Motru Sen and Jaya Tagore: From Image to Sound

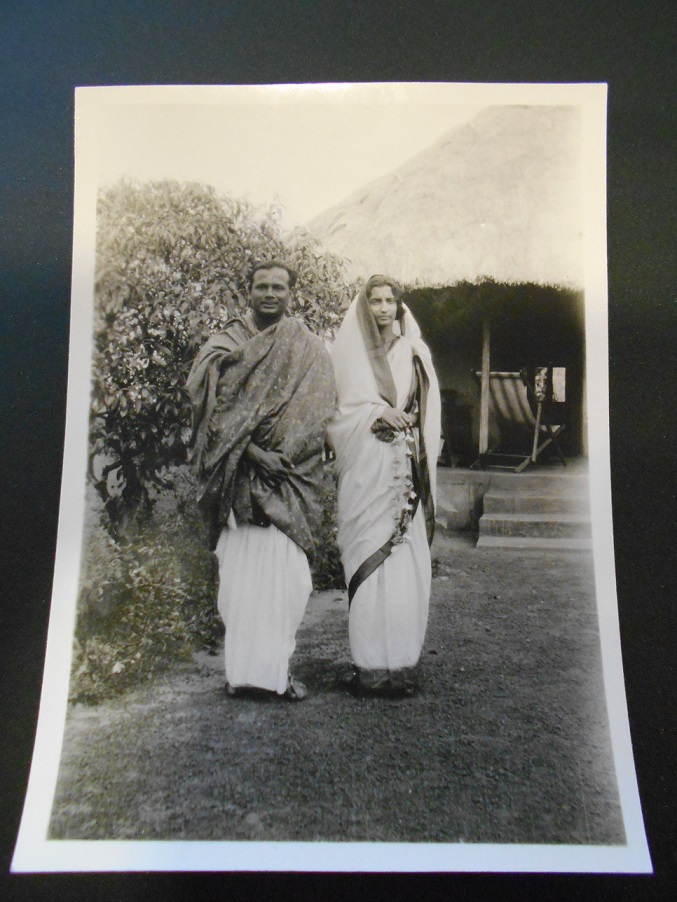

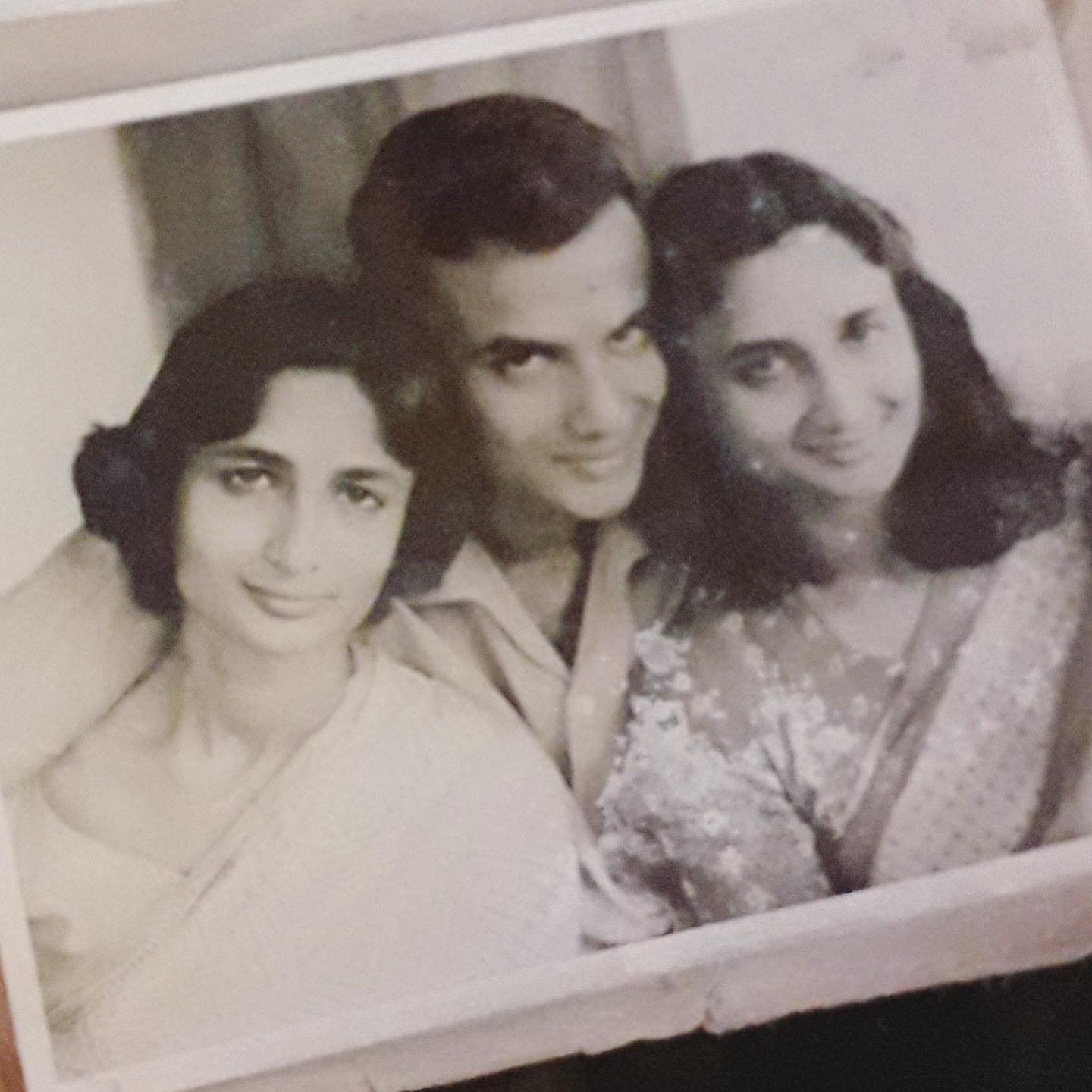

It began with a photograph. Jaya Tagore, grand-daughter of Satyendranath Tagore, elder brother of Rabindranath, with Kulprasad alias Motru Sen, her husband. As much as I understand, the photograph was taken in front of the thatch-roof house, the aatchala, where Arnold and Corrie Bake used to stay during their first four years in Santiniketan, between 1925-29. Jaya Sen was, incidentally, my close college friend Ayesha (journalist Ishani Duttagupta)’s grandmother, her Didimum, whose stories she used to tell us all those years ago. When I saw the photo in the archives, and read the description on its back, something seemed very familiar, but I could not make an instant connection. From there to Tagore’s songs sung by Motru Sen, recorded in 1962–it was another rich world of sound, image and story which I was led into.

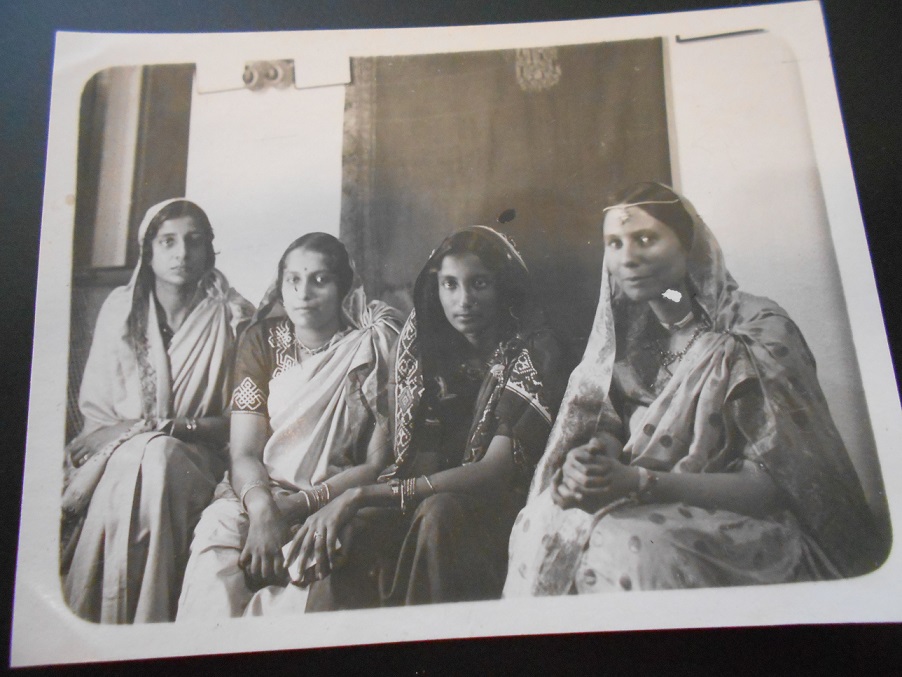

Arnold and Corrie Bake were friends of Jaya, her sister Manju, and Jaya’s husband Motru Sen as we know from Corrie’s diary entries and photos in the Arnold Bake archives of the Special Collection of Leiden University Library.

It was my old teacher Shibaditya Sen, Kshitimohan Sen grandson, who helped me identify the photograph when we (Sukanta Majumdar, Dutch translator Jan-Sijmen Zwarts and I) visited his house with the photographs of Arnold Bake on 18 January 2016, in preparation for The Travelling Archive’s Time upon Time exhibition. I called Ayesha and asked her if I could go over to meet her mother. So, on 22 February 2016, I met Haimanty Dattagupta, daughter of Jaya and Motru Sen, in her home in Kolkata. Ayesha was there too and they brought out their photos and I opened my files and there was so much unpacking of anecdotes which happened that day. This sub-chapter demonstrates how unpacking the anecdote works as a research methodology, the simultaneity of its lightness and depth, because what seems like mere adda is also when we were peeling off and piling up layers and layers of history. We were munching biscuits, having tea, looking through photographs and talking. Where is this one from? O from England, Ayesha said. ‘Didimum and her sister, Manju, were sent off to school in England. Where did they go, Ma?’ Ayesha asked. ‘To Bristol. To Duncan School. Rabindranath arranged for his two grand-nieces to be educated there. It was a crazy plan. They did not know a word of English and here they were in the English countryside, left to fend for themselves. All the girls gone home during the holidays, the two girls alone in the huge big school.’

Jaya Tagore and Motru Sen were a beautiful and romantic couple in Santiniketan. They married in 1927, on a Spring day, ‘Phaguner Choutha’, the fourth day of the Bengali month of Phalgun. Rabindranath had gifted them a poem, While wishing for them a long, happy conjugal life, he also pulled his grandniece Jaya’s leg and told her she better learn to fry nice round luchis for her husband and not serve him leathery round things which will make the cobbler jealous!

পাক প্রণালীর মতে কোরো তুমি রন্ধন,

জেনো ইহা প্রণয়ের সব সেরা বন্ধন।

চামড়ার মতো যেন না দেখায় লুচিটা,

স্বরচিত বলে দাবী নাহি করে মুচিটা,

পাতে বসে পতি যেন নাহি করে ক্রন্দন।।

Born in 1939, Haimanty was one of the triplets Jaya had, after two sons. In this clip from her nearly hour-long recording, we can hear the joy in her voice at seeing her parents’ photograph, and her aunt in another one.

Haimanty Dattagupta talks about her father

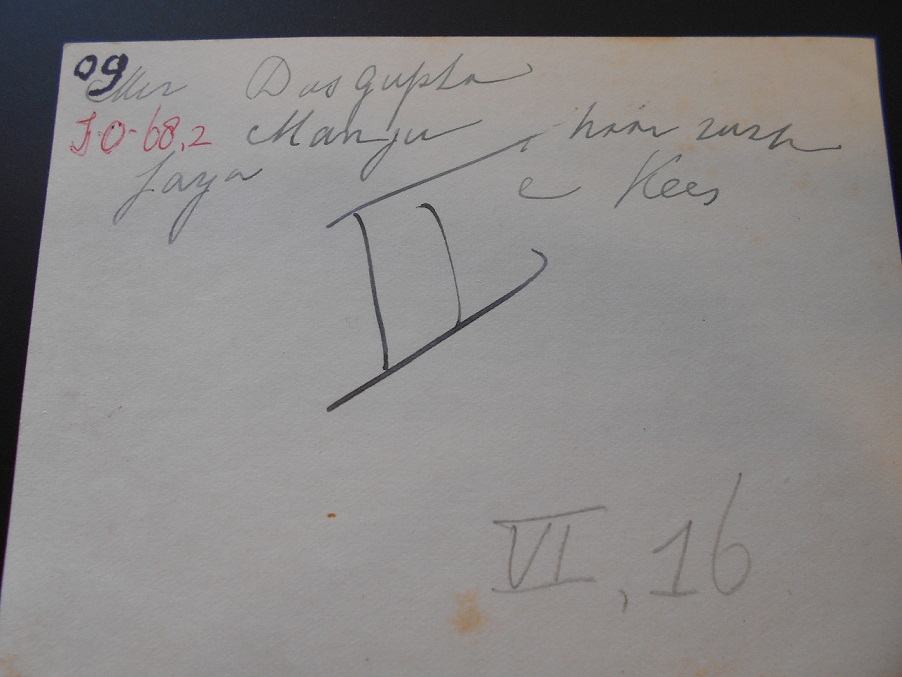

Cornelia Bake with Jaya and Manju Tagore and a Mrs Dasgupta. ‘Who in this group is Mashi?’ Haimanty Dattagupta and her daughter were slightly confused at first, then settled for the woman next to her mother. This is a photo of a photograph from the Arnold Bake archives of the Special Collection of Leiden University library.

The triplets, Jayanti, Haimanty and Sunandan. Courtesy: Family of Haimanty Dattagupta

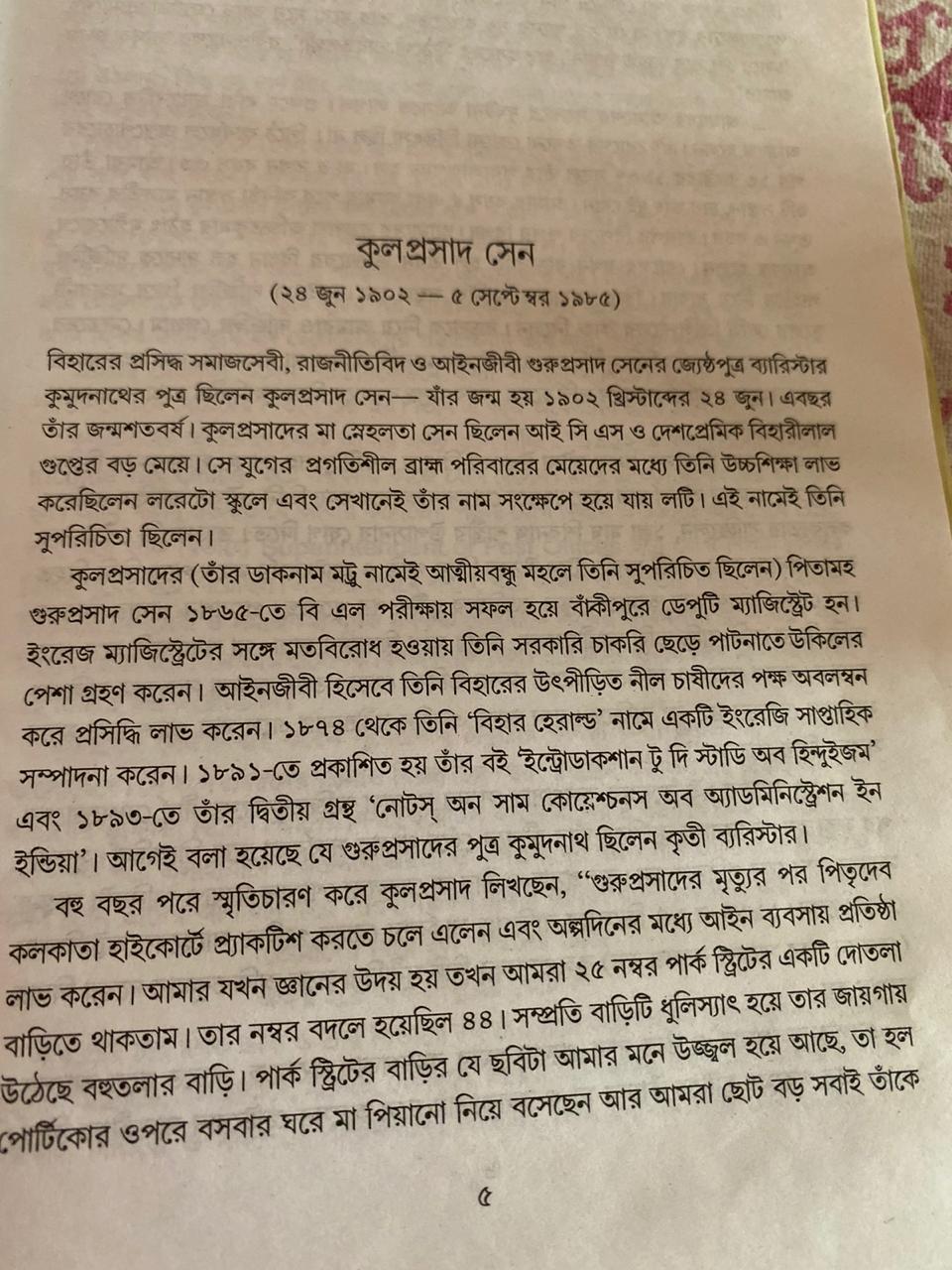

Haimanty began to recall stories, as Ayesha and I prodded her with questions. What was her father’s connection with Santiniketan? Where was their ancestral home? Soft-spoken Haimanty Dattagupta described her father, Kulaprasad Sen, as a ‘truly fantastic’ person. He used to work in the postal services and retired as Post Master General, so they lived in many places and the children kept moving school. Then he bought 12 bighas of land in Santiniketan, to grow things, build a house and settle down, while also working as the officer in charge who set up the museum in the Tagore house in Jorasanko, Kolkata, during Tagore’s centenary year. He was given the task by the then Chief Minister of West Bengal, Bidhan Roy. Kulaprasad was also responsible for propagating the works of Tagore by organising the publication of the low-price edition of his complete works. Their Santiniketan connection went back a long way, to Kulaprasad’s grandfather’s time, because the Tagores and the Sens were family friends—early ICSs, first batch, second batch and so on. When Kulaprasad’s father died, they were very young—he was five, his younger sister was three. Their mother, Snehalata Sen, was one remarkable woman who came from a highly Anglicised family, went to Loreto Convent, but later when she had to fend for herself and bring up her children by herself, she taught in various schools till Rabindranath asked her to join the asram as the supervisor of the first girls’ hostel.

Former Indian PM Lal Bahadur Shastri looks on as Snehalata Sen lights a lamp to inaugurate a girls’ hostel in Santiniketan. The year, possibly, was 1964. Photo very generously shared by Ishani Duttagupta.

Haimanty on her paternal aunt, Malati, as an untameable young girl.

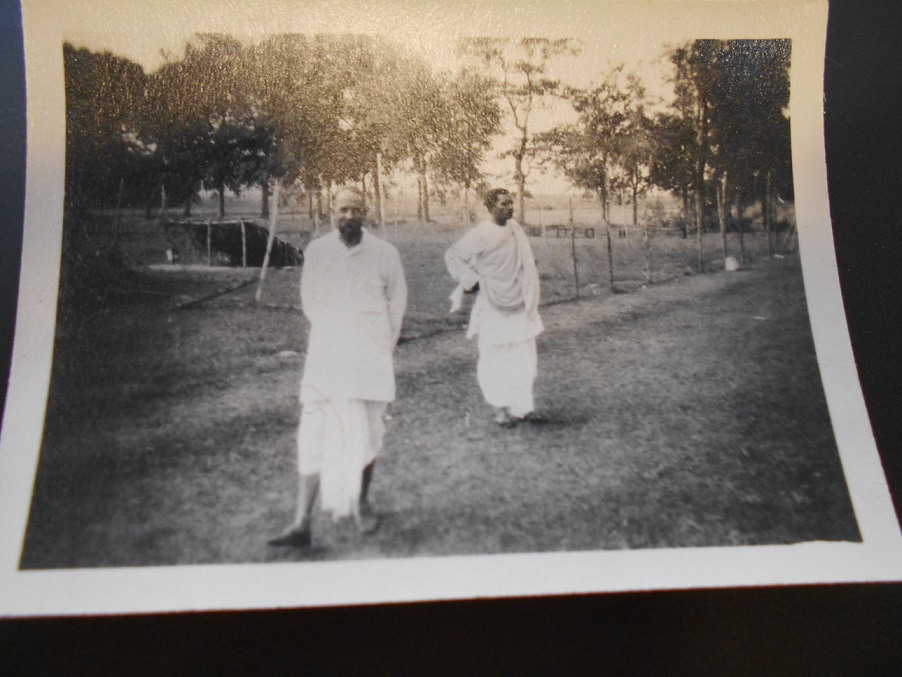

As I was showing her photos from my folder, we came upon one of C. F. Andrews and P. Lal, both of whom were very active in the Sriniketan rural reconstruction project (the latter I get mixed up with the Swiss-French linguist, Fernand Benoit in the above audio clip).

Andrews and Lal. Photo from Arnold Bake Collection of Special Collections, Leiden University Library

We got talking about Andrews, the Anglican priest who was close to Gandhi and Tagore. Haimanty Dattagupta said, ‘There is a funny story about my aunt, Malati, then just a school girl. Once she had this idea and went to Andrews’ house with a friend. He was out at the time. So she said to whoever opened to door, “O, but he had invited us!” Then this person made food for them, which the girls happily ate and left.’ Ayesha and I laughed so much. This wild girl later went on to become a famous social worker in Orissa. Haimanty looked through the photos to see if there was one of her pishi too, but we could not find any.

This picture of Malati Sen was once on the cover of Illustrated Weekly of India. Ayesha sent it to me with the following note from Malati’s daughter, Krishna Mohanty: Malati Sen was a student of Visva Bharati, Santiniketan from 1920-26, in the first batch of girl students. Her mother Snehalata Sen was superintendent of girl’s hostel and also a teacher. Malati/Minu, besides her regular studies in Visva Bharati, learned music, dance, drama and so on from Gurudev Rabindranath himself and Dinendranath, Pandit Bhimrao Shastri and the veena from Guru Sangameshwar Shastri. Among all the pupils of Sangameshwar Shastri, Malati continued her practice of veena even after she married Nabakrushna Choudhury, a famous social worker of Odisha, who later became Chief Minister of the state. They were Gandhians, lived away from the city, did farming and worked among the rural poor. It was Malati’s earnest desire to see a society without any creed, caste or class. With her very busy schedule, whenever she got little leisure she used play the flute. Early in the mornings she would play tunes of Rabindrasangit or Karnataka music on her veena. Malati sang in her melodious voice to gather crowds at freedom movement meetings or marches between 1930-42. She lost her this veena in the 1942 movement, when she was imprisoned for three and a half years. About this she would say, ‘We have lost Gurudev, we have lost Bapu, this is a mere instrument.’

Music clearly was in their blood, because Malati’s elder brother, Motru Sen was a gifted singer and he could also play many instruments. In 2020, Ayesha sent me two songs of her grandfather on whatsapp and I was amazed to listen to them. She said there was a whole set of songs which had been recorded in 1964, in Jorasanko, after the house had been converted into a Tagore museum. Kulaprasad Sen had been officer in charge of this project, as we know. There might have been a studio or an office in the house where these recordings were made—the family is unsure of the provenance of these recordings. However, Kulaprasad’s younger son, one of the triplets, had the original tapes and made copies for the rest of the family. One other granddaughter of Jaya and Motru Sen, historian Samita Sen, later digitised the magnetic tapes and I am very grateful to the family of Jaya and Motru Sen for allowing me to keep these songs in my archive of Arnold Bake. The recordings below are many times removed from the original, yet they are a record of a time and of a style of singing and training early singers of Tagore’s songs received. Arnold Bake and Motru Sen were about the same age, the former born in 1899 and latter in 1902. They were taught by the same teachers–Rabindranath and Dinendranath. Moreover, they were also friends.

The tape starts with the following announcement, which I have learned was in Kulaprasad’s own voice. But he speaks in a way as though he was talking about someone else. We can hear him turning on the recorder. ‘These recordings in the voice of Kulaprasad Sen are being made as part of a project to archive and preserve the melody and style of Rabindrasangit of India. He goes by the name of Motru in known circles. His maternal grandfather Biharilal Gupta’s family were close friends of the family of Rabindranath Tagore. Kulaprasad’s mother, Snehalata Devi, now over 90 years old, was a classmate and close friend of Indira Devi. Snehalata Devi was proficient in Western music and she learned Rabindrasangit in the early days in the Jorasanko house itself. Kulaprasad’s first lessons in Rabindrasangit were from his mother. Later, as a boy, he had lessons from Sangitacharya Surendranath Bandopadhyay. He had the opportunity to learn directly from Rabindranath and Dinendranath in 1328 BS (1921 CE), during the first Barsha Mangal or Monsoon Festival in Santiniketan. Kulaprasad participated in that programme. He was 19 at the time. After this He went to Santiniketan and lived there for about three years. He used to take regular lessons from Dinendranath at the time, and also from Rabindranath and took part in the asram’s various ceremonies and festivals. Once he performed solo at the [Brahmo] Magh Utsav on 11 Magh [in February] and was much praised for his songs. Here he is has sung those songs which he learned directly from Rabindranath or Dinendranath. Kulaprasad is now 62 years old and his voice is not good enough. We cannot however expect him to have the voice he once had. First he will sing two songs which were written for the first Barsha Mangal, to the accompaniment of the pakhawaj.’

Here is the list of songs on this recording, with the starting time in brackets. After the first two songs, Kulaprasad Sen strums the guitar to the beat of the song, and sings. He does not play any chords, it is just a regular rhythmic strumming, as if he was playing the drone. That it is him strumming is something his daughter Haimanty told me, because he used to sing this way at home too.

Jhoro jhoro borishe (00:02:35)

Aaj bari jhore jhoro jhoro (00:06:33)

Ogo amar kheya torir majhe 00:09:56)

Timiro abagunthane (00:13:23)

Ei srabaner buker bhitor aagun achhe (00:16:08)

Badalo meghe madalo baje (00:18:52)

Megher kole kole jaay re chole (00:22:10)

After this set Kulaprasad announces that while the earlier songs were specially written for the first Barsha Mangal, the next ones are monsoon songs which already existed and which were also sung on that occasion.

E bhora badoro, maho bhadoro (poem of Vidyati, composed by Rabindranath) (00:24:50)

Abar eshechhe asharh (00:28: 31)

Haare re re re re amay chhere de re de re (00:30:57)

Kulaprasad then makes an announcement about the next song and says he is singing it in two rhythmic patterns and in two tempos as there are two versions of the song.

Amar nishitho raater badalo dhara (00:33:09)

When he sings in the slower 4/4 beat, he says nishitho, badolo. When the song becomes a faster paced dadra in 3/4 rhythm, nishitho becomes nishith, badalo becomes badal.

Bishwabina robe bishwajono mohichhe (00:38:37)

Srabaner dharar moto poruk jhore (00:40:56)

Dukkher boroshay chokkhero jol jei namlo (00:00:10)

Gaaner shurer aashonkhani (00:01:54)

After the first two songs, Kulaprasad gives a brief description of what is to follow. In the beginning of 1921, a bunch of students joined Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement and went to Surul Kuthi to stay and work. Departed teacher of Santiniketan. Nepal Chandra Roy, led the team, which Kulaprasad had also joined. There used to be meetings in village Surul, in Bolpur and other neighbouring places. Dinendranath would often join the meetings with a team of singers. Kulaprasad will now sing some of the patriotic/national songs they used to sing in those days. The tunes might vary from how they are sung now, but Kulaprasad is singing as he had been taught by Dinendranath.

Nishidin bhorsha rakhish (00:07:43)

Ami bhoy korbo na bhoy korbo na (00:10:19)

Je tore pagol bole taare tui bolish ne kichhu (00:12:08)

Jodi tor bhabna thake phire ja na (00:13:52)

Ma ki tui porer daare pathabi tui gharer chhele (00:16:40)

Amra pathe pathe jabo shaare shaare (00:18:54)

Before the next song the announcement goes that this is the song Kulaprasad had sung at Jorasanko on the day of the Magh Utsav; he had learned it from Indira Devi.

He moro debota (00:21:34 )

Then he talks about the department of agriculture in Surul which the British agronomist Leonard Elmhirst had started in 1921. Later it came to be called Sriniketan. In the beginning there were some 10-12 boys, Kulaprasad was one. The next song is related to this project.

Phire chol maatir taane (00:28:36)

Then Kulaprasad explains how the next song came to be composed, how a dance with small cymbals that Rabindranath had seen was the inspiration

Dui haate kaaler mandira (00:31:02)

It sounds like there were more songs, but the tape abruptly stops.

The files Srila Sen, my friend Ayesha’s cousin, sent to me came with this photograph of Jaya and Motru Sen. It must have been taken around the same time when Arnold Bake took his photo.

And here are some pages from a commemorative volume on Kulaprasad Sen, published by his family. This piece was written by the Marxist historian Gautam Chattopadhyay (1924-2006), son of Jaya’s sister Manju.

- Laksmisvar Sinha, a Doorway to Many Worlds

- Imam Bux Boyati of Mymensingh at Gurusaday Dutt’s Suri Mela

- Mapara’s Cradle Song and Shruthi Vishwanath’s Response

- The Bauls of Kenduli in 1932

- Pinakin Trivedi and the Autograph Book

- Roof-Making Songs of Baori Women

- Listening to Savitiri Govind with Sumana Chandrasekhar

- From Ranjan Shaha to Kobiyal Akhtar Shah in Kasba, Birbhum

- Kusum, the Nachni and her Jhumur

- From Gurudayal Malik to Mohan Singh Khangura and Madangopal Singh