Imam Bux Boyati of Mymensingh at Gurusaday Dutt’s Suri Mela

Imam Bux Boyati and his team, were jarigan singers from Atharobari, Mymensingh. They were recorded twice at the Suri Mela, Suri, district headquarters of Birbhum; first on film in 1931 and then on wax cylinders, Bake India II/112-17 the next year. It was Gurusaday Dutt (1882-1941), the district magistrate, who used to organise this festival.

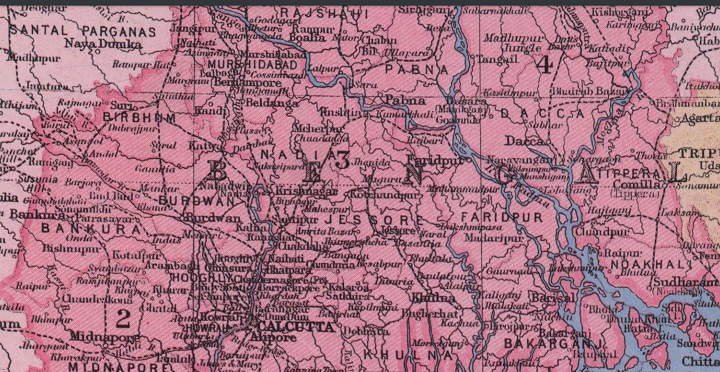

A section of a map from the Imperial Gazetteer of India Atlas, India and Sikkim 1931. Map kindly shared by poet and comparativist Taimoor Shahid. Original can be accessed here.

Arnold Bake’s field trips in and around Bengal were facilitated by Gurusaday Dutt, who was not only the district’s principal administrator but was himself a compulsive collector of folk songs and dances and craft of undivided Bengal, and a folk revivalist who had started the Bratachari Movement, ‘that blended nationalism, folk dance, “aerobics” and physical fitness, encouraging self-confidence, especially among women, spread throughout India. But its original inspiration was the Bengali village,’ as art historian Partha Mitter wrote. With such shared interest, it was natural for Bake and Dutt to become friends.

Jari dance from Mymensingh at Suri Mela in 1931. Filmed by Arnold Bake. Copy of film from Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology (ARCE), Gurgaon, with kind permission. No copies of this may be made without ARCE’s permission.

In 1932, Bake recorded extracts of jarigan, where the singers began with the invocation or bandana gaan to the Creator and protectors, divine and human, and went on to sing vignettes from the tragic Battle of Karbala (680 CE). On 23 February 1932, Arnold Bake wrote to his mother, ‘We went to stay for just a day, but when we were there we discovered such interesting things, that we decided to stay until Tuesday night. I managed to get hold of the songs that I missed during Gurudev’s parties in Calcutta. Moreover, on Monday night, we saw some dances from Faridpur that were incredibly interesting. […] Our visit to Suri has been fruitful; just meeting Shivratan Mitra would have made the journey worthwhile, and I am so very happy that I finally managed to get the songs that go with the dances that I filmed there last year.’ (Translation from the Dutch by Jan-Sijmen Zwarts)

Interesting that Bake should talk about Faridpur, because the jarigan singers and dancers were from Mymensingh. Who then is he talking about? Could it be that while the leader of the jari team was from Mymensingh, the dancers and singers were also from Faridpur? I am confused. Faridpur though has been such a special place for The Travelling Archive, and you will see that if you go through the rest of the website. We had the first taste of jarigan here. Then there is also the work of Mary Frances Dunham, on jarigan which she had so generously shared with us. Interesting is the fact that Jasimuddin, the folk poet and song collector, was from Faridpur and we can hear him on Dunham’s page.

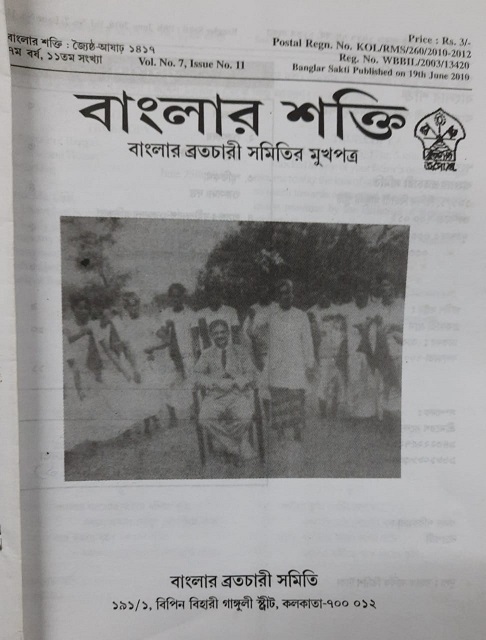

Gurusaday Dutt with Imam Bux Boyati and his jarigan team from Mymensingh on the cover of Banglar Shakti 2010, originally printed in Bangalakshmi (year unknown). Photo courtesy: Naresh Bandopadhyay

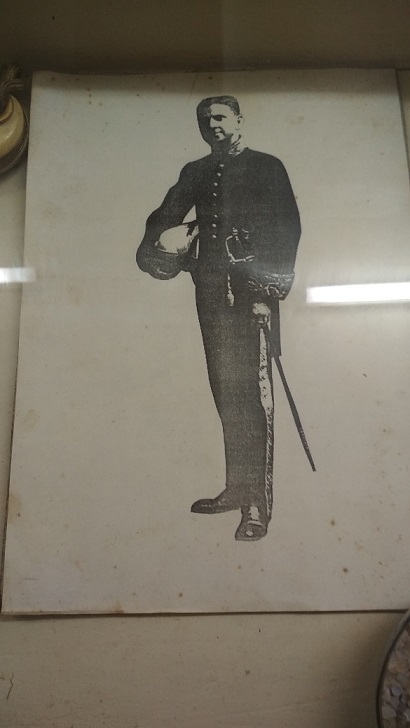

Jarigan sessions are long, as they are narrative songs which can take days to sing. Whatever could then be inscribed on a three-minute cylinder? Yet, the recordings are a record of a time, and much more. Arnold Bake did not write down the names of the singers, only that it was jarigan from Maimensingh. It is from Naresh Bandopadhyay, a Bratachari practitioner and teacher, that I came to know about Imam Bux Boyati of Atharobari. Gurusaday Dutt was methodical in the way he collected songs, dances, folk art and craft. His work did not stop with his collection but he also researched, discovered and drew conclusions about folk forms and worked all his life to propagate them, also from his station as a senior civil servant. The Gurusaday Museum was opened in Kolkata with his lifelong collection, in 1961. Sadly as I write in 2021, the museum is facing closure owing to a funds crunch and also administrative lapses. Naresh Bandopadhyay, or Bratachari Nareshji as he is called in their Bratachari circles (Dutt had introduced this system of adding the suffix ‘ji’ to every member’s name, as a mark of respect. Hence Gurusaday was Guruji), has been associated with this museum and with the Bratachari Samiti for over four decades.

Telephonic conversation in Bangla with Naresh Bandopadhyay on 20 March 2021, in which he also sings bits of songs. As an aside, it will be interesting to note the evolution of the recording device in the life of the field recordist; how we now record a ‘virtual field’ and the quality and character of the sound which comes out of it.

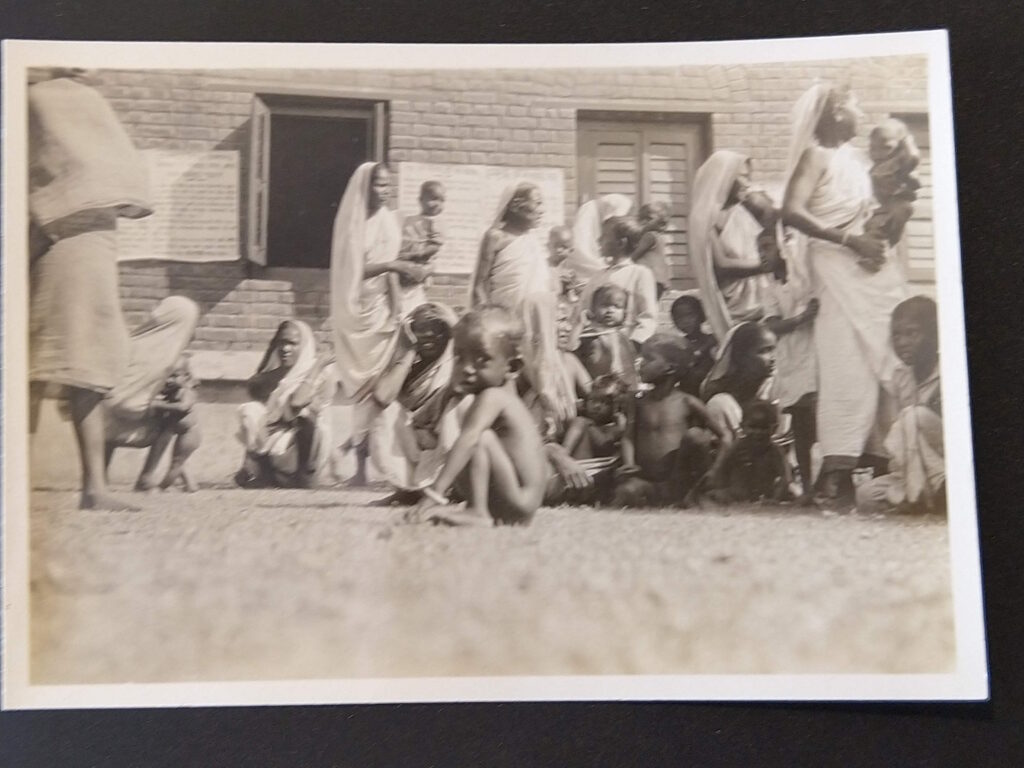

I had called Nareshji to ask for some clarification about Bake’s jarigan films and recordings, but I got much more than what I was seeking to know. Did Imam Bux and his team of singers come twice, once in 1931 and then in ’32 again? Nareshji explained the circumstances of Imam Bux Boyati’s visits to Suri Mela and elsewhere, about how Gurusaday Dutt used to travel with them to showcase jarigan and nach (dance), along with a team of Raibenshe (the martial dance of Bengal which Dutt propagated) dancers and bauls. He told the story of how Dutt found baul dance in Mymensingh and song in Birbhum and put them together, which seemed like a curious experiment to me. When was Gurusaday Dutt posted in Birbhum? After Mymensingh, right? After he was given a punishment transfer because he refused to take action against Gandhian protestors? Yes, Nareshji explained, but that was the last time he worked in Birbhum. He explained how it was not only in the 1931-32 period, when he started the Suri Mela, but from way back in 1915. Gurusaday and his social worker wife Saroj Nalini did much work for the uplift of the people of Birbhum in those early days. Later Suri Mela was designed as an agricultural fair, a platform for the farmer to display his produce—a krishi mela. There would be folk dance and music performances there too. And martial arts. That is where he brought in Imam Bux Boyati and his team, whom he had met during his posting in Mymensingh. In the above conversation, Nareshji also talked about how Gurusaday worked with Nabanidhar Bandopadhyay or Alaji, an assistant teacher of a school near Suri, in whom Dutt had seen the potential of becoming a great organiser of his Bratachari movement. Nareshji also talked about the folk dance of Bengal, Raibenshe; about how ancient it was and how Dutt had researched its mythological origins. We must remember that one of the main inspirations for Dutt’s work was Cecil Sharp in England Nareshji also mentioned Gurusaday’s work with Shivratan Mitra and his Ratan Library in Suri, the same Shivratan Mitra Arnold Bake had mentioned in his letter to his mother. He talked about the big pond with high embankment in Sultanpur, named after the Dutts as ‘Dutta Pukur’, which had been dug to alleviate the water crisis of the farmers and the local people of Sultanpur. I told him I had seen a photo of a ‘baby show’ in Sultanpur in the Arnold Bake Archives in Leiden.

The images are self-explanatory. Naresh Bandopadhyay said that since Saroj Nialini Dutt worked for/with women, perhaps this was one of her missions. The baby show was probably designed with mother-and-child health in mind. Interestingly, this image is marked Nao 5, but has nothing to do with Arnold Bake’s Naogaon trip. So, the image was probably from 1932, when Bake went to Suri, because within a few days he went to Naogaon in Rajshahi, now in Bangladesh. This photo had probably got mixed up with his Naogaon photos. Source: Arnold Bake Collection, Special Collections, Leiden University Library.

It was the name of Imam Bux Boyati of Atharobari which took me to Helim Boyati (76) in Kendua Rajibpur, Kishoreganj in Bangladesh in 2019, renowned singer of jari and puthi (there is more on Helim Boyati in the Prisoners of WWI chapter). Listening to Imam Bux Boyati’s song, Helim Boyati began to sing the same song. He reminisced about the jari festival in Bhatgaon village near Sadhur Lau char in Kishoreganj. He talked about old times, old songs, sport, days of leisure, of eating and sharing food. He described how the dancers used to wear mekurs or anklets, which were later replaced by the ghungur.

Helim Boyati in his home in Kendua Rajibpur, Kishoreganj, Bangladesh on 13 October 2019. Recording, mine.

It was Imam Bux Boyati’s song which also took me to Haresuzzaman Hares, a folk song and folk arts collector of Binnagram, Kishoreganj who follows the footsteps of his father, Muhammad Saydur, who was a famous folk song and folk arts collector. I met Haresbhai on 16 October 2019 in Dhaka, in his office in the Liberation War Museum. Amid a lot of noise of people chattering, in the new building of the museum with its hollow sound, we talked about Imam Bux and Muhammad Saydur, who had apparently recorded Imam Bux. Then we made plans to go on field trips together, mainly in Kishoreganj. Haresbhai also promised to look for his father’s recordings of Imam Bux. Some day we shall find them.

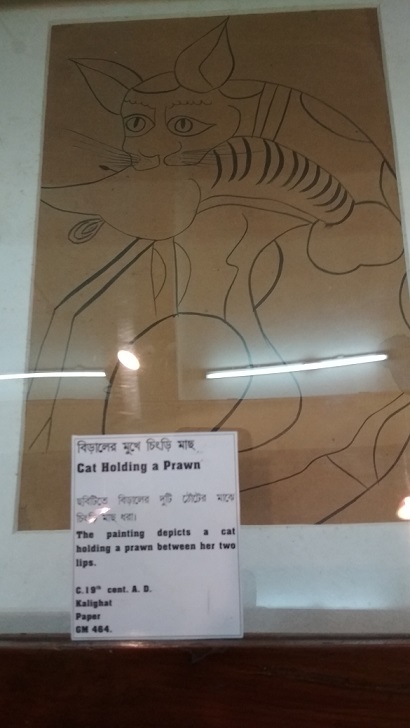

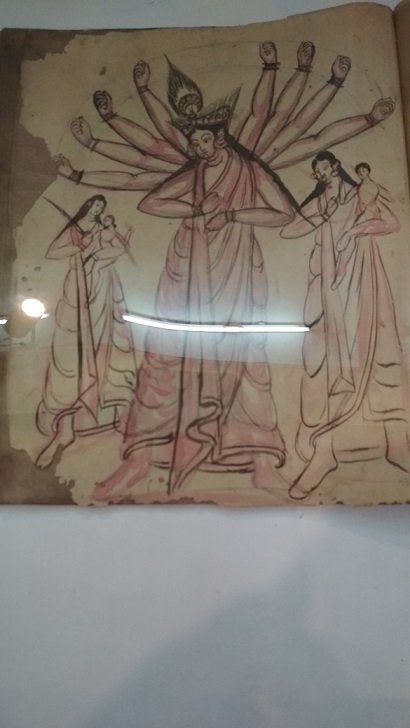

And it was the jarigan recordings of Arnold Bake which had taken me to the Gurusaday Museum, also because I became part of a campaign to save the museum from closure. There I was surrounded by the art, embroidery, dolls and toys and scroll paintings and musical instruments which awakened all my senses of sight, sound, touch, taste and smell.

Visit to Gurusaday Museum, Thakurpukur, Kolkata on 11 April 2019

Postscript

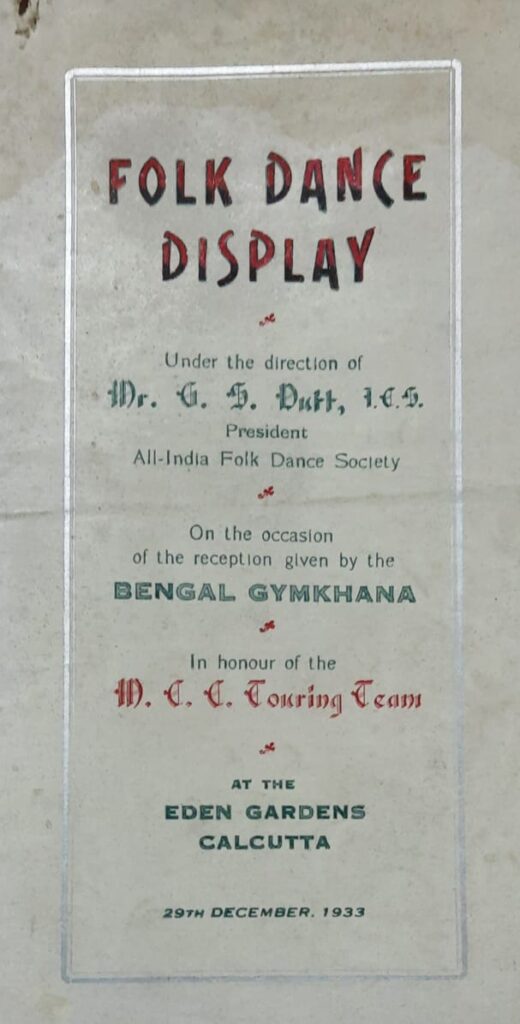

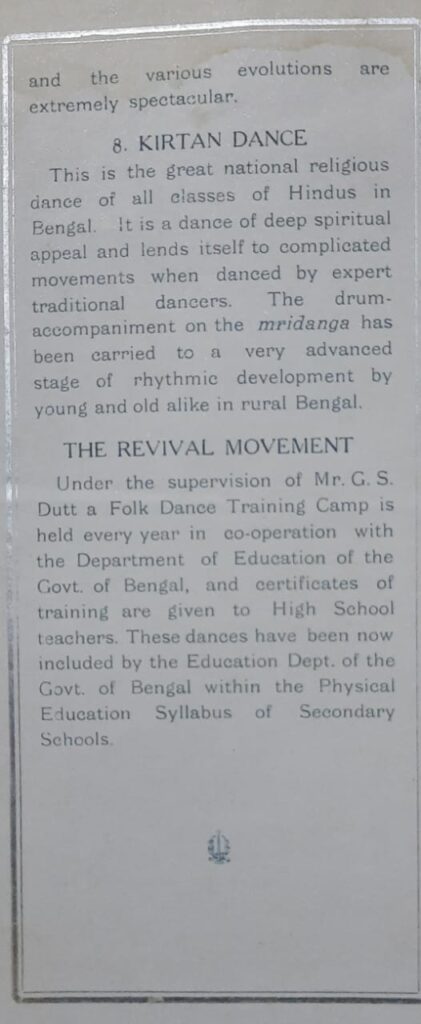

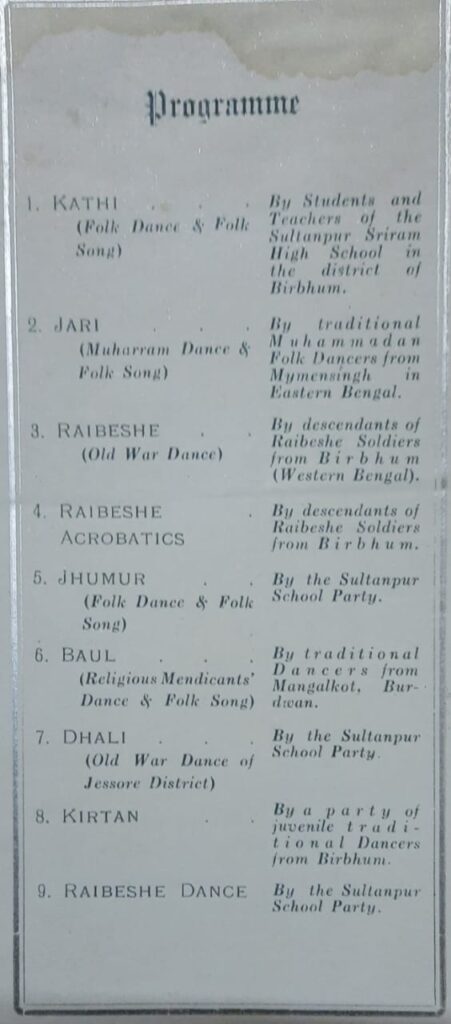

On 26 August 2022, Bratachari Nareshji sent me a Whatsapp message with some photos. The message read: এ গুলো দেখুন। “ফোক ডান্স ডিসপ্লে” র ফোল্ডার।১৯৩৩এ। মনে ছিল। খুঁজছিলাম অনেক।আজ হঠাৎই পেয়ে গেলাম। পুরাতন অনেক,-এই সংক্রান্ত-কাগজের মধ্যে। ঠিক আছে।ভাল থাকবেন। (See this. The folder of the ‘Folk Dance Display’ organised in 1933. I had this in mind, had searched hard. Suddenly I found it today, tucked inside some other related papers. Very old stuff. Anyway, take care.)

Once again, the archive open the door to other archives.

- Laksmisvar Sinha, a Doorway to Many Worlds

- Motru Sen and Jaya Tagore: From Image to Sound

- Mapara’s Cradle Song and Shruthi Vishwanath’s Response

- The Bauls of Kenduli in 1932

- Pinakin Trivedi and the Autograph Book

- Roof-Making Songs of Baori Women

- Listening to Savitiri Govind with Sumana Chandrasekhar

- From Ranjan Shaha to Kobiyal Akhtar Shah in Kasba, Birbhum

- Kusum, the Nachni and her Jhumur

- From Gurudayal Malik to Mohan Singh Khangura and Madangopal Singh