Naogaon 3. November 2018

The two years between the last trip and this one was spent trying to find out more about the singers and the songs from Naogaon. And, I was looking for them in Mansooruddin’s books and in the archives, in old photographs and by studying the archival notes over again. It is then I came across the name of a place in Naogaon which might have been where at least one of the singers came from. The name was next to the name of Dijan Fakir. Rather, there seemed to be several names of seemingly one place. Or, possibilities of names. At least there was something to go looking for. The overriding question for me continued to be, who was Jaura Khatun Khaepi? Who was the woman who had sung for Bake?

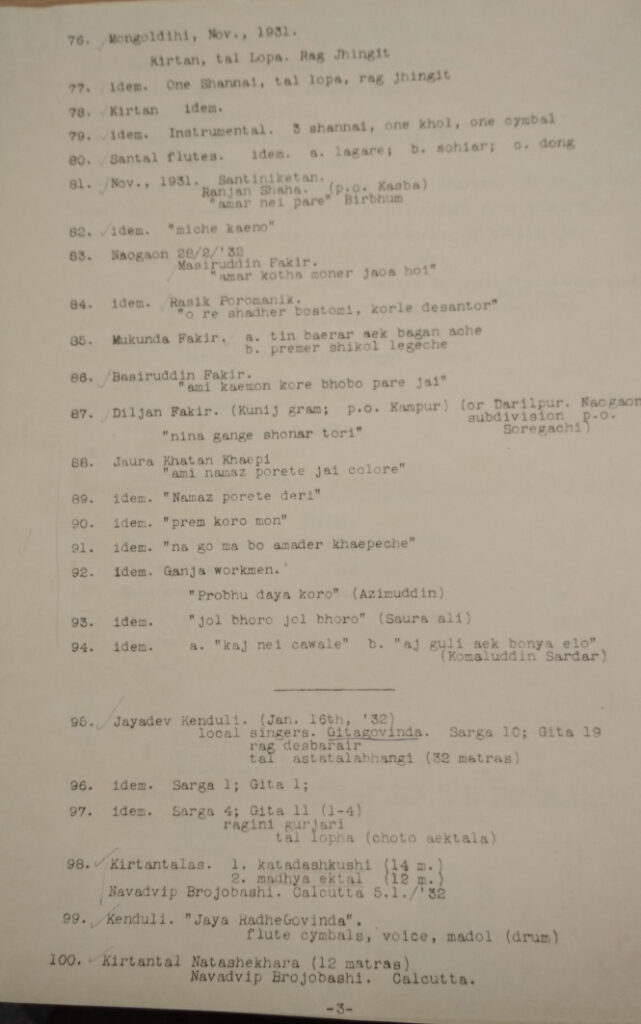

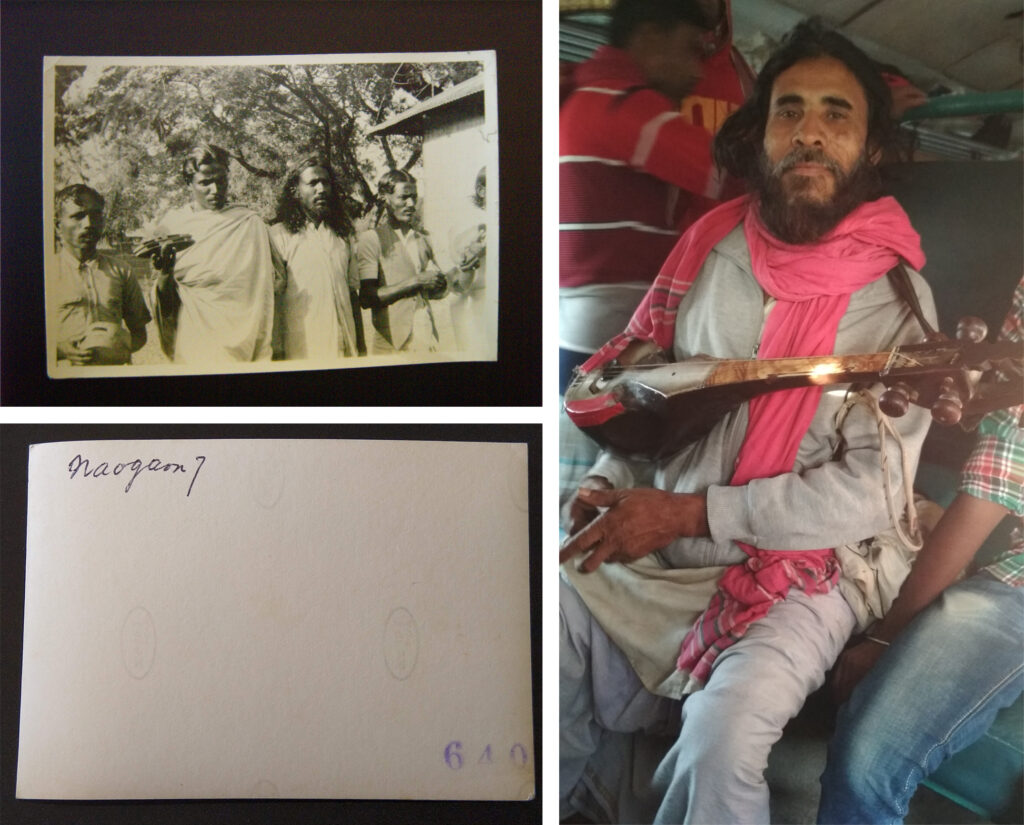

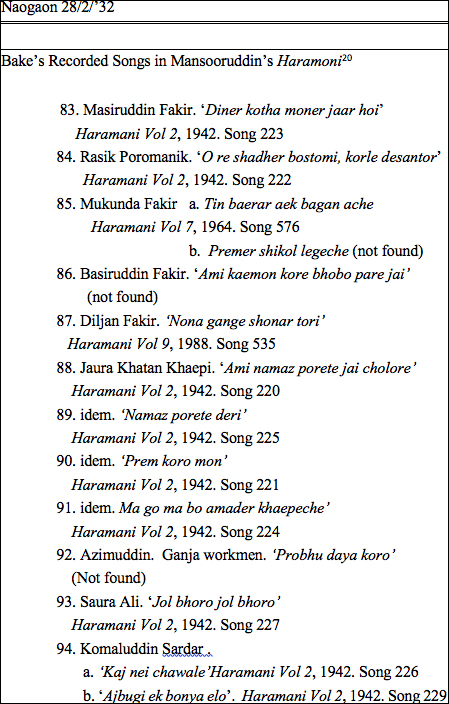

A page from the same archival note found with the British Library, Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv and the Archives and Research Center for Ethnomusicology, Gurgaon. See note for Bake India II, cylinder no. 87, against the name of Diljan Fakir.

In November 2018, I was in Rajshahi again. As I was saying, I had finally noticed the names of Kujij gram; P.O. Kampur. (or Darilpur, Naogaon subdivision, p.o. Shoregachi) against the name of one of the singers, Diljan Fakir, who had sung the song ‘nina gange sonar tori’. So I asked Uday Sanker Biswas, my folklorist friend from Rajshahi University, if he had any idea about these places. Uday said, the names were probably not correct, but they suggested other names to him, and one place was close to his in-laws’ house, and we could go looking there. Shoregachi was likely Shailagachi, he said. Darilpur could be Dariapur, he thought.

On 25 November 2018, I went by train to Rajshahi from Dhaka, my recorder receiving what sounds it found on the way.

On the 26 November 2018, Uday Shanker Biswas, Shaikot Arefin—both teachers of Rajshahi University—and I went to look for Diljan Fakir in Shalagachi. Uday charted out the route, so from Rajshahi we would take the train to Ishwardi and then go to a Dariapur and from there wherever the road took us. The train went through the fog, towards Abdulpur, halted and we got off and ate luchi and alur tarkari while the engine moved to its tail. Then we got on again and the train started to go towards Ishwardi.

I was sitting by the window looking out, as the train started to move. At one point I turned my face and was taken aback by what I saw. I was carrying Arnold Bake’s images from Naogaon with me, not only on my computer but also in the recesses of my memory as I had seen them so many times. Suddenly it seemed to me that his photos had turned from black and white to colour.

Arnold Bake took a series of photos of the Naogaon fakirs. This one was marked Naogaon 7. The man sitting opposite us on our train to Santahar said his name was Ataur Rahaman Chishtia or Shah Alom. His home was in Lalpur thana of Natore district, he said, but he goes roaming and singing and that is what he does for a living. Slowly we talked more and he sang for us too. He said he was going to Ishwardi to fix his instrument, I asked him if he would come with us on our trip, he said he had work to do, I asked if it could wait for a day. Other people on the train said, how can he go with you? He has a living to make by singing. So then we reassured them and said that if he came for the day, we would certainly take care of his earnings for that day. At which he agreed to come with us. Then he said, best would be for us to get down at Akkelpur. We could then set out on our journey.

Ataur Rahaman Chishtia sings. Milon hobe kotodine, Char peyala hrid komole, Ami opaar hoye boshe achhi, all songs of Fokir Lalon Sai. And in the second clip, he talks about how he came into this spiritual line of music.

At Akkelpur, we met one of Uday’s students and went to her house to freshen up. Then we hired an auto rickshaw and went in the direction of a place called Dariapur. Perhaps it would be the Dariapur we were looking for? Now Ataur Rahaman was our guide. There was someone he had in mind, a singer, whose house we went to, but the man was not at home. We could find him in Badalgachi, we were told. All these places were within close proximity. So next we went to Badalgachi, to a kind of club where local singers meet. Here we met several people, who explained to us that this was most probably not our Dariapur, but the best place for us would be Shailagachi. (Perhaps that was Arnold Bake’s Shoregachi?) Meanwhile, the singers of Badalgachi also listened to the Bake recordings and sang some songs for us.

A plaque in the wrong Dariapur

Aroj Ali of Badalgachi Shilpi Goshthi sang for us.

Aroj Ali sings

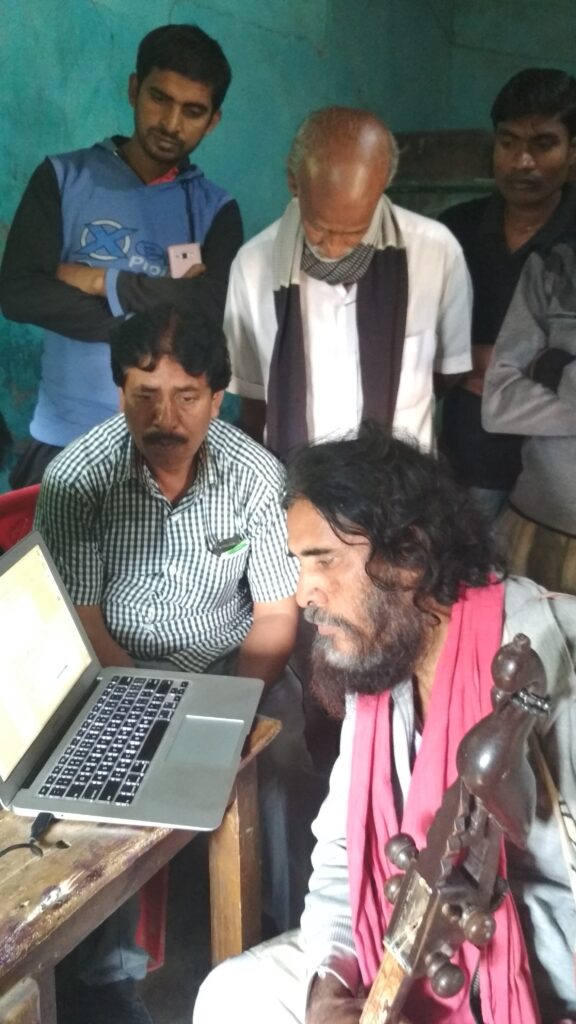

Listening in Badalgachi

Next stop was Shailagachi, via Pintur More. There were some comic moments along the way. At Pintur More, we asked for directions to the house of Rahim Chand. Why Rahim Chand?

Map of all the places we went to in Rajshahi in search of the Naogaon singers of Arnold Bake. Includes image of Hardinge Bridge by Sarker Protick. Map designed by Purba Rudra

It was Ataur Rahaman Chishtia who suggested that we go to the house of Rahim Chand Dewan, a famous singer of Shailagachi. This was a family of musicians. Rahim Chand was dead, also his eldest son, singer Abu Bakkar. But Rahim Chand’s widow, Bilkis, who was also a singer, could know something. Rahim Chand would be about a hundred if he was alive. So he could have known Bake’s singers.

One of Rahim Chand’s sons is the famous flautist of Bangladesh, Jalal Ahmed. Yet economically, they are people who live on the margins of society.

Finally, we reached Shailagachi. The sign board had something interesting inscribed on it: an NGO named Moushumi!

Ten-year-old Ahsan Habib takes us to the house of Rahim Chand Dewan. We reach the door of Kabari Dewan.

Kabari Dewan’s tin door was half open and we went in. This was the house of Abu Bakar Dewan. He had two wives, Kabari was the younger one. Is your mother-in-law in? Ataur Rahaman asked. No, she is in the other house, she replied. Can you call her? I don’t have her number, she said. There was clearly some tension between mother and daughter-in-law. Never mind that. Kabari’s voice was husky. Her face was a little swollen. She said she had only just come home from a night-long soiree.

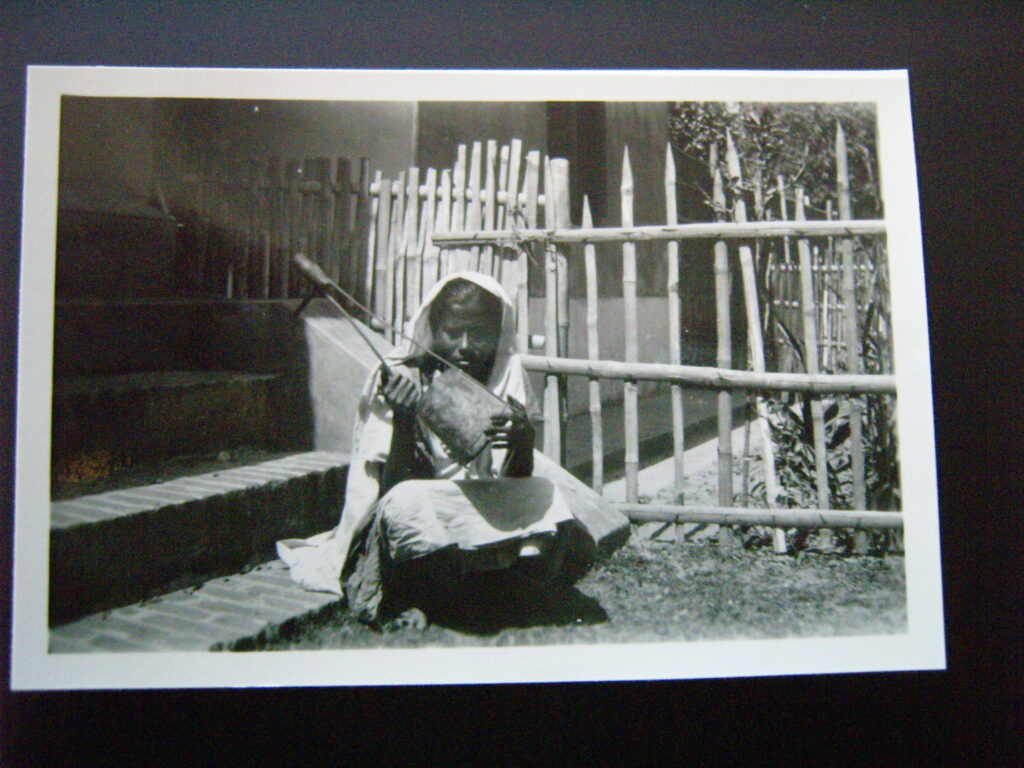

The Naogaon Fakirs Arnold Bake had recorded were all men, except for one fakirni, Her name was Jaura Khatun Khaepi. Jaura? Johura? I had her image from the archives, I also had her voice. Arnold Bake had specifically mentioned her in his letter to his mother on 2 March 1932. I had song collector Mansooruddin and author and civil servant Annada Sankar Ray’s reminiscences of her, but who exactly was she?

Photo of photo, taken when I was working on the Arnold Bake Collection in the Special Collections section of the Library of Leiden University, in 2015.

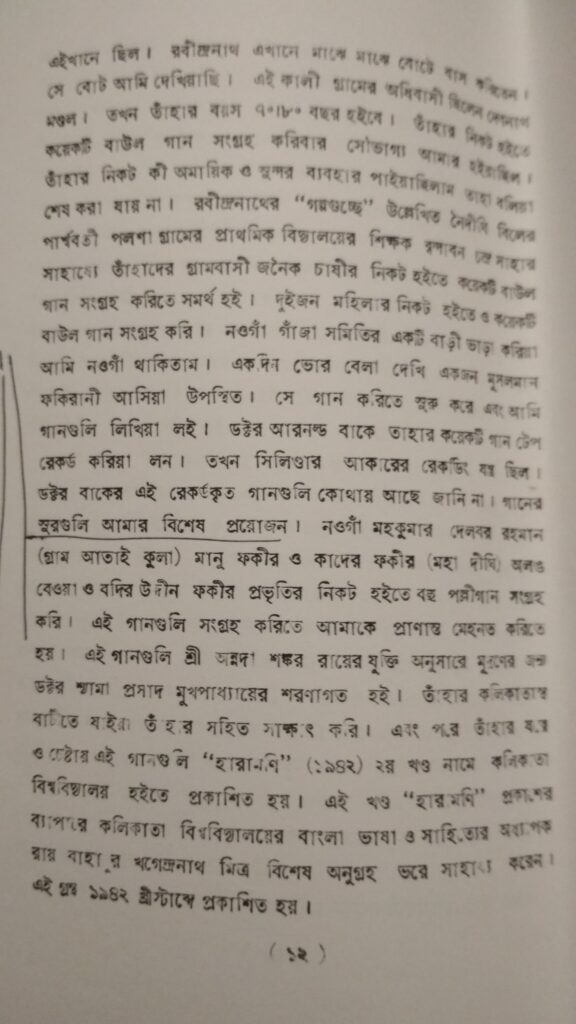

Page from Mahammed Mansooruddin’s Haramoni, Vol 8. (Dhaka: Bangla Academy, 1976)

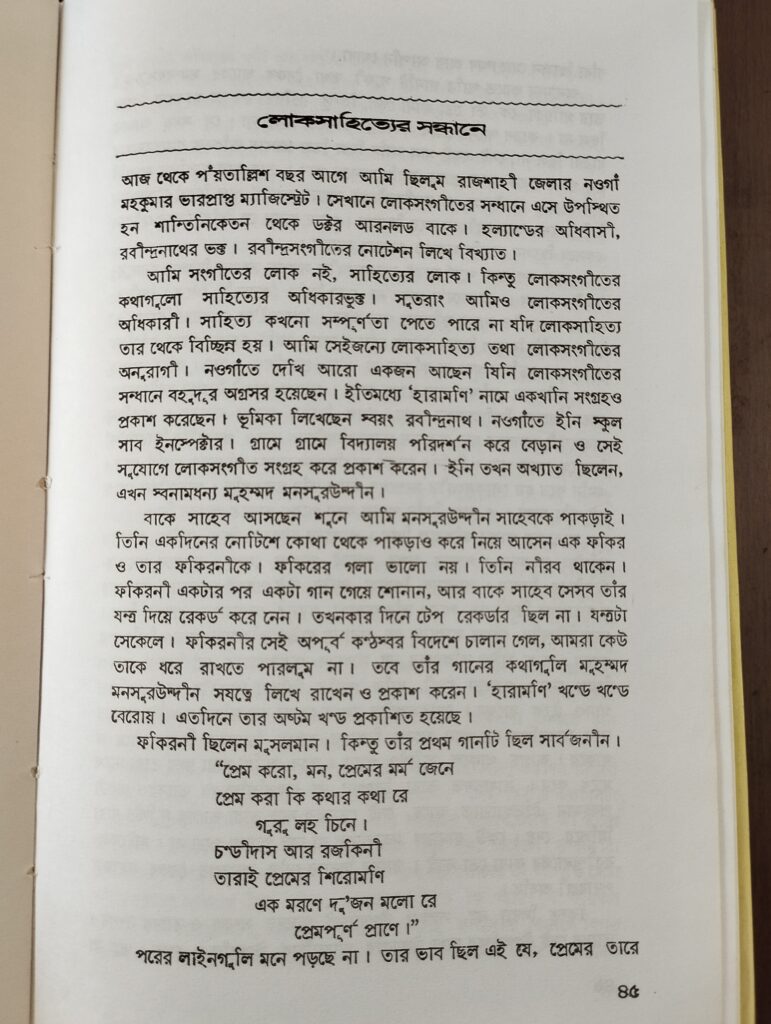

In 1978 the late Bengali poet and essayist, also a civil servant in British India, Annada Sankar Ray, published a book Lalon O Tanr Gaan on Lalon Fakir, the famous nineteenth century mystic poet of Bengal. There is an essay in the book entitled Loksahityer Sandhane (In Search of Folk Literature) which starts with the author reminiscing about an incident which took place ‘about 45 years ago’, which must have been 1932, when he was posted as the sub-divisional officer in Naogaon. division of Rajshahi district in undivided Bengal, now Bangladesh.

‘There arrived one day a man from Santiniketan, in search of folk songs. Dr Arnold Bake, Dutch citizen, admirer of Rabindranath Tagore, who was famous for his transcription of Tagore’s songs. . . In Naogaon there was another man who had come a long way with his collection of folk songs and who had already published an anthology of these songs, Haramoni [Lost Jewels], with an Introduction by Tagore himself. He was a sub-inspector of schools in Naogaon. While he went about the countryside on his inspection duty, he also collected [texts of] folk songs from people. Not many knew of his work then, but today he is the famous Mohammad Mansooruddin.

‘When I heard of Bake’s visit, I put Mansooruddin on the job. Within just a day he got hold of a fakir and fakirni; who knows where from? The man’s voice was not great, so he was mostly silent. The woman sang one song after another and Bake saheb recorded them with his machine. There weren’t any tape recorders in those days. Bake’s instrument was old-fashioned. The beautiful voice of the fakirni got packed and sent abroad (the precise word Ray uses is ‘chalaan,’ which means invoice and thus conveys a sense of transaction. Her voice got chalaaned, Ray writes). We could not keep her. However, Mahammed Mansooruddin wrote down the songs and later published them. Haramoni is being published as volumes and recently the eighth has come out.

‘The fakirni was Muslim. But the sentiment of the song she sang was universal. Prem koro mon, premer marma jene (Love, O heart, knowing what love is worth/It is no easy game/ Learn to seek and find your guru.)’

Mansooruddin’s ‘recordings’ of the songs that day when Bake was making his recordings on wax cylinders are scattered in various volumes of his Haramoni. The song that Annada Sankar Ray remembered all those years later, had appeared as song 221 in Haramoni Vol.2, published in 1942.

Kabari talked about love and loss. The men had moved to the adjacent house of Rahim Chand’s other son, Habibur Rahaman, while Kabari and I had kept talking. Her husband had died only a year ago and then her only daughter too had died. It was her love of music and love for this man that her brought her into this life. Now all is lost, nothing remains, she whispered.

Somehow, for me, the empty corridors of the ganja society office where we had been in 2015 and Kabari’s voice, talking about love, loss and longing began to become one and the same thing. This video, which I used during my Artist Talk for Chobi Mela X in Dhaka in 2019, was made by Sukanta Majumdar, based on my script. The audio recording is mine. Images are collectively authored by The Travelling Archive.

After talking with Kabari I went to meet Habibur Rahaman. Ataur Rahaman steered the conversation—he had indeed become our leader that day.

Habibur Rahaman sings while Ataur Rahaman accompanies him on the dotara. He sang a Lalon song and one of his own.

More importantly, he asked me, why was I looking for these places and people? What would I do with this knowledge? And then I had to think very hard. How to answer such a easily-worded but extremely difficult question? I talked about the flow from Bake’s voices to his own and how with the voices of Bake we cannot know who the people were, but they were real people, like you and me. And so I want to know who the voices belonged to. Just as it is important for people to know who you are, I told Habibur Rahaman.

It was Ataur Rahaman Chishtia, sometimes Uday Biswas, sometimes Shoikat Arefin who were taking the lead on this field trip. I was more the observer. So, in the recording above, you can hear Shoikat ccoming into its frame, announcing that there was indeed a village called Kunij and one called Dariapur too, not far from where we were! Ah, so we had found them then! It was getting late in the afternoon and we would have to return to Rajshahi, so we would not be able to make it to Kunij or Dariapur that day (the actual name of the place is Kunuj, as we would learn on the next trip). That visit would have to wait for another time.