Sushoma Mashima, a Keeper of Songs

She can hear what we can’t because she knows what to listen out for. She can also listen to absent sounds, because she knows where they were supposed to be. I went to meet her with her with the disembodied voices of Arnold Bake’s seamen, plucked from the sound archive. On 15 January 2018 Ambarish Datta and I went to meet 88-year-old Sushoma Das, for she is someone who keeps songs in her body. We knew she would hear more in those recordings than most people we know.

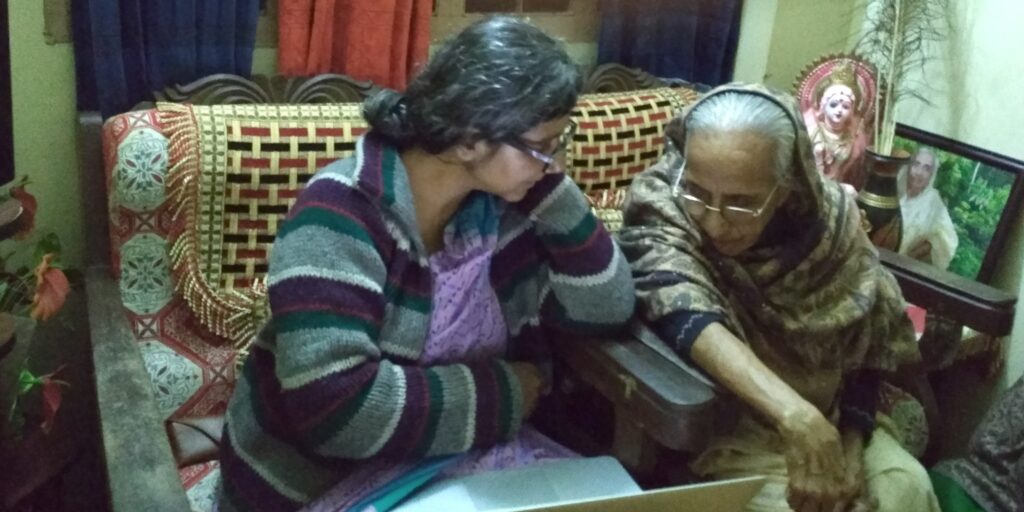

Sushoma Das in her home in Sylhet in January 2018

I first met Sushoma Das in 2006, through Ambarishda, whom I also met for the first time that year. I have gone back to Sylhet many times since and recorded Sushoma Mashima (mashima meaning aunt) and many others over the years, while Ambarishda has become like family. In 2012 we brought out an album of field recordings of Sushoma Das and Chandrabati Roy Barman (1931-2014) . Sushoma Mashima has the strongest voice and a phenomenal memory even at this advanced age; she stands like an old banyan tree in our present time of feeble voices and callous oversights. On this day in 2018, when I was visiting Mashima with Bake’s recordings, she sat there in her room, frailer and thinner since the last time I saw her in 2015. Besides Ambarishda, and the Sylheti folk song collector and researcher-writer Suman Kumar Dash (who came in late), her daughter Bashona, sons Prashanta and Probir, and a neighbour, Madhab Chandra Das, were present in the room, while other family members walked in and out with water, tea and sweets. I sat on a chair next to Mashima and play her Bake’s sailors’ songs from my laptop. The noise on the surface of the cylinder envelops the voice, it is not easy to listen to the song, especially from the speakers of the laptop, what with outside noises of people talking, work in the kitchen and vehicles on the streets below and beyond. Yet Mashima became immediately alert. In fact, it wasn’t just Mashima, but everyone in the room seemed able to listen to something that we could not hear, as they listened with their insider knowledge, as we have seen in many other places.

I begin by playing two songs recorded on Bake India II Cylinder 341 A, recorded on 1 April 1934. They are credited to Sayed Ali, sailor from Hirpur (Comilla p.o.). One is labelled in the archival note as ‘Hridoy jole’ (The words go, ‘Elo re basanta, hridoy jwole’, meaning, it is springtime and my heart burns). The other has a one-word description, it is called just ‘Amay’. The line sounds like this: ‘Bhuilo na bhuilo na amare’, do not forget me. Sushoma Mashima says each place has its own way of singing, but these were not from Sylhet. I say, yes, that is what the note says. The singer was from Comilla. ‘Wherever it is from, the song about basanta or spring is a biraha (song of separation and longing)’, she says. She is slowly getting used to the sound of the cylinder. Then I play ‘Pranonath bondhure’, sung by Fayazullah, stoker from Damrasari, Sylhet.

Out of the 15 cylinders on which Arnold Bake recorded the sailors on board the Streefkerk, five (nos. 343, 347, 348, 349 and 350) were of Fayazullah. I played cylinder 348, recorded on 14 April 1934, titled ‘O pran nath’, and Sushoma Das was in her element. ‘Shakkhater gaan, shakkhater pod. Radha Krishner milon hoise, miloner pore ei gaanta’ (This is a song of meeting, Radha and Krishna have met and this is song which comes after their union). And then the words began to flow out of her. Mashima recites:

Pranonath bondhu re, bohu dine paiasi tumare.

Kato batshar hoilo gato, ore bondhu

Tilek na herilam tumare, bohu dine paiasi tumare.

Bondhu re, amar moto katoi nari

Ase tumar aggakari

Sheba kore tumake paia, o bondhu re.

Ore, ami noi tor shebar jugyo,

Kun gune paibo tumare, bohu dine paiasi tumare.

O bondhu re, adhore adhoro diya

Srubone srubon mishaiya

Noyone noyon rakaiya

Sudhamrito borishone, o bondhu shushitol koro amare.

Friend, lord of my heart, I have you to me after ages.

Many years have passed, O friend

I have not had even a glimpse of you.

I have you to me after ages.

O friend, so many women like me

Are happy to obey your orders

They serve when they have you for them.

Am I even worthy of serving you?

What gift do I have to ask you for me?

I have you to me after ages.

O friend, touching with lip on lip

Listening from ear to ear

Holding your eyes in mine

Showering me with your nectar of life,

Make me quiet and calm.

These are not the exact words that Fayazullah sang, but it is a variation on the same song. Mashima first spoke the words and then as I kept requesting her to sing the lines, and as she kept saying, I cannot sing these days, amar gola khyan khyan kore, my voice cracks up, I knew that she would ultimately give in. Of course when she sang it was pure gold.

Mashima listens to cylinder 347, labelled ‘Shunu bondo shivsarane koi’. Even before I play the song, I tell her the name and she says that there is such a song indeed. ‘Shuno bondhu tumar sricharane koi,’ she corrects me.

Bake’s notes were clearly flawed in many places, or at least in the way the notes have come down to us, there appear to be many errors. So, for both Ghutia in Noakhali Sadar and Damrasari in Hirpur Bazar, Sylhet, it is likely that he had got the names wrong. Perhaps they told him something in their Sylheti or Noakhailya way, and he wrote down what he heard. The sailors were in all likelihood unlettered and so they would not be able to spell the names or the names of their villages for Bake. Again, this is only a speculation based on thin evidence or plain common sense. ‘Shunu bondo shivsarane koi’, that line makes no sense whatsoever. I played the song and then Mashima began to speak the words, and out flowed a whole song.

Shuno bondhu tumar sricharane koi

Mor ki loy re bondhu, tumay chara roi

Bondhu re, jothay tothay jao tumi, ami chaiya roi

Koite na’ri shoite na’ri, kuno jwala shoi.

Bondhu re, tumar monete mon mishaiya moner dukkho koi

Amar mone shadh re bondhu, tumar dashi hoiya roi

Shuno bondhu tumar sricharane koi

Bondhu re, tumi na korile doya ami jabo koi?

Tumi bine Radharaman parobashe roi.

Friend, see, I beg at your feet.

How, my dear, can I stay without you?

Wherever you go, Friend, I look your way

It is hard to tell and hard to bear, the suffering this brings.

My Friend, I meld my heart with yours and tell you my pain

I wish in my heart to serve you all life long

Friend, see, I beg at your feet.

O Friend, if you do not care, then where shall I go?

Without you, Radharaman feels banished from his land.

‘That’s how the Radharaman song goes, but this singer has mixed up the verses (ultafalta korse) and has also not signed off with Radharaman’s name as the rosit (রচিত, which is a very Sylheti way of saying writer/composer and it is utterly untranslatable),’ Sushoma Mashima said. She sang the song her way, rhythmically different from the recording. I asked her about the rhythm in the recording and she said, he is a singing the song as a dhamail, a dance of Sylhet. Can you sing your song that way? I asked. Can I? she laughed. Of course, she could. She sang a few lines of the song as a dhamail.

Listening together. Mashima, her daughter Bashona and I. Sylhet, 15 January 2018.

On 2 April 1934, his second day of recording the sailors, Fayazullah of Damrasari, Sylhet sang a song which began with the words ‘She dukh’. This is the song which had made me think of Ranen Roychowdhury. As the song plays, Mashima and her son and daughter all listen with rapt attention and then she starts to speak out the words.

Caption: Mashima listens with her son Probir and daughter Bashona

সে দুখ কইবার কথা নয় গো বলিব কারে?

যার অন্তরে জ্বালাপুড়ায়, সখী,

সে নিবে কি অন্য জানে?

সে দুখ কইবার কথা নয় গো বলিব কারে?

Shey dukh koibar katha noy go bolibo kare?

Jar antore jwalapuray, shokhi,

Shey bine ki onyo jane?

Shey dukh koibar katha noy go bolibo kare?

It is such an unspeakable pain, who can I tell?

She whose heart is scorched and scathed, my friend

Can anyone but she know?

It is such an unspeakable pain, who can I tell?

They are listening together and everyone in the room in chipping in words. This is such an informed community of listeners! ‘Keu ba parobashi,’ one says. ‘No no, it was bonobashi,’ says another. ‘Keu hoitechhe shmashanbashi, or was it deshantori?’ ‘There is also keu ba bhikharini.’ They hear different things, but basically variations on the idea of the dejected, almost destroyed lover, who is either leaving home, or is beggared or is choosing to stay in the smashan or crematorium or is going on exile. Finally, we come to the word Deenoheen. Is it a song of Deenoheen, Deenoheen, the folk poet? Or is the poet describing himself as deenoheen, one stripped of all riches, ready for total submission?

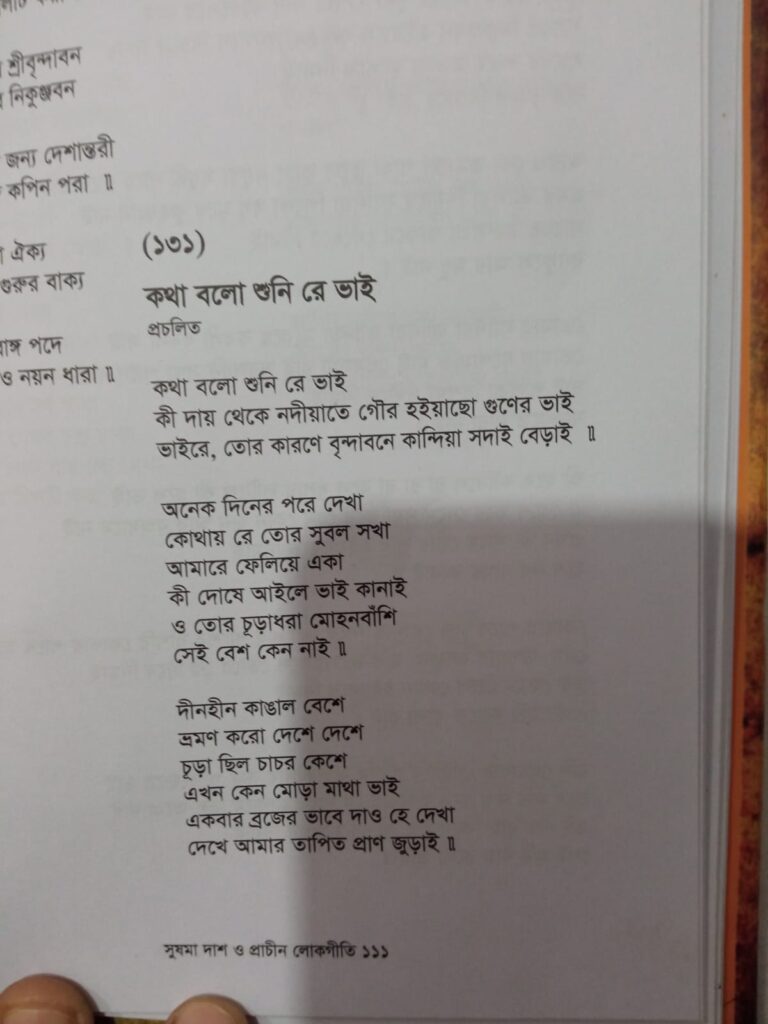

A young student of Sylhet in London, Azimul Raza Chowdhury, who is very close to Sushoma Das and her family, sent me this page with an anonymous song which has the word ‘deenoheen’ in it. Not as a name but as a state of being. ‘শাহ আবদুল করিম এক গানে বলেছেন আমি দীনহীন তুমি বাসিয়ো না বিন।‘ দীনহীন এই ক্ষেত্রে সম্ভবত স্রষ্টার কাছে কাতর হয়ে নিজেকে তুচ্ছভাবে প্রকাশ করতে গিয়ে ব্যাবহৃত হয়েছে।

Probir Das, Sushoma Mashima’s son, recalls songs in which poets use the word deenoheen to describe their state of ultimate devotion. He starts to sing the song for which Azimul had sent me the words.

We listen together to ‘Shey dukh koibar katha noy go bolibo kare’, cylinder 343, sung by Fayazullah. Then Probir sings ‘Katha bol shuni re bhai’, a song about Chaitanya, the 16th century Bhakti saint of Bengal, who renounced home to reach his god, and sang the Name (of god) as his way of devotion and love. From Arnold Bake’s ship, through the temperature-controlled space of the archives in Berlin, to Mashima listening to Fayazullah’s song, to her son singing songs learned from the mother—we have crossed many borders of time and space, backwards and forwards, in the course of that one evening.

Ambarishda had posted a beautiful song of the composer Deenoheen on Facebook recently and I asked him to send me a copy. Here it is.

Ambarish Datta who is also deeply knowledgeable about songs of Sylhet sang this song recently, which is a composition of the folk poet of Sylhet, Deenoheen (don’t know where exactly he was from) and goes thus: Tumi thako bondhu hiyaro majhare (Stay friend in the core of my heart)

Ambarish Datta with Sushoma Das’ son Prashanta in their home in Sylhet on 15 January 2018

We listen to cylinder 350, recorded by Bake on 15 April, which is described as a ‘sari gan’ (boatmensong). The words go ‘Sarati jibono gelo morome mojiye’, it was sung by Fayazullah. Is it a sari gan? I ask Mashima. No, Mashima says. This is a ‘Monoshiksha dehotottwo’ song, she says. A didactic song about ways to cleanse the soul.

I also played Cylinder 351, the song that Sawabali had sung on the last day of Arnold Bake’s recordings on the Streefkerk, the song with which we had gone searching in Harikalash and had finally found Sawabali’s sons in Alapur

Mashima and others in the room listen to Sawabali’s ‘Je din jaabe akher tori’. Again, this is a ‘Dehotottwo’ song, Mashima tells us. ‘Jokhon asbe shomon jari, shob jaabe tolaiya’. A song about the final crossing, the final day when all things will cease to matter. ‘Monshikkha go ma,’ Mashima says. These are lessons for the soul. ‘Bujha jaay, bujha jaay na’—I get some of it and some I can’t. Then she comments: ‘Onek puran sur, this is an old old melody’.

Then a lot of discussion followed on the question of the rosit, the songwriter, and how people sing without naming the rosit. It started with one of Fayazullah’s songs. Sushoma Mashima is clearly troubled by such matters. She talked about a song she had heard someone sing, crediting Radharaman, while it was in fact a song of a rare woman composer of Sylhet, Rupmanjari.

Mashima expresses her disappointment with the words of songs as they are sung nowadays. She cites examples, then sings, ‘Haro go, Bridaban aaj preme bheshe jaay’, singing her bhonita to Rupmanjari. Her sons beat the rhythm and daughter Bashona joins her voice.

Bashona Das lives under the shadow of her mother, as do all of Sushoma Das’ children. Mashima is such a strong personality, after all! Bashona had visited Kolkata with Sushoma Mashima in 2011 to perform at the Jadavpur-Shaktigarh Baul Fakir Utsav, a folk festival organised by friends, including us. Mashima had also joined The Travelling Archive’s website launch at Jadavpur University on 11 January. I thought it would be interesting for us to see Bashona Das dance and sing at the launch—such a joy to watch her. Moreover, she is dancing the dhamail here, the dance we mention above, in the context of the song Shuno bondhu tumar sricharane koi.

The dhamail is not meant to be danced alone. But here as Bashona Das is singing and dancing, with her mother sitting behind her and providing support, we have to imagine the other women and listen to the chorus in that solo voice. 11 January 2011.

From the Rupmanjari song, the conversation turned to the topic of women composers. Did your mother Dibyamoyee compose, I asked Mashima. She might have written one or two songs, wedding songs and so on, but they are not so important to me, ami oto gurutto dei na, Mashima replied. ‘But my father Rasik lal wrote several good songs.’ Then Mashima and her children and Ambarishda and Suman Kumar Das all started to talk about the songs of Rasik Lal Das. Finally, Mashima’s third son, Prashanta sang a composition of his grandfather.

Sushoma Mashima mentioned a composer Rukmini in the context of women’s songs and sang a few lines of the song. Then she was out of breath. Then Prashanta sang ‘Amar bhanga naiyer naia’ (sailor of my broken boat)

Prashanta had quite got into the mood of singing that evening and he sang a song he had learned from his mother, ‘Shudhu bhakti korle’. There was a touch of regret in Prashanta’s voice. ‘I don’t get much of a chance, ami to shujog ujog pai na. Mone iccha hoy je di ekta gaan kori.’

Mashima was getting quite impatient about journalist-writer Suman Kumar Das; why is he not coming, she kept asking. Then he came.

Suman Kumar Das works for a national daily, while also being a prolific song collector and writer. Here he is with Ambarishda.

Finally, when she was sufficiently relaxed, Sushoma Mashima sang the Rukmini song, concluding though that the songwriter might not have been female. They deliberated on the ambiguity of the matter.

How did Mashima learn these songs? I asked her. Just by being in an environment where music filled up every bit of life. ‘Luker mukhe shune shune,’ she said. By listening to others. Then she sang the Rukmini composition. ‘Prano bondhu re dile dekha bohudiner pore’.

When we were leaving, Mashima came to the door as always and as I touched her feet she said, ‘Will I see you again?’ She says this every time we meet.