In Search of Sawabali

Sawabali of Bake Indien II cylinder 351, like the other seamen on the Streefkerk, was recorded and his disembodied voice was taken to an archive. There it lay for about 85 years. Then I, through a fortuitous string of events, became a vessel for the song to return home. Yet, when I reached his home, I realised that Sawabali’s song had never left at all. A man long dead, he felt like a living presence in his home, a light that gently burned. If anything, the returned voice made that presence even more real.

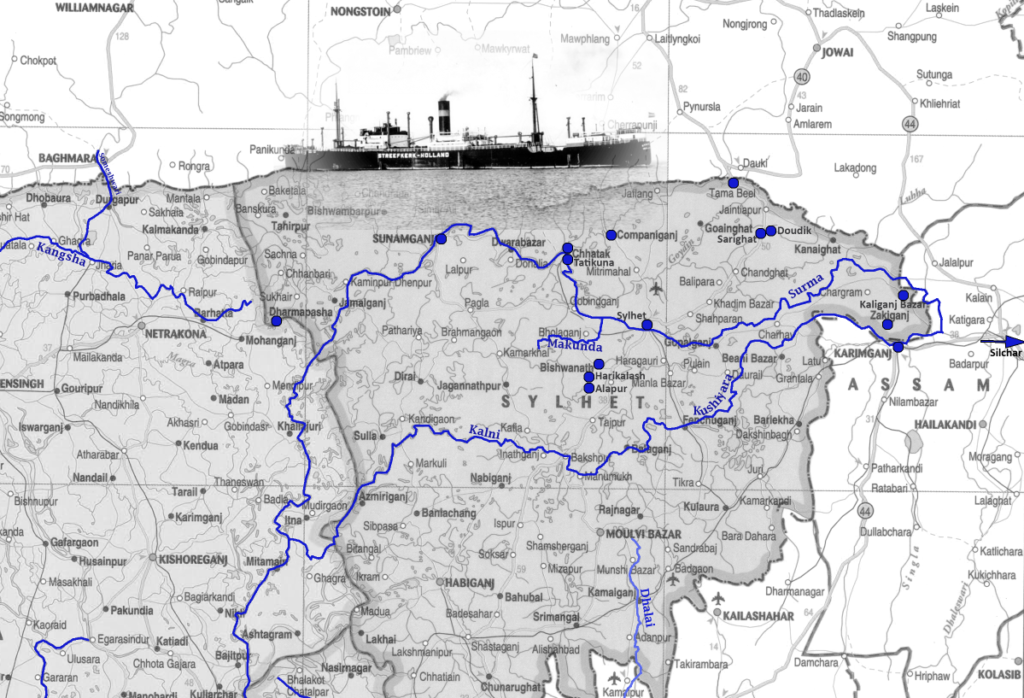

Map designed by Purba Rudra, showing the places where we went looking for the Sylheti seamen Sawabali and Fayzullah whom Arnold Bake had recorded in 1934

Songs about voyaging towards the unreachable shore and searching for the majhi to take us across abound in the repertoire of spiritual songs from this eastern part of Bengal. Sawabali was a man who sang such ‘pir-murshider gan’; he had a job as an ‘oilman’ on the ‘Streefkerk’, a cargo ship sailing from India to Europe; he was recorded by Arnold Bake on board this ship on 15 April 1934, on Bake India II, cylinder 351.

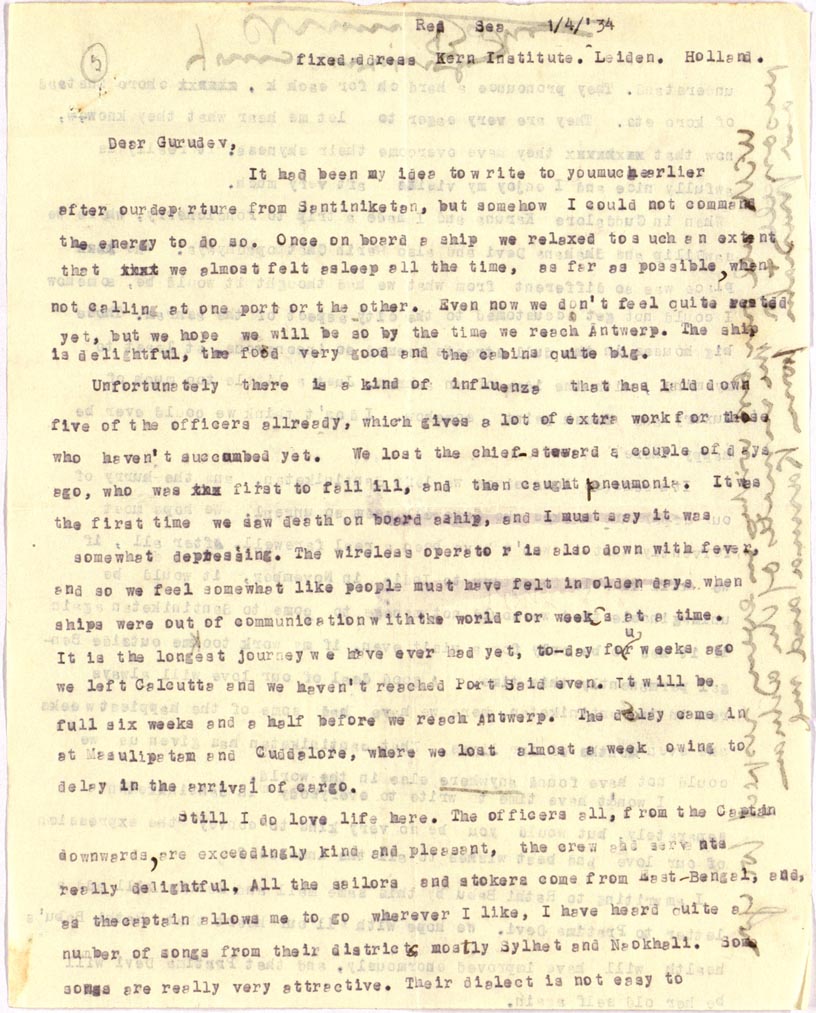

Letter from Arnold Bake to Rabindranath Tagore. Courtesy: Rabindra Bhavan archives, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan

‘… I do love life here,’ Bake wrote to Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore, from his ship on 1 April 1934, while sailing on the Red Sea. ‘The officers all, from the Captain downwards, are exceedingly kind and pleasant, the crew and servants really delightful. All the sailors and stokers come from East Bengal, and the captain allows me to go wherever I like. I have heard quite a number of songs from their district, mostly Sylhet and Noakhali. Some songs are really very attractive. Their dialect is not easy to understand. They pronounce a hard ch for each k, choro instead of koro etc. They are very eager to let me hear what they know, now that they have overcome their shyness. It is really awfully nice and I enjoy my visits aft very much’ It must have been this dialect, ‘not easy to understand’, which resulted in some errors in the notes that we have for the recordings, and which led me for several years through a maze of broken roads and changed place-names till I found the home of Sawabali in 2018.

According to the archival notes, ‘Sawabali (oilman)’, was from ‘gram Harikhailash. po. Bisvanath, Sylhet’. When I had sent these details to friends Ambarish Dutta and Suman Kumar Dash, journalist, music researcher and writer, they said as far as they knew, there wasn’t a Harikhailash in Bisvanath but a village by the name of Harikalash in Bishwanath thana area.

I went with friends Ambarish Datta and Tushar Kar to look for Sawabali in Harikalash on 16 January 2018. Photo: Moushumi

Ambarishda had a contact in the ‘Hindu para (neighbourhood/mohalla)’ of Harikalash, so that became our first stop. The people in this house weren’t very friendly or helpful, but a young man started walking with us as we were leaving and he said he would take us to an old man of about 80 or 90 years, in their same neighbourhood, who might know something. Our next stop was at 83-year-old Pachon Malakar’s house. And it was from here that the story of Sawabali began to slowly reveal itself. I am consciously using the word reveal here, because that afternoon, after a point, it seemed that we were no longer in control of the story, but something was happening before our eyes and all we could do was to submit ourselves to this revelation.

Pachon Malakar, Harikalash, 2018.

Pachon Malakar (Fyason Malakhar is how they pronounce the name), a little short of hearing, had to be asked the same question more than once. But he remembered a lot. He remembered the brothers Sawabali, Meher Ali and Akon Ali; the latter had gone to London and then came back and died here; Sawabali too had gone to London. Sawabali was a piraki, this was a prominent family, a piraki household. Sawabali’s father was Romdi Pir, an interpreter of life and a spiritual healer. With the pirs, the interpreting and healing is often done through the means of music. Ganja khaita, Sawabali smoked ganja. Ambarishda and Pachon Malakar talked, I mostly listened. I had to be extra attentive to their Sylheti accent and words, so that I did not miss anything. He said the old house of Sawabali was east of Tamizullah’s house, তমিজুল্লার বাড়ির পূবের বাড়ি; he gave directions to the young man who had brought us to him.

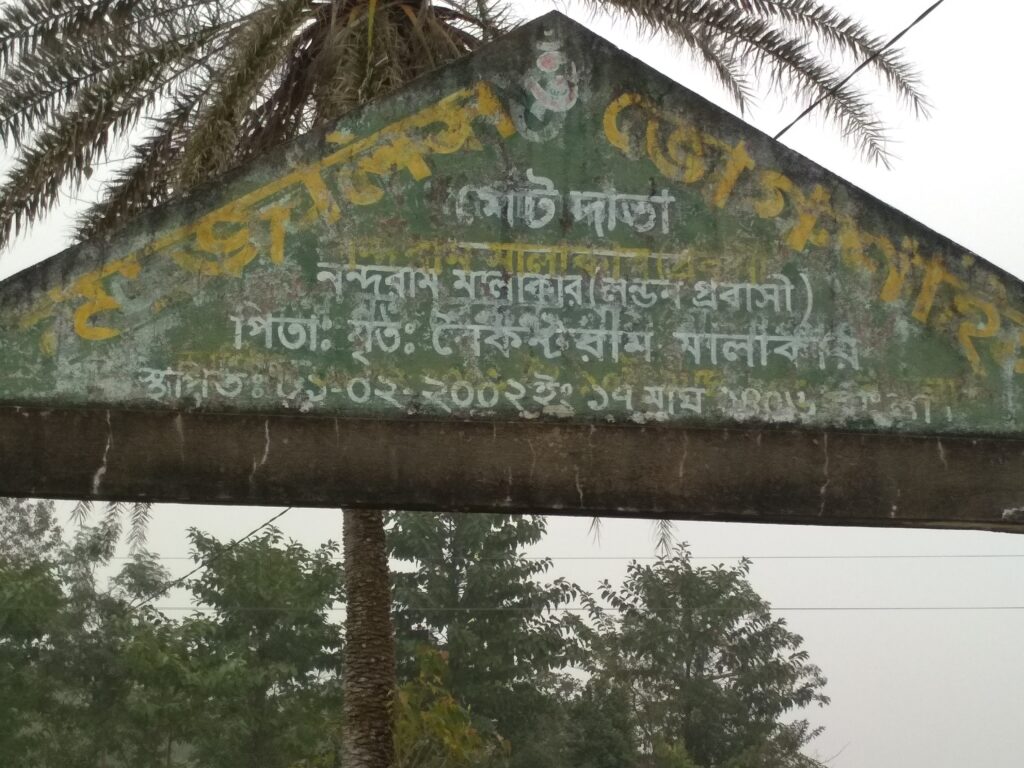

From Pachon Malakar we walked through this typical Londoni village of massive (alishan, as Ambarishda was saying) empty houses, the kind of place that Katy Gardner writes about, to an old house which used to be Sawabali’s.

The massive houses have massive gates and plaques announcing that the owner is a Londoni. Photo: Moushumi

Recording from the courtyard of the house which used to be Sawabali’s. 16 January 2018. Recorded by Moushumi on a Zoom H4N recorder.

Here we moved one step further, learning more about Sawabali and his brothers. In the courtyard there were several people who had gathered, some who lived in the house, some younger and older people of the neighbourhood. The murubbi of the village—wise women and men who had seen and heard about other times. Sitara Bibi, Abdul Kader, Hajera Bibi. Ambarishda explained the context, it was better he did the talking, because he was sonically and idiomatically closer to those we were meeting. Sawabalir fochashi bosorer recording tain tukaiya faisoin, she has searched and found Sawabali’s record from 85 years ago, Ambarishda was explaining the reason behind our visit. The audience was amazed. They knew about Sawabali, some had even seen him. They weren’t his relatives and this wasn’t their family history. But Sawabali’s story was part of the memory of the community. ‘They had fallen into hard times,’ people remembered. Sawabali sold off the house and went away somewhere, with his family. People talked about his two marriages (dui torof), death of his daughter (his furi), Mala, from his first marriage. His return from years on the sea to Harikalash, his second marriage to Tezab, there was a son who died, then she had two more sons and a daughter, Minara, who also died. Gaan bazna je korten dekhsen? Did you see him make music with friends here? Oy dekhsi gaaner ashor, ganjar ashor. Yes, we have seen gatherings of smokers and singers. Did he play any instrument? Dofki? Did he play the hand drum dubki? Did he play the dotara? There used to be a lot of people who gathered, Aaro manushjon aisha boita, okhon keu nai duniyat, they have all left this world

In the courtyard of Sawabali’s old house in Harikalash, Bishwanath, Sylhet.

The older men and women who had gathered in Sawabali’s old house talked about how he sold off his property and moved to Alapur, not far from Harikalash. Then he left Alapur too and went somewhere in the mountains and died there, they said. But they were not in touch with his family anymore. There might be some family in Alapur, his sons should be there, don’t know their names, but if you go to Kaliganja Bazar and ask Munir Daktar, he should be able to show you the way, they said. That is the route we took to go to Kaliganja first and then to Alapur. The doctor said, walk down that road and ask anyone where Anfur Ali’s house is.

From Harikalash to Kaliganja Bazar, did not take more than fifteen minutes to reach by a three-wheeler auto rickshaw. Photo: Moushumi

Before we go to Alapur, let us dwell a little longer on Harikalash. In Sawabali’s house, I kept looking around at the house and the courtyard, at people’s faces, thinking of traces. It felt unreal that I was actually in a place where Sawabali was no longer just a voice, but a son of a pir, a husband and a father, with children who had died—so Sawabali now becomes a man with a burden of grief. Here this voice used to fill the air of the courtyard where we were sitting. I could smell the incense and the ganja of the ashor and hear the music. As I looked at the unusually tall women with light brown eyes I was thinking of other journeys into this land which people had undertaken in a distant past–journeys of pirs and fakirs from other geographies with their songs and stories, the coming of Islam to Bengal… thoughts whirled inside my head. There was a middle-aged man who was dressed as a hujoor (Islamic clergyman) in a long kurta, fez (hat) and checked scarf, and he was saying the most interesting and informed things. His name was Maulana Abdul Kadir Kobiraji. A medicine-man by profession, a song-collector by passion. He said it would be good if we stopped by his place before going to meet Munir Daktar.

Maulana Adbul Kadir Kobiraji, a collector of songs. Photo: Moushumi

So we went with Abdul Kadir Kobiraji to his amazing room covered from all to wall with cassettes and CDs and covers of tapes and posters of pallagan concerts, first releases, photos of old dead artists when they were young, shelves lined with radios and cassette players covered with embroidered silk—it was a kind of a magic room which we had entered. There were also photos of Saddam Hussain and Muhammad Ataul Goni Osmani in the midst of the singers, to celebrate a kind of Islamic glory. The maulana gave us his calling card and someday I will have to go back to Harikalash to dig into the wealth of music Abdul Kadir Kobiraji holds in his archive.

Conversations with Maulana Abdul Kadir Kobiraji about his music collection, about 1971 and other things. Recorded by Moushumi on a Zoom H4N. 16 January 2018.

We took a three-wheeler to Kaliganja Bazar and there we met Dr Munir who knew about Sawabali and his sons. He found someone to take us to Alapur.

A beautiful man with a greying beard and very kind eyes met us as we entered his courtyard; the tall betel nut trees (gua gaachh/gaas) stood around, watching. This house was nothing like the Londoni houses of Harikalash, but just a row of rooms with a tin roof and a veranda, all doors open, the rooms quite dark inside, a yellow light glowing like a candle. Anfur Ali? Ambarishda had asked. Yes. Was your father’s name Sawabali? Yes. Sawabullah, actually. The man spoke so softly that you had to strain your ears to listen. He could well have been a poet. Or a pir. So, this was Anfur Ali, the second son of Sawabali, from his second wife, whom he had married late in life. That explained Anfur Ali’s age of 53 years and his younger brother’s, who was just a year-old baby when their father passed away around 1983. As I explained the purpose of my visit and Anfur Ali was getting us chairs to sit, ‘Make some tea,’ he said to the women. ‘Please don’t bother, we have just had tea at Kaliganja Bazar.’ ‘Paan (betel leaf ) then?’ he asked.

Anfur Ali, his younger brother Asar Ali (who was first named Asman), a friend Batir Ali, the women of the house, children, us who had gone from the outside, the young man who showed us the way—we all sat still in their courtyard in the fading winter light, listening to the voice of Sawabali as it flowed under the surface noise of the cylinder. Then, as the song is playing,I hear in my recording of that day, Anfur Ali’s voice above his father’s. ‘Make some tea, make it strong. Said to whom, I do not know.

Anfur Ali is so overwhelmed to hear his father’s voice that he finds it hard to talk. Recorded by Moushumi on her Zoom H4N

The song was over. Everyone was silent. ‘Dhoinyobad, thank you,’ Anfur Ali whispered. The song had opened old wounds, while also taking him to memories of a beautiful time of loving. ‘My father loved me very much, he used to call me Afu.’ He spoke a little, then stopped. Then someone else spoke, maybe his much younger brother, who was sleeping inside the house when we went. He drives long-distance trucks through the night. Anfur Ali works as an electrician, he works when he is hired; they struggle to make ends meet. There was grief in his eyes, but no grievance about anything. It was probably a sense of grief that ran in the blood of this piraki family, a line of seers, poets and healers. Music flowed through them. ‘I don’t usually sing,’ Anfur Ali said. Besides, it is expensive to hold ashors at home, where musicians gather and smoke and have tea and sing, as it used to happen in his father’s time. ‘I go to different shrines and some nights when the song rises in me, I sing all through the night, sometimes all alone.’

Several times in the course of that evening, while sitting in their courtyard or while walking us to the road, Anfur Ali said, ‘Abbay koita, Abba used to say…’, and then maybe just recited a few lines of a song. ‘Will you sing for us please?’ I asked. He said, ‘It is hard you know, when the air is so heavy with remembrance. Who would have thought a voice from so long ago, Abba’s voice… this really is jotheshto paona for us, more than what we could have ever imagined, we shall never forget this day.’

I said, it was actually jotheshto paona on both sides, far greater than what a researcher or field recordist can ever ask for. This is a blessed moment in anyone’s life.

Bake’s Sawabali or Sawabullah was an other-wordly man, his son said. He knew 12 languages, sheltered Hindus and Muslims in his home at the time of the Shongram, meaning the 1971 War of Liberation, went out and spoke to the Pakistani soldiers in Urdu or Hindi or whatever language it was, till they were gone. ‘Just today Nripendrababu came and he sat here and was talking about Abba and weeping,’ he said. Nripendrababu, Umeshbabu, Ashwini Nath—all the Hindu families who were given shelter in their house in 1971. He had brought back some money from his job as a sailor, and also from his stay in London, but he also gave it all away. Gave food to so many. Gave home to all sorts of fringe people, the blessed and the mad ones. ‘Abba had brought with him one Koilkattai Pir.(a pir from Kolkata, possibly because their ship would dock in Khidpirpur, Kolkata.) The man was so mad, he could bite into hard iron and bamboo. Then there was one Hoq Bhandari, who went round and round crying “Hoq Bhadari Hoq Bhandari!” They lived for 12 years in this house. Called our Amma Ma. They were like children. When people teased them, they went to Amma and cried.’

As Anfur Ali remembered things, others around him also started to remember. A collective memory of joy and pain began to rise and fill up the space of the courtyard of that humblest of houses, as the azaan of Maghreb (call to evening prayer), was heard from the mosque nearby. Then from another mosque in the distance, then from another further away. It was so beautiful. I folded up my laptop, packed my things and rose to leave.

‘”Uchana dolane boshi, ki koro mon parobashi re/ Amar parobashi, oshar ei jibon re” (Sitting in that lofty house, what to do, O exiled mind?/This exile life has no meaning at all.—Abba used to sing this song. After he lost everything and went to Companyganj in search of work, he would sit and sing this song. He badly missed his close ones whom he had left behind.’

Ambarish Datta and Anfur Ali sing and talk as the latter walks with us to the main road from where we will take a vehicle to Sylhet