিয়ে থাকা মানুষ স্ক্রেফস্রাড। প্রথম দশ বছর তাঁর সাঁওতালি শেখার সহায়ক ছিলেন খোদো। খোদো মারা যাওয়ার পর তিনি লিখেছিলেন: আমার মাস্টার খোদো বাড়ি ফিরে গেছে। সাঁওতালি ভাষায় মারা যাওয়া বোঝাতে নানা রূপকের ব্যবহার: বাড়ি ফিরে যাওয়া একটা, আবার, এগিয়ে যাওয়া আর একটা। এই পুরি থেকে ওই পুরিতে রওনা দেওয়া অন্য একটা। মানুষ রূপকে বেঁচে থাকে, তাই হয়তো মারা যাবার মতো একটা ঘটনাও ভাষায় প্রকাশ পেতে রূপকের আশ্রয় চায়। যাই হোক, এরপর একুশ বছর ধরে তাঁর সঙ্গে ছিলেন বিরাম হাঁসদা। যে কোনো ভাষার নিজস্বতা ফুটে ওঠে বাগধারাতে। সাঁওতালি ভাষার বাগধারাগুলো বিরাম যেমন জানতেন তেমন নাকি সাঁওতাল দুনিয়ায় কেউ জানতেন না। তাঁর কাছ থেকে মন দিয়ে সেইসব বাগধারা শিখেছিলেন বলেই স্ক্রেফস্রাডের ভাষা এত মিঠে।

তা করতে, স্ক্রেফস্রাডের নেতৃত্বে শুরু হল সাঁওতালি ভাষায় বাইবেলের তর্জমা, তার পর লেখা হল সাঁওতালি ব্যাকরণ। কিন্তু, তার আগেই স্ক্রেফস্রাড শুরু করেন এক বিরাট কাজ। তিনি খোঁজ পেলেন সাঁওতাল গুরু কলিয়ানের। সেই গুরু জানতেন সাঁওতালদের আদি কথা। কীভাবে পৃথিবী গড়ে উঠল, কীভাবে হাঁস-হাঁসিলের জন্ম, কীভাবে হাঁসিল দুটো সমান মাপের ডিম পাড়ল, আর সেখান থেকে জন্ম হল পিলচু হাড়াম আর পিলচি বুঢ়ির, আর তাদের থাকার জন্য ঠাকুর তৈরি করলেন এই পৃথিবী। তারপর সেই পিলচু হাড়াম আরে পিলচু বুঢ়ি থেকে এত লোক হল – এত বংশ হল। তারপর কোথায় সেই হিহিড়ি পিপিড়ি থেকে তারা এসে পৌঁছলো চাঁই চম্পাগড়, সেখান থেকে আবার মাদো সিং রাজার সঙ্গে ঝগড়া, আর সিংদুয়ার, বাহিদুয়ার ভেঙে সাঁওতালরা চলে এল এইদিকে। এই সব কাহিনি, যা জন্ম জন্ম ধরে সাঁওতালরা ছাটিয়ার বিন্তি হিসেবে বলে এসেছে, এক জন্ম থেকে আরেক জন্মে মনে রেখেছে, সেই সব কথা গুরু কলিয়ানের চেয়ে ভাল কেউ জানত না। তা স্ক্রেফস্রাড সাহেব সেই গুরুর চেলা হলেন। চেলা না হলে শিখবেন কী করে? সাদা চামড়ার পাদ্রি তাই শিষ্যত্ব নিলেন কালো চামড়ার গুরুর। তাঁর গুরুভাই হলেন জুগিয়া হাড়াম। গুরু কলিয়ানের কাছ থেকে সেই সব কাহিনি শুনে শুনে স্রেফস্রাড লিখে রাখতে লাগলেন। সাঁওতালদের ইতিহাস, সমাজ, সংস্কৃতি নিয়ে একটা খনি হয়ে রইল সেই লেখা। ১৮৭১ সালের ১৫ ফেব্রুয়ারি কলিয়ান গুরুর কথা শেষ হল, আর ১৮৮৭ সালে সাঁওতালি ভাষায় বই হিসেবে বেরলো সেই কথা: হড়কোরেন মারে হাপড়ামকো রেয়া কাথা (সাঁওতালদের পুরনো বুড়োদের কথা)। অনেক পরে বোডিং এর ইংরেজি তর্জমা করেন। কিন্তু এই ইংরেজি তর্জমা প্রকাশিত হয় বোডিংএর মৃত্যুর ছ-বছর পর, স্টেন কোনো-র সম্পাদনায়, ট্র্যাডিশনস অ্যান্ড ইন্সটিটিউশনস অব দ্য সান্তালস নামে। ১৯৫১ সালের জনগণনার সময় অশোক মিত্র-র অনুরোধে এই বইয়ের বাংলা তর্জমা করেছিলেন বৈদ্যনাথ হাঁসদা। সেটা বাঁকুড়া জেলার জনগণনার হাতড়াতে ছাপা হয়।

কলিয়ান গুরু একজন লোক বটে, কিন্তু তিনি আবার গুরু, মানে অনেক লোক, আর সকলের জ্ঞান, তাঁর ভিতর ঢুকে আছে। কলিয়ান গুরু যে কথাগুলো স্ক্রেফস্রাড আর জুগিয়া হাড়ামকে শোনালেন সে তো আর শুধু তাঁর একার কথা নয় – সব সাঁওতালের কথা। সেই হিহিড়ি পিপিড়ি, কঁয়ডা, কান্দাহারি, চাঁই চম্পাগড় – যেখানে যেখানে ছিল তার ঘর, সেখানে সেখানে সেখানে সে জমা করেছে কথা। সেই হল তার আদি কাহিনি। কিন্তু আদি কাহিনির সঙ্গে সঙ্গে চলতে থাকে তার প্রতিদিনকার কথা। আজ যে সাঁওতাল পরগণায় তার বাস, কিম্বা ওডিশায়, কিম্বা, ঝাড়গ্রাম-সিংভূম-মানবাজার-খাতড়া-হিড়বাঁধ- কোকড়াঝাড়-রাজশাহী-নাটোর – যেখানে যেখানে সে থাকছে, সেই সেই গাঁ-দেশ-লোক-গাছ-পাখি-পশু, সে-সব জায়গার ভাল-মন্দ, হাকিম-হুকুম, সব এসে তার কথায় জমা হয়। হাঁটতে হাঁটতে কথা, কাজের ফাঁকে জিরিয়ে নিতে নিতে কথা, গরু-ছাগল চরাতে চরাতে কথা, শীতের রাতে আগুন পোয়াতে পোয়াতে কথা – কথার শেষ নেই। সে কথার কতক হল যা যা চোখে দেখা যায়, যা যা হাতে ছোঁয়া যায়, আর কতক হল যা খালিচোখে দেখা যায় না, খালিহাতে ছোঁয়া যায় না – তাকে দেখতে হয় মনের চোখ দিয়ে, তাকে ধরতে হয় মনের হাত দিয়ে। আর এক কথা। সাঁওতালের মন উদার। ভাষা বিষয়ে তো বটেই। যেখানে সে মনের মতো, কাজে লাগার মতো শব্দ পেয়েছে, আদর করে তাকে নিজের ঘরে বসিয়েছে, ছুতমার্গ করেনি। তাই তো এ ভাষা এতো বিশাল – কত দিন-দুনিয়ার শব্দ তার ভিতর ঢুকে আছে। আবার উল্টোদিকে দিন-দুনিয়ার নানা ভাষায় কত শত সাঁওতাল শব্দ ঢুকে আছে।

বোডিং কুড়োতে লাগলেন সেইসব কথা। তিনি পাদ্রিও বটে আবার নানা বিষয়ে পণ্ডিতও বটে। তিনি স্ক্রেফস্রাডের সঙ্গে যোগ দেওয়াতে সাঁওতালি ভাষা নিয়ে চর্চা অনেক বেড়ে গেল। স্ক্রেফস্রাড শুরু করেছিলেন সাঁওতালি শব্দ কুড়ানোর কাজ, কয়েক হাজার শব্দ তিনি জোগাড়ও করেন। কিন্তু তাঁর অনেক কাজ, পেরে উঠছিলেন না, বোডিংকে দায়িত্ব দিলেন সাঁওতালি ভাষার একটা অভিধান তৈরি করার। কাজ শুরু হল বটে, কিন্তু শেষ হতে লেগে গেল বহু দিন। অভিধান তৈরি করা তো আর সোজা কাজ নয়, তার ওপর বোডিং-এর তেমন দলবল ছিল না। দল বলতে স্থানীয় সাঁওতালরা, যাঁদের কাছ থেকে তিনি শব্দগুলো জোগাড় করতেন এবং শিখতেন কীভাবে সেগুলোর ব্যবহার হচ্ছে। সেই করতে পাঁচ খণ্ডে সংগৃহীত হল সাঁওতালি অভিধান। প্রথম খণ্ড বেরলো ১৯৩২ সালে, স্ক্রেফস্রাডের মৃত্যুর বারো বছর পর। আর পঞ্চম ও শেষ খণ্ডটি বেরোতে লেগে গেল আরো চার বছর, ১৯৩৬ পর্যন্ত। তার ঠিক দু বছর আগে বোডিং ফিরে যান, কিন্তু নরওয়েতে না থেকে ডেনমার্কে বাসা বাঁধেন। তাঁর নিজের অনেকটাই তিনি রেখে যান সাঁওতাল পরগণায়, হয়তো তাই, কিম্বা অন্য কোনো কারণে তা আমরা জানি না, বোডিং তারপর আর মাত্র দু-বছর এ পৃথিবীতে থাকেন, ১৯৩৮ সালে পৃথিবী ছেড়ে অন্য জগতের দিকে এগিয়ে যান।

দুই

কথায় বলে কথা শব্দ একা থাকতে পারে না, তার সঙ্গী চাই। এই যেমন রাতের ঝিঁঝির ডাক। যেই নিশুত হল, ওমনি ঝিঁঝি রাতের শব্দ পেল। কোথাও কোনো শব্দ নেই, সেই নেই-শব্দটাই ঝিঁঝি শুনতে পায়। আর শুনে ডাক দেয়, রিঁ রিঁ রিঁ। একটার সঙ্গে আর একটা, তার সঙ্গে আর একটা, এই চলছে। কিম্বা ঘোর বর্ষার সময়, যেই মেঘের হুড়হুড় ডাকের আওয়াজ হল, জলের খলখল শব্দ হল, ওমনি সেই শব্দের ডাকে ব্যাং ডেকে উঠল। এক ব্যাং ডাকল তো আর এক ডাকল। ঝিঁঝি ডাকতে ডাকতে থকে গেল, এদিকে সূর্য আড়মোড়া ভাঙতে লাগল, আর মেঘের সঙ্গে তার হাতপায়ের ঘষা লেগে রাত ভেঙে দিন গড়ার শব্দ হতে লাগল, সেই শব্দের সঙ্গে মিলিয়ে জুলিয়ে ডেকে উঠল মোরগ – ছিড়কা মোরগ, কালো মোরগ, লাল মোরগ, শাদা মোরগ। শব্দে শব্দে তৈরি হতে লাগল কথা।

যেমন নাকি মহুয়া কুড়োতে গিয়ে লোকে পাতা তুলে আনে, দাঁতন ভেঙে আনে, তেমনি শব্দ খুঁজতে খুঁজতে বোডিং পেয়ে গেলেন অনেক কথা। আলাদা আলাদা কথা। আর শব্দ খোঁজার পাশাপাশি তিনি কুড়িয়ে বাড়িয়ে রাখতে লাগলেন সাঁওতালদের সেই সব কথা। আর কী সৌভাগ্য তাঁর, এবং আমাদের, এবং এ পৃথিবীতে যারা যারা মানুষের কথা শুনতে চায় তাদের সবার – তিনি পেয়ে গেলেন এমন এক সহকারী যিনি শুধু গল্প বলতেই জানতেন না, সেগুলো লিখেও রাখতে পারতেন। তাঁর নাম সাগ্রাম মুর্মু। সাগ্রামের মতো গল্প বলার গোপী কেউ ছিল না, তিনি অনেক গল্প জানতেন, আর সেগুলো বলে লোকেদের মাতিয়ে রাখতেন।

সাগ্রামের বাড়ি ছিল এখনকার গোড্ডা জেলার কোনো গ্রামে, কাজের খোঁজে এসে মহুলপাহাড়িতে বোডিং-এর সঙ্গে দেখা। বোডিং তাঁকে কাজ দিলেন, যে গল্পগুলো তিনি জানেন সেগুলো লিখে রাখার কাজ, আর যেগুলো তিনি জানেন না, কিন্তু অন্যেরা জানে, তাদের কাছ থেকে সেগুলো শুনে এসে লিখে রাখা। বোডিং-এর সঙ্গে কাজ করতে করতে অনেক গল্প জড়ো করেছিলেন সাগ্রাম। সাগ্রাম বুড়ো হবার পর বোডিং লিখেছিলেন তাঁকে দেখে গল্প বলার বাহাদুর ছাড়া আর কিছুই মনে হয় না। আর বলেছিলেন সাগ্রাম যেভাবে গল্পগুলো বলতেন, সে ধরনটাই একেবারে আলাদা। তিনি মাঝে মাঝে গল্পের মধ্যে নীতিকথা ঢুকিয়ে দেন। কথার মাঝে অমন নীতিকথা গুঁজে দেওয়াটা ভাল হলে ভাল, খারাপ হলে খারাপ, তা নিয়ে আমরা কিছু জানি না। কিন্তু, বোডিং বলে গেছেন, সাগ্রাম গল্প বলতে বলতে নীতিকথাগুলো এমন ভাবে কাহিনীর ভাঁজে ভাঁজে ঢুকিয়ে দিতেন, যে গল্পের নেশা কেটে যেত না। আর খুব সহজেই বুঝে ফেলা যেত কোন গল্পটা সাগ্রামের বলা।

এই কাজে আরো অনেকে ছিলেন, যেমন, দুর্গা টুডু, মোহন হেম্ব্রম, ভুজু মুর্মু, কানহু মারাণ্ডি, সোমায় মুর্মু, কান্দনা সোরেন, হরি বেসরা, এস হাঁসদা, সুগরি হাড়াম, ফাগু, শাঁখি হাঁসদা, ধুনু মুর্মু আর সোনার কথা শোনা যায়। শাঁখি হাঁসদা, ধুনু মুর্মু আর সোনা ছিলেন মহিলা। বোডিং বলে গেছেন যে, সাগ্রামের স্ত্রীও বোডিং-এর জন্য অনেক কটি কথা লিখে রেখেছিলেন। গল্পের টানে বোডিং এমন মাতা মাতলেন যে, তাঁর অভিধান ছেপে বেরোবার আগেই সাতটা কম একশ গল্প তিনটে বই হয়ে বেরিয়ে গেল। ১৯২৫ সালে প্রথম খণ্ড, ১৯২৭ ও ১৯২৯-এ দ্বিতীয় এবং তৃতীয়। সে বই-এর বাঁদিকের পাতায় সাঁওতালি ভাষায় লেখা মূল গল্প, আর পাশের পাতায় বোডিং-এর করা ইংরেজি তর্জমা। আমরা আজ আপনাদের হাতে যে কথাগুলো তুলে দিচ্ছি, সেগুলো হুবহু এই গল্পগুলোই, শুধু ভাষাটা বাংলা।

যেমন মহুয়া কুড়োতে কুড়োতে ঝুড়ি ভরে ওঠে, আর একটা একটা মহুয়া মিলে এক ঝুড়ি হয়ে যায়, কেউ আর তাদের আলাদা করে হিসেব রাখে না, বলে এক ঝুড়ি মহুয়া, তেমনি আলাদা আলাদা গল্পগুলো শুনতে শুনতে কখন যেন সাঁওতালদের গল্প হয়ে উঠল। হয়তো তিনি জানতেন এরকম হয়, কিম্বা জানতেন না, সে কথা আমরা বলতে পারব না। কিন্তু হতে হতে তাই হয়ে গেল। হবার আগে অবশ্য তাঁর শোনা এবং লিখে রাখা গল্পগুলোর একটা ছোট ঝুড়ি ভরে রেখেছিলেন ইংরাজ রাজপুরুষ এবং বিদ্যান্বেষী সিসিল হেনরি বমপাস। বমপাস কাজ করেছিলেন মানভূম ও সিংভূমে, তাঁর নিজের সংগ্রহ করা কাহিনীও ছিল। এগুলো তিনি প্রকাশ করেন ১৯০৯ সালে। তার অনেক পরে আরও ছোট কয়েকটা ঝুড়ি বোডিং বেঁচে থাকতেই ছেপে বেরলো। কিন্তু তিনি যে অনেক ঝুড়ি ভরে গেছিলেন, সেগুলো এখনো জমা আছে নরওয়ের অসলো ইউনিভার্সিটিতে। সেই কবে, প্রায় পঞ্চাশ বছর আগে ১৯৭১-৭২ সালে সন্তোষ সরেন সে-সব পাণ্ডুলিপি – সাগ্রাম এবং অন্যেদের হাতে লেখা সেই সব জিনিস – দেখে এসে তৎকালীন কেন্দ্রীয় মন্ত্রী অমিয় কিস্কুকে বলেন কিছু একটা করতে। কিছু কাজ এগোয়, বেশ কিছু পাণ্ডূলিপি মাইক্রোফিল্ম করে নিয়ে আসা হয়। তুলে দেওয়া হয় কলকাতার এশিয়াটিক সোসাইটি, বিশ্বভারতী বিশ্ববিদ্যালয়, রাঁচি বিশ্ববিদ্যালয় এবং অ্যান্থ্রোপোলজিক্যাল সার্ভে অফ ইন্ডিয়ার হাতে। কিন্তু তার বেশি কিছু হয়নি। আমরা এখনো সাঁওতাল লোককথার সেইটুকুই পাই যেটুকু বোডিং বেঁচে থাকতে ছেপে বেরিয়েছিল – সেগুলোই বার বার ছাপা হচ্ছে। বোডিং, সাগ্রাম এবং তাঁদের সহযোগীরা যে বিরাট সংগ্রহ গড়ে তুলেছিলেন, সন্তোষ সরেন তার একটা তালিকা তৈরি করেছেন। তাতে দেখা যাচ্ছে পাণ্ডুলিপিগুলোর শিরোনামের সংখ্যাই দেড় হাজার, সব যে গল্প তা নয়, তার মধ্যে গানও আছে, অন্য কথাও আছে। নরওয়েজিয়ান পাদ্রি ও সাঁওতাল বিশেষজ্ঞ রেভারেন্ড জোহানেস গাউসদাল এই পাণ্ডুলিপিগুলো সম্পর্কে বলতেন, “নওয়া দ হড় হপনকোয়া মারাং উতার ধন কানা – এগুলো সাঁওতালের অতি বড় সম্পদ!”

শুধু কি সাঁওতালের? মানুষের এই কথাগুলো, আর আর ভারতবাসীরও কি সম্পদ নয়? পৃথিবীর অন্য মানুষেরও কি নয়? লোককথা কি কেবল গোষ্ঠীর ধন হতে পারে? মানুষ যবে থেকে কথা বলতে শিখেছে তবে থেকে কাহিনি তার সঙ্গী – ছবি আকারে, গান আকারে, গল্প আকারে। সেই কাহিনি, কতক পৃথিবীর নানা বস্তু, মানুষের চারপাশের মাটি-গাছ-পাথর-প্রাণী, আর কতক যা এ পৃথিবীর লোকে দেখতে পায় না, যেমন হাওয়াপুরী, যেমন মানুষ ধরে খাওয়া রাক্ষস-রাক্ষসী, যেমন পিঠে বসিয়ে নিমেষে ভিনদেশে উড়িয়ে নিয়ে যাওয়া ঘোড়া, এই সব মিলে মিশে সে তৈরি করে নতুন নতুন কথা। পুরনো কথার ওপর নতুন কথা জমে, নতুন রঙের পোঁচ পড়ে, নতুন মসলা জোড়ে, এক গাঁ থেকে আর এক গাঁয়ে যেতে গিয়ে কাহিনী বদলে যায়। কিন্তু আবার অনেক কাহিনীর ভিতর তার আদি কাণ্ডটা একইরকম থাকে, তাকে ঘিরে ডালপালা গজায়, ছায়া হয়, ছায়ার ফাঁক দিয়ে রোদ পড়ে।

যেমন, ধরা যাক, কথা বলা পাখির কথা। সে কি শুধু সাঁওতালের কল্পনা? একইরকম কাহিনি তাহলে আমরা দুনিয়া জুড়ে লোকেদের মুখ থেকে কী ভাবে শুনি? সাঁওতাল লোককথায় আমরা যে পাখির কথোপকথন শুনি তারই অন্য একটা ধরণ শুনি বাংলায় ব্যাঙ্গমা-ব্যাঙ্গমীর গল্পে, কান্নাড় গল্পে, মালয়ালাম বা রাজস্থানী কিংবা কাশ্মীরি কাহিনীতে। সেই রকম কথা শুনি নাইজেরিয়া, কোরিয়া, চিন, পেরু, আজারবাইজান বা জার্মানির লোকেদের মুখে। পাখি কি কথা কয়? কইলেও সে-কথা কি মানুষের মনের ভাবের সঙ্গে বদলা-বদলি করতে পারে? সে-কথা আমরা বলতে পারি না, কিন্তু পৃথিবী জুড়ে মানুষ তাই মেনে এসেছে – পাখির সঙ্গে, শিয়ালের সঙ্গে, ঘোড়া বা কচ্ছপের সঙ্গে, কেঁচো, হাতি, চিতাবাঘ, সাপ, খরগোশ – সবার সঙ্গে কথা বলা চলে। এমন কল্পনা করতে পারে বলেই সে কাঠবিড়ালি বা হনুমান নয়, ভালুক বা চড়ুইপাখি নয়। সে মানুষ – তার দেশ যেখানেই হোক না কেন। তাই বোধ হয় নানা দেশে নানা মানুষ যুগ যুগ ধরে যে-সব কথা ধরে রেখেছে বলতে বলতে আর শুনতে শুনতে সেগুলোই তো একটা ভাষা। বাংলা বা সাঁওতালি, কন্নড় বা কিনৌরি, ইংরেজি বা চিনা – যে ভাষাতেই সে-সব কথা বলা হোক সেগুলোর ভিতর ভিতর বইতে থাকে একটা ঝর্ণা। কত যুগ কত বংশ ধরে কত কত লোকে হাঁটতে হাঁটতে ক্লান্ত হয়ে সেই ঝর্ণার জলে দু-দণ্ড পা ডুবিয়ে, দু আঁজলা জল খেয়ে আবার চলবার শক্তি পেয়েছে। চলতে চলতে কেউ এগিয়ে গেল দেশ-পৃথিবীর সীমানা ছাড়িয়ে, তার জায়গা নিল তার পরের লোক। কিন্তু চলার বিরাম নেই। তাই তার কোনো এক দেশে, এক ভূগোলে আটকে থাকার উপায় নেই। তার দেশ চলতে থাকে।

দেশ মানুষ গড়েনি, মানুষই দেশ গড়েছে। গড়তে গড়তে সে কতক নিয়ম তৈরি করেছে, যার সঙ্গে তার ভাষা, গায়ের রঙ, খাদ্যাভ্যাস, বসবাস, কোনো কিছুরই সম্পর্ক নেই। যেমন ধরা যাক, ভাই-বোনে বিয়ে না হওয়া। যেমন আমরা শুনি, সেই যখন পিলচু-হাড়াম আর পিলচু বুঢ়ি – যারা ছিল ভাই-বোন, আর যাদের ‘খারাপ’ কাজ থেকে জন্ম নিল মানব জাতি – তখন থেকে ঠাকুরের নিষেধ ভাই-বোনে বিয়ে হবে না। তাই নিয়ে তৈরি হল কত কাহিনি। কিন্তু, সে কি কেবল সাঁওতালদের মধ্যে? তা-তো নয়। সাঁওতাল ভূমি থেকে কয়েক হাজার মাইল দূরে ভারতের আর এক প্রান্ত কন্নড় দেশে এ. কে. রামানুজম শুনছেন একই রকম কাহিনি। যাঁরা সে-কাহিনি বলছেন তাঁদের সঙ্গে সাঁওতালদের কোনোরকম সম্পর্কের চিহ্ন পাওয়া যায় না। তাহলে দুই ভিন্ন গোষ্ঠীর মানুষের মধ্যে পাওয়া কাহিনি প্রায় খাপে খাপে মিলে যায় কী করে? কে জানে, হয়তো, যে নীতিবোধ পিলচু হাড়াম ও পিলচু বুঢ়ির ছেলে-মেয়েরা সাঁওতাল দেশে মেনে চলেছে, একইরকম কোনো নীতিবোধ সেই কন্নড় দেশের বংশধারায় কথা হিসেবে বয়ে চলেছে।

আবার মানুষ বলেই সে জানতে চায়। সাঁওতাল হোক বা হুতু, টুটসি হোক বা মাওরি, সে নানা কিছু জানতে চায়। যেমন আমরা আমাদের এক সাঁওতাল মেয়ের মুখে শুনি, “আমাকে এই বর দাও যেন আমি জানতে পারি যে, মরার পর আমাদের জীবন কোথায় যায়, কোথা দিয়ে সে শরীর ছেড়ে যায়, নাক দিয়ে না মুখ দিয়ে, এখান থেকে বেরিয়ে সে কোথায় যায় – এই সব কিছু আমি যেন দেখতে পাই।” কিম্বা সেই সাঁওতাল ছেলেটা যে তার বাপের বকা খেয়ে জ্ঞানের খোঁজে বেরিয়ে পড়ল, আর জ্ঞান সে পেল এক চাষির কাছ থেকে।

লোকেদের বলা-শোনা গল্প শুধু কথা নয়, কেবল কল্পনাও নয়। এ কল্পনার পরতে পরতে মিশে আছে বুদ্ধি। বুদ্ধি কথাকে অন্য মাত্রা দেয়। ‘আমার বাবা গেছে বৃষ্টির সঙ্গে দেখা করতে’, কিম্বা, ‘আমি একটাকে দুটো করি’ – এরকম শুনতে আবোল-তাবোল কথাগুলোকে নিয়ে গল্প হয়ে ওঠে গাছ-গাছালির বন, সে বনে অর্ধেক আলো, অর্ধেক অন্ধকার। সে জন্যই তার এত মান। কেবল কথা হলে কে তার এঁজোর প্যাঁজোর শোনার জন্য বসে থাকত?

পৃথিবীর মাটি, ঘরের খড়-কুটো, আর মানুষের বুদ্ধি ও কল্পনা মিলে এইরকম কত কথা যে সারা পৃথিবীময় ছড়িয়ে আছে। সেগুলো আলাদা বটে আবার আলাদা নয়ও বটে। একটার সঙ্গে একটার ফারাক ততটুকু, যতটুকু সেই দুজন লোকের, যাদের বাড়ি এক গাঁয়ের কুলহির এ-পারে ও-পারে। সে ফারাক কখনোই মানুষ আর শিয়ালের ভেদ নয়।

এই করতে, এক জনের কথা আর একজন শুনতে শুনতে, কখন যেন নিজের করে নেয়। যেমন সাঁওতালের ঘরে বন্দুক থাকে না, কিন্তু অন্যদের থাকে, সেখান থেকে বন্দুকটা আসে না, কিন্তু তার কথাটা ঢুকে পড়ে সাঁওতালের কথায়। সাঁওতাল রাজার বিরাট লোকলস্কর সিপাইসামন্ত থাকত না, অন্য রাজার থাকত, সেই লোকলস্কর কথায় কথায় মিশে গেল সাঁওতাল রাজার গল্পে। তেমনি, বাংলা ভাষার গল্পে সাঁওতাল কথাও রক্তেমাংসে মিশে আছে। সে সব আমরা খুঁজতে যাব না, গেলে আমাদের এই কথা আর শেষ হবে না।

তিন

আমাদের এই কথা, মানে তিন খণ্ডে প্রকাশিত “সান্তাল ফোক টেলস”-এর কাহিনিগুলো বাংলা ভাষায় তর্জমা, শুরু হয় বছর তিনেক আগে। তার অনেক থেকেই আমরা সাঁওতাল সমাজ এবং বোডিং-এর কাজ সম্পর্কে খানিক খানিক জেনেছি। বোধ হয় জানা থেকে আরো জানার ইচ্ছা নিয়েই এই তর্জমার কাজ হাতে নেওয়া। কিম্বা অন্য কিছুও হতে পারে, সে আমরা ভাল বলতে পারব না। তবে কাজটা যে করা দরকার সেটা আমাদের খুব মনে হচ্ছিল। সাঁওতালের গল্প শুধু সাঁওতালের গল্প তো নয়, সে তো আমাদের সবার গল্প। কিন্তু ভারতের কপাল খারাপ, একদল খালি “আরো নেব, আরো নেব” করতে করতে আসল জিনিসটাই নেওয়ার বেলা ফাঁকিতে পড়ে গেল। সেটা হল জানবার নানা কথা। এমনকি বোডিং উৎসাহ করে সংগ্রহ না করে রাখলে আমরা এগুলোর হদিশই পেতাম না। ভাষা সম্পর্কেও একই কথা, স্কেফস্রাড আর বোডিং-এর আয়োজন ছাড়া সাঁওতালি ভাষাটা যে আমরা যাকে দেশ বলি, সেই ভারতের কত বড় সম্পদ তা জানও সহজ হত না।

কী ভাবেই বা হত? সাঁওতালের সঙ্গে অন্যেদের সম্পর্ক প্রধানত শোষণের। ফন্দি-ফিকিরের মোকাবেলা করতে না পারা সাঁওতাল তার জমি-জায়গা, গরু-বাছুর, এমনকি নিজের জন্মভিটাও হারিয়েছে। এমনকি সাঁওতালদের একটা অংশ আদিবাসী পরিচিতিও হারিয়েছে। যে রাজ্যগুলোতে সাঁওতালদের বাস তার মধ্যে ঝাড়খণ্ড, পশ্চিমবাংলা, ওডিশা, বিহার ও ত্রিপুরাতে সাঁওতালদের তফসিলি জনজাতি হিসেবে গণ্য করা হয়, কিন্তু আসামে হয় না। আসাম সরকার তাঁদের এই স্বীকৃতি দেয় নি। উল্টে ১৮৫৫-র বিদ্রোহের পর যে সাঁওতালদের সাঁওতাল পরগণা থেকে আসামে নিয়ে গিয়ে সেখানকার বনভূমি ও পতিত জমিকে চাষযোগ্য করিয়ে তোলা হল, যে সাঁওতাল সেখানকার চা-শিল্পের অন্যতম প্রধান মেহনতি, সেইখানেই গত শতাব্দীর শেষার্ধে দেখা গেল রাষ্ট্রের প্রত্যক্ষ মদতে কয়েক হাজার সাঁওতালের হত্যা।

অন্য রাজ্যগুলোতে যে তাঁদের অবস্থা খুব ভাল তা নয়। ভারতের জনগণনার হিসেবে, ২০১১ সালে দেশে ৬৫,৭০,৮০৭ সাঁওতালের বাস (ঝাড়খণ্ডে ২৭,৫৪,৭২৩; পশ্চিমবাংলায় ২৫,১২,৩৩১; ওডিশায় ৮,৯৪,৭৬৪; বিহারে ৪,০৬,০৭৬; ত্রিপুরাতে ২,৯১৩। যেহেতু আসামে তাঁরা তফসিলি জনজাতি হিসেবে গণ্য হন না, তাই জনগণনার হিসেবে আসামের সাঁওতালদের খোঁজ পাওয়া যায় না, কারণ, জনগণনা কেবল তফসিলি জাতি ও জনজাতিভুক্ত সম্প্রদায়গুলো সম্পর্কেই আলাদা আলাদা তথ্য দেয়। অবশ্য আসামের অল সান্তাল স্টুডেন্টস ইউনিয়ন নামক সংগঠন একটি হিসেব কষে সেখানে সাঁওতালদের সংখ্যা অনুমান করেছেন ১২ লক্ষ।)। যে জনগোষ্ঠীর আছে এত বিপুল শব্দভাণ্ডার, এবং যে ভাষা দেশের অষ্টম তফসিলের অন্তর্ভুক্ত, সেই জনগোষ্ঠীর লোকেদের মধ্যে, ২০১১ জনগণনা অনুযায়ী, ছয় বছরের উর্ধ্বে প্রায় অর্ধেক লোকই নিরক্ষর। এঁদের জীবিকা অর্জনের প্রধান উপায় মজুরি (পশ্চিমবাংলায় ও বিহারে খেতমজুরের শতাংশ যথাক্রমে ৬৩ ও ৭৩), এবং চাষবাস (ঝাড়খণ্ড ও ওড়িশাতে কৃষক পরিচয় দেওয়া লোকের শতাংশ যথাক্রমে ৪৩ ও ৩৭)। বলে রাখা দরকার চাষবাস থেকে সারা বছর গ্রাসাচ্ছাদন চলে এমন পরিবারের সংখ্যা নগণ্য, কিন্তু সাঁওতাল নিজের অতীতকে মনে রেখে নিজেকে চাষি ভাবতেই ভালবাসে।

অর্থাৎ কিনা, বোডিং-এর সময় সমাজ যেমন সাঁওতালের প্রতিকূল ছিল আজও তাই। সাঁওতালের সকাল থেকে রাত পর্যন্ত খেটে যাওয়া। অত খেটে পুরো ভাত জোটে না, তা না যদি খাটে তাহলে তো ফাঁক-ফুঁক। ভাতের জন্যই সাগ্রাম মুর্মু নিজেদের গল্পগুলো বোডিং-এর জন্য লিখে যান, বিনিময়ে পান দৈনিক মজুরি, গল্পের সংগ্রাহক হিসেবে সাগ্রামের নাম চলে গেল পাদটীকায়। তাঁর কথার ওপর তাঁর নিজের কোনো নাম রইল না। আজও সাঁওতালের পক্ষে নিজের কথা বলতে পারা সহজ নয়। সরকারিভাবে পরিচালিত স্কুল শিক্ষাব্যবস্থার দুরবস্থা, খাদ্য-বস্ত্রের সংকট, রাষ্ট্র ও শাসকীয় সমাজের কাছে নিজের প্রকৃতি-পরিবেশ হারানোর দুঃসহ ধারাবাহিকতার পাশাপাশি আছে রাজনৈতিক সমস্যার কারণে বুদ্ধিচর্চার সীমাবদ্ধতা। নানা রাজ্যে নানা সরকার। বাংলা, ওডিয়া, হিন্দি, অসমিয়া – নানা ভাষায় তাঁদের লেখাপড়া করতে হয়। সাঁওতালি স্বীকৃতি পেলেও লিপি নিয়ে এখনো ঐকমত্য গড়ে ওঠেনি, এবং এখনো তাঁদের ভিন্ন ভিন্ন রাজ্যে দেবনাগরি, বাংলা, ওডিয়া, রোমান, ইত্যাদি ভিন্ন ভিন্ন লিপিতে সাঁওতালি ভাষার চর্চা করতে হয়। দিনের পরে দিন চলে যায়। এক রাজ্যের সাঁওতাল অন্য রাজ্যের সাঁওতালকে কোন ভাষায় কোন লিপিতে চিঠি লিখবেন, সেই প্রশ্নের মীমাংসা হয় না। সাঁওতালের বলার জন্য কথা আছে অনেক।

বোডিং কর্তৃক সংগৃহীত কাহিনিগুলোর মাত্র সামান্য অংশই প্রকাশিত। তাও মাত্র একটি অঞ্চলের, এবং সেই সংগ্রহের কাজের একশ বছর পার হতে চলল। এর মধ্যে আরো কথা জমেছে। সাঁওতালরা, নানা সংকট কাটিয়ে নিজেদের মতো করে নিজেদের কথা বলবার চেষ্টা করছেন। সে কথা অন্যরা যত শোনে ততই ভারতের লাভ। তামিল পাখির গানে, ডোগরি পাখির কথা আর সাঁওতালি পাখির সুর মিলে যে অপূর্ব সঙ্গীত উঠে আসতে পারে ভারতবাসীর কাছে সেটা এক কল্পনার রূপে হাজির করতে হলেও অনেককে অনেক কিছু করতে হবে। আমাদের এই তর্জমার চেষ্টা তারই সামান্য একটা উদ্যোগমাত্র।

আমরা বর্তমান তর্জমার কাজটি করেছি কয়েক ধাপে। প্রথমে বোডিং মূল সাঁওতালির পাশে যে ইংরেজি তর্জমা করেছিলেন, তার তর্জমা। দ্বিতীয় ধাপে, সম্পাদনার পর্বে, সেগুলোকে মূল সাঁওতালির সঙ্গে মিলিয়ে দেখা এবং প্রয়োজনমতো সম্পাদনা করা। তৃতীয় ধাপ ছিল, তর্জমা করা বেশ কিছু গল্প কিছু সাঁওতাল ও কিছু বাংলাভাষী লোককে শোনানো। এটা ঠিক যে, একই মজার গল্প সাঁওতালরা শুনে যতটা মজা পেয়েছেন, সব বাংলাভাষী কিন্তু ততটা পান নি। তাঁদের মন আর সাঁওতালের মন এক পরিবেশে গড়ে ওঠে নি। কিন্তু মানবমনের যে মূল, যার ভেতর দিয়ে মানুষ রস সংগ্রহ করে লতায় পাতায় বেড়ে ওঠে, সেই মূলের একটা সন্ধান গল্পগুলো পড়ে শোনাবার সময় আমরা পেতে লাগলাম। আমাদের বিশ্বাস, তর্জমার কাজটা যদি ভালভাবে করতে পারতাম তাহলে হয়তো এই মূলের গভীরতাটাও আরো বেশি করে তুলে আনা যেত।

আর একটা কথা না বললেই নয়। সাগ্রাম এবং তার সহযোগীদের বলা ও লেখা কথা তর্জমা করার সময় বোডিং পাদটীকায় কিছু কথা লিখে গেছেন। যে গল্পগুলো সাগ্রাম নিজে বলেন নি, অন্য কোন কথকের মুখে শুনে লিখেছেন, সেই সব গল্পের পাদটীকায় কথকের নাম আলাদা করে লিখে দিয়েছেন। কিন্তু আরো একটা ব্যাপার আছে। বোডিং তো তর্জমা করেছেন ইংরেজিতে। তার মানে তাঁর পাঠক ইংরেজি ভাষার। সে পাঠক বাংলা এবং সাঁওতালি ভাষা জানেন না, কারণ, এই কথাগুলো তাঁদের দেশে খুঁজে পাওয়া না। সেই পাঠকদের কাছে কাহিনিগুলোর ধারাটা কিছুটা সহজ করে দেওয়ার জন্য বোডিং পাদটীকার ব্যাখ্যাগুলো দিয়েছেন। তিনি এটাও জানতেন লোককথা কোন একটা অঞ্চলের নয়, সারা দুনিয়ার সব মানুষের। ইংরেজিতে তর্জমা করা মানে একটি অঞ্চল থেকে কথার ফুল-ফল সারা দুনিয়ার মানুষের কাছে পৌঁছে দেওয়া। তাই সেকালের বাংলা বিহার সীমান্ত অঞ্চলের, বীরভূম থেকে ভাগলপুর পর্যন্ত বিস্তীর্ণ সাঁওতালভূমির জীবনযাপনের খুঁটিনাটি, রীতিনীতি, ঘরদুয়ার, তৈজসপত্র সব কিছুই তিনি নিখুঁতভাবে পাদটীকায় লিখে গেছেন। কেমন হয় একটি সাঁওতাল গ্রামের বাড়ি, কীভাবে বিয়ের কথা পাকা হয়, কেনই বা ভাল শিয়াল সাঁওতালিতে কথা বলে আর চতুর বদমাস শিয়ালের মুখের ভাষা বাংলা, কেমন করে ঝুড়ি বোনা হয়, কীভাবে লাঙল বানানো হয়, আর সেই লাঙল চাষজমি তৈরির জন্য কীভাবে মাটির উপর দিয়ে টানা হয়, কেমন করে বাঁশের টুকরো কেটে বানিয়ে নেওয়া হয় তেল বয়ে নিয়ে যাওয়ার পাত্র – সে সব নিখুঁতভাবে লিখেছেন বোডিং। বাংলা বিহার থেকে দূর দেশে, ভারতের অন্য প্রান্তে, দুনিয়ার অন্য কোন শহরে বা গ্রামে বসে কেউ যখন বোডিং এর তর্জমা আর পাদটীকা পড়বেন তিনি চোখের সামনে দেখতে পাবেন উঁচু-নিচু কাঁকুরে পথে এক সাঁওতাল দম্পতির হেঁটে যাওয়া। একজনের মাথায় ঝুড়ি, অন্যজন বাপের বাড়ি থেকে ফেরার সময় উপহার পাওয়া একপাত্র তেল হাতে ঝুলিয়ে নিয়ে চলেছে।

কিন্তু আমরা তো তর্জমা করেছি বাংলা ভাষায়। এ বই যাঁরা পড়বেন, একটি দুটি বিষয় ছাড়া আর সবই তাঁদের চেনা জানা। তাই বোডিং এর পাদটীকার অল্প কয়েকটিই আমরা রেখেছি। কোথাও কোথাও দরকারমতো সেটাকে গল্পের সঙ্গেই জুড়ে দেওয়া হয়েছে। আমাদের বিশ্বাস এতে কোথাও গল্পের অঙ্গহানি হয় নি, গতিও আটকায় নি।

কাজটা করার ব্যাপারে কী উৎসাহই না পাওয়া গেছে! এশিয়াটিক সোসাইটির সঙ্গে যুক্ত বিভিন্ন বিদ্যাবেত্তা, বিশেষত সত্যব্রত চক্রবর্তী ও রামকৃষ্ণ চট্টোপাধায়ের আগ্রহ এ কাজের প্রধান প্রোৎসাহন। তর্জমার কাজে আমাদের সহকর্মী জয়া মিত্র ও প্রীতম মুখোপাধ্যায় কাজটা করতে এক কথায় রাজি হলেন, এবং যথাসময়ে তাঁদের ভাগের কাজটা শেষও করলেন বলে আমরা এতদূর পৌঁছতে পারলাম। সম্পাদনা বিষয়ে আমরা যেটুকু শিখতে পেরেছি তার বেশির ভাগটাই তরুণ পাইনের হাত ধরে। এই বইটি তর্জমা ও গ্রন্থনার কাজেও তাঁর উদার বিদ্যাচিন্তা আমাদের সহায় থেকেছে। গল্পগুলোর খসড়া তর্জমা শুনবার জন্য রানি মুর্মু, ভজন কিস্কু, দুলি হাঁসদা, রাবণ মার্ডি, বিশু মুর্মু ও ছবি টুডু আমাদের প্রচুর সময় দিয়েছেন, আপ্যায়নও করেছেন। তাঁরাও কার্যত এই কাজের সহযোগী। আর যাঁরা এর সহযোগী তাঁরা হলেন বড়ো বাস্কে, মেরুনা মুর্মু, অচিন চক্রবর্তী, অনির্বাণ চট্টোপাধায়, দিলীপ ঘোষ, উর্বা চৌধুরী ও সীমান্ত গুহঠাকুরতা। খসড়া তর্জমাগুলোর কিছু কিছু অংশ তাঁরা পড়ে দিয়েছেন। শুভ্র ভট্টাচার্য পাণ্ডুলিপি তৈরি করতে খুবই সাহায্য করেছেন। আরো অনেকে এঁর সঙ্গে নানা ভাবে যুক্ত থেকেছেন, তাঁদের সবার কথা বলা মুস্কিল। তাই আরো অনেক ত্রুটির সঙ্গে এই ভুলের জন্য মার্জনা চেয়ে নিচ্ছি।

লোকতত্ববিদ এ কে রামানুজন কর্ণাটকের এক গ্রামে শুনেছিলেন একটা গল্পের গল্প। এক নারী গল্প জানতেন, কিন্তু তিনি সেগুলোকে বাইরে বেরোতে দিতেন না। তা, গল্প তো বন্দী থাকার লোক নয়, তাই সবাই ঘুমোলে তারা বেরোতো, নিশুত রাতে। কোরিয়া দেশের এক কাহিনিতে শোনা যায় কীভাবে এক রাজপুত্র শোনা হয়ে গেলে গল্পগুলোকে একটা ঝোলাতে ভরে রেখে দিত। আর সেই রাগে তারা রাজপুত্রের ওপর শোধ নেবার কতরকম চেষ্টা করল! আমাদের এখানে, ঝাড়গ্রাম জেলায়, এক বৃদ্ধ সাঁওতাল থাকতেন। গল্প শোনানো তাঁর নেশা, কিন্তু কক্ষনো তিনি কোনো ঘরের ভিতর গল্প বলতেন না। বলতেন খোলা বারান্দায়, দাওয়ায়, কুলহির ধারে, কিম্বা মাঠে বা পুকুর ঘাটে। তাঁর কথা, ঘুরে বেড়ানোতেই গল্পের প্রাণ, আটকে থাকলেই তার মরণ। তাই গল্প বলতে হয় খোলা জায়গায়, যাতে তারা নিজের ইচ্ছামতো এদিক ওদিক, কে জানে কোন দিক, ছড়িয়ে যেতে পারে। বর্তমান তর্জমার কাজটাতেও চেষ্টা করা হয়েছে খোলা জায়গায় গল্পগুলোকে মেলে দিতে। কতটুকু পারা গেল, সে-কথা গল্পগুলোই পাঠককে বলে দেবে। এইটুকুই ছিল আমাদের কথা। সবাইকে জোহার – নমস্কার।

কুমার রাণা

সৌমিত্রশংকর সেনগুপ্ত

কলকাতা

আগস্ট ২০২০

From Rana, Kumar and Soumitra Sankar Sengupta ed., Santal Lokkatha: Paul Olaf Bodding-er Santal Folktales-er Bangla Tarjama (Kolkata: The Asiatic Society, 2022)

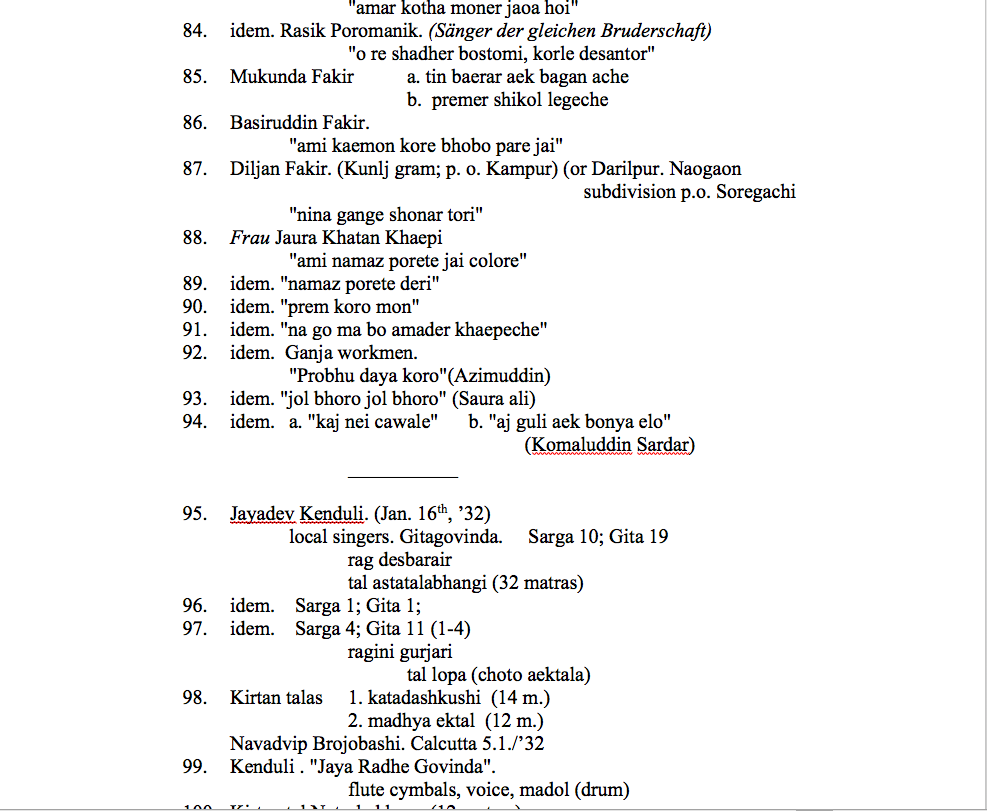

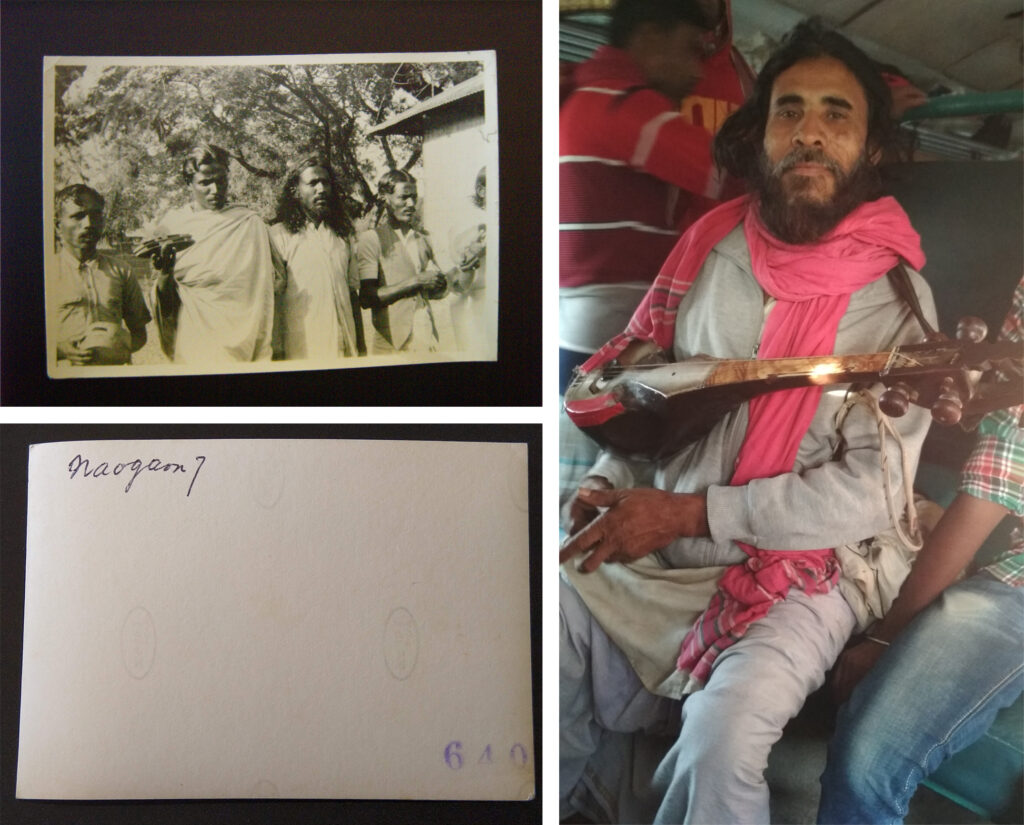

They were all insiders to the sound of Arnold Bake’s recordings from the Dumka Hills, yet they were all different too. The listening sessions in Kairabani, Harinsingha, Jamuasol and at Johar and NELC in Dumka in Dumka town, revealed a range of reception and interpretation of the sounds held in Bake’s Santal cylinders. The insider-listeners responded from their individual social, economic, historical and cultural locations, since any community is not one homogenous group but it is complex, fragmented and layered; an assemblage of multiple communities within a community.

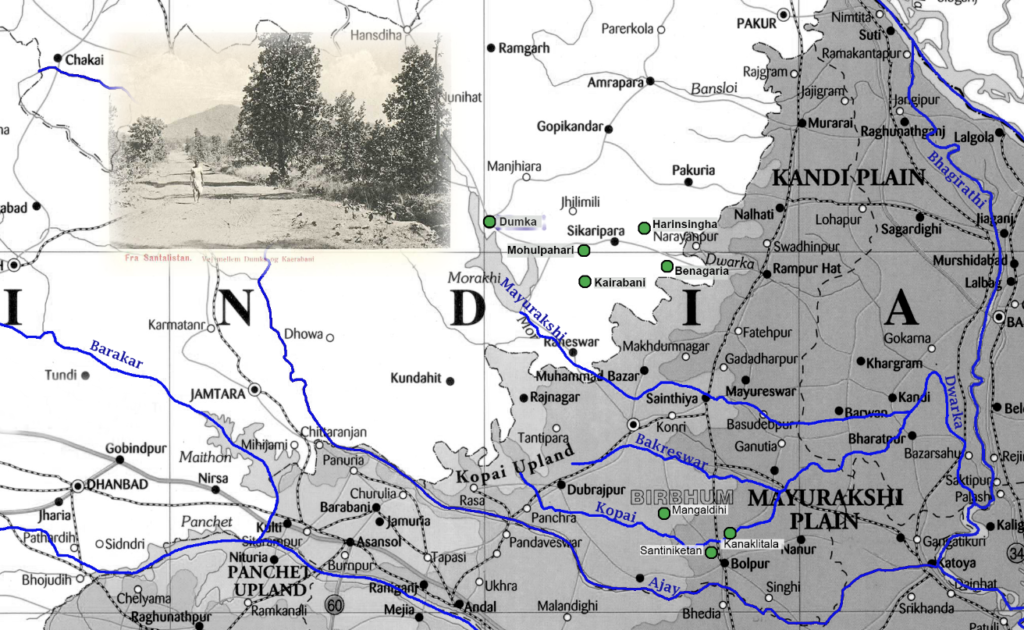

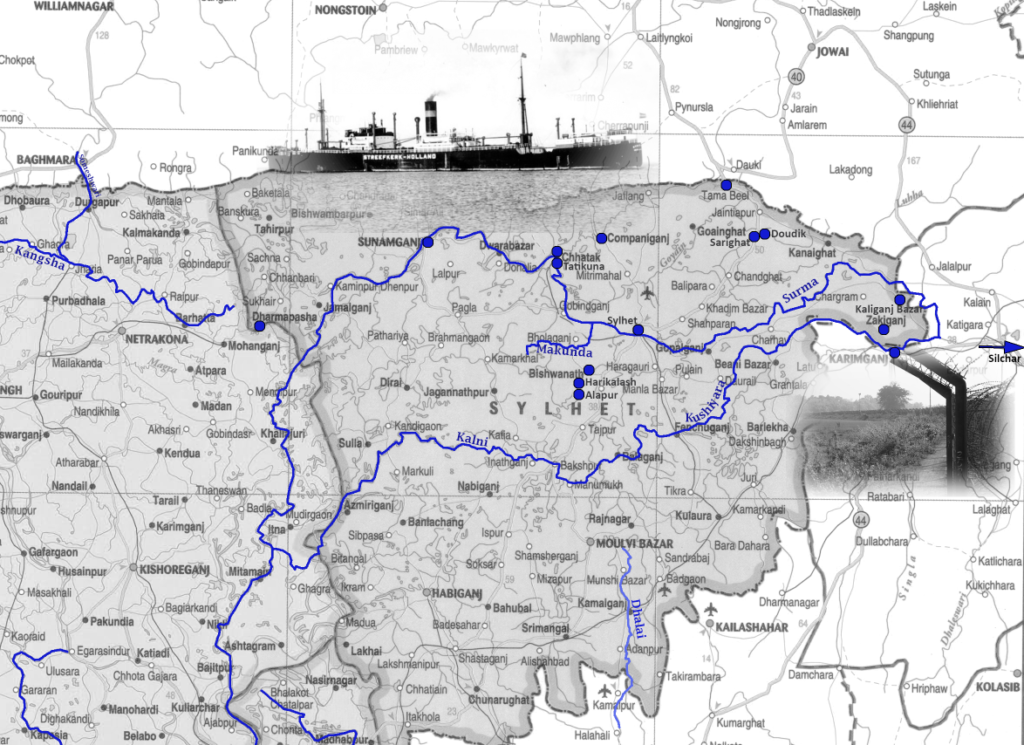

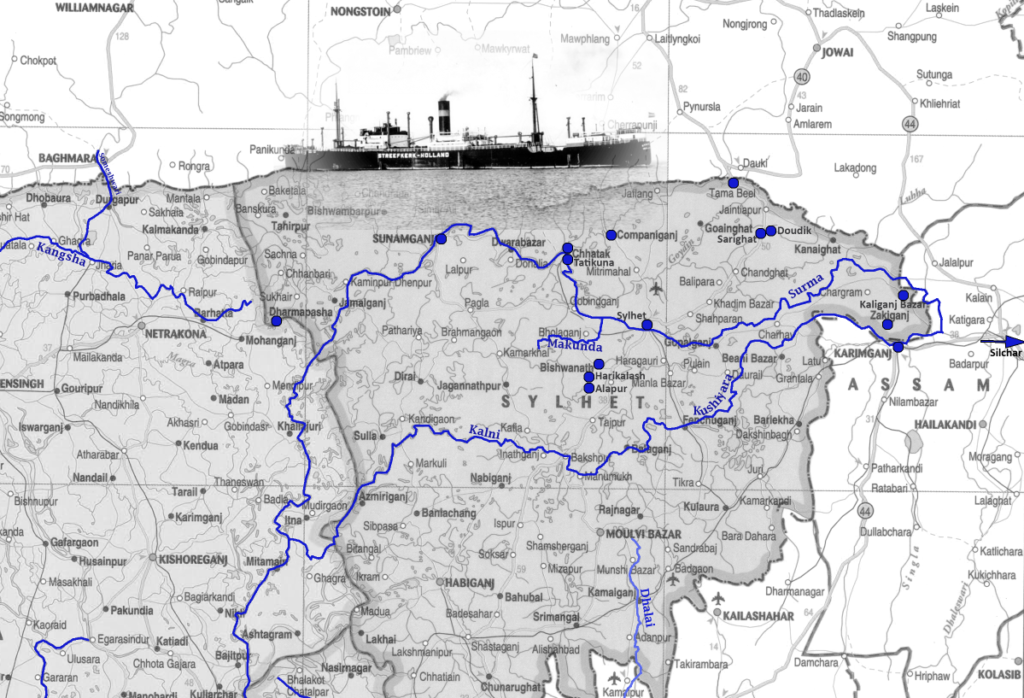

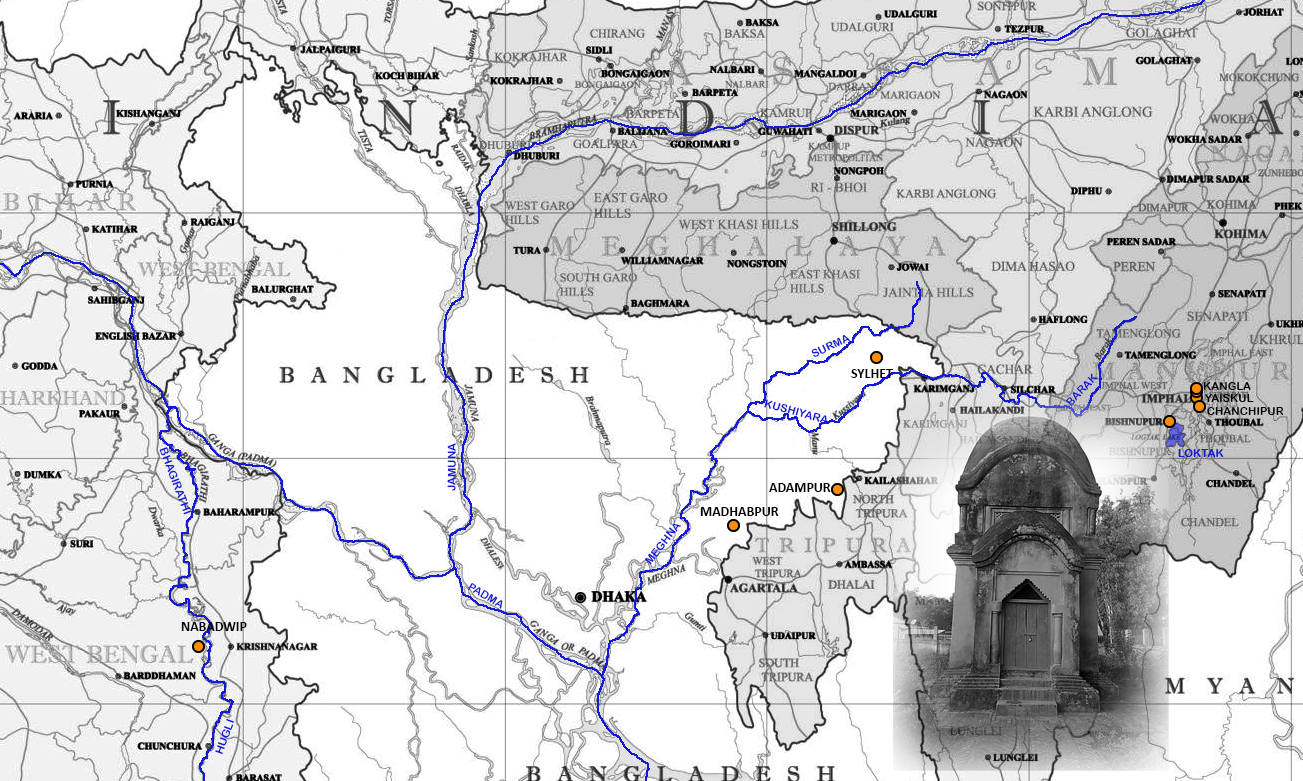

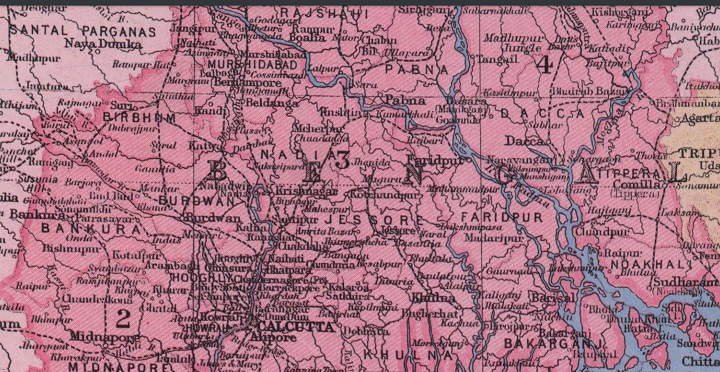

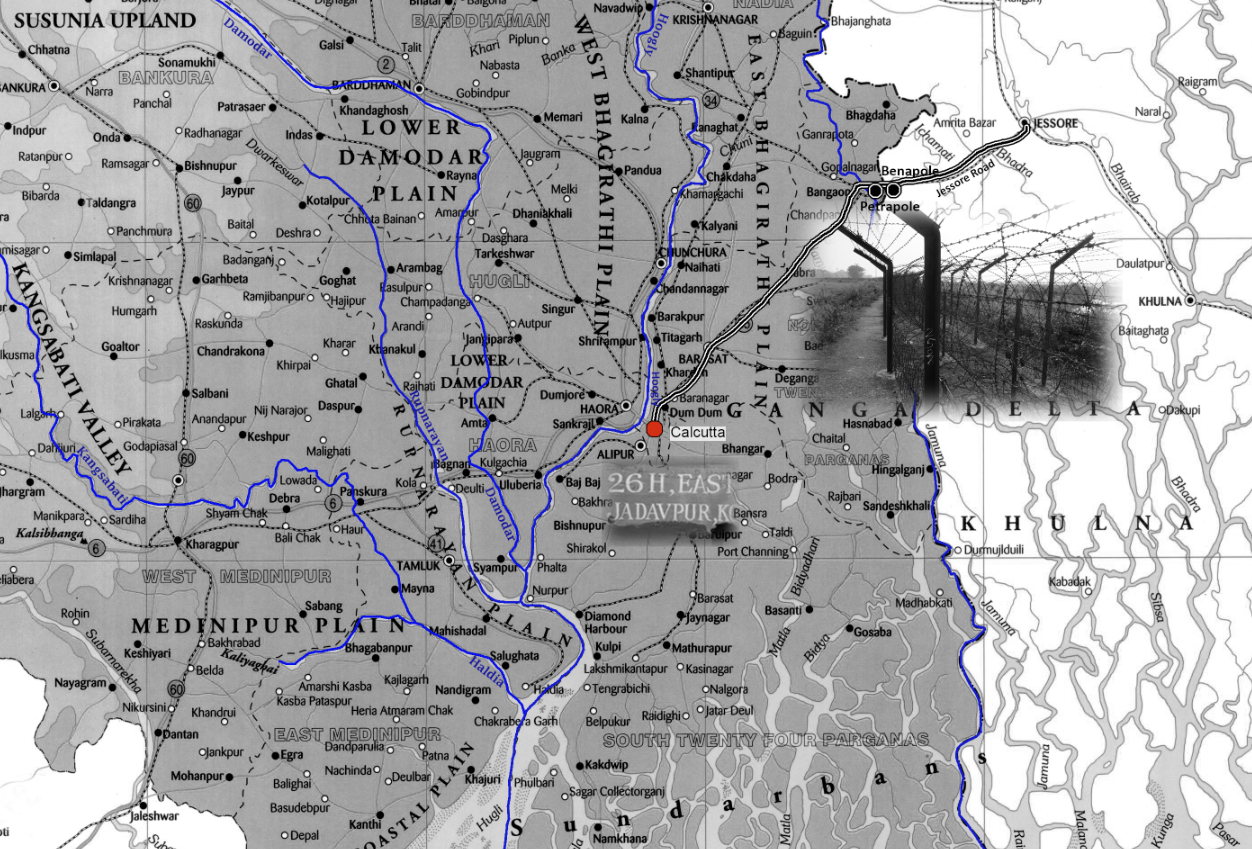

The Dumka Hills. Map designed by Purba Rudra, 2021.

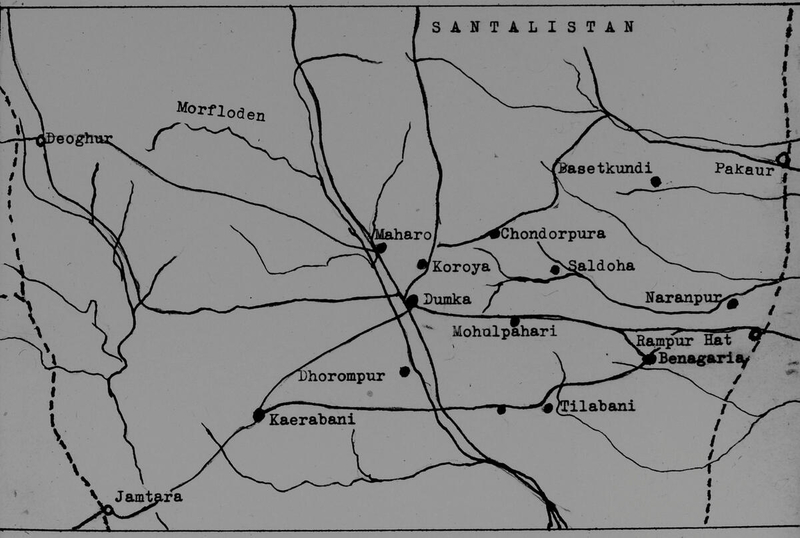

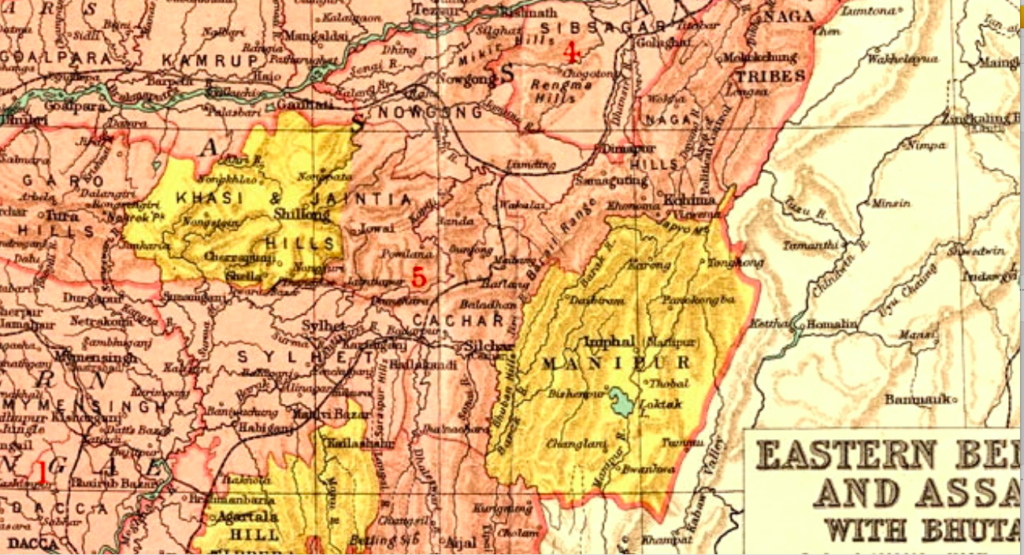

Old map of Santalistan, from the digital library of the University of South California. Source: Danmission Photo Archive. Rights: CC Attribution (CC BY). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Permanent link: http://doi.org/10.25549/impa-c123-104208

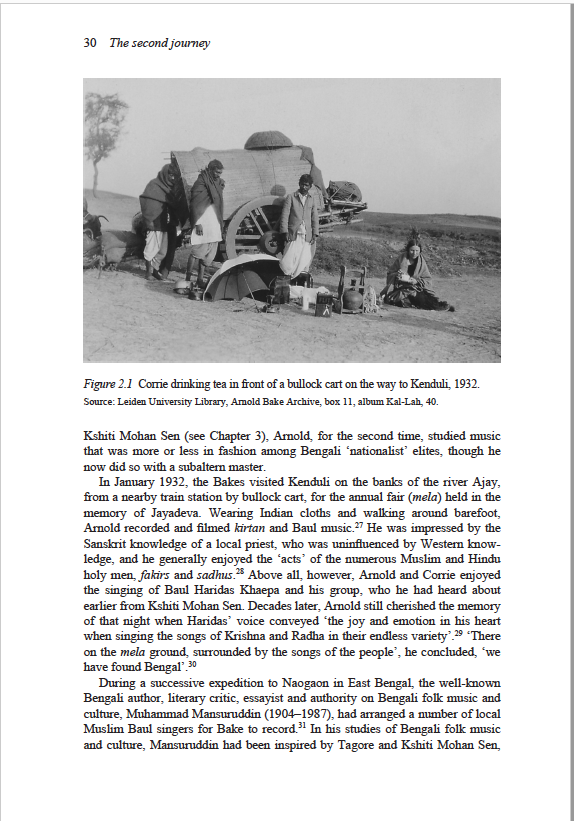

In 1931, within a couple of months after returning to India and settling back in Santiniketan, Bake had started to make preparations for going to the Dumka Hills in the Santal Parganas (now the state of Jharkhand). He got in touch with the Norwegian missionary and pioneer scholar of Santal Studies, Dr Paul Olaf Bodding (1865-1938), who was secretary of the Santal Mission of the Northern Churches and was stationed in Mohulpahari. Dr Bodding was not only a great scholar and linguist, but he was a collector of local knowledge and an archivist. His work can be seen as a living archive of the Santali language, grammar, folktales and folk medicine.

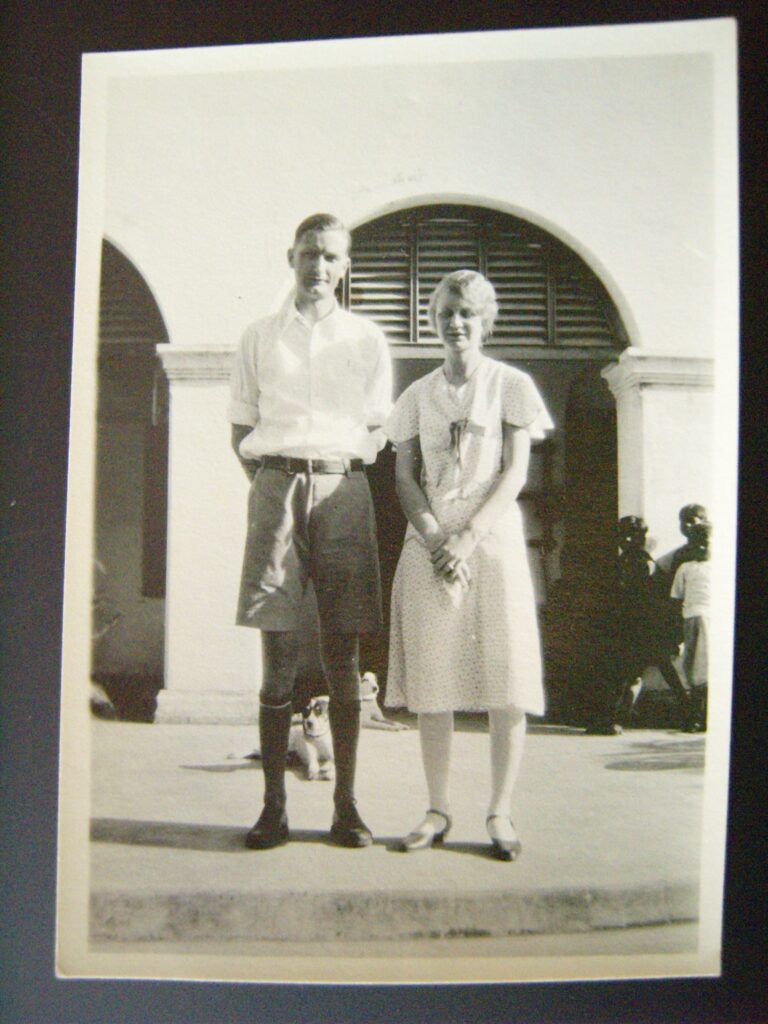

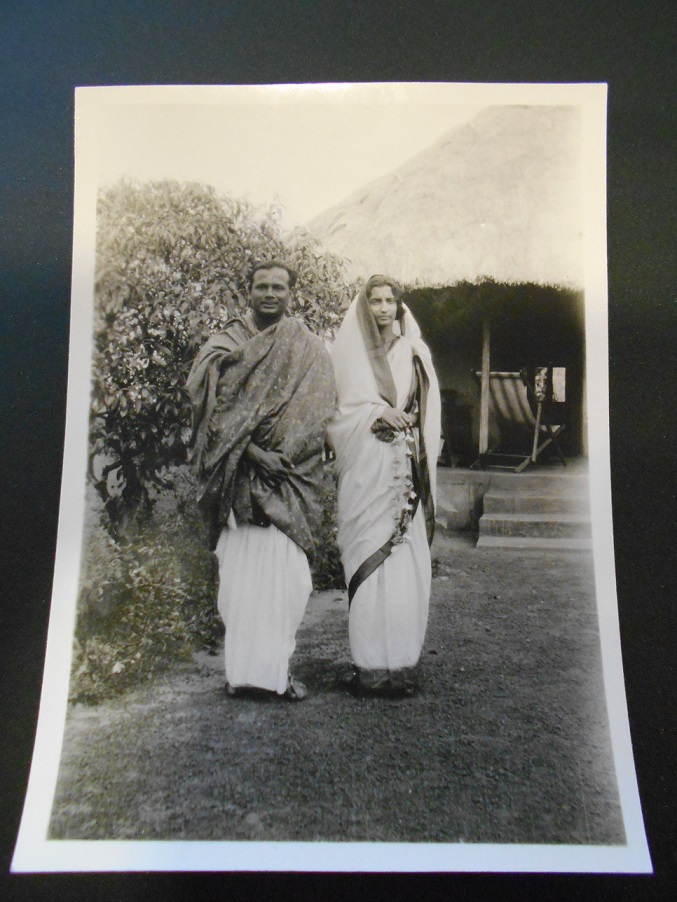

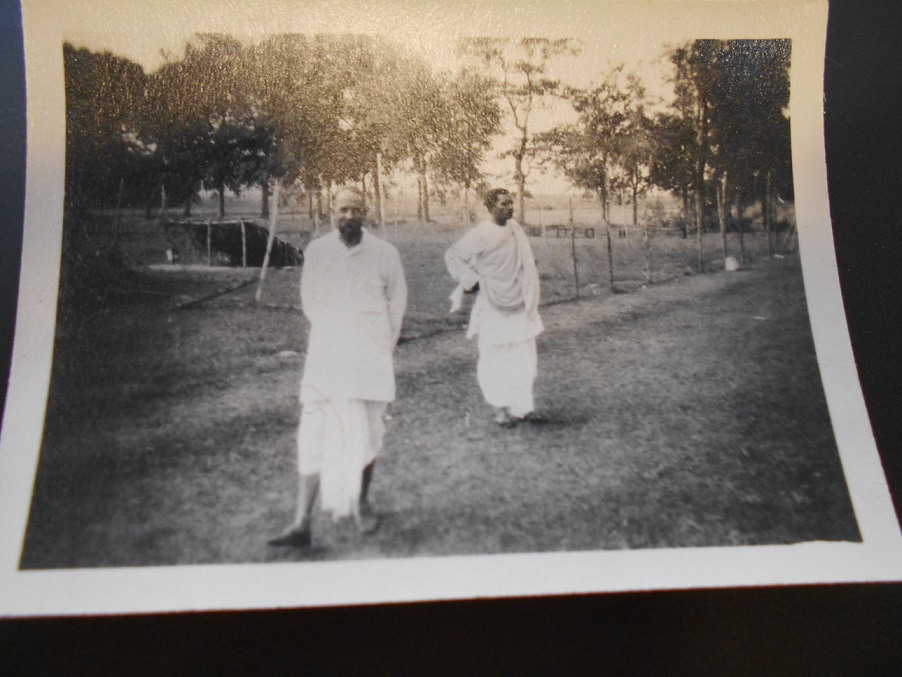

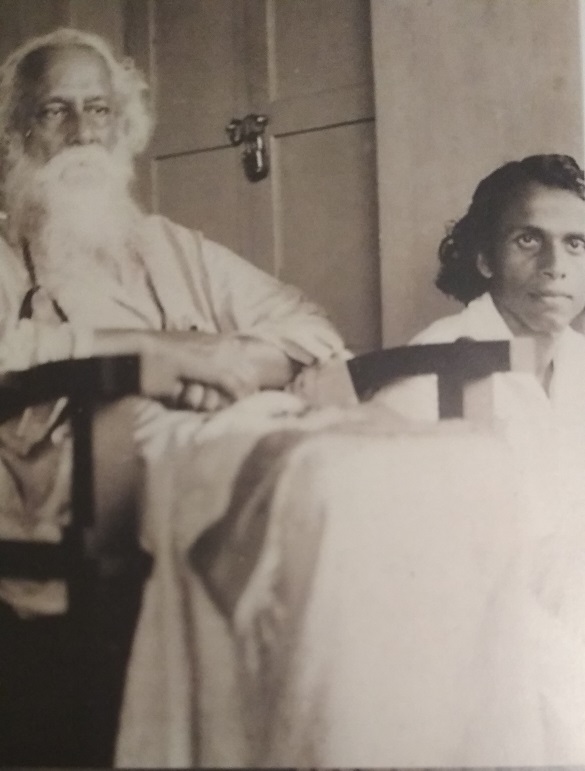

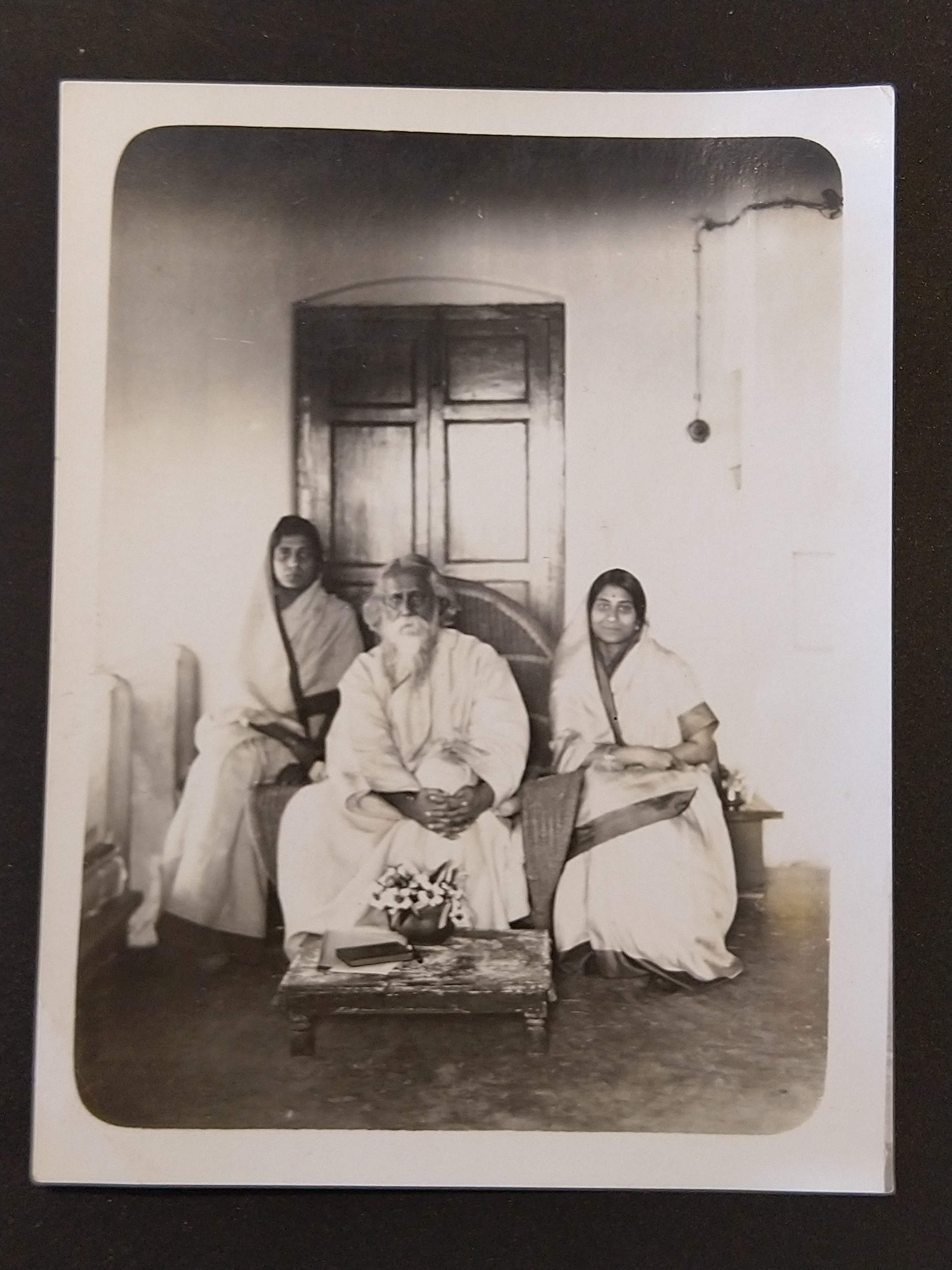

This photograph, of Dr Paul Olaf Bodding and his wife Christine, was taken in Darjeeling in 1930. Therefore, this is how Dr Bodding would have looked when Arnold Bake met him. It’s source is the digital library of the University of South California. The Danmission Photo Archive. Rights: CC Attribution (CC BY). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Permanent link: http://doi.org/10.25549/impa-c123-98677

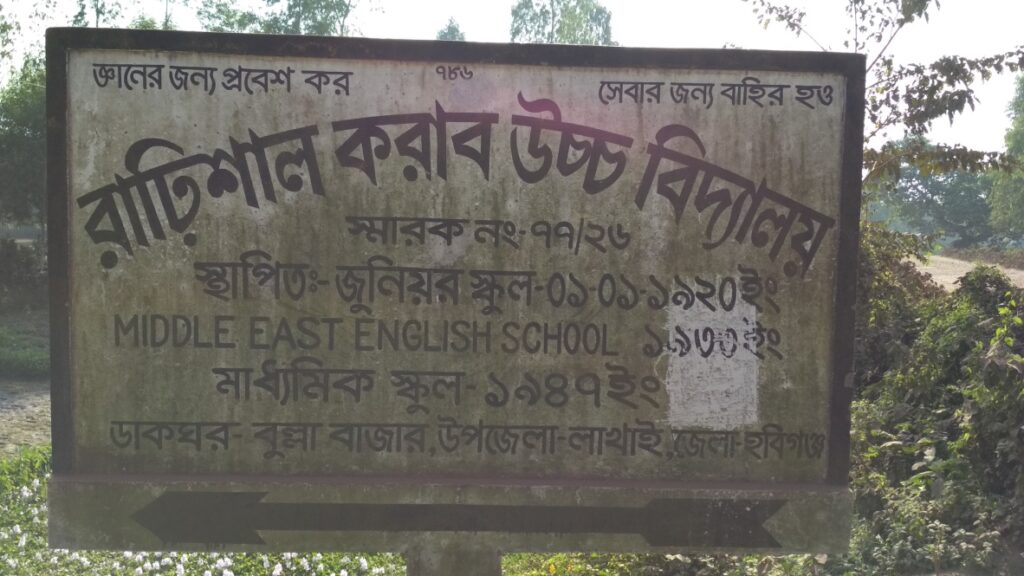

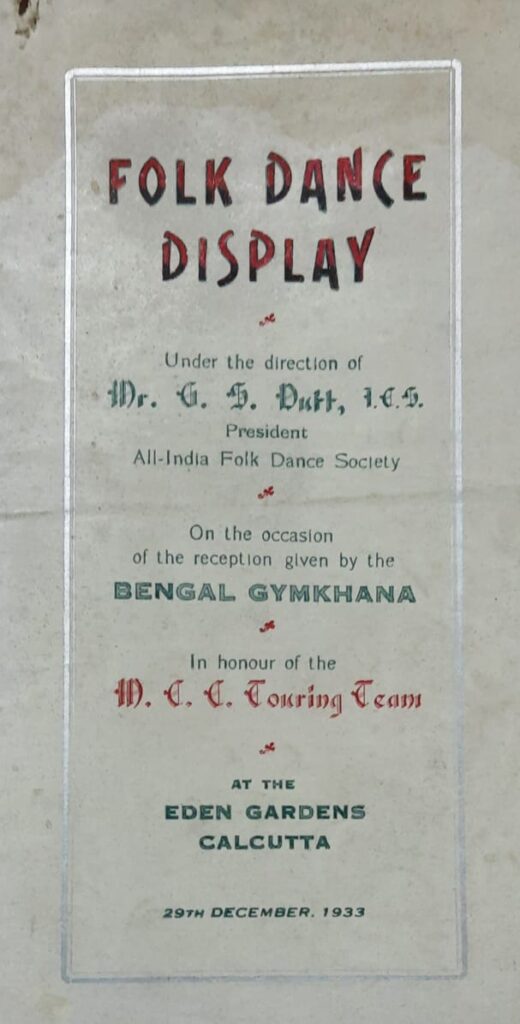

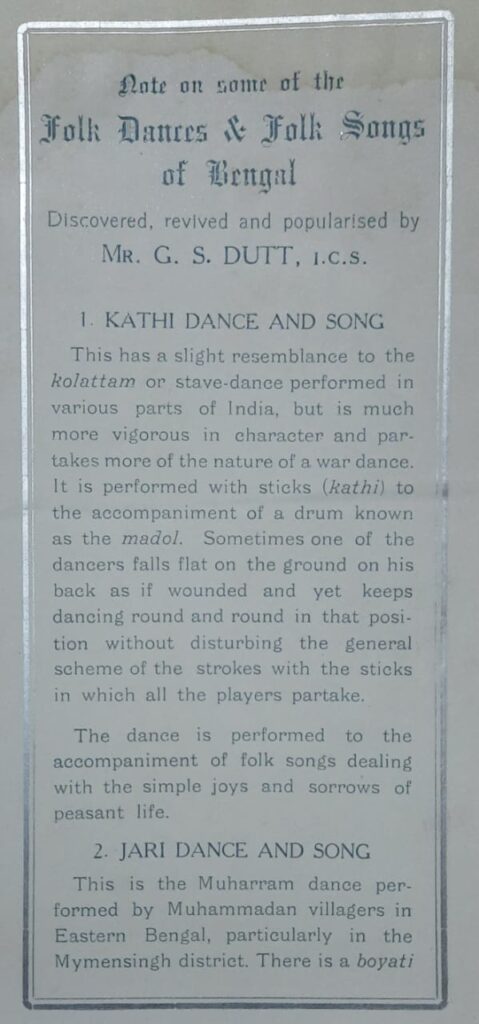

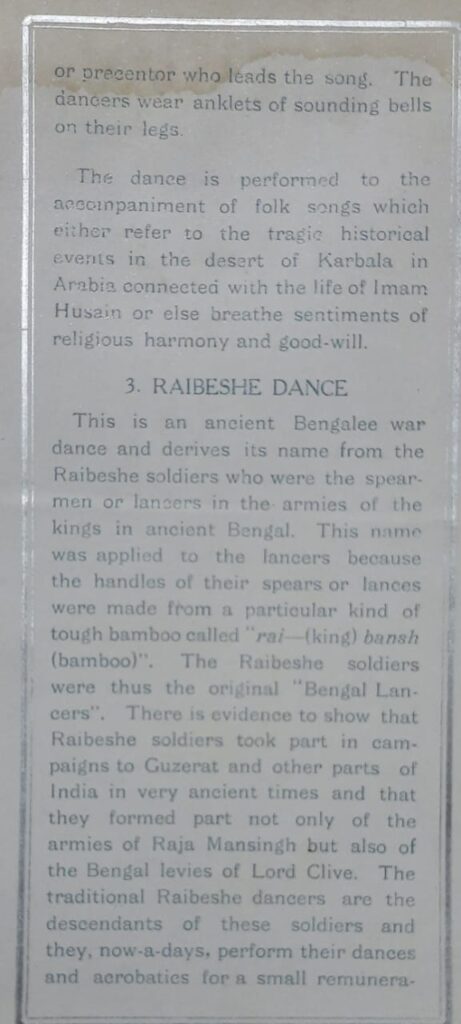

The Santal Mission ran a boys’ boarding school and church in Kairabani, which also had a choir and a brass band. It was Bake’s friend, the American missionary Boyd W. Tucker, close associate of Gandhi, who taught English in Santiniketan, who connected him with Rev. Bodding, and the latter then invited him to Kairabani, since he was interested in recording Santali music. After a few aborted plans owing to bad weather and the unavailability of Mr Gurusaday Dutt–the district magistrate of Suri, who would facilitate the trip–the Bakes finally set out for Kairabani, 30 kilometres southwest of Dumka, on 17 March 1931.

The Kairabani Mission school now, photographed by me in January 2017.

Kaerabani (Kairabani) missionary bungalow, built by the German Baptist Missionary, Albert R. Haegert, who died 1904 (then the house was bought by the Santal Mission in 1905). The photograph is from the digital library of the University of South California. Source: Danmission Photo Archive. Rights: CC Attribution (CC BY). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Permanent link http://doi.org/10.25549/impa-c123-98602

After the trip, Bake wrote to Erich M. v. Hornbostel at the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv that this was just the first trip, he would have to go back to record the Santals again. Mostly because he could not record Santal dance in the mission as those who rain the mission were not keen on dance. Bake could not go back to Dumka, however; instead, he the recorded and filmed the Santals at Kankalitola and Mongoldihi, nearer home, in Birbhum later that year.

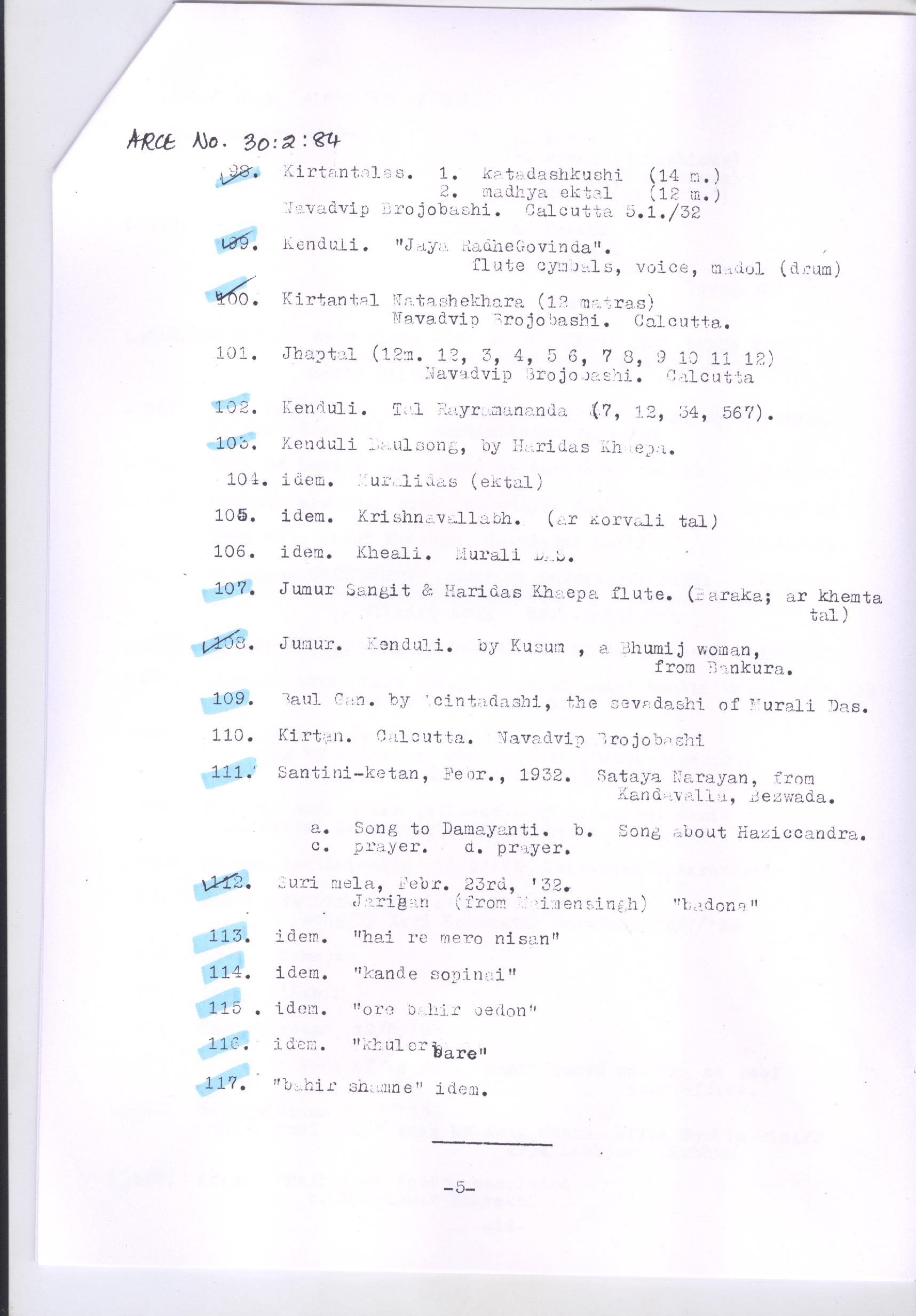

Film copy received from Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology (ARCE), Gurgaon.

Bake India I, Cylinders 1-8, were recorded between 17-20 March 1931 in Kairabani. It is with those recordings that I went with sound recordist Sukanta Majumdar to Dumka on 21 January 2017. Some recordings from that trip can be heard here. Achyut Chetan, who taught then in the local S. P. College and whom I knew through a friend in Santiniketan, put me in touch with Father David Madhava Solomon, SJ, Director of Johar Human Resource Development Centre, also in Dumka, Jharkhand and that became our starting point. Sushant Soren, a young activist who worked with Johar, was our main guide and interpreter on this trip. I have travelled to the field with companions but rarely with an interpreter or guide, but this trip was different. I was consciously aware of my distance from the field, the language and the subject I was seeking to explore, from the very onset of the journey.

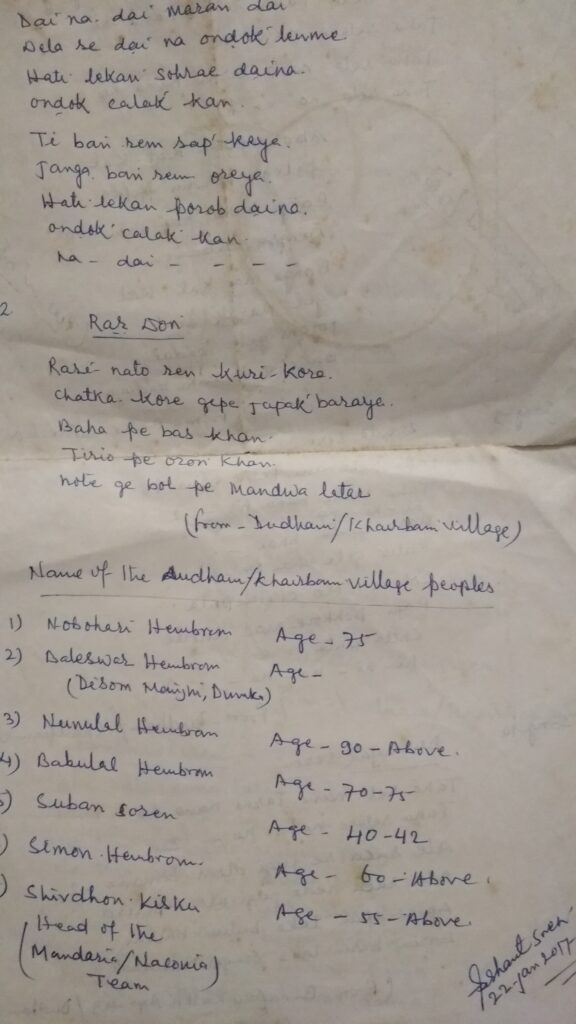

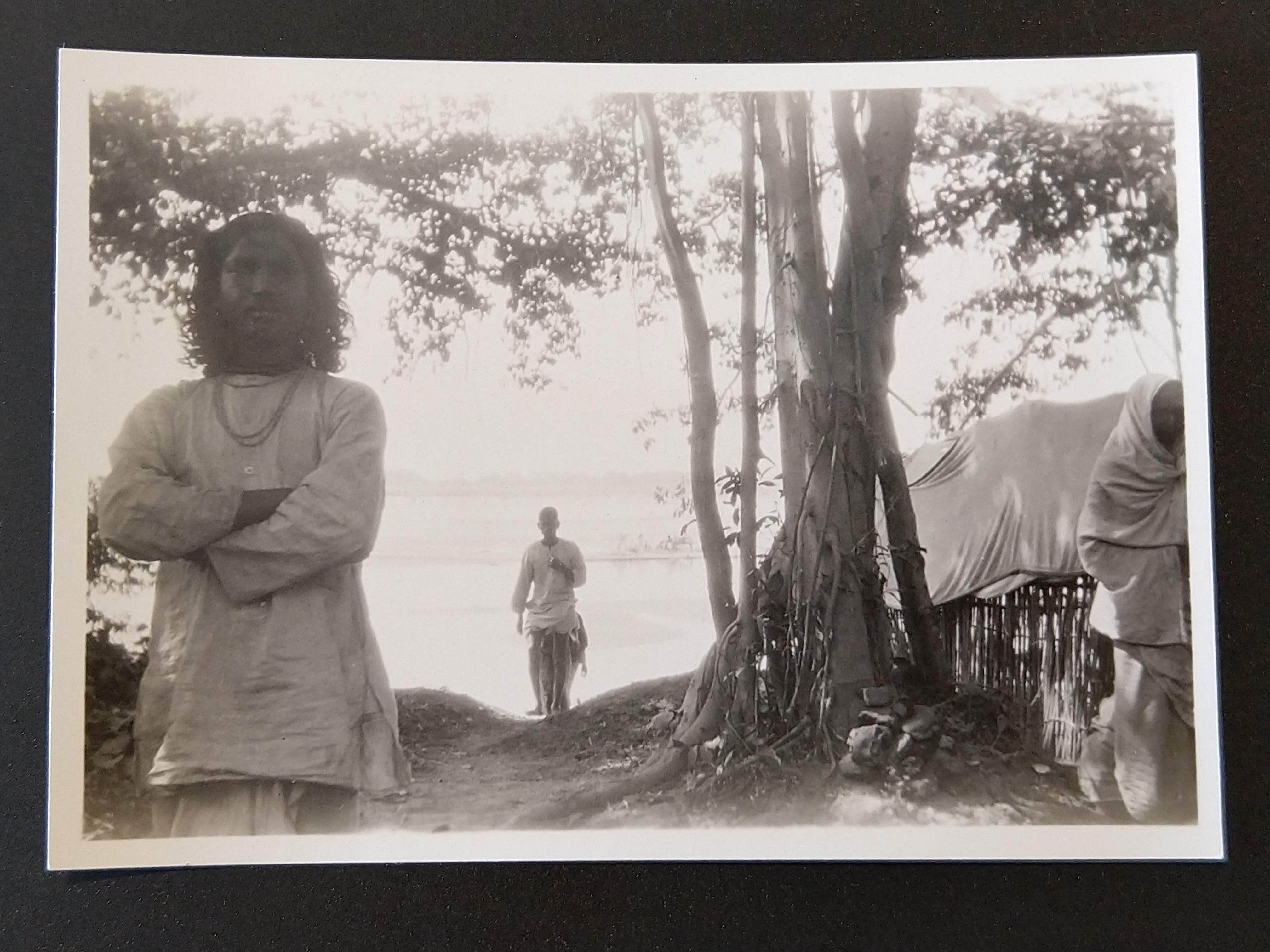

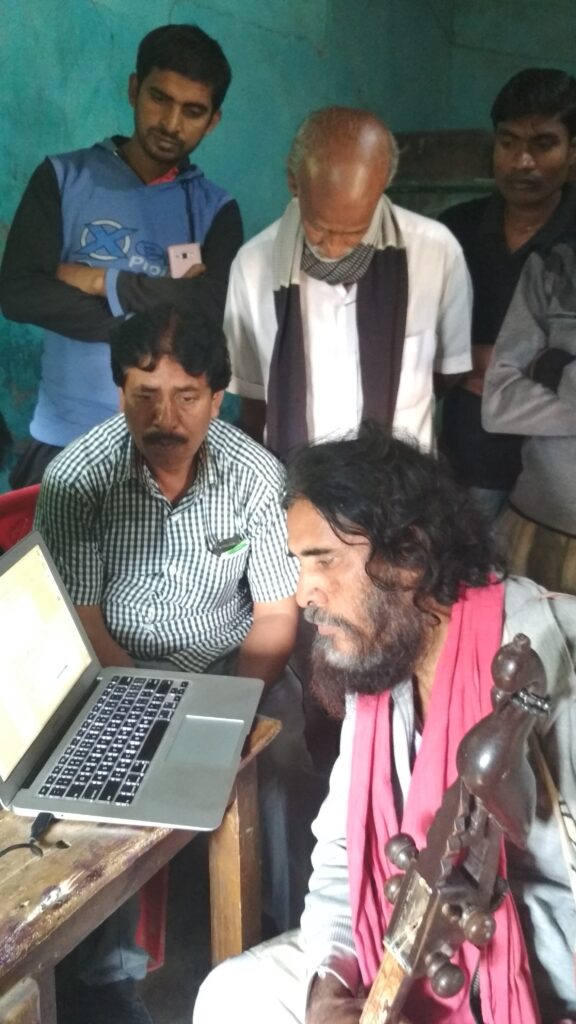

On 22 January 2017, we went to Kairabani Dudhani, the village where the Kairabani Mission was situated. We sat on the veranda of a house from where the Mission could be seen, but the villagers who had gathered were not attached to the church. Rather, they were quite critical of the role of the church in their communal life. Slowly a crowd of some 20-25 people gathered as we sat on the floor and played the songs. I explained the context in Hindi, Sushant Soren translated what I was saying into Santali, and the songs were played from the laptop, through portable speakers. The villagers listened and responded and chatted amongst themselves and Sushant translated some of their responses back to us and some things he left out.

Listening in Kairabani, 22 January 2017. Photos, The Travelling Archive.

Interestingly, Sushant Soren, with his notebook and pen, was also an outsider in Kairabani. What he said was explained to the villagers by one member of their group who had a job with Calcutta Telephones, Shivsadhon Kisku, about 55 years old. Kisku spoke fluent Bangla and Hindi.

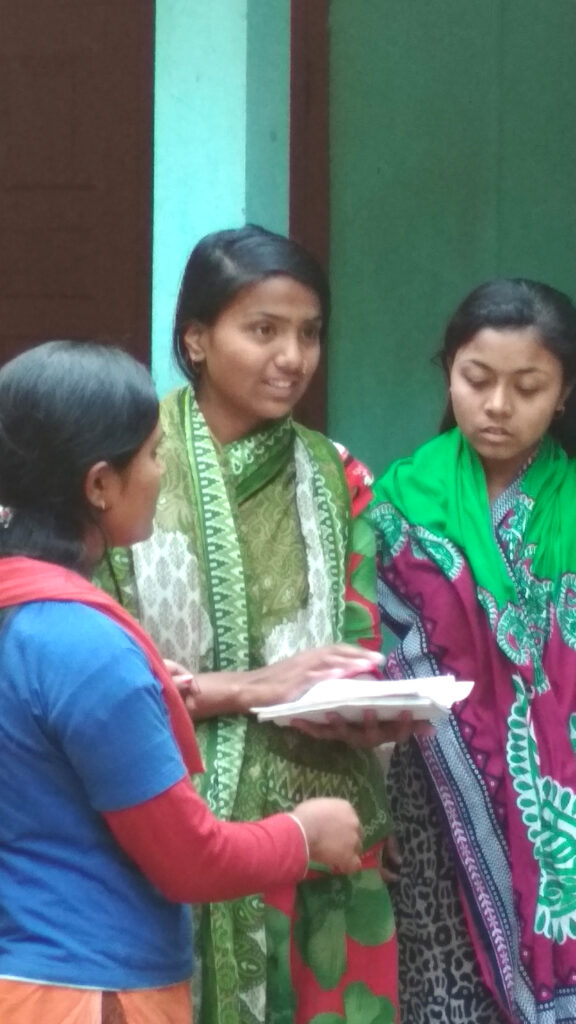

Sushant Soren and some of his field notes.

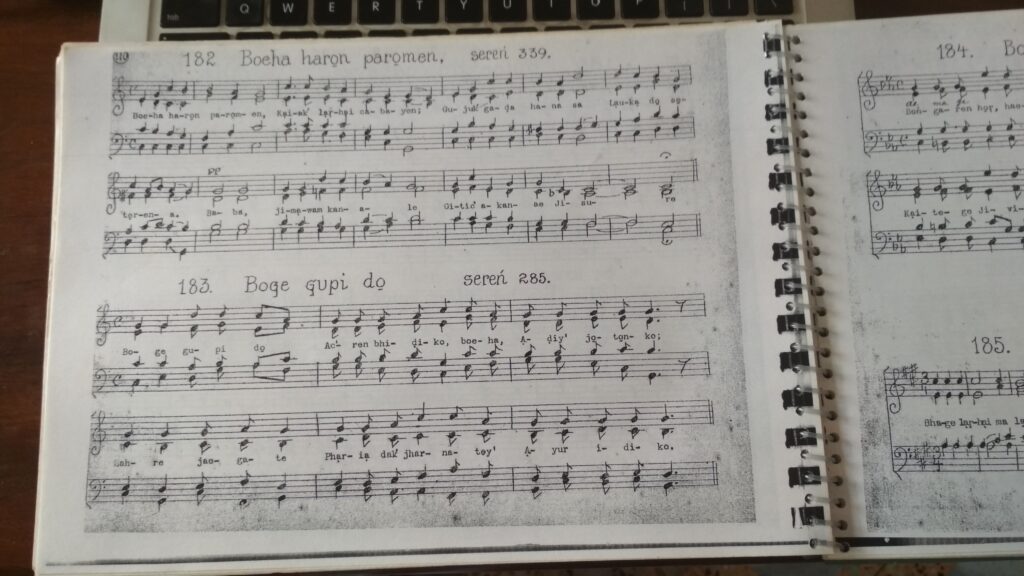

Arnold Bake’s Dumka recordings are of songs ranging from the Santali church song of the good shepherd, composed by the Norwegian missionary Lars Olsen Skrefsrud (Boge gupi do, song 2 of cylinder 1) to the same song sung as a four-part harmony (song 1 of cylinder 2), a do̠ń seren or wedding song about the ‘famine which happened five years ago’ (More serma akal keda, song 3 of cylinder 1). Then there was a flute tune (song 1 of cylinder 1) which the community of listeners in Kairabani Dudhani identified as a melody played during Sika̠r, which is the annual hunt festival—a communal gathering of only men, when disputes are resolved, while there is singing and dancing, food and alcohol through the night. There was also a song about the train (Nawa nawa railga̠di, song 2 of cylinder 7) and a song about Boṅga buru or the nature spirits (Abo manwa kal kal, song 1 of cylinder 6, identified as Sõhãṛe by BLSA, but described as rar danta by the Kairabani Dudhani people).

That morning, we recorded for more than two hours. I am keeping here some short video clips from that session. They were recorded by Sushant Soren (where I am seen) and by me too.

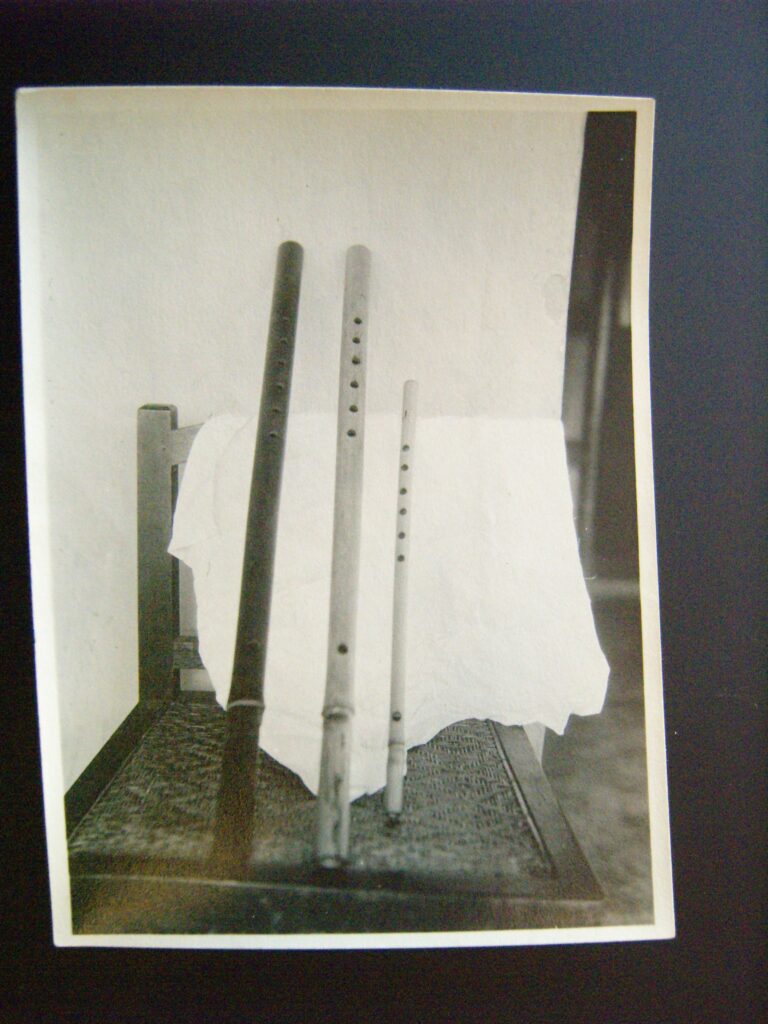

While traditional instruments such as the tirio flute and ḍhud̠ru banam are played in these recordings, sometimes to accompany the song and sometimes as solo pieces, the songs are marked by the absence of percussion. This absence somewhat denaturalises the songs, because Santali songs are essentially about drums, beats and rhythms; the songs are also inseparable from dance. When we were recording in Kairabani Dudhani in 2017, the crowd which had gathered were slowly warming up to the session and finding it fun to listen, talk and sing, and seemed to like the idea of being recorded. The madol player was also there. Before starting a song , they said, there is no madol here. They could distinctly hear, despite the noise of the cylinder. Can we play ours? they asked, much to our embarrassment. As if it was for us to decide.

They brought their drums to the listening session in Kairabani. January 2017. Photo, The Travelling Archive.

Who exactly were the singers Bake recorded in Kairabani? Did they stay in the boarding? This question has kept coming back to me. It troubles me that here are no name for the singers for these archival recordings. ‘There are young boys and older ones, and also adults, who come for training as a village teacher,’ Bake had written in a letter to his mother on 25 March 1931. There is no other detail.

The Kaerabani (Kairabani) School Brass Band visiting Narainpur on 9 March 1931. Standing on the left are David Jha, Bernhard Helland. Muriel Helland and Jakob O. Soren are on the right. The photograph is from the digital library of the University of South California. From the Danmission Photo Archive. CC Attribution (CC BY). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Permanent link: http://doi.org/10.25549/impa-c123-98657

The Norwegian director of the school, Rev. Bernard Helland, and his wife Muriel hosted the Bakes in Kairabani. This is a photo of a photograph from the Arnold Bake Collection, Special Collections, Library of the University of Leiden, taken during my first visit to the library in 2010.

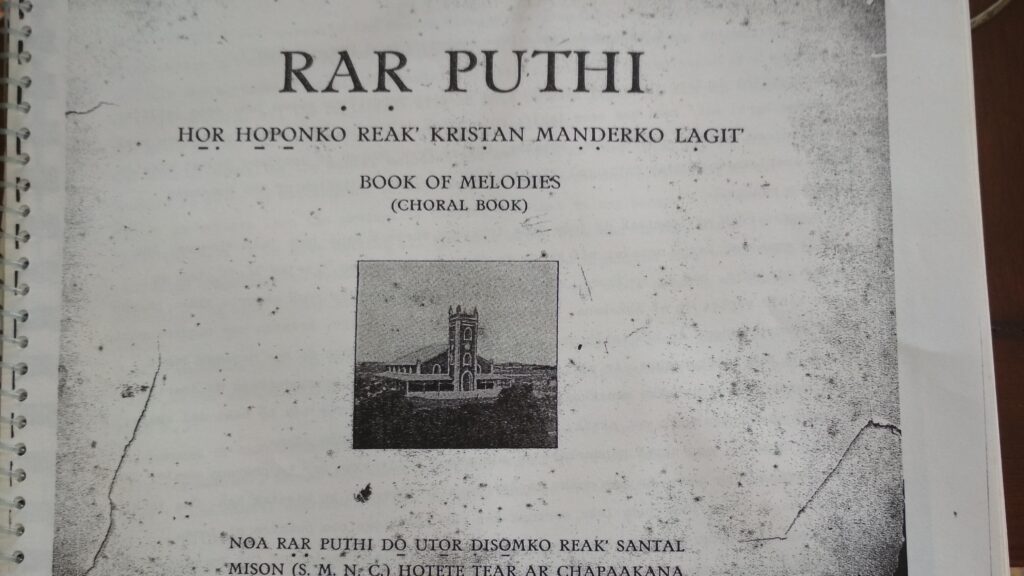

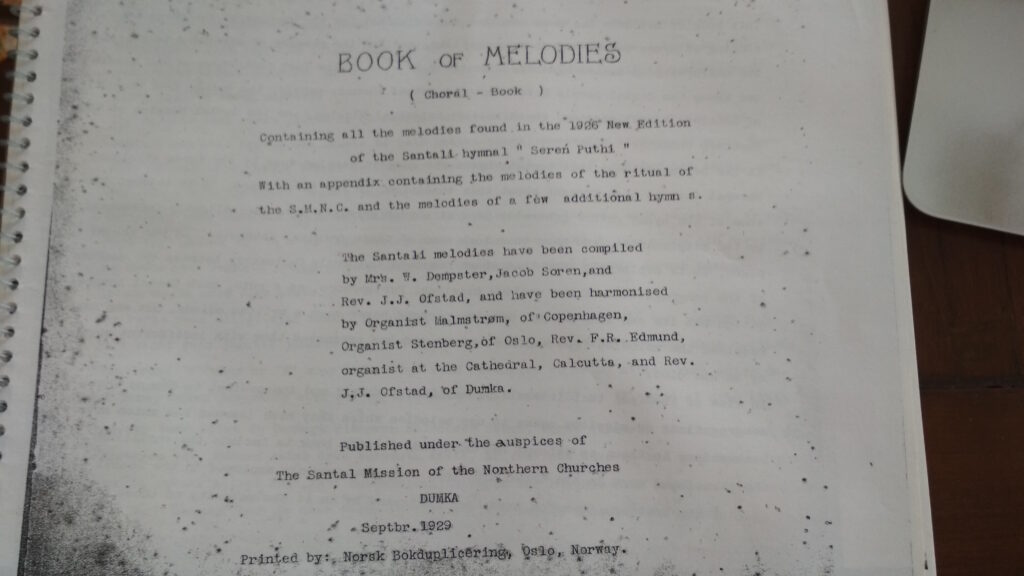

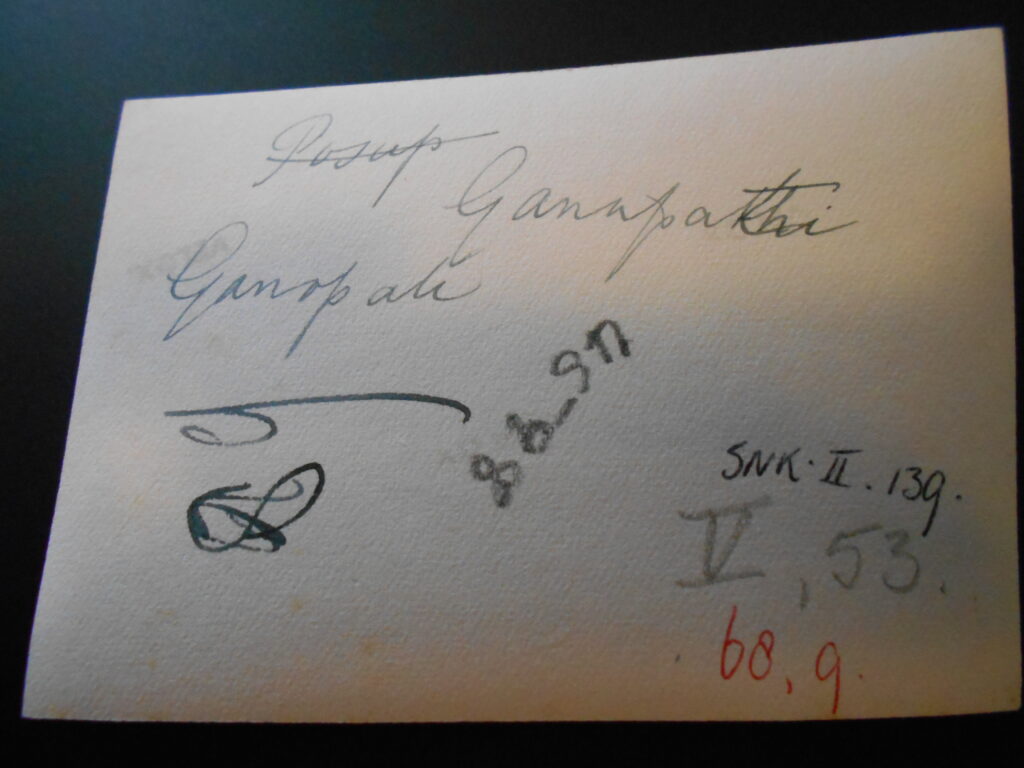

I made inquiries after the Dumka trip to see if there was any way I could have a register which gave the names of the Kairabani singers. After all, they were members of the mission choir. However, for now all I know is that J. J. Ofstad (Rev. Johan Johansen) was the music teacher of the school, Jacob Soren was his Santal assistant. I believe that Ofstad wrote a booklet about the Kairabani Mission, perhaps it has some names, but I have not had the opportunity to see it. All I have seen are the song books Seren Puthi and Rar Puthi. On 24 January 2017, we had gone to Jamuasol near Dumka to meet Mathias Hansda, who was a student of Kairabani High School for eleven years from 1951 and later became a teacher. He was also a member of the school’s brass band. He could fill in some details about the school and the practice of music; the school’s music teacher was Benjamin Murmu, who was a student of Jacob Soren, who in turn was a student of J. J. Ofstad. But he did not have any specific information about the singers, perhaps I could contact Benjamin Murmu’s daughter, Gloria, he suggested. That is as far as I have been able to get in my search for names, which is not saying much, I am afraid. But the important thing about research is also the questions, I think. Someone else can then try to answer them, if we can’t.

Mathias Hansda reminisced about his days in the Kairabani Mission school, as a student and teacher, about the school band, his teacher Benjamin Murmu, listened to the recordings, sang a little bit and talked about how things change over time, through rahan-sahan; that is, in the course of one’s life. This is a short clip from that conversation, in Hindi. 24 January 2017. Photo: The Travelling Archive.

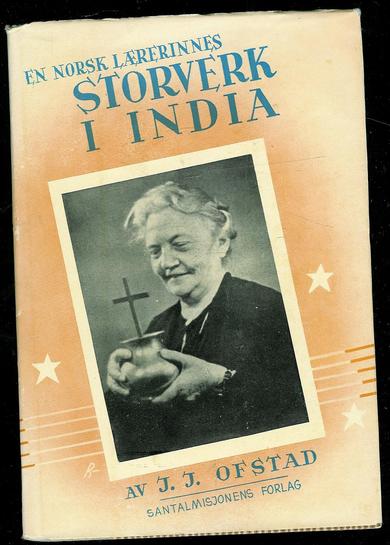

En norsk lærerinnes storverk i India (A Norwegian Teacher’s Great Work in India), by J. J. Ofstad (1879-1963)

Before visiting Mathias Hansda, that morning on 24 January 2017, we had been to the NELC radio station in Bandorjori, Dumka, from where they broadcast church-related programmes in Santali. The Northern Evangelical Lutheran Church (NELC) in Dumka is the successor of the Santal Mission of the Northern Churches. Mathias Hansda also mentioned the NELC radio station, which used to be run by the American missionary, Naomi Torkelson. A radio station, even if it is set up for the purpose of spreading the faith, will have sonic records of history, just as Arnold Bake’s cylinder recordings from Dumka are also a record in sound of a time.

On the wall of the NELC recording studio in Bandorjori, Dumka hung a photograph of Lars Olsen Skrefsrud, the Norwegian missionary who had composed the song of the good shepherd, ‘Boge gupi do’, which Bake had recorded. Photographs: The Travelling Archive, 2017.

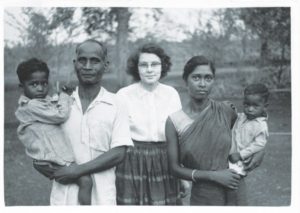

What drove a young woman all the way from Ohio to the Santal Parganas and what kept her stationed there for decades? I arrived at these images from the sounds of Arnold Bake’s cylinders. The photographs provoke such questions and the answer is never simple. The more I have delved into Arnold Bake’s Santal recordings, the more inadequate I have felt while also knowing that here lay a vast site worthy of long-term excavation. The photograph on the left is from the Danish Santal Mission or DSM’s annual meeting in Nyborg, 1986, where the American Missionary Naomi Torkelson (right), secretary of NELC, is seen speaking to the audience, with Rev. Inger Krogh Nielsen translating. The photograph is from the digital library of the University of South California. Source: Danmission Photo Archive. CC Attribution (CC BY). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Permanent link: http://doi.org/10.25549/impa-c123-99919. The photograph on the right, which I sourced from the internet, can be shredded and each strand separately analysed. Who are the people in it? What is Naomi’s relation to them?

The photo on the right is as thought=provoking as as some of the songs Bake recorded; they led to so much debate and discussion. Take the song ‘Boge gupi do’. In Kairabani Dudhani, the listeners could not really engage with the song. That is a church song they said, listened once, listened again and got busy talking among themselves and then they said they did not know what song it was. So, we moved on to the next song. In Johar Human Resource Development Centre in Dumka, on the evening of 22 January 2017, a group of artists and intellectuals sat in a circle and listened to Bake’s recordings, and they were led into the discussion by Father Solomon. They were all connected with Johar and all of them were possibly church-going Christians. Their connection with the song was immediate.

Listening to Boge gupi do in Kairabani. Recording by Sukanta Majumdar.

In Johar, we sat in a meeting with a group of Santali intellectuals and artistes, including singer Babita Murmu, Sebastian Soren, musician, Emanuel Soren, social actvist, Bijoy Tudu, government officer, Suleman Marandi, teacher, Sanatan Murmu, bank manager and others; Father Solomon, a Tamil who spoke many languages with great ease, navigated the course of the listening session. There were more nuanced debates here on the significance of words, form of song, slight regional variations of style.

Boge gupi do at Johar. The listeners immediately connected with the song.

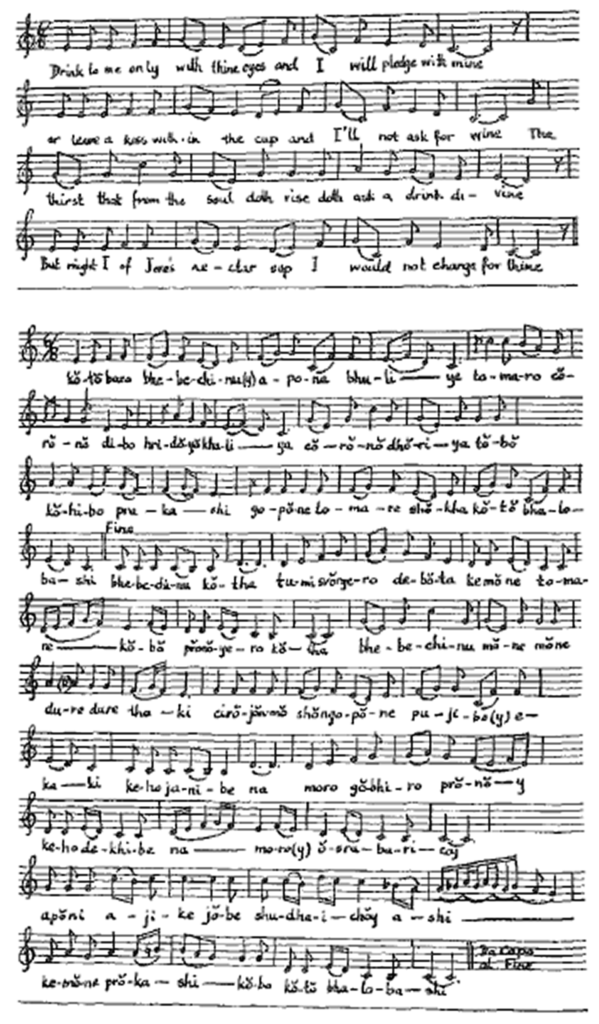

Pages from J. J. Ofstad’s Rar Puthi: Book of Melodies (Dumka: The Santal Mission of the Northern Churches, 1929), including the song Boge gupi do. We got a copy of the book from NELC.

While the church was taking root among the Santals, songs and rituals and local knowledge were also getting recorded for posterity.

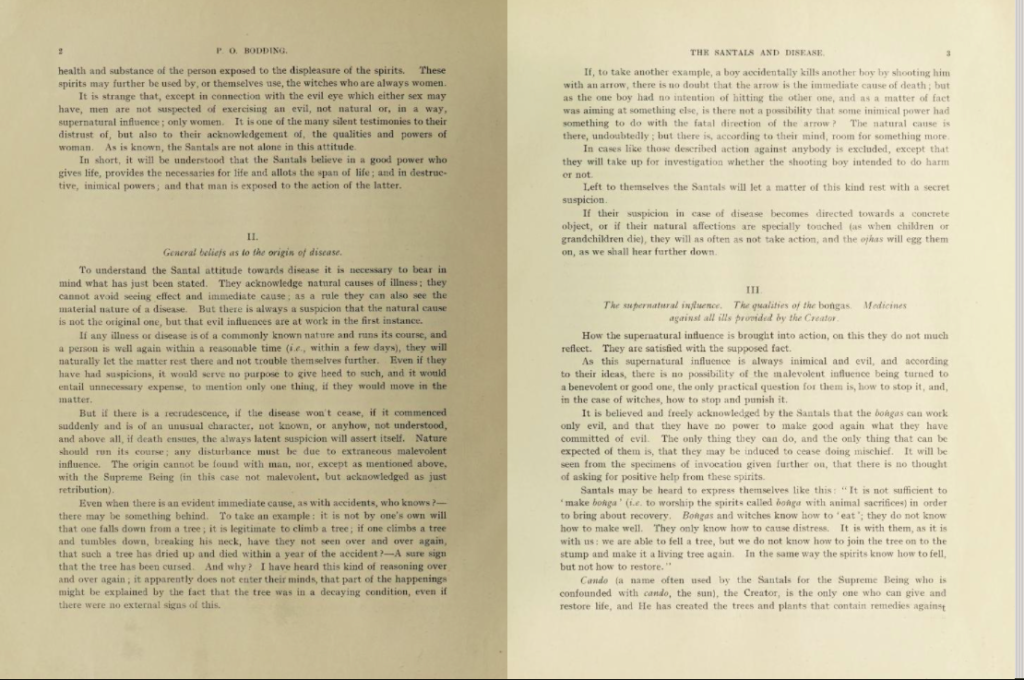

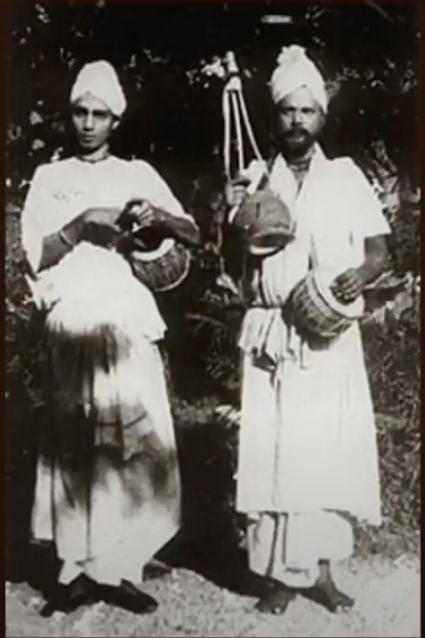

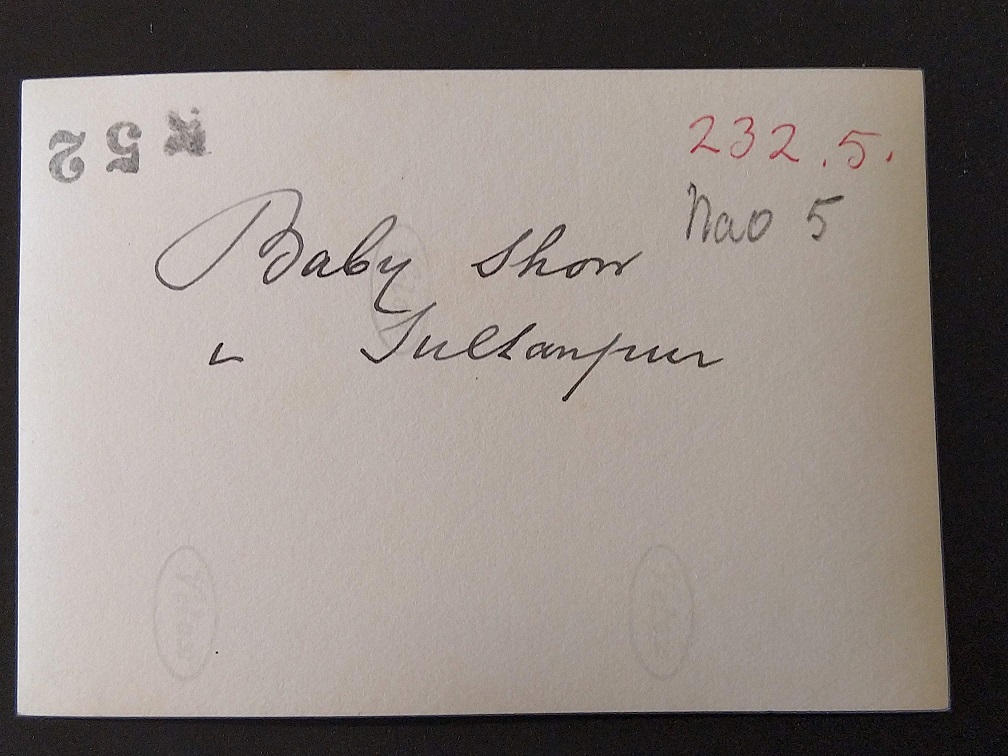

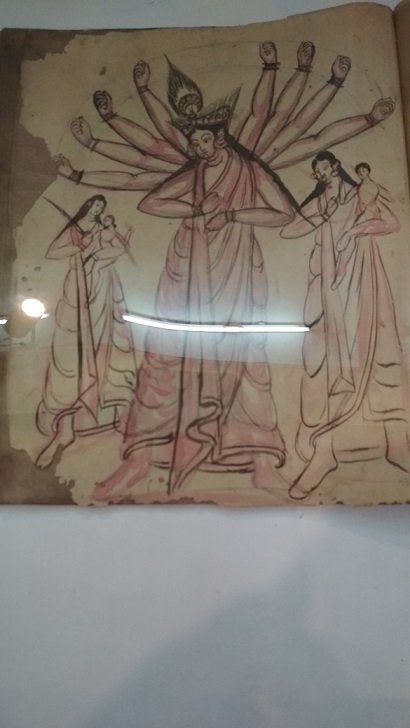

There was a song the listeners of Kaiarabani Dudhani sang for us, ‘Ot́ma lo̠lo̠’ (song 3, cylinder 4), which is sung during Dasãe. Rev. P. O. Bodding, in his Studies in Santal Medicine and Connected Folklore (Kolkata: The Asiatic Society, first published in 1925), wrote in detail about the annual Dasãe festival in the month of the Dasãe or Ashwin, which is also the time of the Hindu festival of Durga puja. ‘This is naturally not a Santal festival; it is celebrated by the many Bengalis living in the country, the Santals participating as active spectators.’ Bodding wrote about young Santals going to see the idols and ‘sometimes [they are] even hired to carry it [the idol].’ This is the annual festival which marks the end of a three-month training the ojha or guru, the master medicine-man who knows all about plants, medicine and healing, has given to his all-male students. The festival marks this passing down of knowledge, as the young men and their teacher, dressed in kạcni (kind of skirt) instead of the ordinary ḍeṅganak’, or loincloth, and wearing turbans (there are aspects of cross-dressing here), carrying peacock feathers and the musical instruments buan and kabkubi, go wandering through villages, singing and dancing, gathering food from the people for the feast later in the evening.’

Page from Bodding’s book

The day after we went to Kairabani, on 23 January 2017, we went to Harinsingha, a village also in Dumka.

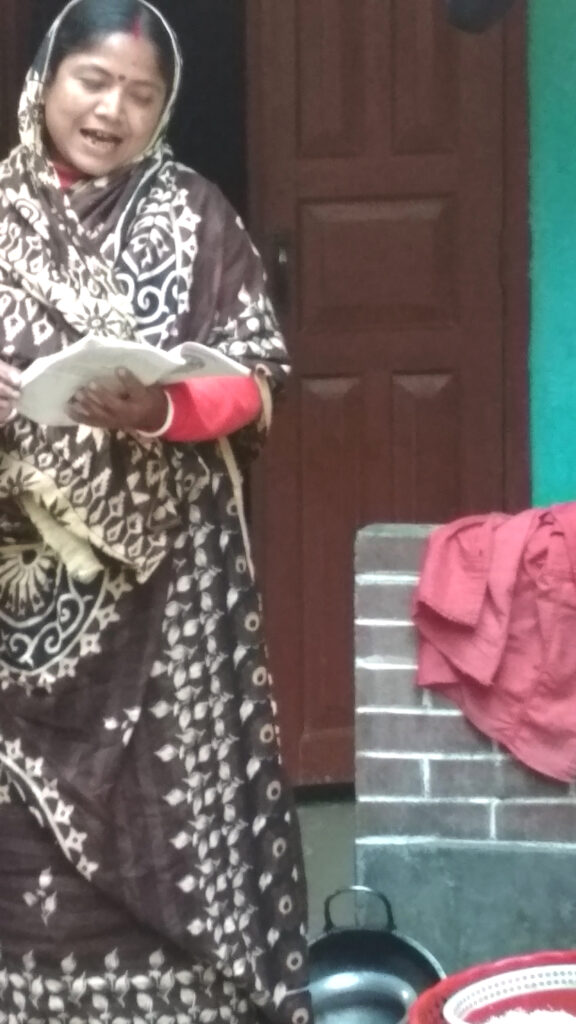

Sushant Soren, Habil Murmu and Aruna Hembrom, all Johar Human Resource Development Centre staff, took us to Harinsingha, where they run advocacy projects, making people aware of their deprivations and the rights they are entitled to, and help them fight for those. This village was very different from Kairabani Dudhani. Things were far more in order, organised, and the people seemed also economically better off. Many men and women had gathered in the house of village jo̠g ma̠ńjhi (community leader) Motilal Murmu; they had brought their children along. The women were beautifully dressed for a special day, in their traditional green two-piece saris. The courtyard was teeming with life. This was clearly a village where they were taking special care to reclaim their heritage, they had songbooks, practiced music and dance, and thus they were also especially interested in the songs we had brought with us. It felt like there was a kind of cultural revivalism going on here, as the women washed our feet first while we sat on chairs; they said that is how guests are treated in their culture, while I felt that in order to be the good guest and good researcher, I was having to throw all class, caste and gender consciousness to the winds. (I am glad I haven’t had many such experiences over my decades of fieldwork.)

If we listen to the Harinsingha listeners’ response to the railgadi (locomotive) song that Arnold Bake had recorded (Bake India I, Song 2 Cylinder 7), we will be able to hear the confidence in their voices and preparedness.

Kolgadi calak acte’ge sung by the villagers of Harinsingha, Dumka

In his 1937 essay, ‘Indian Folk-Music’, published in Proceedings of the Musical Association 63 (1936-1937), Arnold Bake had written of the Santals, ‘an aboriginal tribe of Munda stock which inhabits the hilly country on the borders of Behar and Bengal in the middle South-east’, that these people, ‘agriculturists where they have not flocked away to rice-mills or railway stations in which they work as labourers, are great hunters with bow and arrow. Even when living amongst the Bengalis where there is no hunting to be done, the men are very often seen carrying bows and arrows, Next to the drum, their beloved instrument, is the bamboo flute of unequal length with six holes. They often use their flutes as walking sticks and once I saw a combination of flute and stringed instrument where a Santal had fixed one string along the length of his flute and used that after the fashion of religious beggars to give the drone to his songs. This however was definitely an innovation not belonging to Santal music proper. They have preserved their independence of language, religion and music through decades of close contact with Bengalis and it is only under mission influence that they are now changing all of these, It was a sad experience to hear them sing their changed folk-melodies, in four parts, to religious words after the fashion of our hymns. The fact that their music has not reached the melodic perfection of Hindu India apparently makes them take to part-singing with greater ease than I have noticed anywhere else in India.’ Much prejudice in this remark, ideas of cultural evolution at work, but here in this video, the listener-performers of Harinsingha were demonstrating how a certain flute is made and how it works, to the great amusement of others.

Arnold Bake spent time measuring the distance between the holes in the Santal flute and sent his measurements to the archive in Berlin. On 15 April 1931, he wrote to the director, Austrian ethnomusicologist Erich M. von Hornbostel, ‘I include here two pictures of the Santal instruments, flute (which I have here) and banam. I will take pictures of the drums later. The drum is the most important. The flutes are always made in pairs. The two big ones are a pair. I will send you the measurements:

Length (of the great flutes, which are exactly the same) 72 cm

Thick (measured in a circle) 10 cm

Average (Outside Dimension)

Average (internal dimension) 22 millimetres

Length (up to the knot of the bamboo) 12 Ω cm

Length (up to the middle of the blow hole) 18 // 4 cm

Removal of the first finger hole from the blow hole 25 cm…’ (Translation from the German original by Debjani Das. Letters kept at the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, copies of which were kindly given by Professor Lars von Koch)

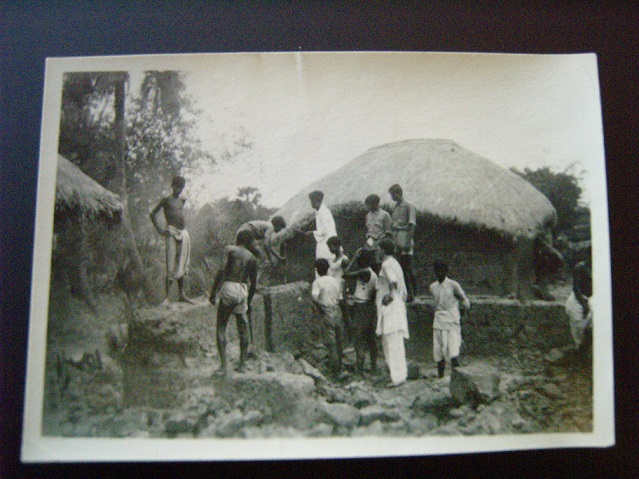

Photos of photos which I took while studying the Arnold Bake Collection at Special Collections, Library of the University of Leiden in 2015.

On the first day, when we met artistes and intellectuals at Johar in the evening, as we were playing Bake’s Santal recordings, they listened to the first flute of the fourth cylinder and responded with a beautiful song about the jugi, who goes from house to house gathering alms in exchange for telling people about their forefathers, even showing them their ancestors’ face. That song is in our recording session note for that trip in 2017, Babita sang it a second time for us to record better, coming closer to Sukanta’s microphone. ‘The jugi or traveller has come visiting, and the poet requests him to show the face of his dead parents. Show me my parents’ face, because after death, they have become faceless. How will I see their “roop”, how will I get their love?’ They explained the song to us and told us about ‘jong baha’, the ritual of floating the ashes of the dead. In a sense, Bake’s cylinder recordings are like the ‘jugi’; they have the power to show us the ancestor’s face.

Nunulal Hembrom, more than 90 years old in 2017, walks back after our listening/recording session in Kairabani. I do not know where he is now. Photo: The Travelling Archive.

Postscript

My friend and longtime collaborator, musician Satyaki Banerjee, shared a video with me, some time in May 2022. A friend of his, Sukrit, had recorded it when he went to a workshop on Adibasi (indigenous people) dance in Tepantar Theatre Village in the border of Birbhum and Barddhaman. I was quite startled to see it. There was someone playing a flute of the kind the listeners of Kairabani were describing to us (see video above). This seemed to me to be that flute with two parts. Sukrit wrote to Satyaki that the man with a hibiscus in his ear is Subal Hembram, he makes his own flute, which is supposedly called the ‘chyng murli’. He plays for himself, just like that.

Sukrit’s message to Satyaki: ‘Ami 11mile er tepaantar e ekta adibasi nacher kormoshalay chilam bigoto der mas, eta sune khub valo legechilo, tai tomake pathalam. Olpo olpo bujhi, je mul harmony ta lead korche tar nam mungli di, onake jigges korle valo bolte parbe. Eta bodhoy biyer gaan […] tumi chaile tomar satheo kakhono alaap koriye debo, manush gulo koto sundor, churaanto aesthetic. Hyaa go, nijer monei bajiye Jay, etar nam naki chyng murli, r ek kaane jobar dnati kaner fnuto diye dhokano, odbhut ei lok ta satyaki da. Ei jontro ta enari nijer haater banano, subal hembram.‘

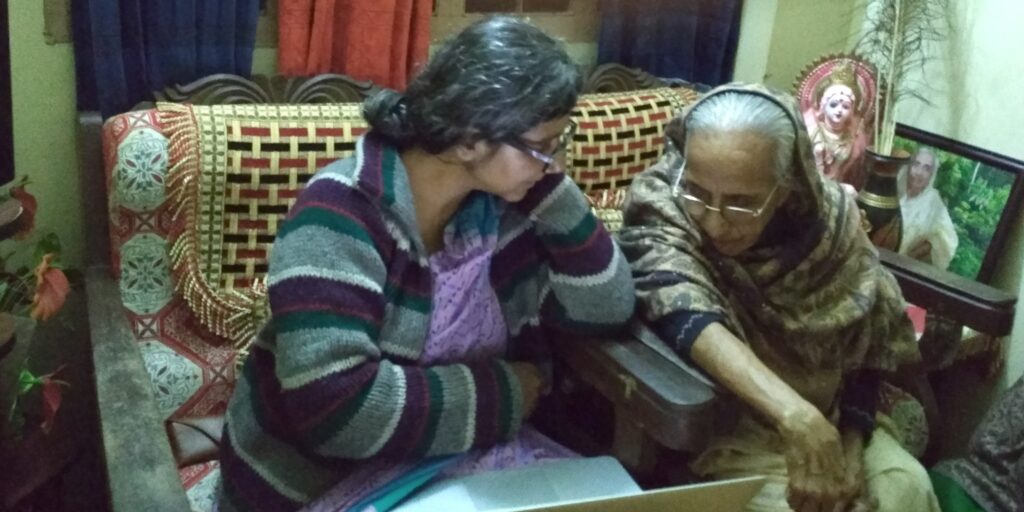

She can hear what we can’t because she knows what to listen out for. She can also listen to absent sounds, because she knows where they were supposed to be. I went to meet her with her with the disembodied voices of Arnold Bake’s seamen, plucked from the sound archive. On 15 January 2018 Ambarish Datta and I went to meet 88-year-old Sushoma Das, for she is someone who keeps songs in her body. We knew she would hear more in those recordings than most people we know.

Sushoma Das in her home in Sylhet in January 2018

I first met Sushoma Das in 2006, through Ambarishda, whom I also met for the first time that year. I have gone back to Sylhet many times since and recorded Sushoma Mashima (mashima meaning aunt) and many others over the years, while Ambarishda has become like family. In 2012 we brought out an album of field recordings of Sushoma Das and Chandrabati Roy Barman (1931-2014) . Sushoma Mashima has the strongest voice and a phenomenal memory even at this advanced age; she stands like an old banyan tree in our present time of feeble voices and callous oversights. On this day in 2018, when I was visiting Mashima with Bake’s recordings, she sat there in her room, frailer and thinner since the last time I saw her in 2015. Besides Ambarishda, and the Sylheti folk song collector and researcher-writer Suman Kumar Dash (who came in late), her daughter Bashona, sons Prashanta and Probir, and a neighbour, Madhab Chandra Das, were present in the room, while other family members walked in and out with water, tea and sweets. I sat on a chair next to Mashima and play her Bake’s sailors’ songs from my laptop. The noise on the surface of the cylinder envelops the voice, it is not easy to listen to the song, especially from the speakers of the laptop, what with outside noises of people talking, work in the kitchen and vehicles on the streets below and beyond. Yet Mashima became immediately alert. In fact, it wasn’t just Mashima, but everyone in the room seemed able to listen to something that we could not hear, as they listened with their insider knowledge, as we have seen in many other places.

I begin by playing two songs recorded on Bake India II Cylinder 341 A, recorded on 1 April 1934. They are credited to Sayed Ali, sailor from Hirpur (Comilla p.o.). One is labelled in the archival note as ‘Hridoy jole’ (The words go, ‘Elo re basanta, hridoy jwole’, meaning, it is springtime and my heart burns). The other has a one-word description, it is called just ‘Amay’. The line sounds like this: ‘Bhuilo na bhuilo na amare’, do not forget me. Sushoma Mashima says each place has its own way of singing, but these were not from Sylhet. I say, yes, that is what the note says. The singer was from Comilla. ‘Wherever it is from, the song about basanta or spring is a biraha (song of separation and longing)’, she says. She is slowly getting used to the sound of the cylinder. Then I play ‘Pranonath bondhure’, sung by Fayazullah, stoker from Damrasari, Sylhet.