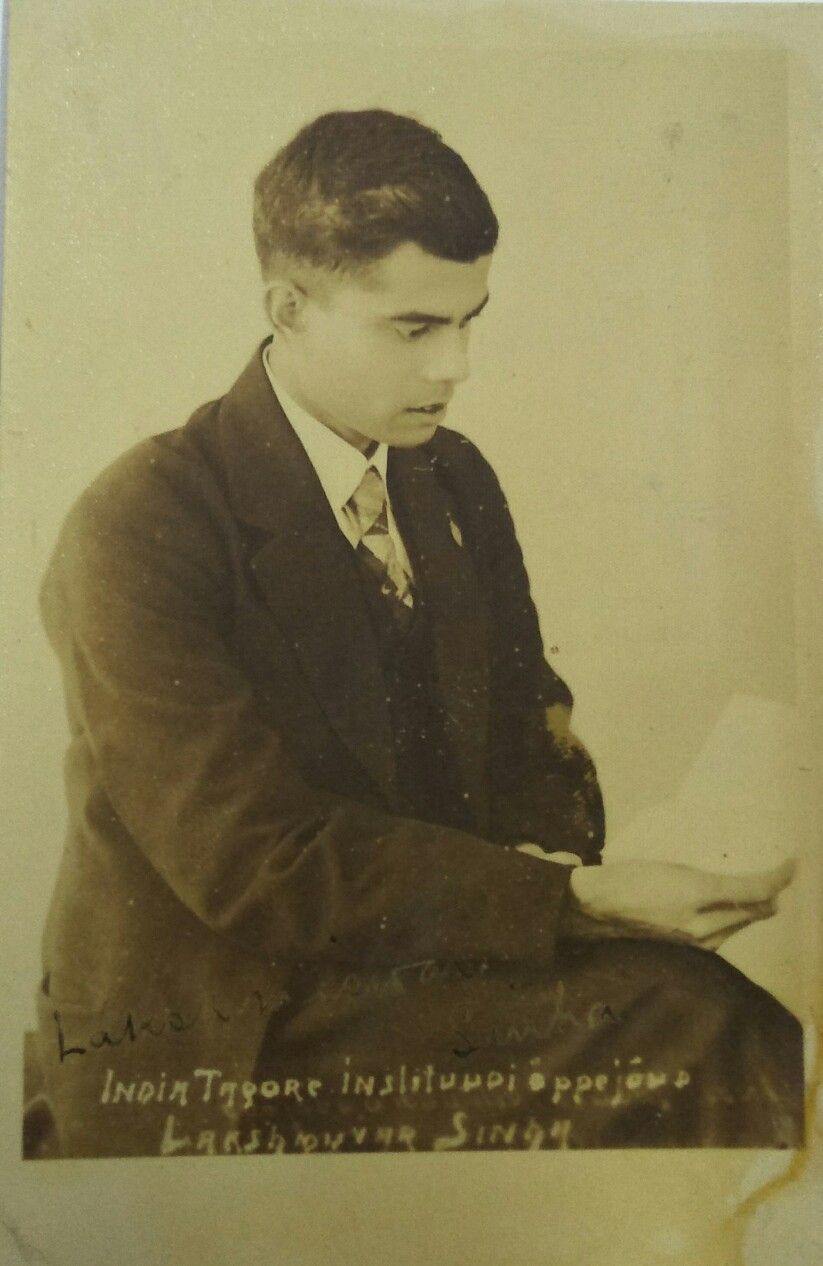

Laksmisvar Sinha, a Doorway to Many Worlds

It is hard to sum up in one sub-chapter the life-story of Laksmisvar Sinha (1905-1977) and my many stories of looking for, and finding him, in many places. He should be a book, a film; he can be many things.

The spelling of his name that I have used is the spelling on Arnold Bake’s catalogue. He might have written his name as Lakshmiswar Sinha, because that is the spelling on his autobiography, in Esperanto.

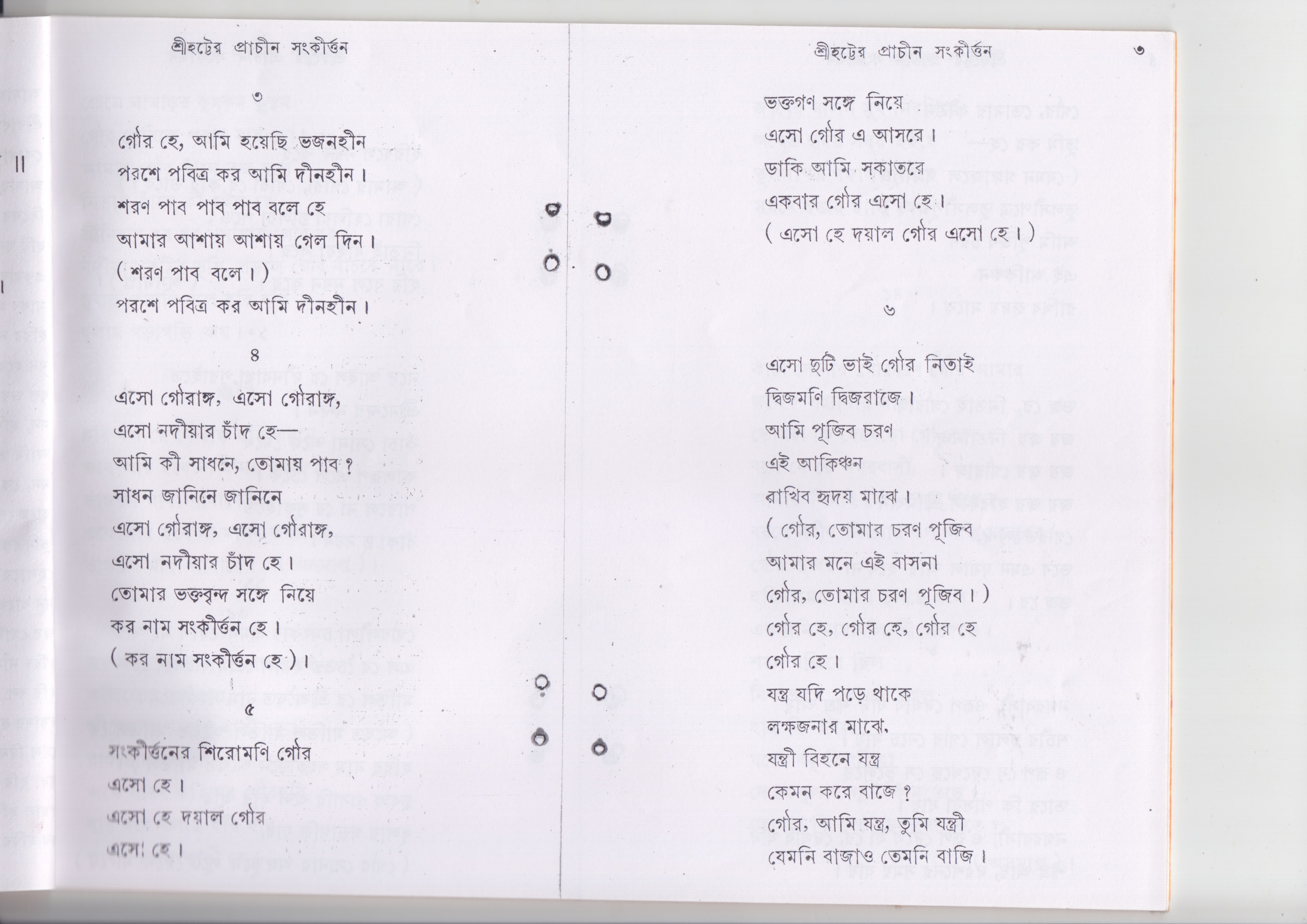

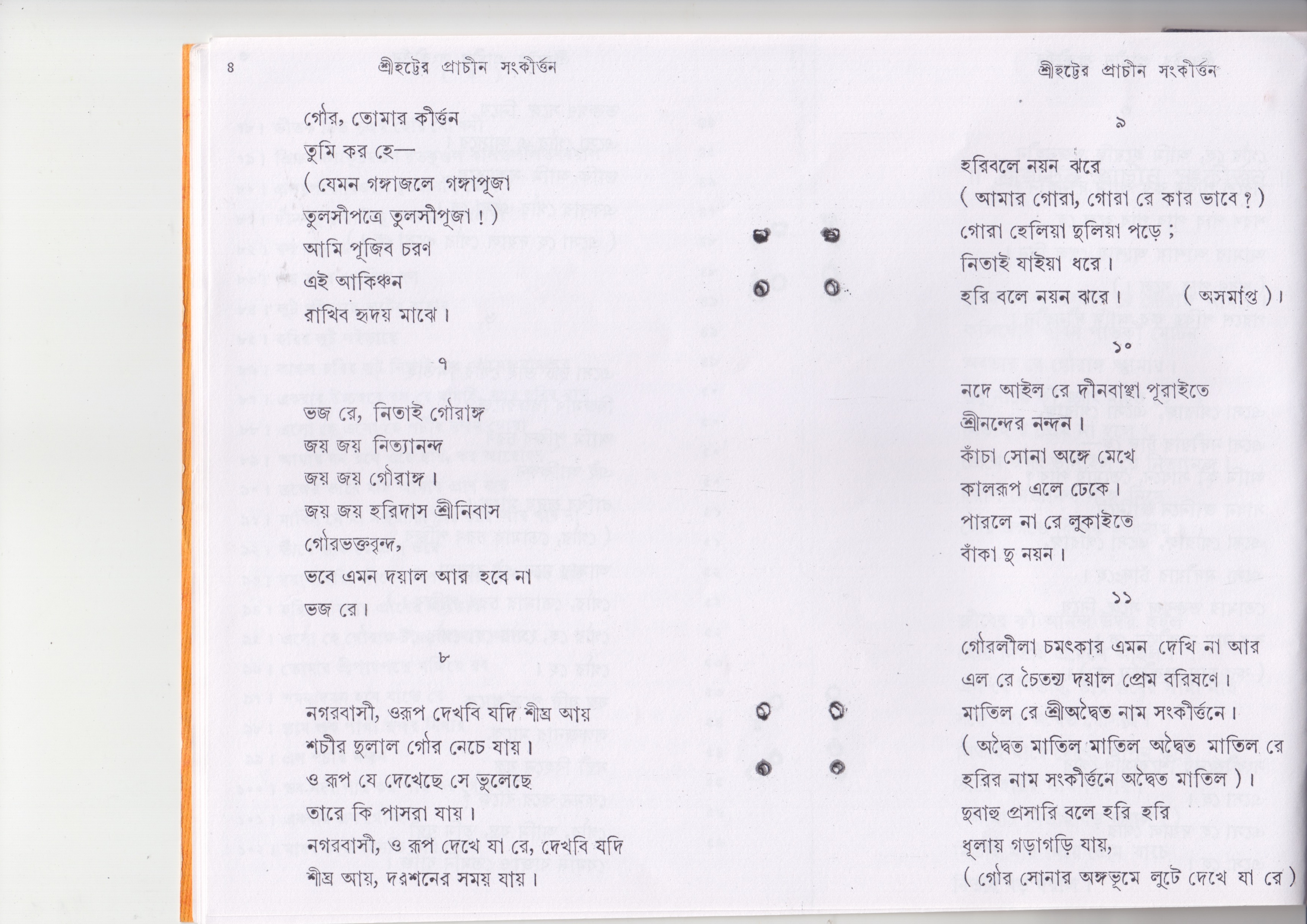

There are many versions of this catalogue with various archives which house Arnold Bake’s work. This is the original list, collectively produced by various scholars including Alistair Dick, based on Bake’s own papers. As scholars have worked on the cylinders, the notes have been revised. I have the same pages from the British Library, the ARCE, Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv and also what was shared by Amy Catlin-Jairazbhoy; therefore, the same list must be with UCLA too.

The British Library and the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv’s catalogues had the following description for Bake India II, cylinder 245: ‘Assamese folk songs sung by Laksmisvar Sinha [recorded at] Santiniketan 16/4/’33 a. folk song from Sylhet b. village song Hari sankirtan’ (there are two songs on the cylinder). Assamese folk songs, but from a village in Sylhet? That got me thinking. When I listened, they were Bengali songs, not Assamese. This is what had initially drawn my attention. What then could Assamese mean in this context? It wasn’t too difficult a question. Bake must have written Assamese because Sylhet was part of Assam in the 1930s when he met Laksmisvar. In fact, from the time of the arrival of the British to the region in the mid-eighteenth century, right upto 1947 when it went to East Pakistan, Sylhet has swung between Assam and Bengal, belonging to one, then the other, back and forth. Then in 1971, when the nation of Bangladesh was born, it assumed another identity. It has a special place within Bangladesh too, for it is from here that large numbers of people have scattered to all regions of the globe, with a large diaspora in the UK. Besides, the Sylheti people of Cachar in Assam are geopolitically Indian, even partly Assamese in identity, but distinctively Sylheti too. Hence, when Arnold Bake recorded Laksmisvar Sinha’s songs in 1933, he wrote Assamese as a geopolitical marker and not a linguistic one. He did not record the name of Sinha’s village.

(Interestingly, the British Library catalogue has been revised from the time I first came across the above note around 2013, and in the latest version, the word Assamese has been erased. That to my mind has led to a kind of erasure of history. How to revise archival metadata but also also retain old traces?)

From 2015, owing to The Travelling Archive in East London exhibition when the British Library gave us copies of the recordings we requisitioned for display at the exhibition, and which anyway got copied on our own computers, I began to carry the Arnold Bake recordings wherever I went, and any occasion I got, I played the songs to those who might know something. After the Santiniketan exhibition in 2016, when the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv gave us copies of a whole set of the Bake cylinders from Bengal as part of an unfinished collaboration, I had more recordings to journey with. Of course, the first few copies of Bake’s recordings that I had were given to me by the Archives and Research Center for Ethnomusicology, Gurgaon, when The Travelling Archive website was being launched in 2011. Therefore, on a visit to Sylhet in 2018, I thought of playing the songs of Laksmisvar Sinha to Ambarish Datta, my friend and guide in matters relating to Sylhet.

Ambarish Datta in his home on 18 January 2018. He comes from a Hindu Vaishnava family of musicians; his father, Anil Kumar Datta, was a well-known kirtan singer. Ambarishda has deep local knowledge about the varied cultural and spiritual traditions of Sylhet. I have travelled in the field with him on so many occasions, since 2006. Here he is surrounded by pages from his father’s handwritten anthology of songs.

In January 2018, I was in Sylhet to follow up on the sailors’ songs that Bake had recorded in 1934. On both 16 and 17 January, Ambarishda and I were moving around on the trail of the sailors. The following day, in Ambarishda’s home, we spent the evening talking about things. I wanted to also know about Ambarishda’s father and the kind of kirtan they sang in their home, at akhras and ashors (communities of Vaishnava singers and devotees). He told me stories about the teachers his father had, the types of kirtan they used to sing, the difference between the kirtan of West Bengal and that of Sylhet (‘Palit babu used to sing Pashchimbangiyo Manoharshahi kirtan’). He was touching upon questions of class and caste, and religion too, but it was all happening in the natural flow of the conversation. ‘There were Bijit Chowdhury, Harendra Bagchi, Dinen Saha of Kushtia, all of whom sang kirtan in Sylhet. There used to be a singer from Chandpur who used to come. Khol and kartal were the main accompanying instruments. Then there was Nader Chand Khan who played the sitar, esraj, flute and many other instruments, and whom I remember accompanying my father; by then he was an old man. Nader Chand’s home was in Brahmanbaria, and he came from the family of the famous Allauddin Khan. He had a Muslim name, but before Partition he played in the court and temple of the Hindu raja of Tripura. They had problems with someone with a Muslim name playing their religious music, which is why he took the name Nader Chand (নদের চাঁদ another name for Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu). He came over to Pakistan after 1947.’ Thus, tales were spun that evening, weaving myth with memory, while Ambarishda broke into song from time to time, remembering songs his father had taught him. The session however had started with me playing Laksmisvar Sinha’s cylinder recordings to Ambarishda. My Zoom H4N-recorder had developed a problem at this time and we can hear a constant noise in the recording.

Ambarish Datta and I talk in his home in the Uposhohor area of Sylhet town on 18 January 2018

With Arnold Bake’s Santiniketan recordings, just as they represent a range of sounds, experiences and histories, it is interesting how diverse my journey following those sounds has been. For some of the recordings, the sounds constitute a world of Santiniketan where the continuity from Bake’s time to the present remains unbroken. Which is why it was possible to easily meet people such as Kshitimohan Sen’s grandson or Indira Debi’s grand-nephew or Jaya Sen’s daughter and granddaughter. For some such as, say, G. Mapara, the sounds led to a lot of speculation, which had nothing to do with Santiniketan. With Pinakin Trivedi, the songs led to a whole rich Santiniketan archive kept with the family, but there is no memory of the man within Santiniketan and no awareness about his personal archive. Savitri Govind’s story is recorded in some memoirs and the recordings of her songs remain, especially because her story is woven with the birth of some iconic Tagore songs. But she is more material for musicological analysis than family history. Even if we think of all of them–including Gurudayal Mallik–as some kind of ‘outsider-visitors’ to asram, pulled in by the name and charm of Tagore, Laksmisvar Sinha had a far more sustained relationship with the place, built over a lifetime. He brought so much to Visva Bharati in the shape of manual work-based pedagogy and weaving patterns, taught there and lived on campus till the end of his life. Yet to find him, I had to begin my journey from his ancestral home, a place he had left a long time ago. Later I also found some of his traces in—rather, around—Santiniketan.

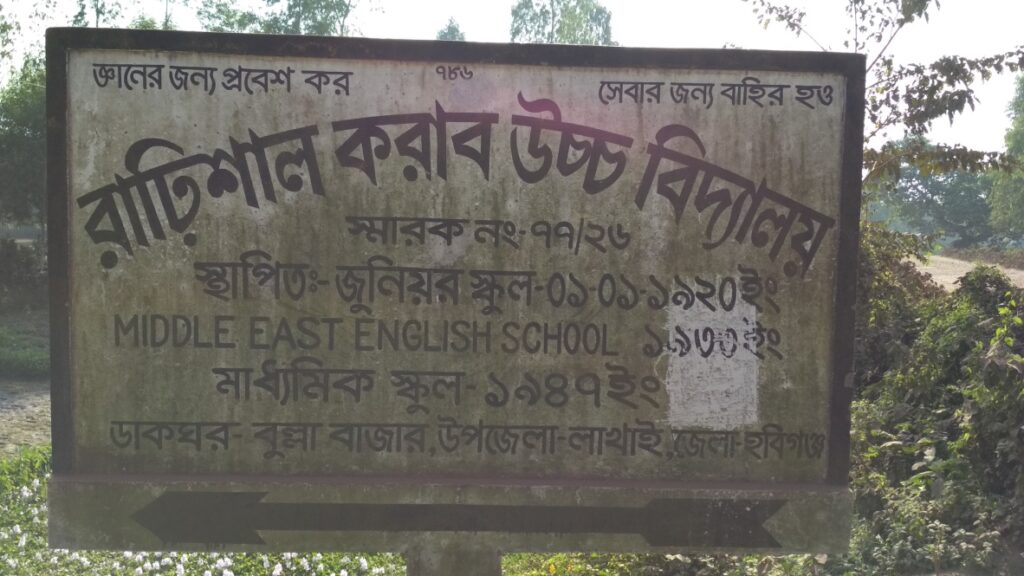

A signboard in Rarishal village. Photo taken by me during my visit in November 2018.

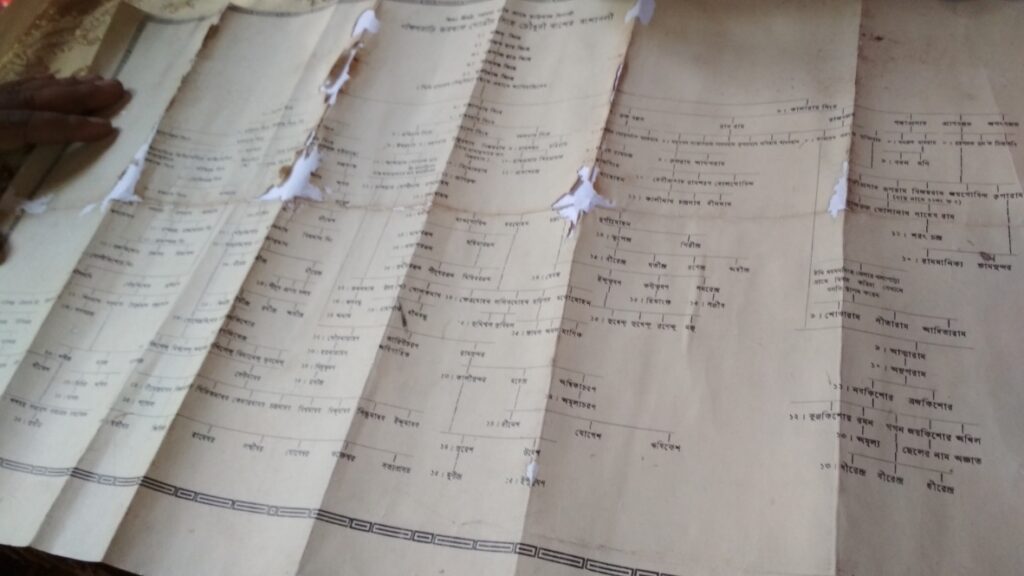

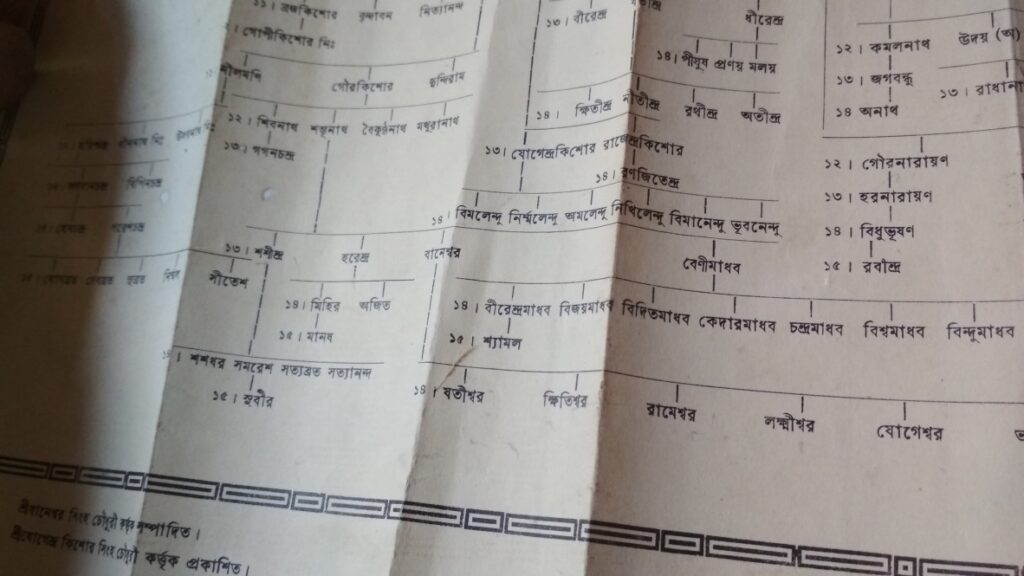

The songs I had played to Ambarish Datta in January 2018 had stayed with him and towards the middle of the year, he sent me a message to say that he had been able to locate the family of Laksmisvar Sinha. In November 2018, I went back to Sylhet and with Ambarishda went to Rarishal, the village in Habiganj district which used to be the home of Laksmisvar. The name Rarishal is interesting as the Sinhas had gone to Sylhet from the Rarh region in the west of Bengal in search of fortunes and gradually became rich and powerful landowners in this village in the far east of Bengal (Rarhishal is a more accurate spelling, but since the official spelling in Bangladesh is Rarishal, I am sticking to it.). I went there on 19 November 2018 and met Laksmisvar Sinha’s extended family—that branch which never left the village, and don’t intend to either, while many did at various points of time, especially after Partition in 1947 and the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971. Those I met had never seen Laksmisvar. The oldest person I met, 68 at the time, Dilip Sinha Chowdhury, was a distant nephew. He said he had heard Laksmisvar Sinha’s stories from the latter’s brother, Jogeswar, who had remained in the village for much longer. They said there was a songbook in which Laksmisvar Sinha had written down many of the kirtans they sang in their family—they could not find it while we were there and haven’t found it yet. I often send messages to Bappi (Sanjit Sinha Chowdhury), a young man who would be some great grand nephew of Laksmisvar, and ask him to look for the book. Bappi does political theatre, and goes by the name of Bappi Sramik (Worker Bappi) on Facebook. Each time I ask, he politely says, ‘I am looking Didi.’ They are all perfectly aware of the rich history and heritage of their family and when we went, they showed us a family tree going back some fourteen generations. I played them Laksmisvar Sinha’s songs and made recordings as they listened and sang.

The family tree

A piece of an old wall in Rarishal. The year of construction and name of the head mason is inscribed. In 1335 BS (1928 CE) Sri Abid Mian of Maijdee, Noakhali had worked as a ‘rajmistri’ for the Sinhas. I think of Laksmisvar Sinha. 1928 is when he is sent to Naas in Sweden by Rabindranath Tagore to study the Sloyd system of handicraft; something he will bring into the pedagogy of Visva Bharati in 1932. Around 1934-35, two Swedish women will come to Santiniketan to teach in the Sloyd system: one, Miss Inga Jeanson and the other Miss Aina Cerderblom.

Dilip Sinha, Bappi and another young singer of Sylhet who had come to meet us in Rarishal, Ashim Kumar Das, listen to Laksmisvar singing ‘Dinobondhu kripasindhu’, Bake India II, cylinder 246

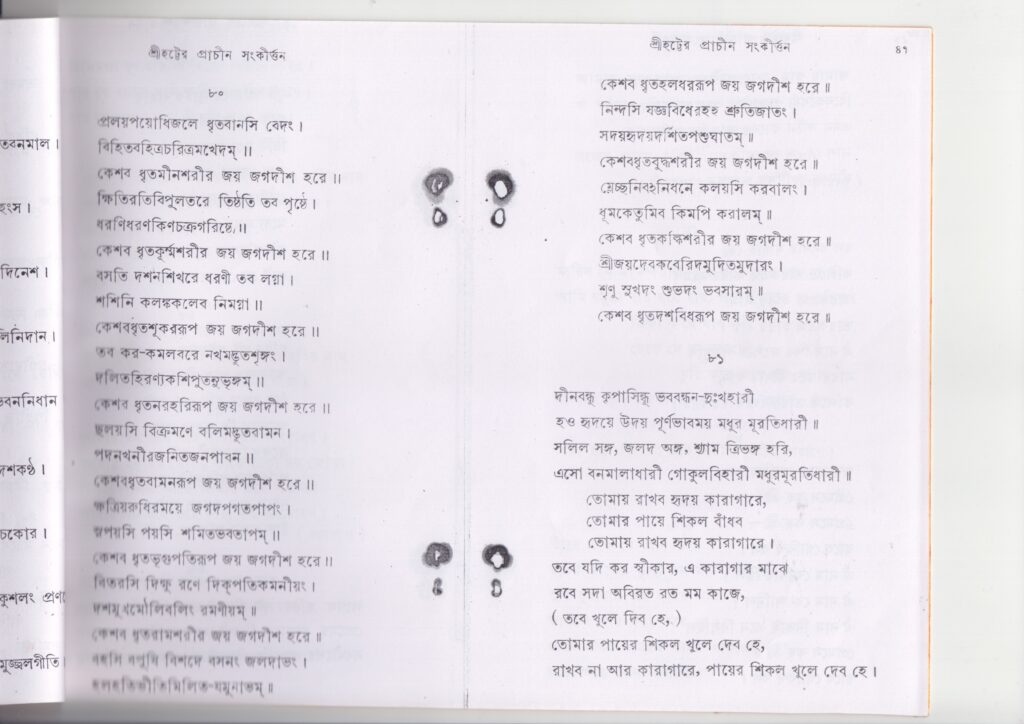

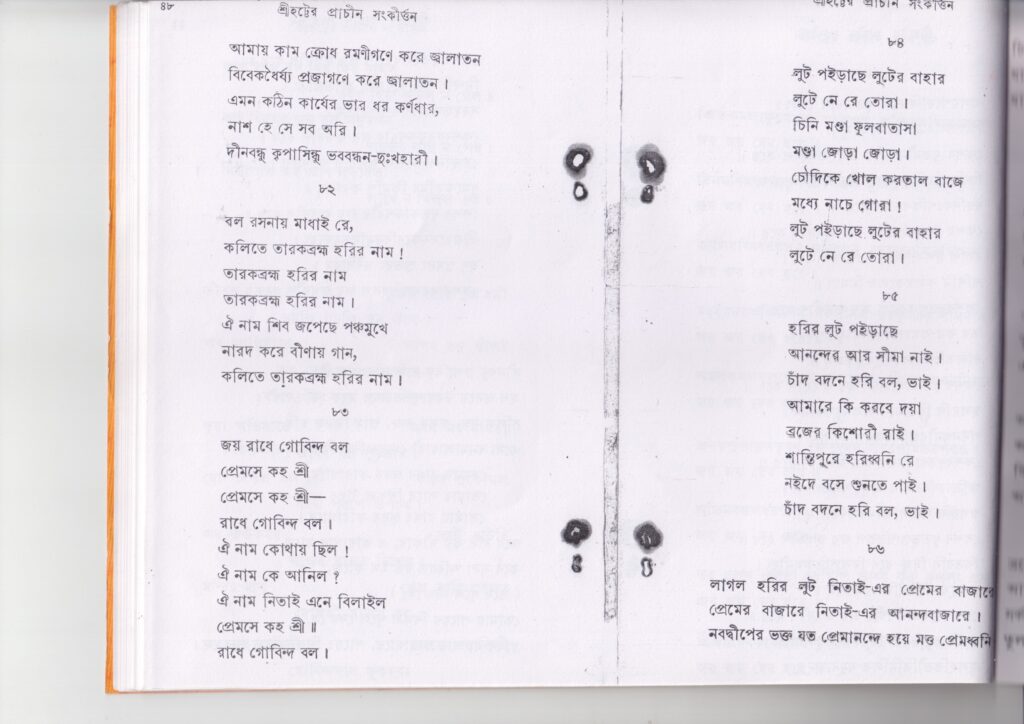

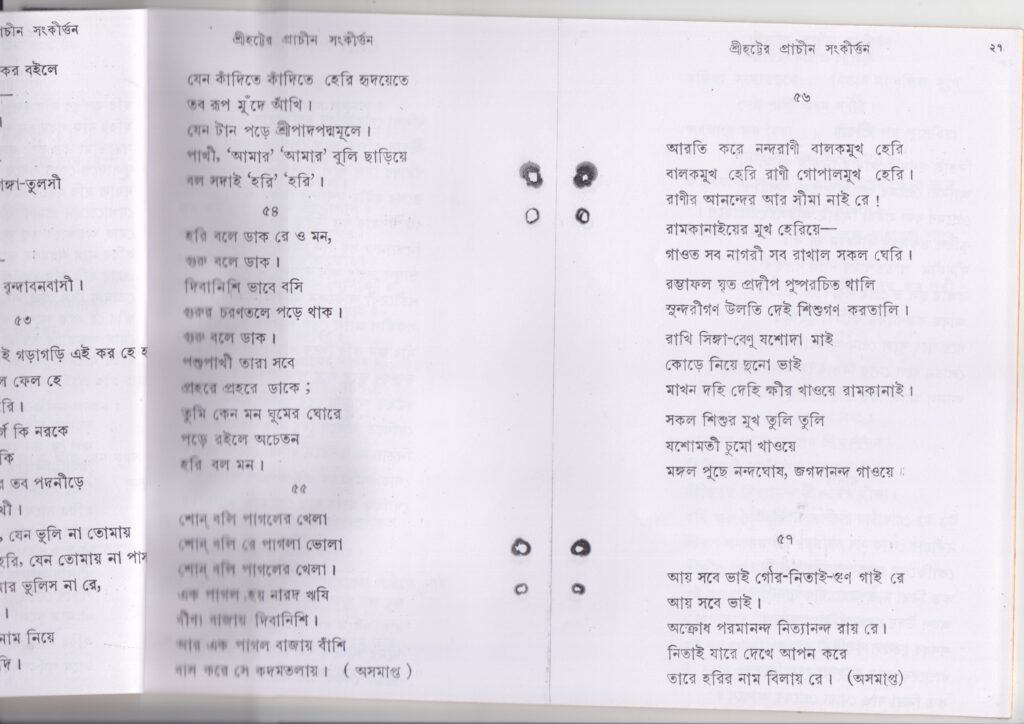

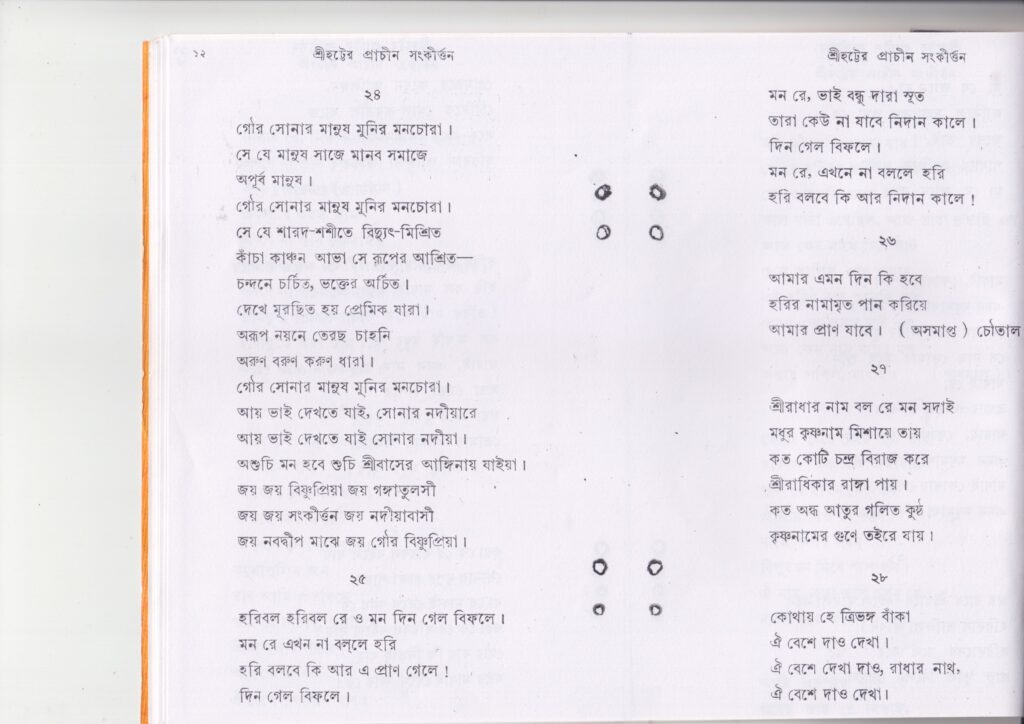

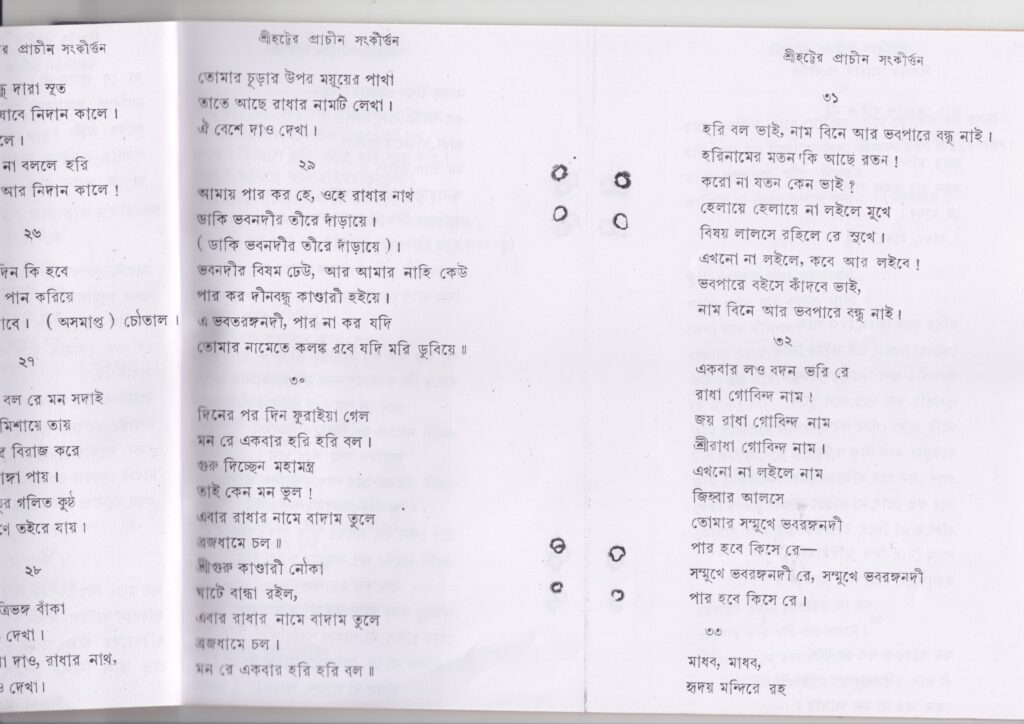

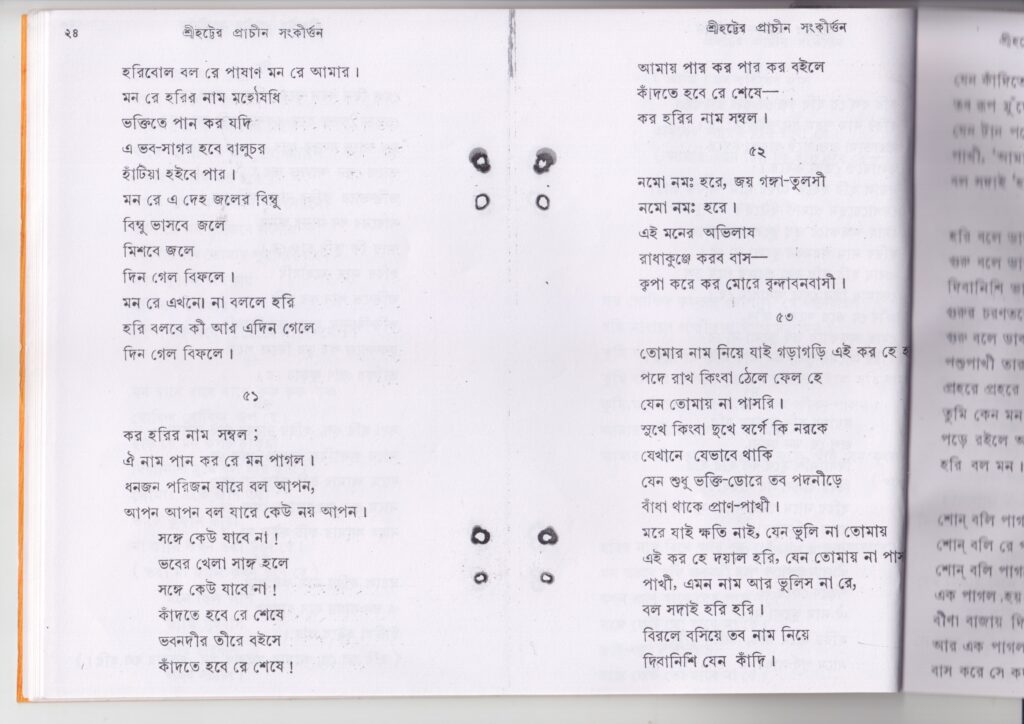

Pages from Laksmisvar Sinha’s anthology of kirtan from Sylhet, Srihatter Prachin Sankirtan, published in 1963. The song ‘Dinobondhu kripasindhu’ is part of the anthology.

Gour Sonar Manush. Dilip Sinha, Bappi and others listen to Laksmisvar’s recording, the second song of Bake India II, cylinder 245 . ‘We still sing this song,’ Dilip Sinha Chowdhury says. I request him to sing it for us.

Within the Sinha clan, Dilip Sinha Chowdhury is a nephew of Laksmisvar Sinha’s. He sings some of the songs Laksmisvar sang for Arnold Bake and talks about the Sinha family, their history and the days of the Liberation War in 1971.

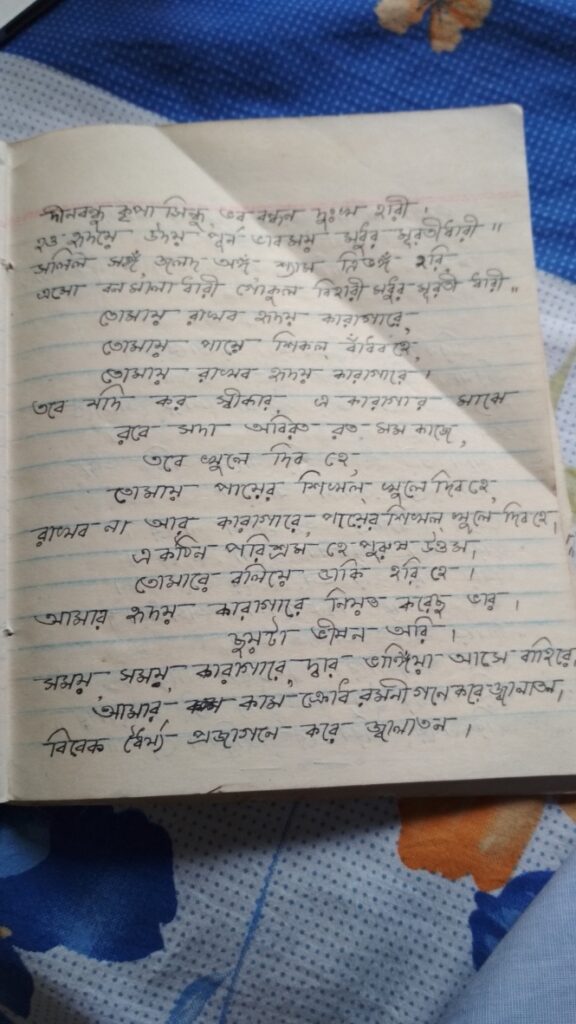

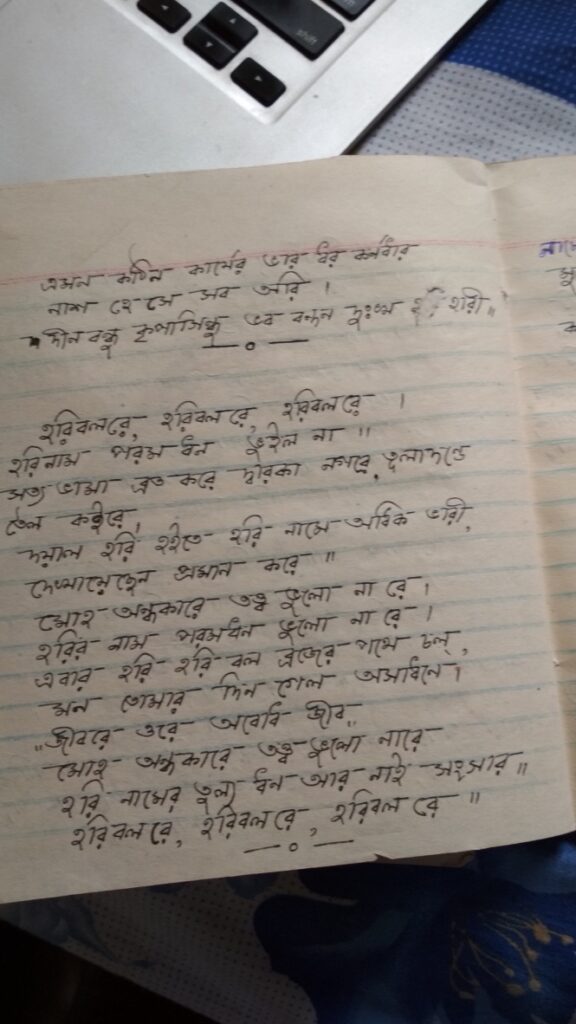

Pages from Dilip Sinha Chowdhury’s handwritten songbook, in which some of the songs Laksmisvar sang for Bake are also written.

Ashim Kumar Das of Dhirai, Sunamganj, comes from a family of performing artistes. This track is from Habiganj bus station where Ambarish Datta and I had gone from Sylhet and where Bappi and Ashim had come to meet us. We went to Rarishal village by a three-wheeler CNG, while Ashim went with Bappi on his bike. I am chatting with Ashim and he is talking about his parents, both of whom are jatra (folk theatre) artistes.

Turns out Ashim is a beautiful singer. He was very quiet throughout our interactions in the Sinha house, and then came a point when it became clear he was a singer. And, he sang so beautifully. Here are three songs; the Lalon song right at the end was quite unlike how Lalon Shah’s songs are usually sung, especially in the western side of Bengal, including Kushtia, Nadia and Birbhum-Barddhaman. I am also keeping that one here, to show a trend, because Ashim is not alone in what he is doing with the song. His take sounds ‘adhunik’—pop and filmy. He says he learned this song from a record of Shafi Mondol.

Once I had written a Facebook post on Laksmisvar Sinha in Bangla and I feel tempted to add an extract from that text here, because some things are so hard to translate. So here is a little bit in Bangla for those who will be able to get the রস (rasa) of the language. We will go to the story of Laksmisvar Sinha’s daughter and his books after this.

আদিতে ধ্বনি ছিল। In the beginning was sound. আমার বহু গল্পই শুরু হয় সুর শব্দ থেকে।

হল্যান্ডের সেই সাহেব আর্নল্ড বাকে, যাঁর কথা আমি মাঝে মাঝেই বলে থাকি, তিনি ১৯৩৩-এ শান্তিনিকেতনে লক্ষ্মীশ্বর সিংহ নামের এক যুবকের গান রেকর্ড করেছিলেন। নোটে লেখা ছিল, Assamese folk songs sung by Laksmisvar Sinha [recorded at] Santiniketan 16/4/’33 a. folk song from Sylhet b. village song Hari sankirtan. (এখন পরিমার্জিত ক্যাটালগ থেকে আসাম শব্দটি বাদ গেছে, এবং তার ফলে একটুকরো ইতিহাসও বাদ গেছে)।

লক্ষ্মীশ্বরের বাড়ি কোথায় ছিল বাকে লিখে যাননি, হয়তো জানতেনও না। আমার সিলেটের বন্ধুরা খুঁজেপেতে জেনে দিলেন। তাঁদের সম্পন্ন ঘর ছিল, তাই হদিশ মিলেছে অপেক্ষাকৃত সহজে। কিন্তু, কে জানতো যে সেই ১৯২০ নাগাদ সিলেটের হবিগঞ্জের রাঢ়িশাল থেকে পথের টানে বেরিয়ে পড়া একটি ছেলের গলার সুর ধরে প্রায় ৮৫ বছর পর অম্বরীষদা আর আমি ২০১৮’র এক শীতের দুপুরে তার কোন কালে ফেলে যাওয়া বাড়ির দাওয়ায় গিয়ে হাজির হবো? কে জানতো যে লক্ষ্মীশ্বরের সেই উত্তরপুরুষ (সরাসরি নয়, তবে জ্ঞাতিগুষ্টির ব্যাপার এই সব), যে আমাদের এত আদর যত্ন করে নিয়ে যাবে তাদের বাড়িতে, সেই গ্রুপ থিয়েটর করা যুবকটির দেয়া নাম সঞ্জিত সিংহ চৌধুরী হলেও, নেয়া নাম হবে বাপ্পী শ্রমিক? সে ঘুরতে ঘুরতে দেখাতে থাকে আমাদের–ওই যে লঙ্কার ক্ষেত, ওটা লক্ষ্মীশ্বর, আর ওই যে তার পাশের জমি, ওটা … ভাগ হওয়া পরিবারের ভাগ হওয়া পূর্বপুরুষের নাম বলতে থাকে বাপ্পী।

এক রকমের বাঙালি বাড়ির দেয়াল জুড়ে বিগ্রহের ছবি, রবীন্দ্রনাথ থেকে শেখ মুজিব, তারই মাঝখানে চে, আবার এক দেয়ালে সত্যজিৎ রায়, পাশে বাপ্পীর বাবার মুক্তিযোদ্ধার স্বীকৃতি পাবার ছবি, অন্য দেয়ালে শামসুর রহমানের কবিতার লাইন: ‘তোমাকে পাওয়ার জন্যে, হে স্বাধীনতা,…/তোমাকে পাওয়ার জন্যে/আর কতবার ভাসতে হবে রক্তগঙ্গায়?’

এহেন বাড়ির উঠোনে শুকোনো গামছার লাল রং আমাদের এক মৃত্যুহীন স্বপ্নের সাধের কথা মনে করিয়ে দেয়।

Inside the Sinha home in Rarishal and the courtyard, 2018

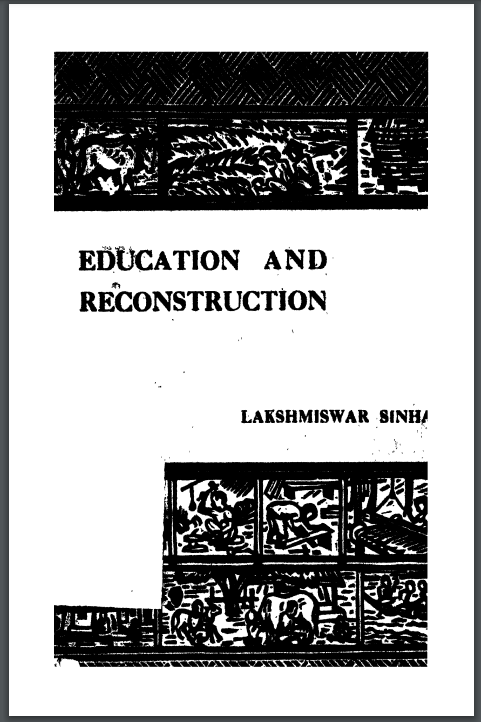

বাপ্পী ‘শ্রমিক’ থেকে লক্ষ্মীশ্বরের দিকে ফিরে যাই। দেখি, ১৯২৫-এ বিশ্বভারতী-গ্রন্থালয় থেকে ‘কাঠের কাজ’ বলে একটি বই ছাপা হয়েছিল। ভূমিকায় রবীন্দ্রনাথ লিখেছিলেন, ‘শ্রীযুক্ত লক্ষ্মীশ্বর সিংহ “কাঠের কাজ” বইখানি লিখিয়াছেন; ভদ্রলোকের ভয়ে “ছুতারের কাজ” লিখিতে পারেন নাই’!

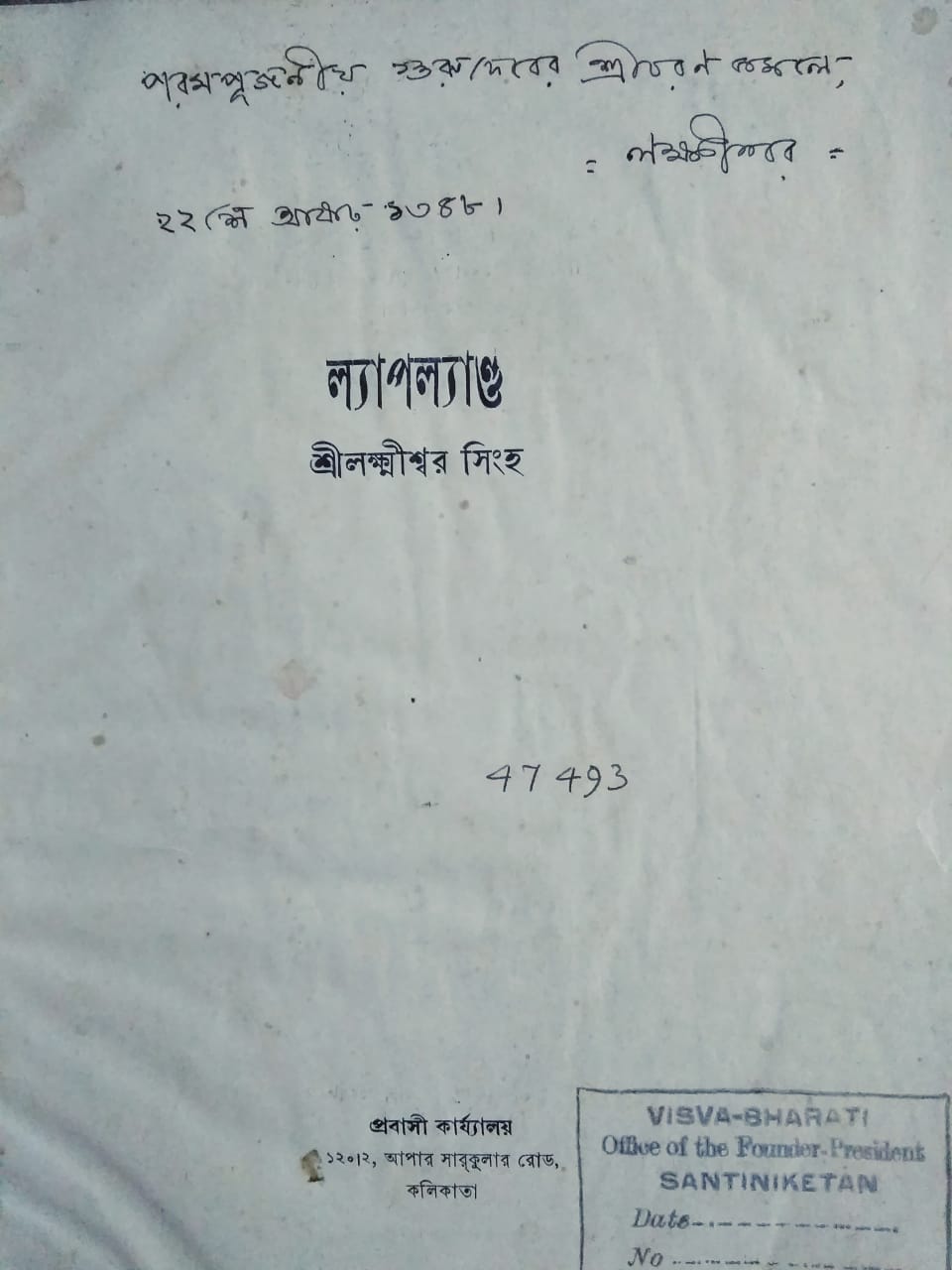

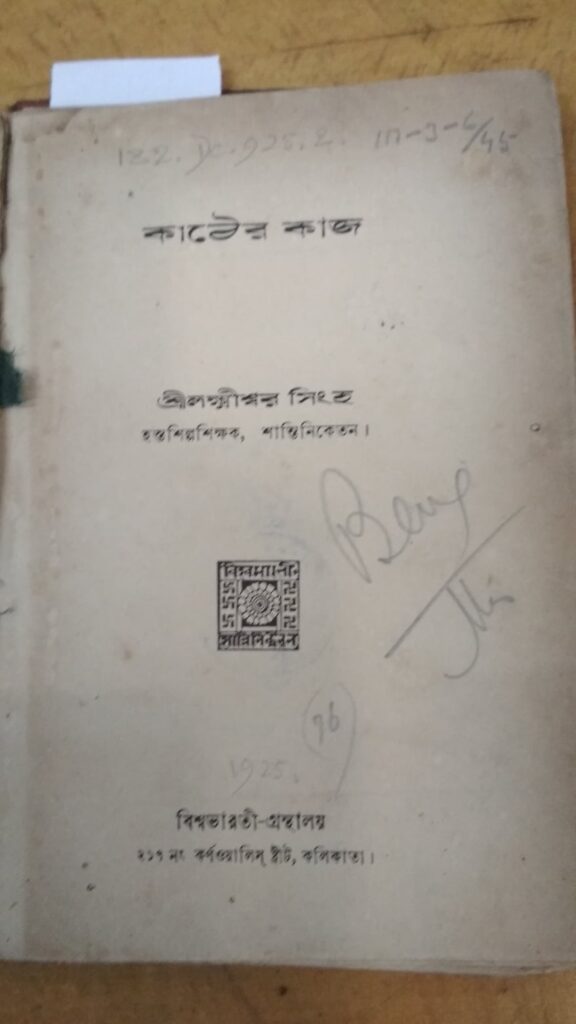

Laksmisvar Sinha’s book on carpentry, Kather Kaj, published by Visva Bharati Granthalaya in 1925

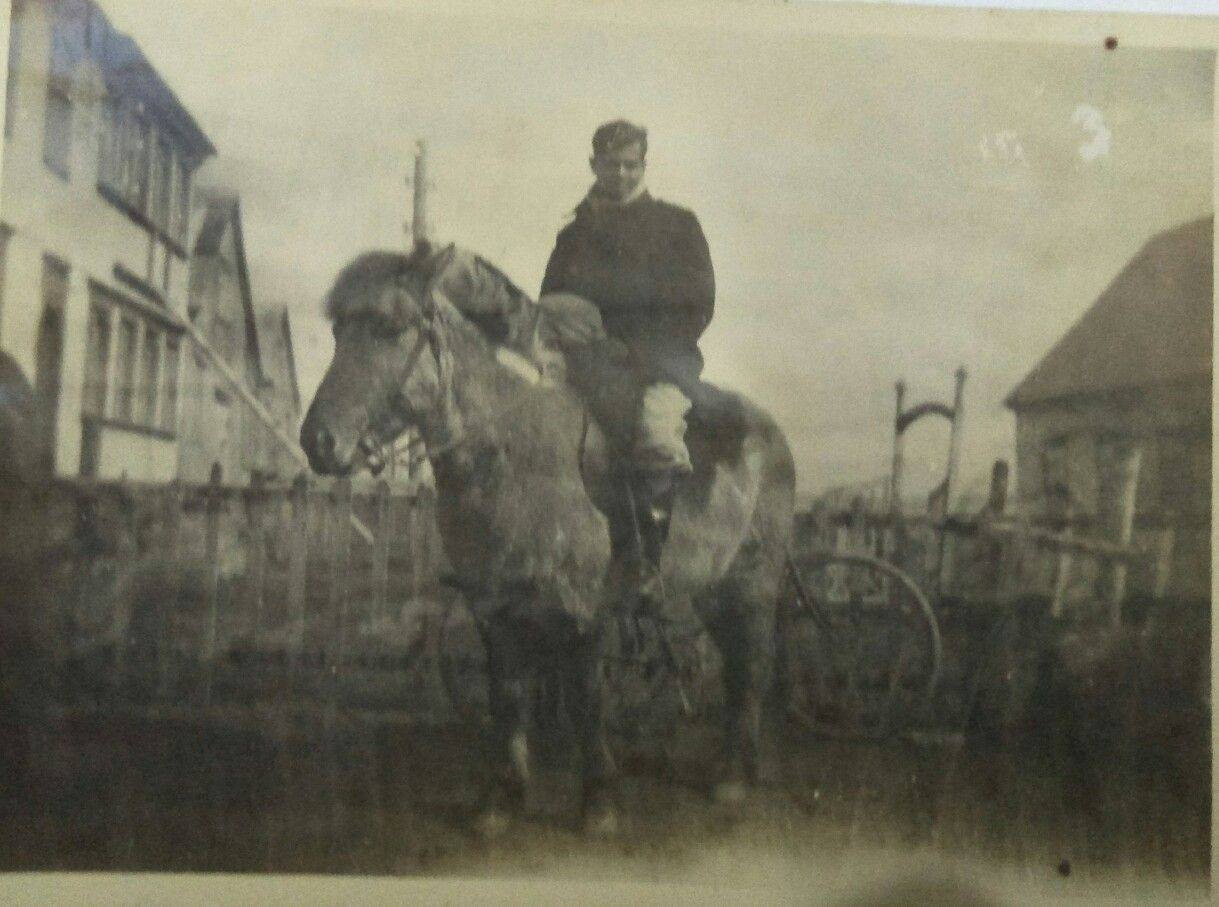

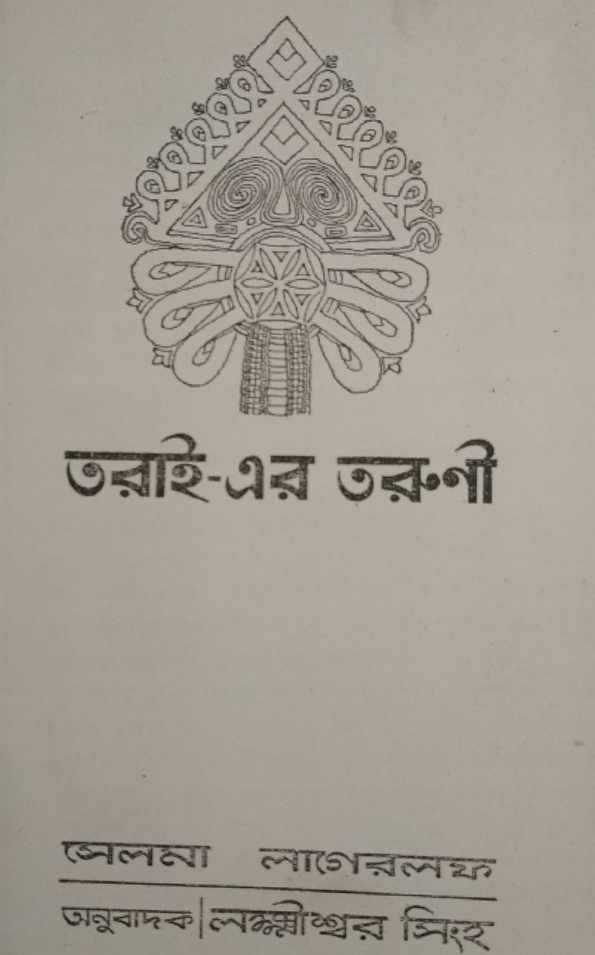

After the trip to Rarishal, I went on another trip to Santiniketan in April 2019, to follow up on some of the work I had done the previous year, mainly around the recordings of Pinakin Trivedi. It is then, just by chance, while talking with Bithika Mukherjee, whose husband, Nabakumar Mukherjee (1930-2015) had set up the Elmhirst Institute of Community Studies , that I came to know the whereabouts of Laksmisvar Sinha’s younger daughter Sumitra (born 1942). Nabakumar Mukherjee had worked in the Rural Reconstruction Centre of Sriniketan, Visva Bharati and had been taught by Laksmisvar Sinha. So, I met Sumitra Sinha on 28 April 2019 in a place called Banalakshmi near Santiniketan with a history of its own. Sumitra Sinha, quite infirm now, had no idea there could be a recording of her father’s voice from long before her birth, when he was a young man. As expected, she was truly overwhelmed to listen to his songs. She began to talk about her father, brought out old photos, talked about her elder sister who lives in Sweden, about their mother, and about songs their father used to sing, his time in Gandhi’s Sevagram, books he wrote, his autobiography in Esperanto. She talked about Laksmisvar’s early travels, an uncle who lived in London, the Swedish loom which came to Santiniketan through her father, a Swedish woman who came to her some years ago, on the trail of an aunt who had come to teach weaving in Santiniketan in the 1930s. Like Laksmisvar’s own life, Sumitra’s stories too were going in many directions.

I had gone with my friend, publisher Sumita Samanta to meet Sumitra Sinha and the following videos were all recorded by Sumita on her phone.

Sumitra Sinha talks about memories of her childhood in Rarishal, relatives in Shillong, her father’s songs and how there might be some recordings with the family of a deceased student and colleague.

Sumitra Sinha listens to her father’s songs. Her eyes light up. When he sings ‘Hari bolo nouka khulo’, she says, ‘Bhatiyali!’

Pages from Srihatter Prachin Sankirtan, with the song ‘Gour Sonar Manush’.

Sumitra’s stories about her father’s travels in Europe do not all corroborate with Laksmisvar’s autobiography in Esperanto, Jaroj Sur Tero, published in 1966. This leaves us thinking about how the same things are remembered differently by different people and how they are recorded. Whose version is most correct? Why does Sumitra have a version which is different from Laksmisvar’s? Details of the stories she is recalling have probably got jumbled up in her head, the chronology might not be correct, but surely such things happened; surely she had heard such stories from her father. Stories such as her father rescuing a little girl on a ship on a stormy night, the girl’s grandfather sending him a parcel of clothes in London to say thank you and so on. If I could talk with Sumitra’s sister, Tapati, who lives in Sweden, perhaps she would have another version of the same story?

Sumitra Sinha shows us photographs of her parents and from Laksmisvar’s journeys. Sumita takes photos of the photos. The second video was recorded by me on my mobile phone

Sumitra Sinha says her father spoke mostly with a Sylheti accent, while her mother, although she too was from Sylhet, was a Calcutta girl and spoke like one.

Sumitra Sinha tells the story about how a few years ago a Swedish woman came to visit her in Banalakshmi. She said her aunt used to teach weaving in Santiniketan and she had come because Laksmisvar Sinha had been to Sweden. Sumitra had with her some old Swedish weaving patterns from her father’s time, so she gave those to her Swedish guest. What would I do with them? I felt quite relieved after giving them to her, she said.

According to Sumitra Sinha, her Swedish guest (whose name was Margareta F. Berg, and who was from Uppsala; Sumitradi gave me her contact details) later went around Santiniketan, looking for people who had old bedspreads and tablecloths with Swedish designs, and ended up finding twelve looms and many related documents. Ms Inga Jeanson or Ms Aina Cederblom—whose niece was Margareta? I wrote to Ms Berg and she wrote back to me on 17 January 2021. Her aunt was Ms Jeanson, one of the two Sloydists sent to Santiniketan in 1934-35 by Countess Hamilton, on Laksmisvar’s request on behalf of Rabindranath Tagore. Margareta said in her email to me that she would not write any book, because she was 80 now, and did not have enough material for a book.

Swedish weaving. Source: internet.

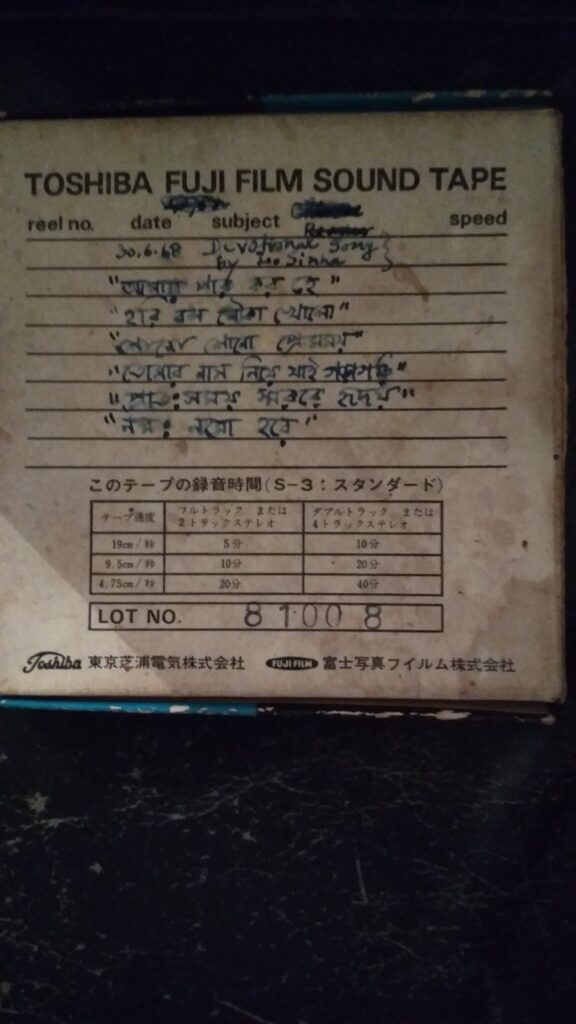

Sumitra Sinha had told me about Laksmisvar Sinha’s student and later his colleague, Aboni Halder, who had recorded her father’s songs quite late in his life. Aboni Halder has passed too, but his wife and daughter, who live in Bolpur, might have the recordings, Sumitradi had said. Sumita Samanta and I went to meet Roma Halder, Aboni Bhusan Halder’s widow in her home on 29 April 2019. She and her daughter Amrita were very warm and welcoming and we chatted for long, and saw the beautiful woodwork of Aboni Halder, heard his stories and another world began to open up for us. Mother and daughter confirmed that there were recordings; Aboni Halder had brought a tape recorder from Denmark. Laksmisvar Sinha was his guru, not only in carpentry but he had also instilled in him an interest in Esperanto. I asked Amrita to look for the tapes because they were so precious.

Roma Halder, also originally from Habiganj in Sylhet who had grown up in Hailakandi in Cachar, talks about her mother and her husband, Aboni Bhusan Halder, and his world of ideas and experimentation. Laksmisvar Sinha was a key person in Halder’s life.

Stairwell crafted by in Aboni Halder in his home in Bolpur, near Santiniketan.

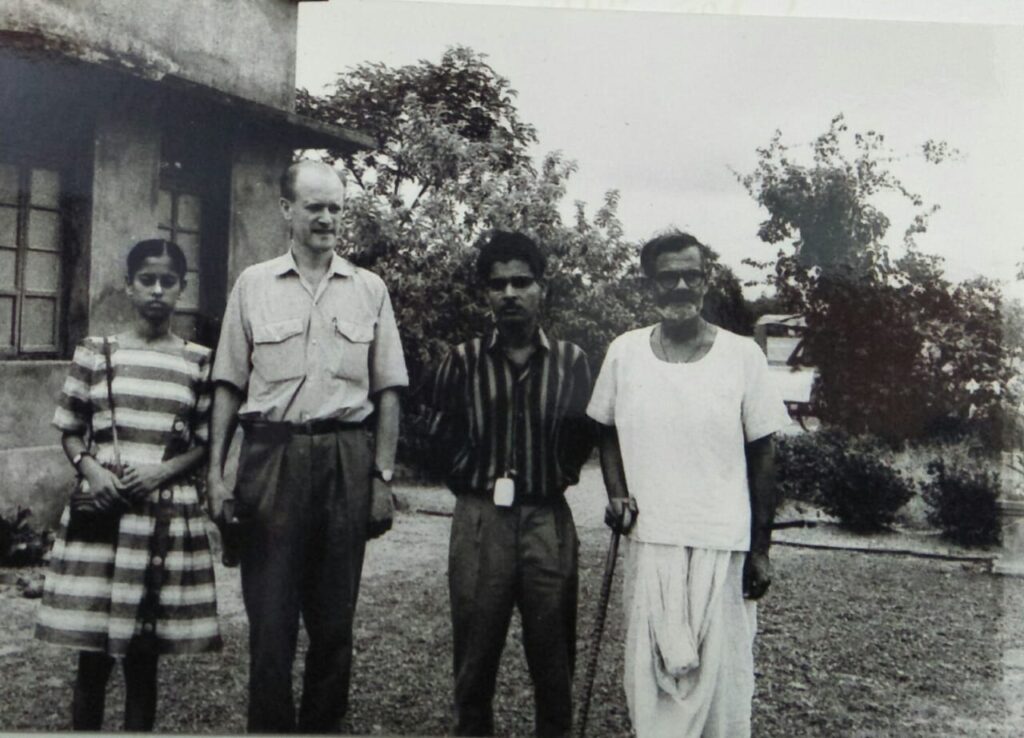

Laksmisvar Sinha stands at the far right and next to him is Aboni Halder

For a whole year I would prod Amrita from time to time about the tapes, although I did not have much hope. In 2020, to my utter surprise, Amrita sent me a message to say the tapes had been found. Then things happened in quick succession. I was helped by friends to bring the tapes from Bolpur and finally digitise Laksmisvar Sinha’s songs recorded by Aboni Halder in 1968. When I heard the song ‘Amay par koro he’, it brought tears to my eyes. For people like me who have spent many years working with field recordings and recording in the field, this was truly a blessed moment. Among other things, Laksmisvar also sang the song ‘Hari bolo nouka kholo’, as he had done in 1933. I do not know whom I must thank for this chain of events and accidents of meetings which led to us these rare recordings of Laksmisvar Sinha. But I am grateful to record collector Rajib Chakraborty for taking these old and delicate reel-to-reel recordings to sound engineer Abhimanyu Deb and to Abhimanyu for the passion he put into the transfer. Therefore, listeners, listen with the attention that all these beautiful people deserve. Listen to the layers of time in these recordings, listen to the ageing of the voice, the deepening of the sound. Laksmisvar Sinha was no ordinary man.

Amay Par Koro He

Hori Bolo Nouka Khulo

Shuno Shuno Premomoy

Joto Shob Kanar Hat Bajar

Tomar Nam Niye Jai Goragori

Bramhasangeet

Nomo Nomo Hare

Nomo Nomo Hare take 2

Esperanto

These recordings from 1968 should not need any explanation, except that there is a subtle difference between Tracks 7 and 8. In 7 we will hear that Laksmisvar Sinha was forgetting one word and so we can assume that he asked to record the song again. The second take of ‘Nomo Nomo Hare’ does not have the spontaneity of the first take, however. There were several other tapes in the lot. Some recordings of Esperanto, the value of which only scholars and specialists can tell us. Interestingly, some of the songs Laksmisvar Sinha sang for Aboni Halder are also in his anthology of kirtan from Sylhet.

Songs from Srihatter Prachin Sankirtan

I shall end this piece here, as I am not equipped to write about Laksmisvar Sinha the Esperantist. Professor Probal Dasgupta, the linguist’s essay ‘Recontextualizing Lakshmiswar Sinha’ gives an idea of the man’s importance as an Esperantist from South Asia on the one hand and his manual labour-based pedagogy on the other. Professor Sajal Dey, also a linguist, has translated Sinha’s autobiography, Jaroj Sur Tero, from the Esperanto into English and Bangla. When the translations are published, readers will know more about Laksmisvar Sinha and better understand the man behind the voice recorded on Arnold Bake’s wax cylinders. For me, my journey began with this voice, and slowly I have come to find his books, learned about his journeys, understood somewhat the impulses which drew him to the world of carpentry from when he was a boy, to cotton cultivation, to Esperanto, to translations of Swedish texts into Bangla, while he held his songs of devotion from his village home close to his heart.

I end with one question which is more about Arnold Bake and less about Laksmisvar Sinha. By the time Bake met Sinha, the latter had returned from Sweden trained in Sloyd. Here was a man who had journeyed from the far end of Bengal to its centre, a man interested in Rabindranath and Gandhi, who had been taught by Leonard Elmhirst. It was Tagore who had sent him to Sweden. Here was a man who came from a curious family of artistes and intellectuals–his cousin the Leftist intellectual and scholar Sasadhar Sinha had studied at the London School of Economics and ran an eclectic bookshop in London . This man whom Bake was recording had travelled across many places in Europe. Yet Bake did not seem to take any particular notice of him. Of course, he recorded him and those recordings are invaluable and without those I would not have done this work, but that is not the point I am trying to make here. I wonder what it was in a song or a singer that used to catch Arnold Bake’s imagination and draw his attention? Likewise, what does this absence of information tell us about Bake? Or does it tell us something about the place of Laksmisvar in the world of Santiniketan?

Finally, in the mid 1940s, Laksmisvar Sinha had planned to start a whole agriculture and other handicraft-based holistic project in near Rarishal, for the ‘villagers’ as he wrote in his autobiography, in the place where his father, Baneswar Sinha, had his farm when they were small. That was also the place where his father went alone, to meditate. That project had taken off alright and Laksmisvar had hopes of going far with it, working with the people in his homeland. Then came Partition and the riots and his dreams were shattered, the place and the project destroyed. Laksmisvar had to take a job in Sriniketan, Visva Bharati where he was mainly based for the rest of his life. I asked Bappi, my friend from the Sinha family in Rarishal, about Sinhagarh. He said there was no Sinhagarh, but Sinha Gram, a village not far from Rarishal. And he sent me these photos from Sinha Gram on 17 January 2022.

Postscript

I had closed this sub-chapter with the above photos. However, on 8 August 2022, I had a message from Bappi in Rarishal, the distant great grant nephew of Laksmisvar, after he read this piece. He sent me another photo of the temple in Sinha Gram. (Above, in the bottom left photo, Sinha and Gram are written as two words. The photo below has the name as one word). Now he has got the temple committee to write the name of the temple, place and year it was established on the parapet of the roof. In a sense this is like filling up gaps in archival notes, labelling unnamed objects in an archive and here the place itself is the archive. Bappi wrote to me that our trip to their home in 2018, with Laksmisvar Sinha’s songs and our continued communication over the years have given him another consciousness about the importance of their history and the need to tell and retell the stories of this place and mark it with signs.

Bappi wrote, আমার চাকরি সিংহগ্রামেই তবে মন্দিরে খুব একটা যাওয়া হয় না। সেদিন গিয়ে যখন দেখলাম নামটা নেই, খুব খারাপ লাগল। সেদিনই কমিটির লোকদের বলে আসছিলাম যে আমি মন্দিরের নামটা লিখিয়ে দিব। আসলে সেটাতো আপনার জন্যই হল দিদি না হলে হয়তো যাওয়াও হত না সেখানে। ‘Sri Sri Shib Mandir, Sinhagram. Lakhai, Habiganj. Established 1313 Bangabda, 1907 CE’–this is what is written on the board. Photo: Sanjit Sinha Chowdhury.

- Imam Bux Boyati of Mymensingh at Gurusaday Dutt’s Suri Mela

- Motru Sen and Jaya Tagore: From Image to Sound

- Mapara’s Cradle Song and Shruthi Vishwanath’s Response

- The Bauls of Kenduli in 1932

- Pinakin Trivedi and the Autograph Book

- Roof-Making Songs of Baori Women

- Listening to Savitiri Govind with Sumana Chandrasekhar

- From Ranjan Shaha to Kobiyal Akhtar Shah in Kasba, Birbhum

- Kusum, the Nachni and her Jhumur

- From Gurudayal Malik to Mohan Singh Khangura and Madangopal Singh