Roof-Making Songs of Baori Women

All that we get from the catalogue of Arnold Bake’s cylinders is that on 19 August 1933, he recorded a ‘Song of labour’ of some ‘Baori women working on the roof of the post office’, in Santiniketan. Their names, age and where they came from remains unrecorded, Bake only marked them by their caste and professional identity. In fact, the two go together in Birbhum—lower caste Boari women have traditionally worked as roof-makers and thus they have been singers of chhad-petanor gaan or roof-making songs. The cylinder number of this song was 254 of the Bake India II collection.

The words of this chhad-petanor gaan are hard to hear. This is a work song that the Baori women working on the roof of the post office, beating to make it smooth and flat were singing. Bake must have heard them singing and arranged to record them. The special character and power of such songs is in the sound of the voice melding with the sound of the work the singers are doing. However, the recording could surely not be made while the women were working and singing in unison, since he would need the singers to come close to the horn of his phonograph. Therefore, the recording we have from Arnold Bake could not have been the real sound of this music. The words are hard to hear, but there are details of social history held within the layers of this song. Bake did not make many recordings of work songs in Bengal (although songs such as the bhatiyali are also sung by fishermen or farmers, during work); however, he specifically recorded work songs in other places. For example, he recorded the Newari people’s rice-seeds-sowing and transplanting songs in Nepal (Bake India II/22-23), road-making song (Bake India II/61); lullaby in the Malabar coast of Quilon (Bake India II/159), fishermen’s songs in Travancore (Bake India II/152) or the plantation/cultivation song (Bake India II/158) or chaffing song (Bake India II/135) recorded in Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

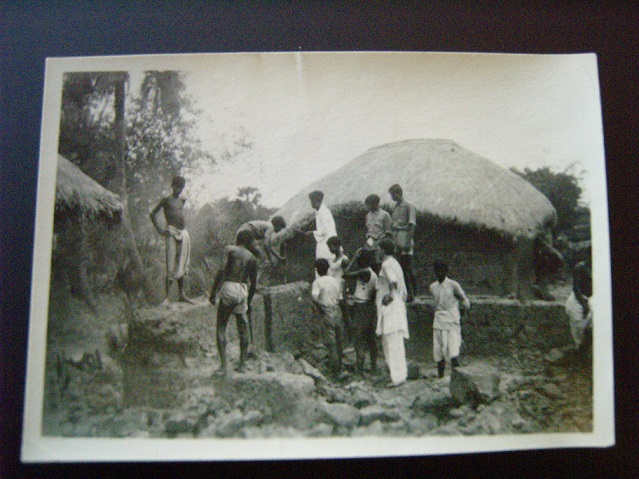

This photo is not from the recording session of course. But it creates an atmosphere and shows the kind of engagement Arnold Bake had with his surroundings; how he saw, felt and listened to things and kept records of some of his experiences. Source: Special Collections, Leiden University library. (Photo of photo, taken while working in the library in 2015)

Who might these nameless singers have been and what might this hard-to-listen-to song be all about? I have had many recordings from the archives, where the song lies buried under layers of noise of the machine, and the noise of the material on which the recording was made and under layers of dust and time. But when I have taken those songs to people who know, the results have been quite amazing. Those who know the songs or about the songs, they can hear things which we can’t. They hear even absent sounds. The real thing, therefore, is to find the ones who know.

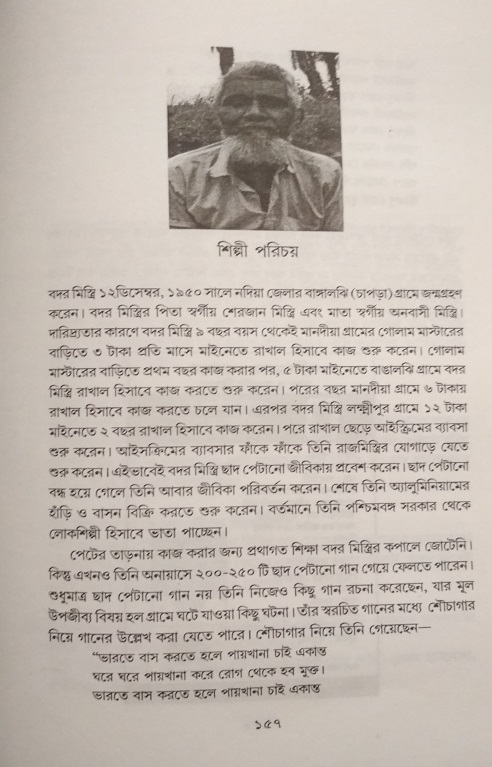

It was quite a matter of coincidence that Selim Mondal of Bangaljhi (Chapra) vilage, Nadia contacted me in 2020 to say he and his friends had compiled an anthology of chhad-petanor gaan, which they wanted to send to me. Edited by two friends Robiul Islam and Selim Mondal, and published by their own Tobuo Proyash, the book has a few short essays on roof-making songs in the context of work songs of Bengal, followed by an anthology of chhad-petanor gaan, collected from local singer and living archive of the genre, Badar Mistry, once a builder who made roofs but now does odd jobs. Mistry talked about the art and craft of roof-making, a tradition mostly lost now and sang many songs for Selim and Robiul. They recorded him on their phones. They had a hard time finding the right time and quiet place to make their recordings. Working like true archivists, Selim and Robiul recorded, transcribed and notated the songs. They then published the volume, while the songs remain in their folders. I am grateful that they shared two soundtracks with me.

The songs of Badar Mistry are nothing like the song Arnold Bake recorded. They are an assortment of tunes and styles—chatka, bhatiyali, something comic, some social commentary—they have a radio-like quality, things which go by the name of palligeeti, or a generic rural song. How can this be chhad-petanor gaan or roof-making song? I wonder. Then I think that perhaps a song becomes a chhad-petanor gaan at the time of its performance, during work. When a group of people sing these songs together, the lead and the chorus, the song is transformed. The rhythm of work gets built into the song, the steady beating of oars on the water (sarigaan), dhenki threshing the paddy (dhenkir gaan), wooden ‘pikni’ pounding the roof (chhad-petanor gaan)–whatever the work is, it makes the song.

If we listen to these workmen from Bangladeshi director Kamar Ahmad Simon’s 2012 film, Shunte Ki Pao! Are You Listening!, I think the point becomes clear.

Clip posted with kind permission of the filmmaker.

Without the chorus, without the action, how would this song be? We can try to imagine this. How would this song work as a solo piece, paced down, no collective breathing to create the rhythm, no action to give it its extra dimension and particular identity? How would it be if the singer was taken to a quiet place to sing to the recorder of a phone in order to keep a record of the song?

With such thoughts in mind, I tried a little experiment. I played Bake India II cylinder 254 on my laptop and tried to listen to it first on its own and then adding roof-beating sounds from a recent art installation of Sanchayan Ghosh.

The Bake recording is from the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, which I have had with me since 2016, when there was a plan to work together with them to produce an album. Having the recordings helped hugely in my fieldwork, even if the album could not be made. The song has also been made available for listening by the British Library as a ‘Song of labour’. The roof-making sound is from Sanchayan Ghosh’s work, Chhad Petanor Gaan, also available for free listening here.

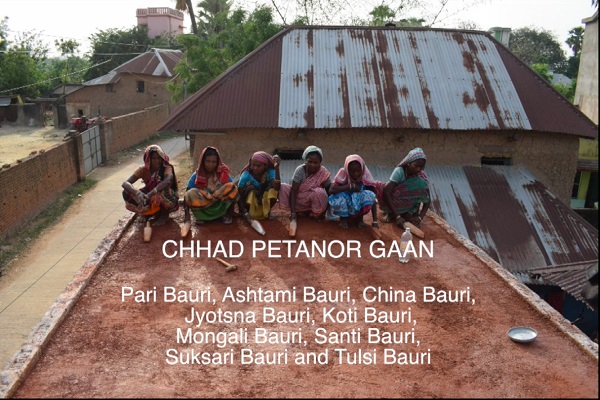

From 2016, Sachayan Ghosh, a visual artist and Associate Professor of Kala Bhavan, Visva Bharati, Santiniketan, started working with a group of Bauri (same as Arnold Bake’s Baori) women of Mohammad Bazar, Birbhum, to understand the now near obsolete process of making petano chad or roofs with brick dust, lime and molasses; the other ingredient of this roof is the song. Singing while rhythmically pounding the mortar to make it hard as betel nut was an integral part of this roof-making process, till concrete took over. The Baoris/Bauris are lower caste people and in Birbhum, traditionally, it is the community’s women who have built these roofs. Chhad petanor gaan, as Sanchayan writes in his book on this project which was published by Rhito, Kolkata, in 2020, ‘would often reflect observations and expressions of everyday life, about power, love, suffering, sexuality’ and so on.

From Sanchayan Ghosh’s video.

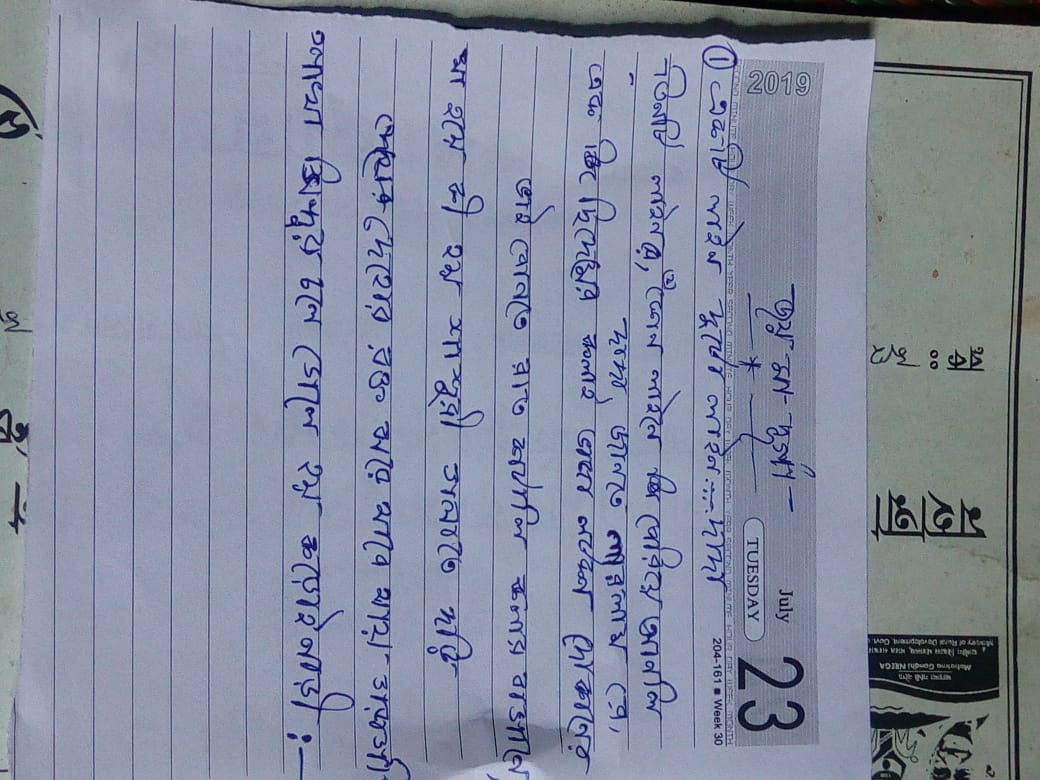

Although unnamed, Bake’s Baori women would be the same as Durga, Pari, China, Jyotsna, Koti, Mongoli, Santi, Suksari and Tulsi, with whom Sanchayan has worked. He organised an old-style roof-making in the village, and documented the process, while recording their songs. As I had shared my work with Sanchayan, he sent the Baori women’s work song from 1933 to his collaborators in Mohammad Bazar. At first, the women sent us some rough recordings. Pari Bauri is really their leader and she was not around during the first attempts made on 21 December 2021. Two days later, Pari, about 50 years old, sat down with some women, listened to the Bake recording and they sang a song. It is clear from the final recording that she could connect with the old song. They had recorded on their mobile phones on both days.

Recorded on 21 December 2020, Bauri women of Mohammad Bazar.

Led by Pari Bauri, recorded on 23 December 2020

Words of the song Pari Bauri and the other women sang. On close listening again to Bake’s recording, it seems we can hear similar words in the old song and the structure is certainly the same.

It might be interesting in this context to listen to a work song that the father-and-son ethnomusicologist team of John and Alan Lomax recorded in the Darrington State Prison Farm in Texas 1934. I found this freely downloadable song here and there is much more about work songs on the Library of Congress website. ‘Long John’ was sung by a man identified as ‘Lightning’ and a group of fellow black convicts. ‘Black prisoners working in gangs to break rocks and clear swamps relied on the repeated rhythms and chants of work songs (originating in the forced gang labour of slavery) to set the pace for their collective labour. Long John mixed religious and secular concerns, including the notion of successful escape from bondage, a deeply felt desire of both slaves and prisoners.’

- Laksmisvar Sinha, a Doorway to Many Worlds

- Imam Bux Boyati of Mymensingh at Gurusaday Dutt’s Suri Mela

- Motru Sen and Jaya Tagore: From Image to Sound

- Mapara’s Cradle Song and Shruthi Vishwanath’s Response

- The Bauls of Kenduli in 1932

- Pinakin Trivedi and the Autograph Book

- Listening to Savitiri Govind with Sumana Chandrasekhar

- From Ranjan Shaha to Kobiyal Akhtar Shah in Kasba, Birbhum

- Kusum, the Nachni and her Jhumur

- From Gurudayal Malik to Mohan Singh Khangura and Madangopal Singh