Author: Moushumi Bhowmik

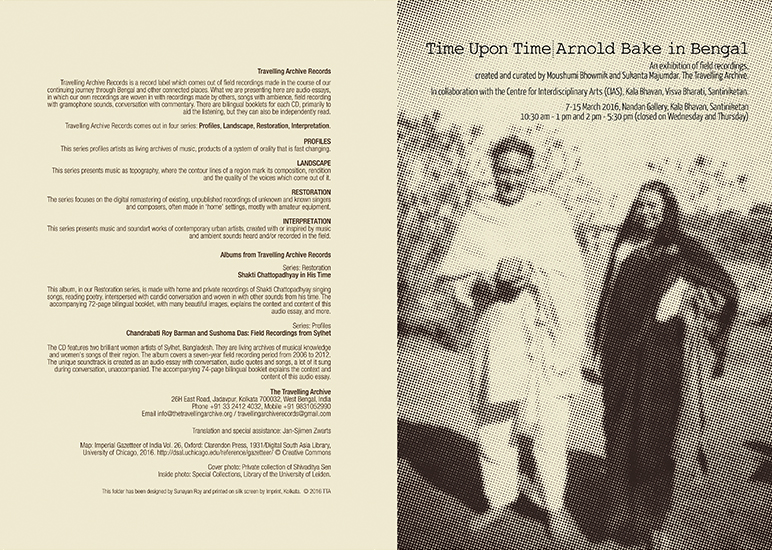

Savitri Govind, who later became the famous Rabindrasangit singer Savitri Krishnan, was 18 when Arnold Bake recorded her in Santiniketan in 1931. She had only just arrived from the Adyar Theosophical school near Madras (Chennai), after Rabindranath had heard her sing there and recognised what a talent she was. Rabindranath heard her sing Muthuswamy Dikshitar’s ‘Meenakshi pe mudam’ and from her song was born the Rabindrasangit ‘Basanti he bhubanamohini’, which Savitri herself recorded.

Years later, in this video recorded in Bangalore by Anjana Dey, who is related to Nandalal Bose through her mother and therefore has strong connections with Santiniketan, Savitri remembered the day Rabindranath had called her over and given her the words of his song to sing and how Dinendranath had tears in his eyes when he listened to the song.

Savitri Krishnan singing Basanti he bhubanamohini in her home in Bangalore in 1992. (Still from video by Anjana Dey)

I tried hard to contact some family of Savitri Krishnan’s but failed. When I found this video on youtube, I contacted Anjana Dey, who lives in Canada, and she was very warm in her response. I asked her if there was more material with her which she would be willing to share with me and also if she knew the whereabouts of Savitri’s family. She said there wasn’t much more to tell except that Savitri Krishnan nursed a wound about never being properly recorded.

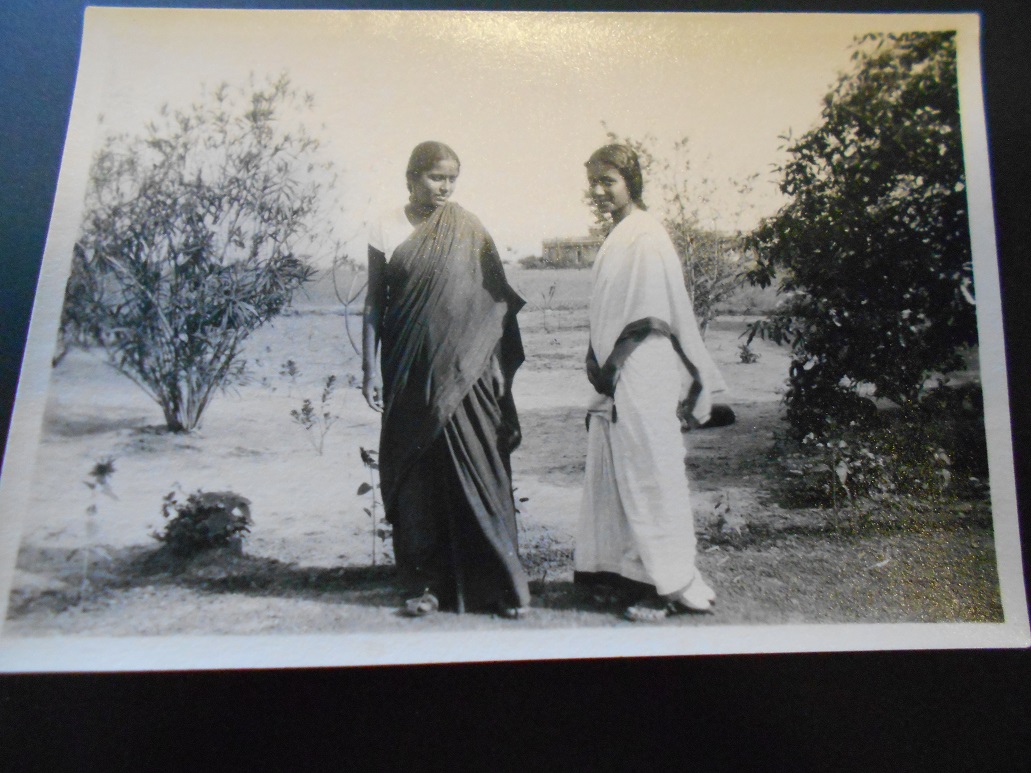

Perhaps she did not know that in the archives of the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv and the British Library her voice as a very young girl lay preserved, never to age. How would she feel if she heard her voice coming to her from her past? What would she think of the wax cylinder recordings? Would she say, oh, but that is so noisy! What would she remember of that day or those days when Arnold Bake had recorded her? Bake recorded several of her songs, which can be heard on the British Library Sound Archives website – Mira bhajans and Kabir and Rabindrasangit and a song of Harindranath Chattopadhyay. Bake also took photos of her.

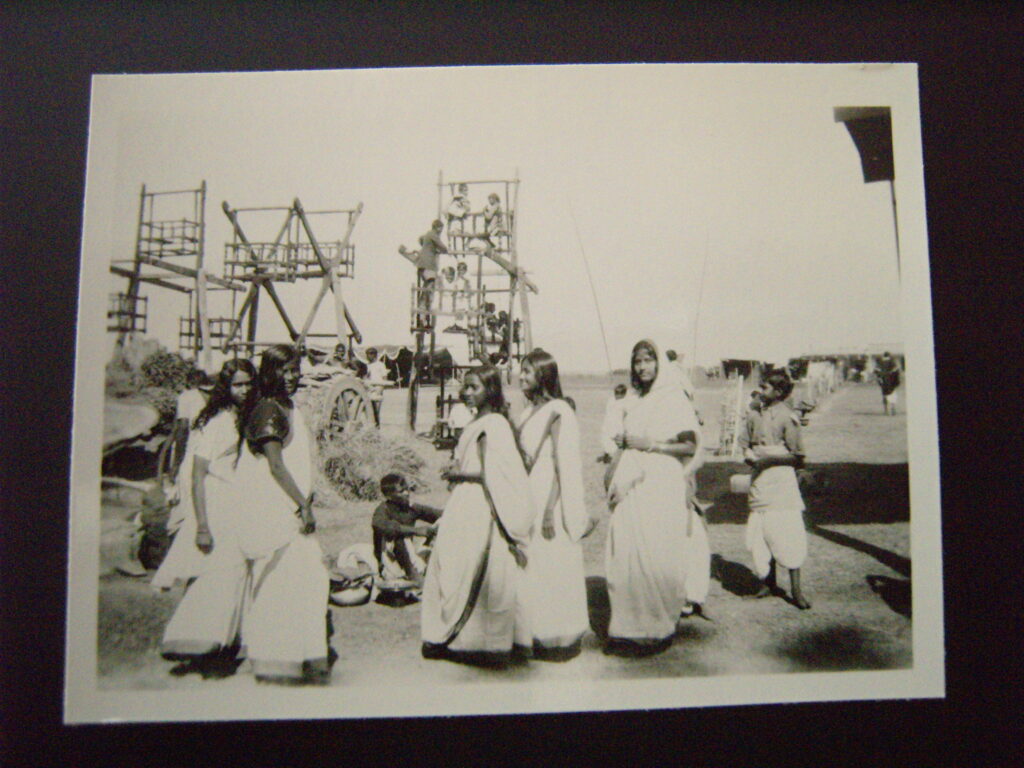

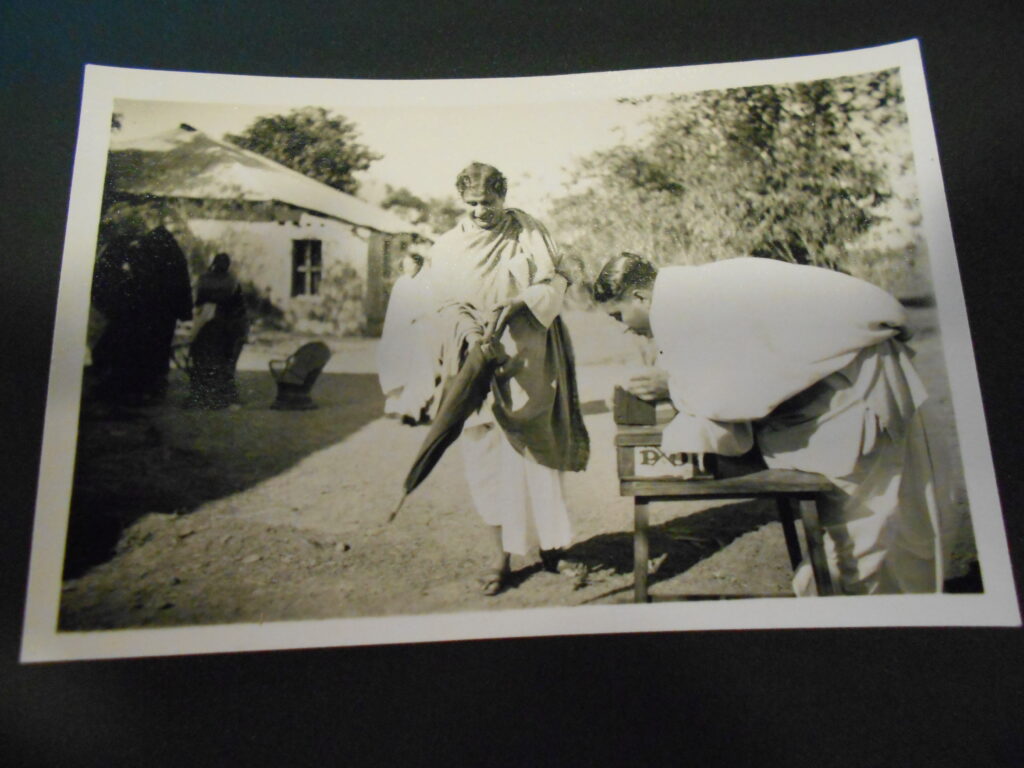

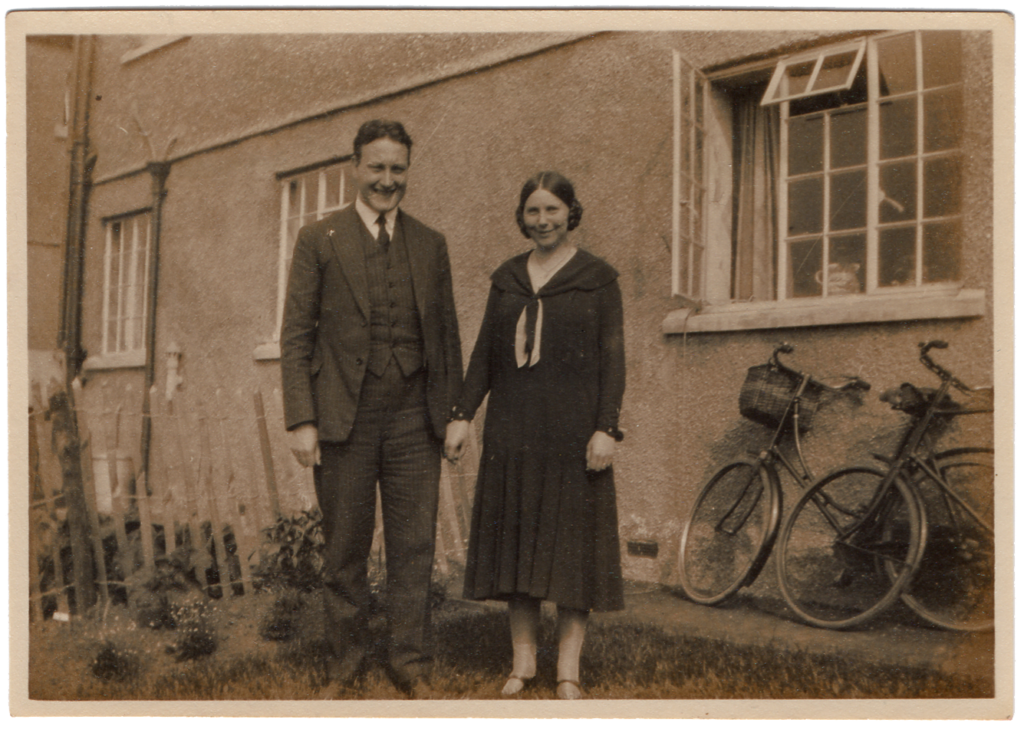

Savitri and friend, Santiniketan. Source: Special Collections, Leiden University Library. I took this photo while working in the library in 2015.

‘The South Indian girl, Savitri, with a friend. S. wears the dark Sari. She’s an enormously gifted and funny child. A while ago, I don’t know if I wrote about it already, she danced with that red shawl not quite unlike a Hungarian folk dancer. We laughed like we hadn’t in months,’ Bake wrote explaining the photo he sent to mother with his letter of 29 April 1931.

She seems to have retained this spirit all through her life. I found a blog note on her and a response I found particularly interesting: ‘I knew her well in Nova Scotia, we started a school for dropouts and exceptional students. Everyone called her Ama. She was a calming influence & encouraged nutrition with an endless supply of fresh fruit for those who sat with her surrounded by her musical instruments. Sage & yet daring. I played tennis with her when she was over 65 & she was always up for adventure. I drove her around in my old car, happily. She loved to sing and laugh.’ (Bruce Maclellan, 9 May 2019)

Santiniketan, 1998. Savitri Govind, Krishnan now, comes hack to the asram. From left to right, Ila Ghose, Suchitra Mitra, Santidev Ghose and Savitri. Not sure about the identity of the children. Photo courtesy: Samik Ghosh.

Arnold Bake was fascinated by the way she sang the ‘Meenakshi’ and he wrote to his mother, ‘this one Sanskrit song that Savitri sung, I would not be able to do that even after years.’ Listening with others to Savitri’s songs on Arnold Bake’s cylinders, including with young scholars of music and practitioners such as Budhaditya Bhattacharyya what was striking to all of us was that, if we didn’t know who the singer was, Savitri’s Mira and Kabir bhajans could be mistaken for a Bengali’s. In my thesis I muse on this and speculate on the reasons for this.

Budhaditya sent these voice messages to me on Whatsapp in May 2021. Around this time, Budhaditya, another PhD scholar at the University of Amsterdam, Mriganka Mukhopadhyay and I were talking among ourselves about Adyar and the connection of the Theosophical Society with Visva Bharati, Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana (which was to become the Indian national anthem) as it was notated and preserved by the Irish Theosophist and musician Margaret Cousins in 1919 and such matters. This was helping me very much to sharpen my understanding of the songs of Savitri Govind that Bake had recorded.

Carnatic vocalist and ghatam player Sumana Chadrasekhar responded on more or less these terms when she listened to Bake’s recordings of Savitri. She recorded herself and sent me her recordings from Bangalore. I am very grateful to Sumana for her perspective.

Sumana Chandrashekar also sent me this photograph.

Sumana explains the meaning of Muthuswamy Dikshitar’s Meenakshi

Sumana explains the particularity of Savitri’s style and the absence of gamaka

Sumana sings Meenakshi me mudam dehi

How Tagore uses the structure of Purvi Kalyani and liberties he takes

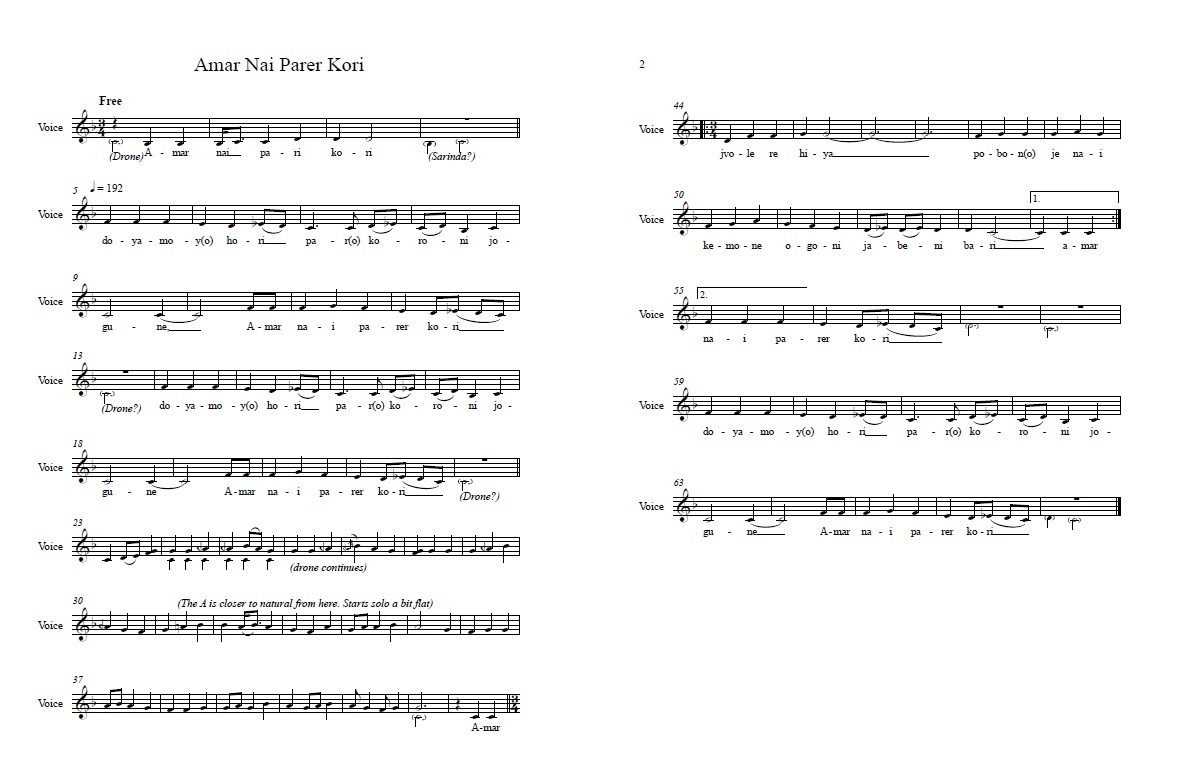

The Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv catalogue describes Ranjan Shaha as Bettelnder Berufssänger from Kasba in Birbhum, which suggests an itinerant singer who lives by madhukori or collecting alms. Ranjan Shaha was a honey-gatherer. Arnold Bake recorded him in Santiniketan on two cylinders (Bake India II/81 and 82) in November 1931, the exact date is not known. He sang two songs, ‘Amar nai parer kori’ and ‘Michhe keno bhabona re mon’, playing the bowed sarinda. Both songs are about making the spiritual journey through life to reach the other shore—the first alluding to the Radha and Krishna story, where Krishna is the rower of the boat on the river of life and Radha is the one making the crossing. The second is a contemplation on the mind and mindless living.

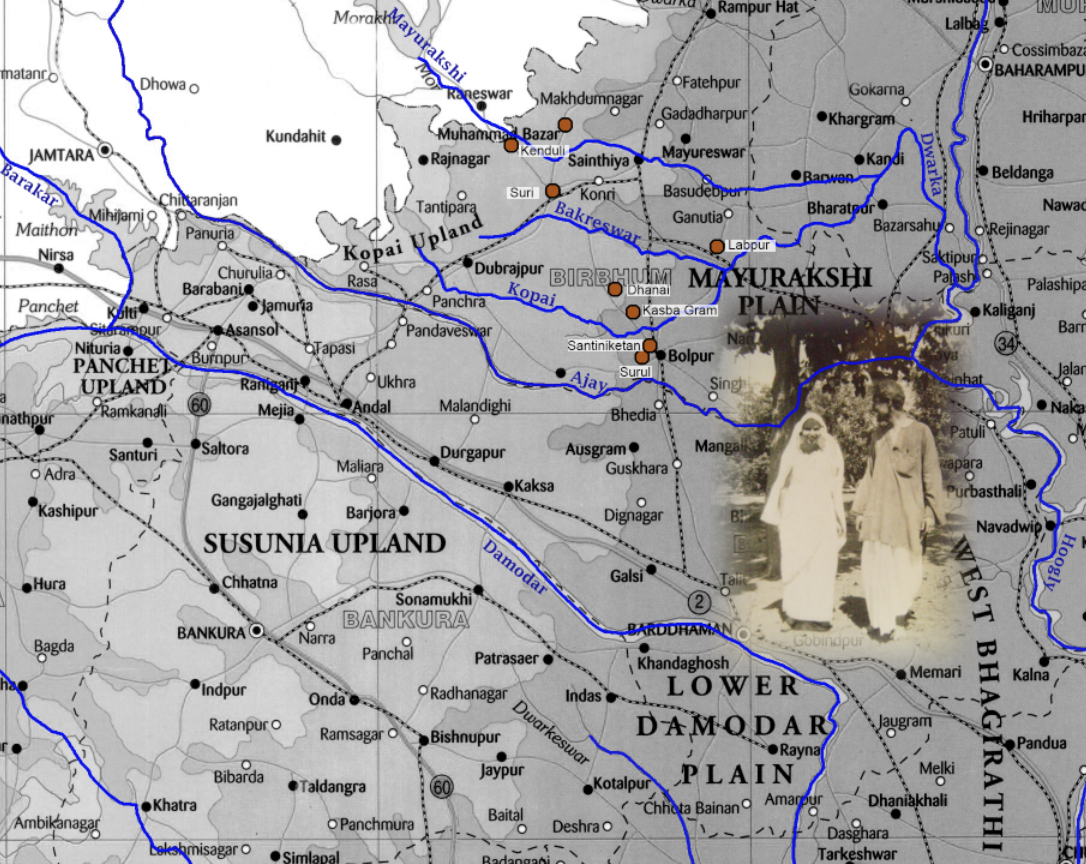

Map showing Kasba, Dhanai, Santiniketan, Suri and Kenduli. Designed by Purba Rudra.

On 15-16 June 2018, I went with my friend, field recordist Soumya Chakravarti, also a teacher in a sense, to Kasba village in Bibhum, about eight kilometres north of Santiniketan, in search of Ranjan Shaha. Soumyada had an acquaintance in the village, Anisur, who worked as a gardener. He became our guide on this journey.

Soumyada and I went by a ‘toto’, a battery-operated three-wheeler, to Kasba. Photos, mine.

There were no trails leading from Ranjan Shaha’s voice to any certain location—no family to be found, no lineage to link him with. However, there was room for plenty of speculation. I made recordings in Kasba, of various people, mostly in conversation. They suggested we go to all sorts of places; everyone had an opinion.

Hairdresser, Kasba. Photo, mine.

Man at hairdresser’s talks about the history of Kasba. The old zamindars who were Sahas, but they lost their fortune and dispersed. They settled near Mama-Bhagne Pahar. Take a bus, get off at such and such place, ask for so an so. Apparently Rabindranath had once come on foot to Kasba. Hard to know how far real and how much imagined these stories were. But the man was a great storyteller. Recorded on my Zoom H2N. 16 June 2018.

On the first day of our Kasba trip, what seemed most doable was to visit Dhanai, which everyone was suggesting. Dhanai was another eight kilometres north, and apparently it was a village of musicians. So, we followed that lead into Dhanai, where we were surrounded by curious listeners as we played Ranjan Shaha’s songs from my laptop. There was more speculation, but nothing concrete. This village could be Ranjan Shaha’s home too. They talked about musicians in their families, fakirs who roamed around, played the sarinda and sang. There was one prominent singer in their village, they said, Akhtar Shah, who could have told us more, but unfortunately he was away on work. Perhaps we could come back another day? Then Anisur, the gardener who grows little things in a plot which Soumyada shares with a friend, proposed a plan. No point waiting for too long. We could come back to Kasba the very next day and Akhtar Shah too could come from Dhanai to meet us. That way we could also have lunch with Anisur’s family, since the next day was the joyous Eid after the fast of Ramzan or Ramadan.

I give the recorder to Soumyada and he conducts the conversation in Dhanai, while I play Ranjan Shaha’s songs on my laptop, simultaneously making a video recording of Soumyada’s recording, with my phone. 15 June 2018.

As planned, the next day we went back to Kasba and kobiyal (singer of kobigaan or ‘a verse-duelling/song theatre genre’) Akhtar Shah of Dhanai came to meet us. He talked about generations of kobigaan singers in his family and also the use of the sarinda as an accompanying instrument. We realised that Anisur was in fact a murid or disciple of Akhtar Shah.

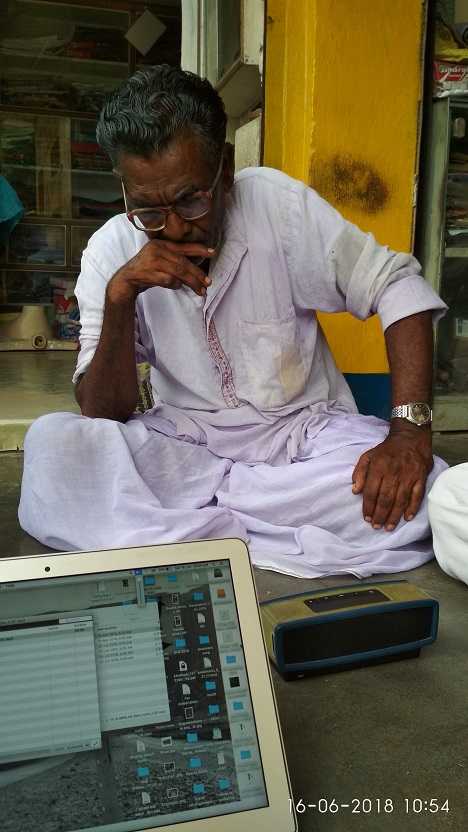

Akhtar Shah listens to Ranjan Shaha. Photo by me.

Akhtar Shah of Dhanai listens, then he starts to talk. 16 June 2018.

We do not know the exact circumstances of Bake’s recording of Ranjan Shaha’s songs; perhaps the singer was passing by his house, perhaps he was a regular in Santiniketan, came to sing like the bee and gathered honey from the asramiks; then flew back to his hive. While such songs certainly coloured the soundscape of Santiniketan, they were more like the breeze that blows over a place but does not stay. The occasional song collector keeps a record of this passing, that is all. Years later, we find traces of that voice in an archive thousands of miles away from the village.

I have tried listening to Ranjan Shaha not only in the field, but I engaged in a kind of ‘collaborative listening’ with the British composer Oliver Weeks and I also sent the recordings to Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur of Mainadal to know what he thought of the song ‘Amar nai parer kori’, especially since Ranjan Shaha sings a story about Radha and Krishna’s leela just as the kirtaniyas of Mainadal did. Within the space of an archive, multiple times and unconnected objects rest side by side without the parts knowing that they actually make one whole story. In my work, I have tried to get a dialogue going between those parts.

Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur and I had a conversation over the telephone on 19 January 2021. The starting point of the discussion was Ranjan Shaha’s song ‘Amar nai paarer kori, dayamoy Hori, paar koro nijo gune’. I asked Nirmalda to tell me the story of Hori or Krishna taking Radha across the river, to see whether what I had written down of Ranjan Shaha’s song—what I thought I heard in that recording, under its layers of noise—made any sense or not. Nirmalda says, ‘Sri Krishna, the boatman, is taking Radharani and her sakhis across the river. The cowherd maidens led by Sri Radhika come to the shore and ask Krishna to take them across. Radha says she has no money. There is some haggling—he asks for sholo ana [sixteen anas make a whole taka], he asks for all. She says I don’t have sholo ana to give, I can at best give half, I can give aat ana.’ Nirmalda shies to tell me details of this story with its erotic symbolism. There are implied meanings, they are talking about both deho (body) and mon (mind), after all. Radha and Krishna are playing with words, he is propositioning to her and she and the girls and the old woman escorting them are dodging his advances with clever retorts. Nirmalda says some, hides some, sings some, and laughs some. I cannot ask very directly either. There is a curtain between us in this exchange, and the listener will hear it fluttering in the breeze in this conversation. ‘Well, I mean, is there anything about bastra or clothes in this story? I thought I heard the word in that other song,’ I ask. ‘Indeed there is,’ Nirmalda says. ‘Sri Krishna says your blue sari is inviting the rain clouds, if the rain comes our boat will sink. You need to take it off. Radharani says, what about your blue body? Can you shed that too?’ Nirmalda says, ‘This is all about leela or divine play, you know.’

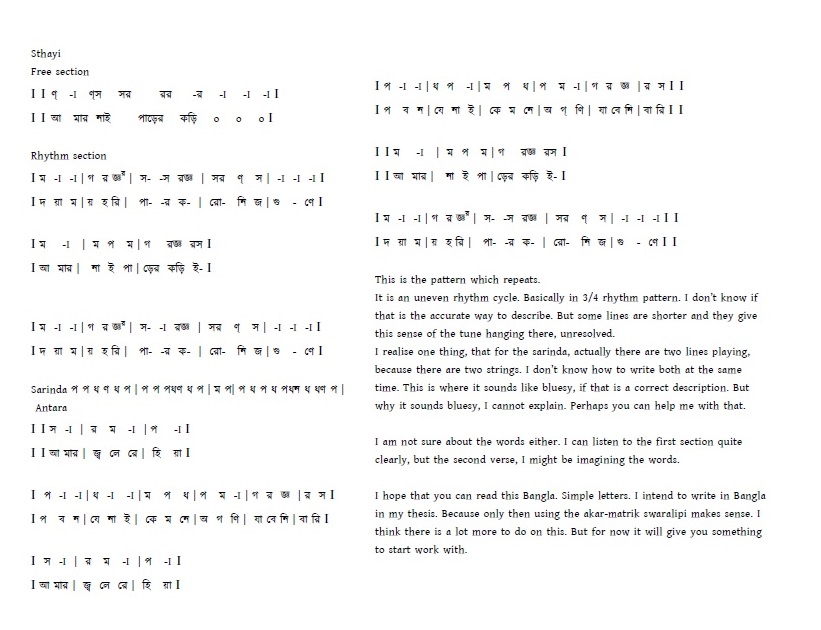

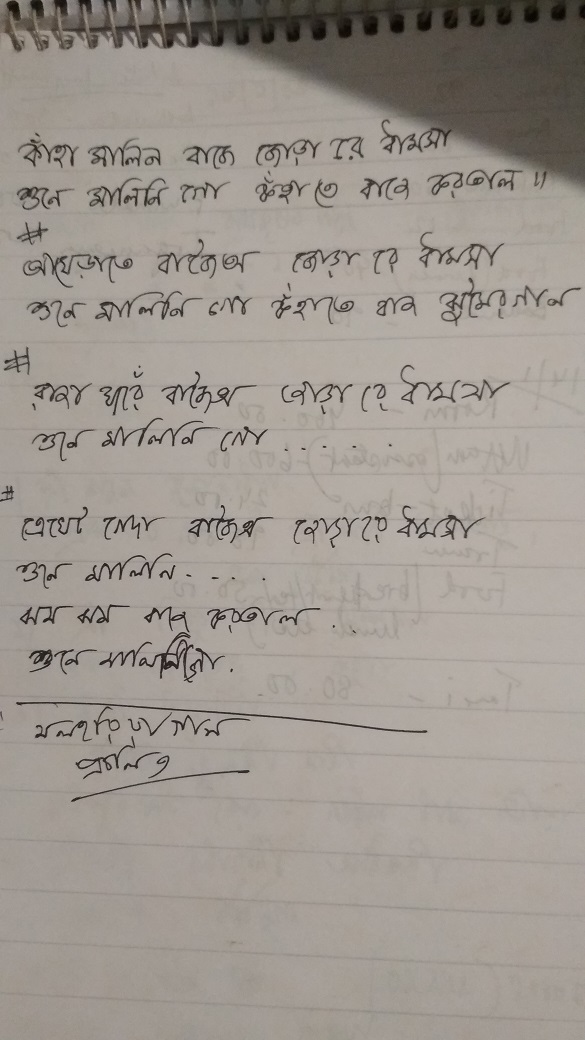

My notation, attempt at writing the words and a brief note to Olly

Sound engineer Abhimanyu Deb had done some noise reduction on the recordings for me, for enhanced listening. I zoomed into the sound of Ranjan Shaha’s songs, trying to write the words. Then I sent a note to Olly. The idea was that we would compare our listenings and our ‘translations’ across media—from sound to text and text back to sound. Moreover, the main thing for me has been to find a face and a place for a song. Where do we go in its absence?

Ethnomusicologists commonly write down their listening as notes and notation. I have very rarely tried out this exercise; I am also not equipped for it. However, Olly Weeks is such an evolved musician and composer, that with him it was easier for me to venture into the world of signs, trying to create other meanings with these old recordings, mixing languages and sonic textures. It is interesting to note how the song shifts from the source and changes meaning as it moves through different places, different perceptions and finds a place in different voices.

Oliver Weeks notates Ranjan Shaha’s songs and sings them too.

Meanwhile, on 16 June 2018, Anisur showed us around Kasba village: the old abandoned house of the zamindars, with trees growing in its cracks. This space inspired Anisur to sing a song for us. Soumyada said, ‘Aare, Anisur! Never knew you could sing!’ Back in his house, the family, dressed in their Eid fineries, posed for a group photo with Soumyada, while Anisur’s son showed off his bluetooth speakers.

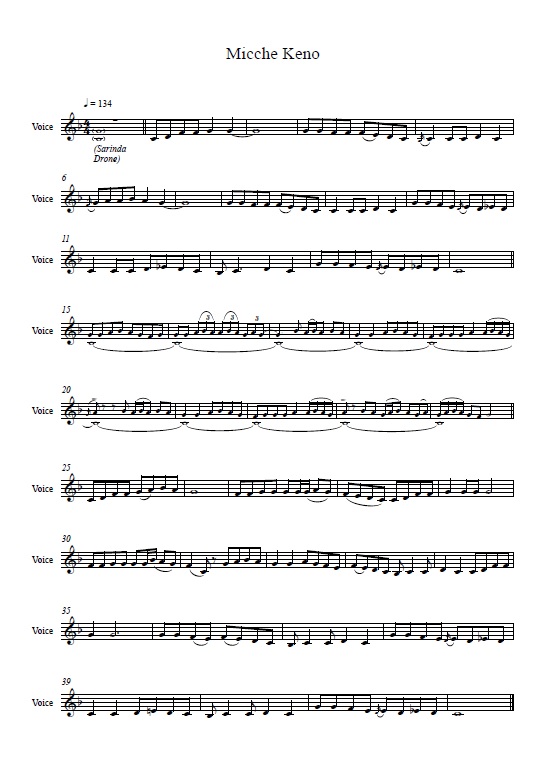

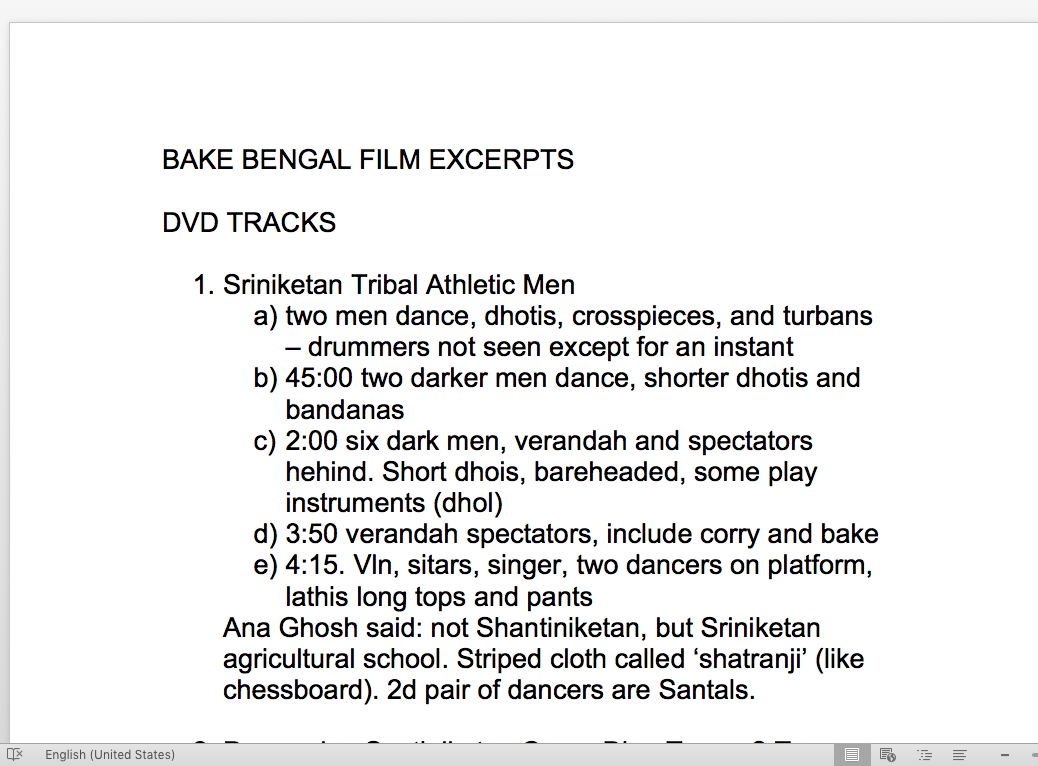

In the Bake cylinder catalogue, Kusum is described as a Bhumij woman from Bankura, who sings a ‘jumur’. Arnold Bake had recorded her in Kenduli on 16 January 1932 (Bake India II, wax cylinder 108). Bake was picking up sights and sounds from the mela. In his letter home after Kenduli he wrote about what he saw there, the kinds of people who had gathered, the entertainers and performers and the devotees. ‘Freaks and outsiders’, bathers in the Ajoy, singers and fakirs, gatherings of sadhus beneath the banyan tree. He recorded all of this with his film camera—bathing scenes, the temple, little shops, baul dancer Ganesh Shyam, Kusum, the Bhumij woman’s dance and her drummer partner. The pair must have attracted Arnold Bake enough, which is why he did not only stop at filming them (the film can be seen here), but also asked Kusum to sing to his phonograph, accompanied by the drummer. Now, it is not as though these details were all given in Bake’s notes, the audio recording had the name of Kusum, the bhumij woman, the film did not have a description with a name. But looking and listening, alone and with others (especially discussing with Amy Catlin Jairazbhoy in 2010 and then she in turn asked Carol Babiracki), it was possible for us to match the film to the audio recording. In 2011, when we first launched the Travelling Archive website, we uploaded the Bake Bengal films with permission from the Archives and research Centre for Ethnomusicology in Gurgaon. If you go to the Bake page on TTA’a Related Research section now, you will see how little we knew at the time. Ten years on, there is absolutely no doubt about the identity of the dancers and the singers or that Kusum was a nachni.

Map of all the places Kusum could have come from. Map by Purba Rudra

Who could Kusum have been? How come she was in Kenduli? Was she from Bankura or was that her temporary home at the time when Arnold Bake saw her in Kenduli? The man dancing with her, her rasik, who was he? Amy had sent me in 2010 a copy of a note her husband, ethnomusicologist and student of Arnold Bake, Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy and she had prepared on the Bengal videos of Bake for their own Bake Restudy. This note was based on Bake’s own notes.

Notes from Amy Catlin Jairazbhoy, 2010

A nachni might have had many homes in many places, leading ‘an exceptionally nomadic life’, as Carol Babiracki wrote in her essay on Sundari Devi. ‘Like courtesans the world over, nacnis make an art of frustrating efforts to “know” them. Their desire to conceal in order to mitigate their triple social stigma (women, born “low-caste,” now “out-caste”) is certainly understandable, but these women actually seem to artfully cultivate the discourse of mystery that constitutes their performance culture in Jharkhand.’ (Carol M Babiracki, ‘Between Life History and Performance: Sundari Devi and the Art of Allusion’ in Ethnomusicology 52, no. 1 (2008): pp. 1-30. Accessed June 26, 2021.)

Senior jhumur artiste from Joypur, Purulia, Amulya Kumar, in my home, 2019. Photo: Abhijit Mazumdar

I had shared the song and film of Kusum with Amulya Kumar to know what he made of the recordings. I have known Amulya Kaka (as we call him) since 2005, there have been countless meetings and recording sessions. Kaka had come to my home on 5 December 2016. We had the following conversation; it is hard to summarise the content, because it so comes out of Kaka’s place and his life—he was born around 1938 and has seen and learned much. He had to just listen to the song and began to tell me the names of places from where such songs come: Bundu, Bagmundi, Rahe, Patratu, Ranchi. Then when he saw the video, he nodded in approval and said, ah! That’s what I was saying. She will have a handkerchief and not cover her head, sometimes there will be tassels hanging from both sides.

Amulya Kumar responds to Kusum’s song and dance, December 2016.

This is a ‘Tamariya’ melody, from Bagmundi. You know how the language of Purulia is different from Kolkata? Like that in these places they speak and sing in a different way—Rahe, Bundu, Patratu. He says ‘Patrahatu’. I ask him about what people there do for a living; work in the fields and forests he says, or do business. I ask about the life of the nachni, her relationship with her partner (rasik), about her song, about how she becomes a nachni. Kaka knows so much and his language is so beautiful, full of words which have a topographical dimension to them, signifying place. He hums and sings a few lines as he talks. ‘Ashadh maasher dine/Torope chhatiya’. You hear the Manbhum region in his those words and the way he utters them. Bengal is leaving Bengal and becoming Bihar—the song holds that middle place. Kaka says, it is the song which pulls the nachni out of her home. The song of the rasik. She goes with him. Lives a marginal life, is never given equal place with the wife. Always ostracised. It is a life of pain and suffering, but love too. He tells me a story about how, many years ago, 50 or 52 perhaps, when his eldest daughter had just been born, there was a girl who heard him sing and wanted to come with him. He was on an election campaign with the local candidate. He had to sing and draw crowds. The girl climbed on the jeep and said she would go wherever he went. ‘Oh my god! The sky came down on me!’ the 78-year-old man said and laughed his typical laugh. ‘My mother used to say, don’t sing when you are working in the field.’

Beautiful stories. There is an intimacy between Kaka and me—over the years, he has become a kind of parent. So, I can lovingly order him around: now you sit here, now you sing. He smokes his bidi and tells me most of the words of Kusum’s song and says we have such songs too, but we don’t sing them this way. These are biraho songs, songs of separation and longing. How does your song go? He sings a bit and stops. I don’t sing such songs. Why? Because it hurts, is it? Yes. You remember things. Your own things.

Then, there was my conversation with Bishu.

Bishu in Joypur, Bhaddi, Purulia. 2005. Photo: Sudheer Palsane

Telephonic conversation with Biswanath Dasgupta (Bishu) , 18 and 27 January 2021.

Bishu grew up in Joypur Purulia. His father was a doctor. They are not local in the same way as Kaka is, they are outsiders, arrived in this place for professional reasons, the educated middle-class. But Bishu is local in his own way. He grew to love the language and culture of Purulia, he never thought of leaving. I guess he was in his late twenties when we met, will be 42-43 now. He has deep knowledge of the folk arts of the entire Purulia, Bankura, Jharkhand regions, places of Jhumur and Chhau (the masked dance). He has worked as a theatre activist and organised folk festivals for decades. He has been a kind of conduit between the metropolis and his region. Bishu had taken us to Amulya Kaka in 2005. For about a decade we had not been in touch. Then we connected again.

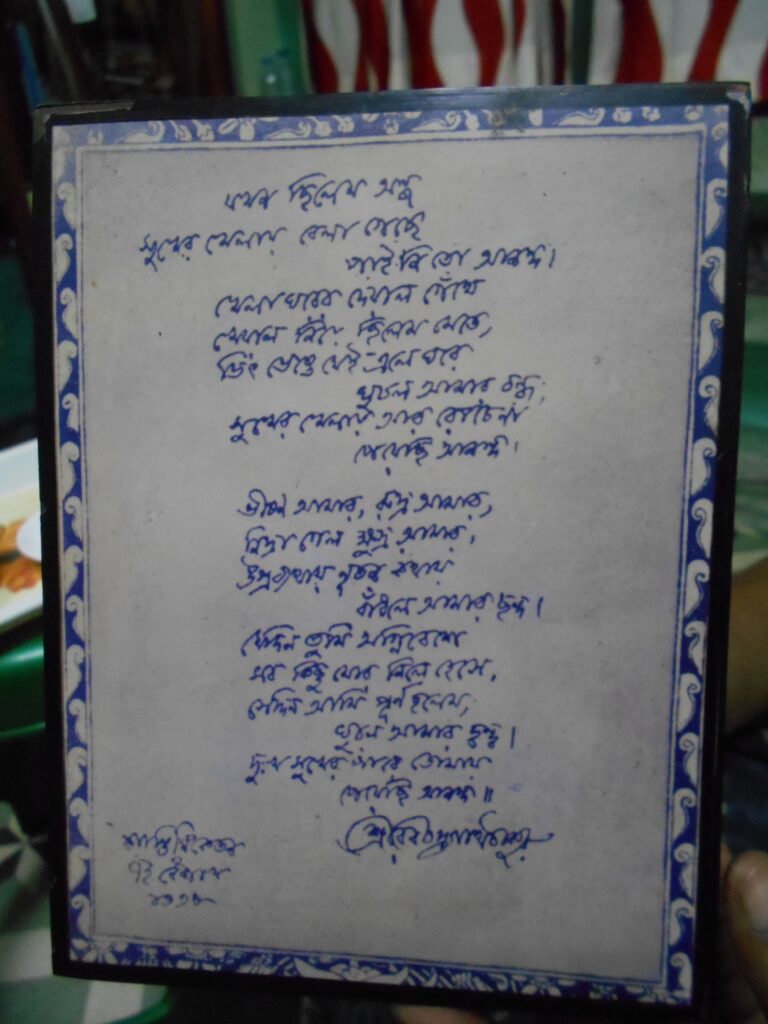

Bishu wrote this song in my notebook in Joypur, Bhaddi, Purulia in 2005.

Before I sent the file to Bishu we were talking about nachnis and why the women leave home. Bishu expresses himself in a way different from Amulya Kaka, he talked about sringar rasa—the essence of erotic love. He said they are often widows. The cry of the bhaduria jhumur pulls them out of their homes. He talked about Sindhubala, the renowned nachni who tried to bring recognition to their community and her artform. ‘She was 92 at the time and she said, you see Raja—she used to call me Raja [Bishu stresses on the ‘j’ and rolls the r, rrajjaa, he says]—she said, I am so immersed in this rasa that my life is slowly shrinking away. Rawshe thaikte thaikte shukhai gelam. And I said, how so? How can you be drowning in rasa and yet go dry? Even at ninety you are drinking, singing, and you say you are going dry? And she said, that is how it is. That is how it happens. It is this rasa which sucks the juices out of you.’ Then Bishu also talked about Kamala Jharia, the famous kirtan singer who had started life as a nachni.

Sindhubala Debi. Source: Internet.

When we talked again, Bishu had listened to the song and seen the film. He said, it is a treat to be able to see this. She is singing in Kurmali and dancing an ‘ekoira’ dance, meaning doing a solo performance. He talked about the evolution of nachni dance, those who sang and danced for the royal court, whose who performed for the ordinary people, then how the protocols of stage performance evolved. We also talked about the last time we met, the song he had taught me and I sang some lines.

Bishu sang ‘Kahan malin baje’ in 2005 in Amulya Kaka’s house, which I had learned from him. Recorded by Sukanta Majumdar.

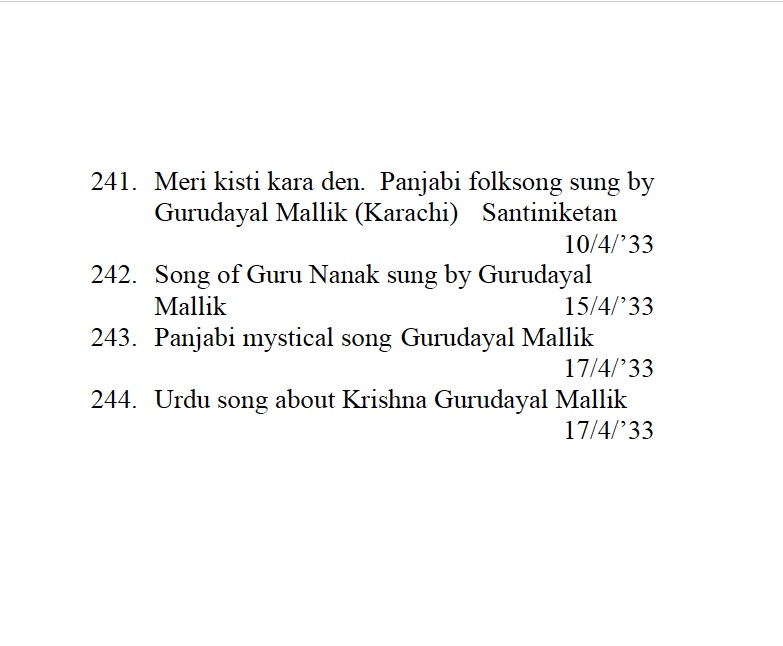

Gurudayal Malik (1896-1970), from Karachi, taught English to school students in Visva Bharati. Between 10-17 April 1933, Arnold Bake recorded him in the asram; he sang four mystical songs in Punjabi and Urdu on Bake India II cylinders 241-44.

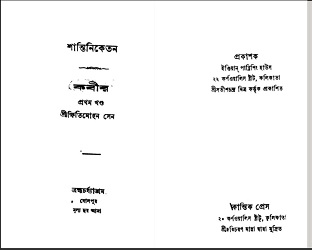

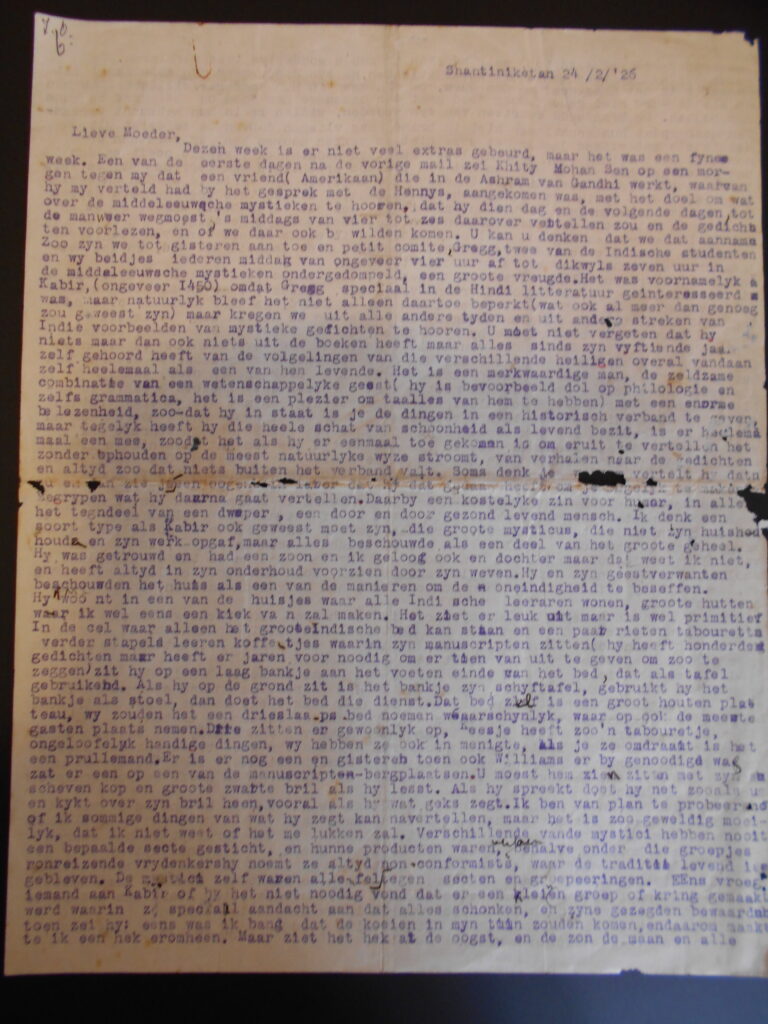

During the first phase of his Santiniketan stay between 1925-29, the medieval saints of India were a major subject of discussion between Arnold Bake and Kshitimohan Sen.

From left to right: Pages from Kshitimohan Sen’s anthology of Kabir’s songs, published in 1910; Kshitimohan’s book on the medieval poets, translated by Manmohan Ghosh; finally, Rabindranath’s translation of Kabir, with Everlyn Underhill, based on Kshitimohan’s anthology, first published in 1915.

They would go for walks together, besides having more formal lessons, and talk. Bake would attend Kshitimohan’s lectures. Bake was learning so much about the mystical poets and medieval saints of India from ‘Kshiti’, as he wrote in his letters home. For example, in his letter of 24 February 1926, he wrote page after page about Kabir, Dadu, Ramananda, Ravidas, Jnanadas and so on. Bengali author Pramathanath Bishi, one of the first students to join the Santiniketan asram as a boy, had written about how students used to be quite scared of Kshitimohan, mainly because of his sombre presence. ‘Yet it will be difficult to find someone who has not benefitted from his teaching,’ he wrote. ‘He would draw the student into the maze of difficult and dry topics and would light up the way of learning by striking the magic stone.’ Arnold Bake, we must remember, was not Kshitimohan’s student in the sense the asram boys were. He was a mature learner who had come from a distant land, who was also becoming a friend. There are some beautiful family photos of the Sens and the Bakes; Kshitimohan’s daughters would have been about the same age as the Bakes.

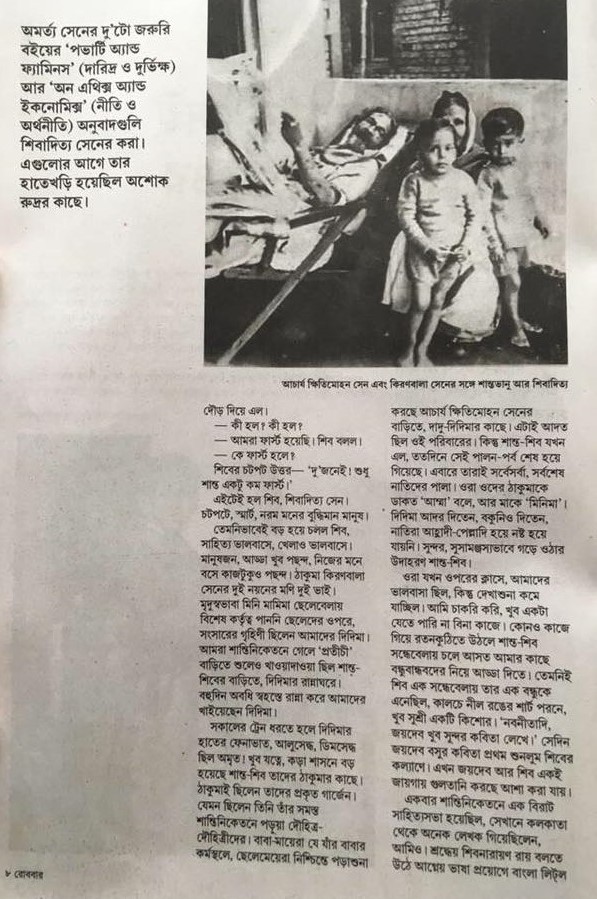

The Bakes with Kshitimohan Sen’s family, possibly taken in the late 1930s. Photo courtesy: Shibaditya Sen, my departed teacher and grandson of Kshitimohan. Shibda had dated the photo by seeing his older cousin, Amartya (later to become the famous Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen), third from the left in the front row. Amartya Sen was born in 1933 and the boy in the photo will be about five or six–that was Shibda’s calculation.

On 28 December 1926, Tuesday, Arnold Bake had written to his mother that the previous Friday, at about two in the afternoon, they had heard beautiful songs coming from the school of music. ‘This doesn’t happen very often, so we raced to see who it was. It turned out to be Mallik [it is interesting that Arnold Bake wrote Mallik, the Bengali surname, for Malik; the catalogue too has Gurudayal’s name as Mallik], a singer with a strong mystic disposition (maybe we already wrote about him last year, his farewell party was held just a few days after we arrived. He left to help is father, who is a very wealthy merchant in Karachi). Mallikji knows volumes of mystical songs, and he sings them with a rare beauty. His voice is a hundred times better than what is ordinarily found; but even without it, it would still be more than worthwhile to hear him sing, because he pours his soul into it. It is exceptionally touching. He was here only for a few days, but his dream is to come back and work under Gurudev, when his father will grant him leave.’ (Translated from the Dutch by Jan-Sijmen Zwarts)

From Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv’s list of Bake cylinders.

Arnold Bake’s relationship with Gurudayal Malik’s song, which began in 1926, continued through 1933 right up to 1950. Bake kept a record of the impression Malikji’s songs made on him in his letters; he recorded him with his machine; even archived his songs in his own body. In a lecture Bake gave in The Netherlands in 1950, talking about Indian folk and classical music, he sang one of the songs that Gurudayal Malik had sung for him on 17 April 1933, ‘Meherban meherban, sahib meherban’.

I shared the recordings of Gurudayal Mallik with Punjabi Sufi singer, Madangopal Singh to learn his thoughts and he sent me texts of the songs with some explanation (the above note is from one of his emails to me written on 3 November 2020). The song ‘Meherban meherban’, which Bake used to also sing, and which is mentioned as a composition of Guru Nanak in the catalogue notes, is in fact a composition of the fifth Sikh guru, Guru Arjan. Madanji wrote: ‘The entire text [as you can see above] is given here in Devnagri script with English translation as approved by the Sikh body, SGPC, whose knowledge of the English language is suspect in the best of circumstances. Two things could be special interest to you: a) The ‘shabda’ – hymn – is unambiguously attributed to the fifth Sikh Guru, Guru Arjan. Guru Nanak was the first Sikh Guru. He was followed in the line by Guru Angad, Guru Amardas and Guru Ramdas. Guru Arjan happened to be Guru Ramdas’s son and was martyred on the banks of the river Raavi in Lahore in the 16th century by a repressive state. b) Since the last stanza mentions the name Nanak, it may give rise to the suspicion that the author of the ‘shabda’ is Guru Nanak himself. That, in fact, is settled right in the beginning where the Mehla 5 is mentioned, that clearly identifies the fifth Guru as the author. It may be further mentioned that after Guru Nanak, no other Guru used his own name in any of the ‘shabdas’ he wrote. The name of Guru Nanak is used throughout from the second to the ninth Guru. That has been the practice.

‘A minor point finally: the recommended Raga is Tilang but it is by no means mandatory to sing in that Raga.

‘Of course, there are some textual deviations in the audio files sent by you and I can tell you that had the Sikh clergy got wind of that in the thirties, there would have been a minor storm in the poetic teacup of Mr Malik.’

Madanji also wrote about another song from that list. ‘The other song as I mentioned is a Prabhat Pheri (literally, the Early Morning Musical Walk of the mendicants) bhajan with a cleverly concealed message for the people to rise against the British regime.’ I kept pleading to Madanji to send me a song in response to what I had sent him. He said, ‘Much as I wouldn’t want to say “no” to any of your requests, yet despite trying over and over again, I have not been able motivate myself to either respond to the voice or the melody you had sent from your archive. I will most reluctantly have to say ‘no’. With warm regards from a diehard fan of your singing, scholarship and research, Madan’. I kept at it, though, and then Madanji sent me this absolutely beautiful song of Kabir, with his own translation.

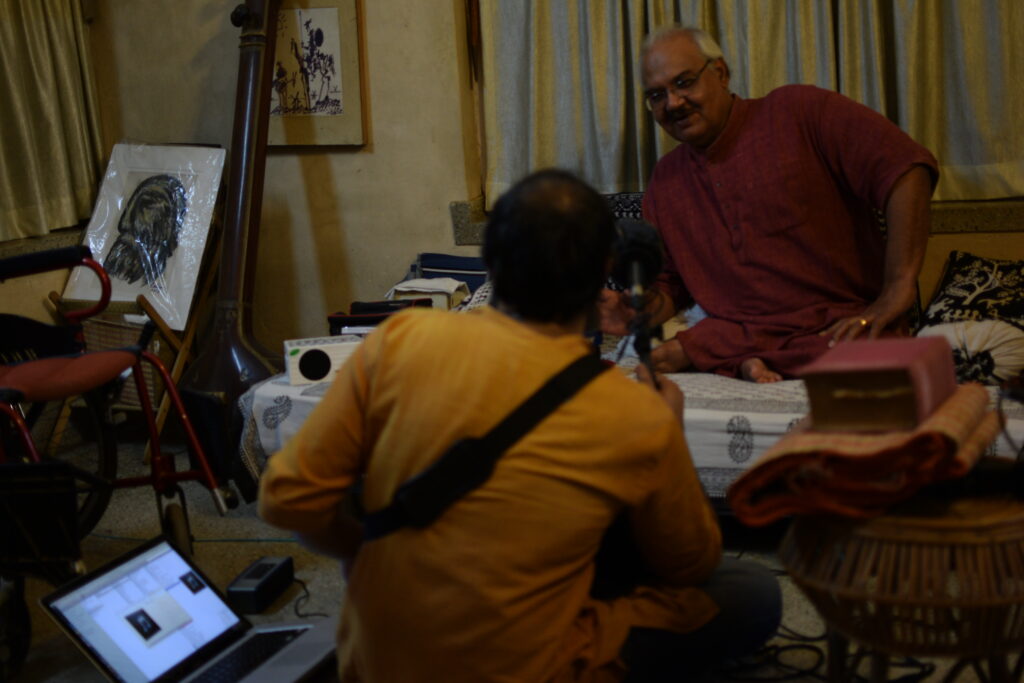

In 2016, while preparing for The Travelling Archive’s exhibition in Santiniketan, Time upon Time: Arnold Bake in Bengal, we had gone to meet the famous Tagore singer and retired professor of Sangit Bhavan, Visva-Bharati, Mohan Singh Khangura in his home.

Mohan Singh Khangura being recorded in his home in Santiniketan by Sukanta Majumdar. 11 March 2016. Photo by Jan-Sijmen Zwarts.

The choice of Mohan Singh was obvious; as there was a sonic continuity from Gurudayal’s voice to his, also a geographical contiguity, as both had journeyed from Punjab to Santiniketan, even if many years apart. In 1938, singer Rajeswari Datta (then Vasudev, later married the poet Sudhindranath Datta) had also come from Lahore to Santiniketan and studied in Sangit Bhavan for four years. Again, a journey from Punjab to Bengal, pulled by the songs of Tagore. I wonder why Bake never mentioned Rajeswari, or maybe he did and I am not aware of it, since she was one of the finest singers of Rabindrasangit we have ever had and they were contemporaries too. Both of them were part of the Tagore centenary celebration in London in 1961. Incidentally, Rajeswari also taught Indian music at SOAS, but that would be after Bake.

We can listen to a Rabindrasangit of Rajeswari Datta ‘Kichhui to holo na’ here

Anyway, coming back to Mohan Singh, or Mohanda, he sang some examples of Punjabi kirtan or ‘Asa di var’, and then he sang a ‘shabda’, and a song of Bulleh Shah and one of Kabir. These are absolutely precious recordings; they were made by Sukanta Majumdar in the presence of Mohanda’s older son Abir and the Director of the Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology, Gurgaon, Dr Shubha Chaudhuri. The date of the recording was 11 March 2016. I cannot remember the name of the tabla player.

A test recording, as Mohanda wanted to make sure the sound was alright

Mohan Singh sings a Punjabi ‘shabda’ or devotional song as is sung in gurdwaras

Mohanda sings a song of the 17th century Sufi poet of Punjab, Bulleh Shah. Then he says, no one to learn such things here, none to listen even. But I sing for myself.

Mohan Singh sings ‘Awal Allah noor upaya’, a song of Kabir

The celebration of the plurality of faiths and engagement with the Bhakti and Sufi saints and poets has been part of the culture of Santiniketan from its inception. It found its fullest expression in Binode Behari Mukherjee’s ‘Medieval Saints’ mural, which adorns the walls of the university’s Hindi Bhavan. The work was completed in 1947.

Source: Chakrabarti, Jayanta, R. Siva Kumar and Arun K. Nag eds., The Santiniketan Murals (Kolkata: Seagull Books, in association with Visva-Bharati, 1995). I thank artist Syed Taufik Riaz for lending me his copy of this book.

Slowly the sessions are moving towards listening to listening, layering recording upon recording. Now the tapestry has started to form. Seema Acharya is a renowned singer of kirtan and we went to her home in south Kolkata; we meaning sound recordist Sukanta Majumdar, I and Jan-Sijmen Zwarts, who has come from Utrecht to stay with me and help me read Arnold Bake’s letters. He took all the photos of the day. There were many with all the sweets and goodies we were treated to, which J-S’s lens especially saw, which I am not including here, although story goes that the older Dutchman whose footsteps he was following was also attracted to Bengali food.

On 8 February 2016, I took the recordings Olly had sent from London, singing Arnold Bake’s notation of kirtan to Seemadi, to see what she made of them.

A vibrant personality and of course a very fine and equally knowledgeable singer, Seema Acharya enriched us with songs and stories. She broke into song as she heard Olly play and sing, filling in with details about kirtan, endorsing Arnold Bake’s notation; thus endorsing Bake’s listening and interpretation. Our recordings of the day were made by Sukanta Majumdar.

Seemadi knows these melodies, she recognises them as being of the style of kirtan she has been trained in.

After the Nam Sankirtan played in Rag Pilu and Sindhu Bhairav, we come to ‘Esho duti bhai Gouro Nitai’ and before we can even start Olly’s song, Seema Acharya starts to play the harmonium and sing. She explains that this is the ‘adhibash kirtan’, a song about friendship and love, and without these true devotees, Gour and Nitai, no celebration of the divinity of Krishna and Radha is ever complete. When Olly’s song starts, Seemadi is amazed that what he is singing is so similar to her song. We come from the same school after all, she says. What she means is, Bake was taught by Navadvip Brojobashi and her guru Chhabi Bandopadhyay was also taught by him.

Here is a Brojobashi recording of Arnold Bake, which we got from the Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology (ARCE) in Gurgaon. First, ARCE’s archivist then, poet and sonic archaeologist, Uma Shankar Manthravadi makes an announcement for the recordings he sent for our website in 2010.

The comes Navadvip Brojobashi’s kirtan, recorded in Calcutta by Arnold Bake on 5 January 1932. Another recording can be heard on our Related Research page on Arnold Bake.

Seemadi talked about the far-reaching impact of kirtan, how it can touch so many hearts at the same time.

There is a short piece in Rag Behag and it sounds so Tagorean.

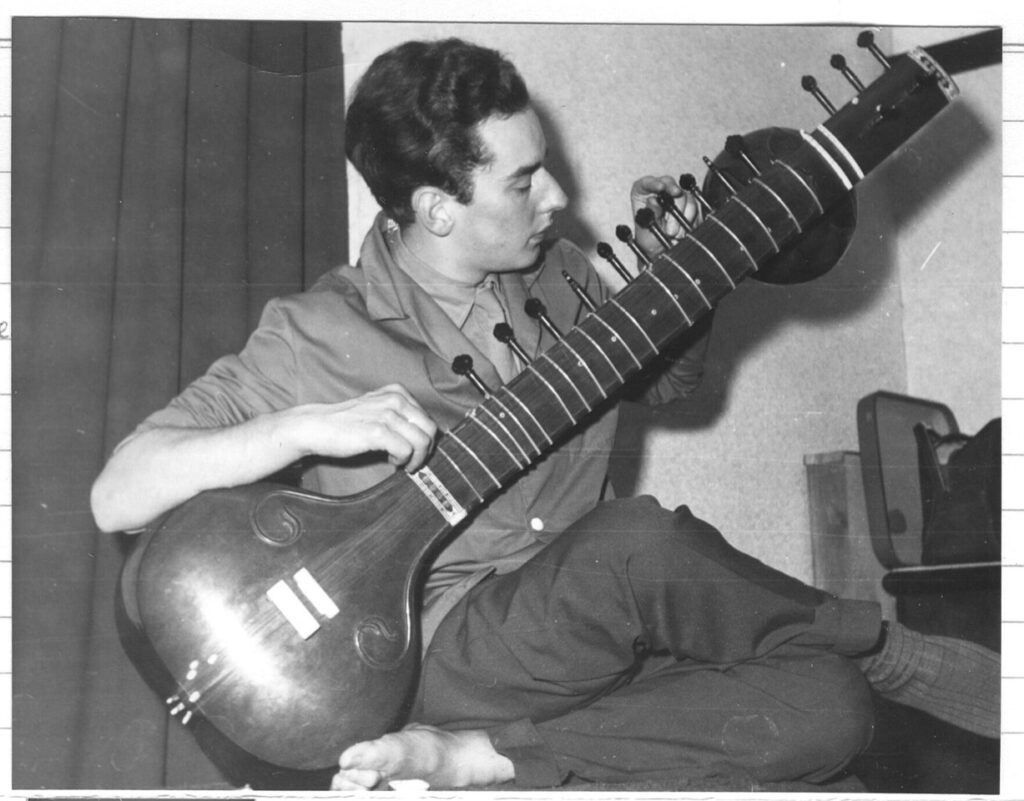

Seema Acharya talks about her family—her mother who sang, her father, Phani Bhushan Bhattacharya, who was from Mymensingh, from the bottom the Garo Hills, who was a natural musician and could play many, mainly string instruments.

Seemadi then sings the Mathur—songs of separation, longing and love.

She then talks about growing in a family of musicians, playing the guitar, forming a band called Green Leaves Orchestra, also singing English numbers such as the Jamaica Farewell! Then one day she listens to Chhabi Bandopadhyay and her life begins to change forever.

The shrine in Seema Acharya’s home, with her gods and her guru and a framed newspaper article about her.

Oliver Weeks is a British composer and multi-instrumentalist with whom I have been collaborating since 2002. We had a band called Parapar, between Kolkata and London, and even now we continue to make music together. I have learned so much from Olly and consult him on various—mainly Western classical music related—issues.

This is an old image, of Olly and me performing at Leeds University in 2010. Our other band members were also present, but I wanted to use an image of Olly at the piano.

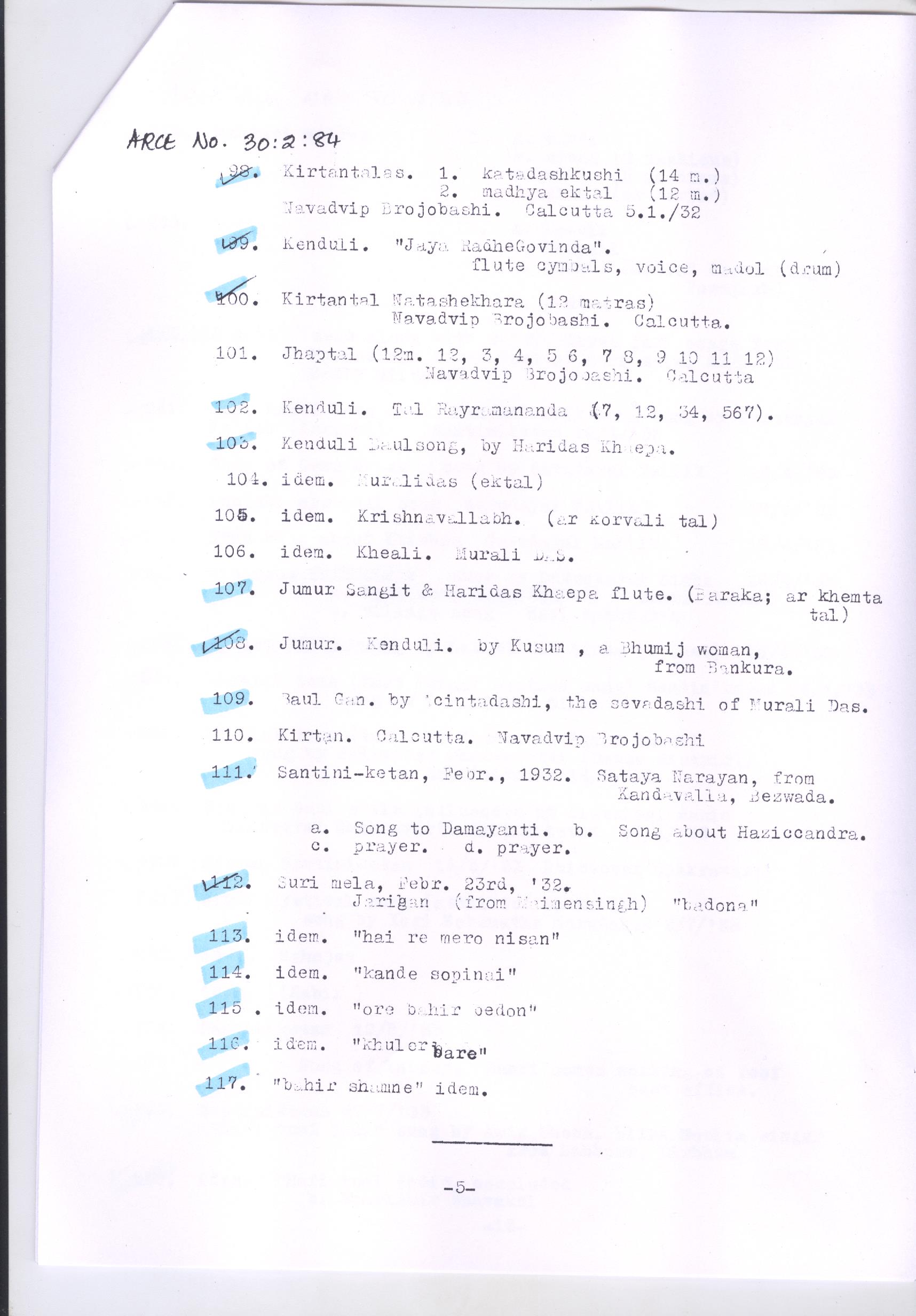

In 2015, I had worked at the Arnold Bake archives at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and found in his files some handwritten notation of kirtan from the 1940s, when Bake was taking lessons from his teacher in Calcutta (I write Calcutta, not Kolkata, as that is how the city was called at the time), Navadvip Brojobashi (1863-1951). (I am using the spelling on Bake’s list of wax cylinders at both the British Library and Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, although the name is spelt Nabadwip Brajabashi by historian Bob van der Linden in his biography of Arnold Bake and Nabadwipchandra Brajabashi by the scholar of kirtan Eben Graves. Earlier, in 1932, Bake had recorded Brojobashi on his wax cylinders (nos. 98-101, 110)—that is when they might have first met. As Bob van der Linden writes, ‘Arnold notated some kirtan songs as sung by the guru of Shashanka Chatterji, his Bengali teacher. He had met the guru before in Calcutta but only knew him as Sadhu Baba. From him, he learned nam kirtan or the singing of the holy name, a far more popular but unsophisticated singing style than that of lila kirtan, which he learned from Brajabashi. It is to lila kirtan, Arnold wrote, that “Bengal owes the best of her lyrical poems’ and it continued to be ‘an outlet to arefined and intricate, but most certainly very deep, religious feeling, not equalledin any other part of India”’, quoting Bake’s 1948 essay ‘Cri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu’. It is these notations which are kept at SOAS. I took photographs of the pages and gave them to Olly to find out what he made of them. Archival rules restrict me from putting my photographs of Bake’s papers in a public domain and in any case here I am trying to do something else.

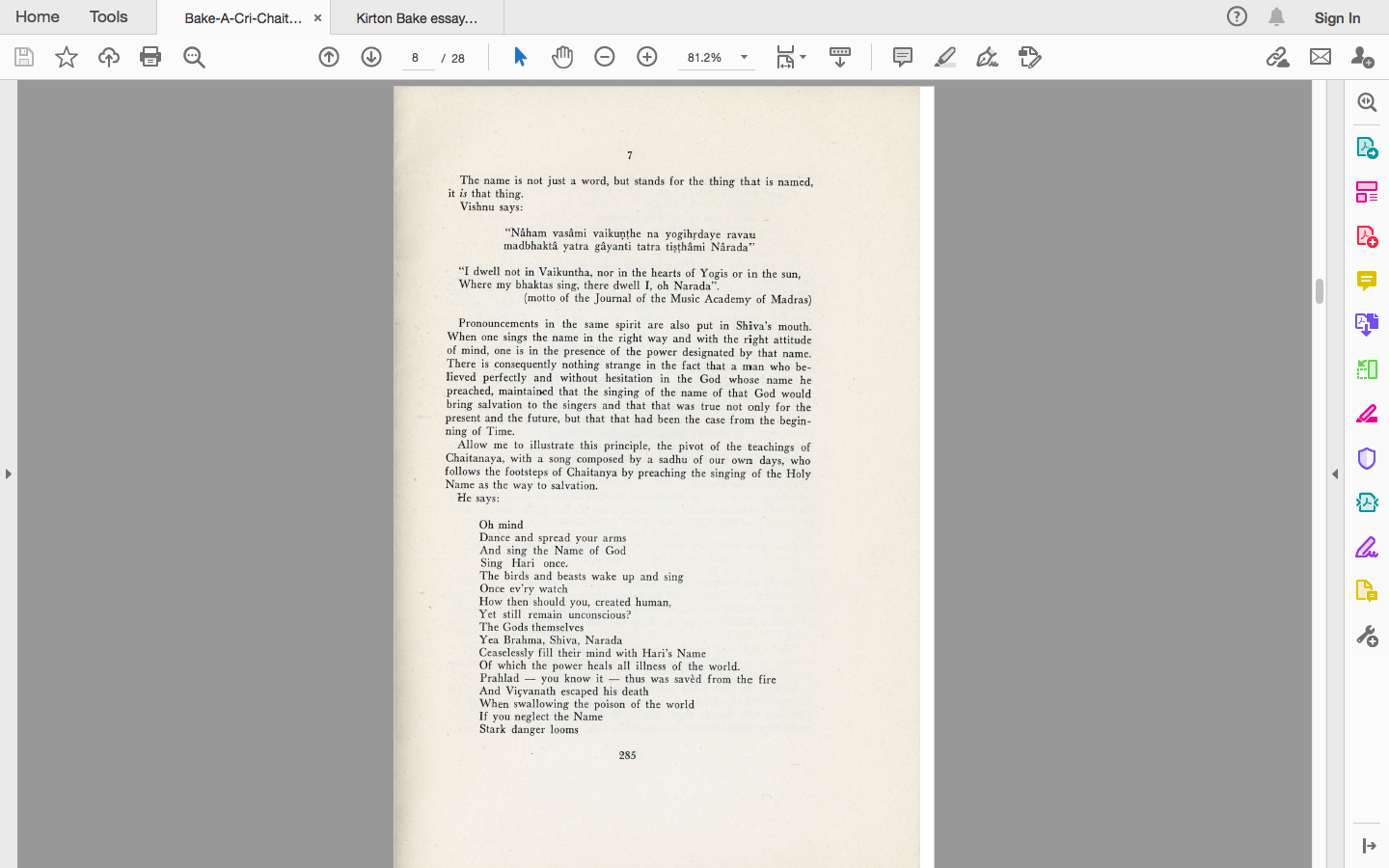

In the published version of ‘Cri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu’ Bake he did present some of the notation and here are two pages from that essay.

The notation that Bake made was a translation of sound into sign, and here the sign is being sung again, transformed back to sound. Between all these listenings and interpretations, so much has happened. To me, for example, if I were to listen to Olly playing the nam kirtan notation in Sindhu Bhairavi, I would never think of kirtan. Rather they bring to my mind Tagore’s melodies.

Arnold Bake had sung kirtan for two hours at Vrindavan in 1945, supported by his teacher Brojobashi on the khol. Bob van der Linden writes about how he sang five to six songs, sitting ‘in a cross-legged position among the musicians in front of an audience of a few hundred Indians. He did not feel very secure and was especially scared that he would not be able to join in on time after the rest of the group had finished their reply to his verse. Even so, he thought that he made few mistakes because Brojobashi’s drumming had led him through it all. Two years later, he wrote to the former American Consul in Calcutta, Edward M. Groth, that the performance was ‘one of the most cherished memories’ of his life.’ Linden, Bob van der, Arnold Bake: A Life with South Asian Music. (London, New York: Routledge, 2019), p.83.

I wonder how Bake’s kirtan might have sounded. I have heard his recordings of Rabindrasangit on Pathe, made in 1930 and for his lecture-demonstrations in the 1950s, he has sung both Tagore and other songs that he learned during his days in Santiniketan. The familiarity with the language and the music is evident in the renditions; I hear both a closeness and a distance, an insider-outsider voice in those songs. Olly too has been working with Bengali music for many years and he too has an insider-outsider location in this music, although this material is far more unfamiliar to him than it was to Bake. The announcements of numbers that he makes at the start of the recording are the file numbers for my photos of the notations from the SOAS archives. Olly made these recordings at his home in London and sent to me.

On our first trip to Naogaon, there was a man in our train compartment with whom we had got talking. He was a Bangladesh Railways staff who worked in the signals section at Ishwardi station, but he was on leave that day. His name was Mohammad Enamul Kalam and he told us stories about how he also practiced acupressure and healing and was returning from a patient’s house. He talked about many mystical things and I somehow felt there was more to this encounter, it would not end with this one conversation. So I asked for his phone number. Before this second trip Enamul bhai and I spoke on the telephone and we arranged to meet at Ishwardi station. I was anyway fascinated by the idea of a man who signals trains to halt and pass. Also, the name of these stations.

After last year’s trip and the visit to the Naogaon Ganja Society Cooperative office, I had a feeling that I would now have to look elsewhere for the fakirs on Bake’s cylinders and maybe I would be able to come back to Naogaon at some later stage. The folk music collector Muhammad Mansooruddin (1904-87) – this is the spelling he might have liked to use, with a double o, as I have seen his letter to Arnold Bake signed thus, although the conventional spelling is Mansuruddin—was Arnold Bake’s companion on his 1932 Naogaon trip. He came and met the Bakes at Santahar station, then took them in a carriage to Naogaon where they would be staying with the Sub-Divisional Officer, Annada Shankar Ray, himself a reputed poet and essayist, and his American wife Lila, also a writer. Mansooruddin was with Bake when he was making his recordings on 28 February 1932. He was making his own recordings, albeit in his notebook, as has been recorded by Annada Shankar in an essay. My thoughts were that perhaps the songs Bake recorded later appeared in some volume of Mansooruddin’s Haramoni?

I was accompanied on this trip by Dhaka-based filmmaker-photographer Moti Rahaman, a nephew of Mansooruddin’s, and his wife Nowrin Oshin, a young writer and editor of a journal on environment. Moti had been trying to work on Mansooruddin, but the rest of the family weren’t so keen to build an archive with the papers and correspondence of this man’s amazing collection of folk songs, published in 13 volumes, between Calcutta and Dhaka. Much of the material must be either lost or scattered beyond retrieval. I thought we could look for the songs Bake recorded in Mansooruddin’s volumes, itself a difficult task. Before that we would have to be able to listen to the songs, get a sense of the words and thus know what to look for. All of this would take time. Going to Mansooruddin’s home, seeing his grave, going to the station where he had met Bake, tracing the route the Bakes would have taken—that would give a sense of a lost time, I thought. Moti, Oshin and I took a bus from Dhaka to Sirajganj.

From these recordings, the listener will get a sense of place and time. As I am listening again, I can listen to my mind, formulating the questions. I am moving bit by bit, looking, listening, feeling, searching and finding too.

We had to wait for a long time at Ishwardi Road station and Enamulbhai told us stories about trains and stations. Oshin and Moti joined in, Enamulbhai read Oshin’s palm and told her, her story!

Then on the train to Santahar, Enamulbai and I chatted with a man from Joypurhat about the land and crops and catching fish in Chalan Beel—the estuaries which form when water from the hills flow down and flood the fields, transforming them into lakes. Then the villages become little islands and people go from place to place in boats. I asked the man if they grow ganja in Joypurhat and he said no. Then Enamulbhai told us a story about tasting ganja for the first and only time in a friend’s house near Akkelpur, near Naogaon.

At Santahar station I wanted to get a feel of what the place must have been like when Bake came here all those years ago. We went for a walk and Enamulbhai talked about the railways and old stations, Jagatee and Pakshey and the Hardinge Bridge, built in 1915.

These photographs by Sarker Protick capture for me something of that old time of what we were talking, although they were taken some time in 2018-19.

We took a real roundabout route to Pabna that evening, first going by bus to Bogura and another bus to Pabna. We would stay with Moti’s cousin Shariful Islam Bablu that night. Then the next morning folklorist Uday Shanker Biswas came to meet us from Rajshahi; we had met on our first Naogaon trip. We all set off for Sujanagar, Mansooruddin’s home, where Moti’s cousin Babul Mandal lives now. The women of the house had cooked a huge meal for us while Babulbhai told us stories about the Padma river.

And we went to see Mansuruddin’s grave.

From here Uday, Moti, Oshin and I went to look for a place in Sirajganj by the name of Bordul, which was in Pabna once, and which might have been my father’s village, but found ourselves amidst green fields and broken tracks. I could not find any trace of my father’s village, but tried instead to listen to the way people talked. Had my father stayed on here, would he too have talked this way?

There was Arnold Bake’s footage of kirtan that we had taken to show to the kirtaniyas of Mainadal in 2014 and the then oldest singer of the Mitra Thakur family, Sri Manikchand Mitra Thakur (died 2018), had said that perhaps the singers in Bake’s film were from Muluk village (not far from Bolpur-Sriniketan). Musicians are seen playing multiple instruments including the shinga (the S-shaped horn) and shanai (shehnai), and a violin and khol (clay drum played with the hands) and dhak (played with sticks), and it looks like a veritable orchestra. There are singers too.

The Arnold Bake archive catalogue of the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv gives the following details for Cylinders 76-79:

76. Mongoldihi, Nov., 1931.

Kirtan (tal Lopa.) Rag jhingit

77. idem. One Shannai, tal lopa, rag jhinjit

78. Kirtan idem.

79. idem. Instrumantel. 3 shannai, one khol, one cymbal

Could this film be from Mongoldihi? Could these songs be from the same place, recorded on the same day?

When we launched this website in 2011, we had this film from ARCE , we did not have enough knowledge to judge the opening lines: ‘Kirtan music in honour of God Krishna by low caste villagers’. Yet, these instruments did not seem to corroborate with our own limited the idea of the sound of kirtan. Hence, we superimposed our own judgment on the footage: ‘…this does not look like kirtan. Even Bake’s own recording of kirtan does not match the instruments shown here.’ I am not erasing that subtitle now, in 2021, as it shows something of my way of working–going to the same place and same song and same archival recording over and over, because that is the only way for me to learn and correct past errors. I have uploaded the film here again, this time the version I had from Amy Catlin-Jairazbhoy, with Bake’s opening statement inverted.

The reason I could not see this footage as Mongoldihi’s is because I had not heard the Mongoldihi recordings, even till the time of my visit to Mongoldihi. What I had from ARCE for cylinders 76-79, and what I also have from the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv are recordings from Nepal (I think) instead of the kirtan and so some mix-up has happened somewhere along the line. The British Library opened their listening platform after 2016, perhaps in 2017, and now the actual Mongoldihi recordings can be heard here. Click on 11/31 and you will find a range of sounds—the shinga and the Santal flute and kirtan—and you can feel the presence of the many people who were part of Arnold Bake’s field that day on 26 November 1931. Not just the people we see in the film, but others too. About this day he later wrote to his mother: ‘We were too tired to go out in the evening. The next morning started with a performance before the magistrate; first by school children, then all kinds of musicians, singers and instrumentalists, with whom I was occupied until about one o’clock. I got six cylinders worth of material, if I’m not mistaken, and a bit of film too.’ So this indeed is that film that we are seeing.

In his letter of 26 November, he also wrote: ‘Wednesday evening was the great procession. The statues of Balarama and Krishna were carried out of the temple with music and song and taken to a little place …[which had been prepared for their landing]. There they were put down, and the conch was blown, while fireworks were lit to celebrate and honour the deities. Mr Datta [Gurusaday Datta, the then District Magistrate] could get very close, and we were allowed to get close all over, much closer than we have ever dared ourselves. There was a hell of a crowd on the way, but not as much as the other years, because this year the country has just been decimated by malaria. Mongoldihi was only at half strength, and just yesterday we heard that in Surul fifty people had died. [Here the poor] People have very little resistance.’ (Translated from the Dutch by Jan-Sijmen Zwarts). Bake was describing the Raash Utshob.

We heard stories about the tradition of Raash Utshob in Mongoldihi, the tradition of the music, the shinga players and where they came from, the Santal flute, and dance and what has become of the place now. I went to Mongoldihi on another 25 November, 84 years after Arnold Bake. I went with the painter Milan Mitra Thakur, whom we first met in Mainadal the previous year and who had by now become someone I could call anytime and ask for clarification and advice—a mentor of sorts. Also someone who was emerging as their own archivist (See how Milanda is taking a leading role in gathering recordings and other material related to the Mainadal Mitra Thakur family’s heritage). Many of the photographs of my Mongoldihi trip were taken by Milanda.

Sukumar Banerjee, Diptendranath Narayan Thakur, Samitendra Narayan Thakur and others talked about their Raash Utshob in Mongoldihi. They also talked about the spontaneous participation of the Santals in the festivities in the past, their flute sounds, and how some of that spontaneity is now lost, giving way to caution.

They talked about their house deity and showed the family tree. Milanda poured over this genealogy chart with Sukumar-babu. It reminded me of Mainadal and how they sing their ancestors’ names at the end of their Nandotsav festival.

Then we watched Bake’s film together.

Watching Bake’s film with the Mongoldihi family. Photo: Milan Mitra Thakur

The Mongoldihi people were excited to see the musicians and the musical instruments, but they were disappointed that none of their ancestors had been filmed.

Music and conversation with musicians Dhiren Das, Dhorai Das, Manik Das. Dhiren Das said his family had been playing at Mongoldihi’s Raash Utshob for generations.

Some faces bear shadows of the faces in Bake’s film

The conversations in Mongoldihi happened before the main festivities began. Then Milanda and I went roaming to see the mela.

Then the gods were taken out and crowds of people walked in a procession, much like Bake’s description in his letters.

It was in 2015, while researching for The Travelling Archive in East London exhibition that I came across two recordings of Arnold Bake from 1956 which were from Bengal—there were two more recordings from that trip, which I did not notice till 2018. To those I have dedicated another sub-chapter.

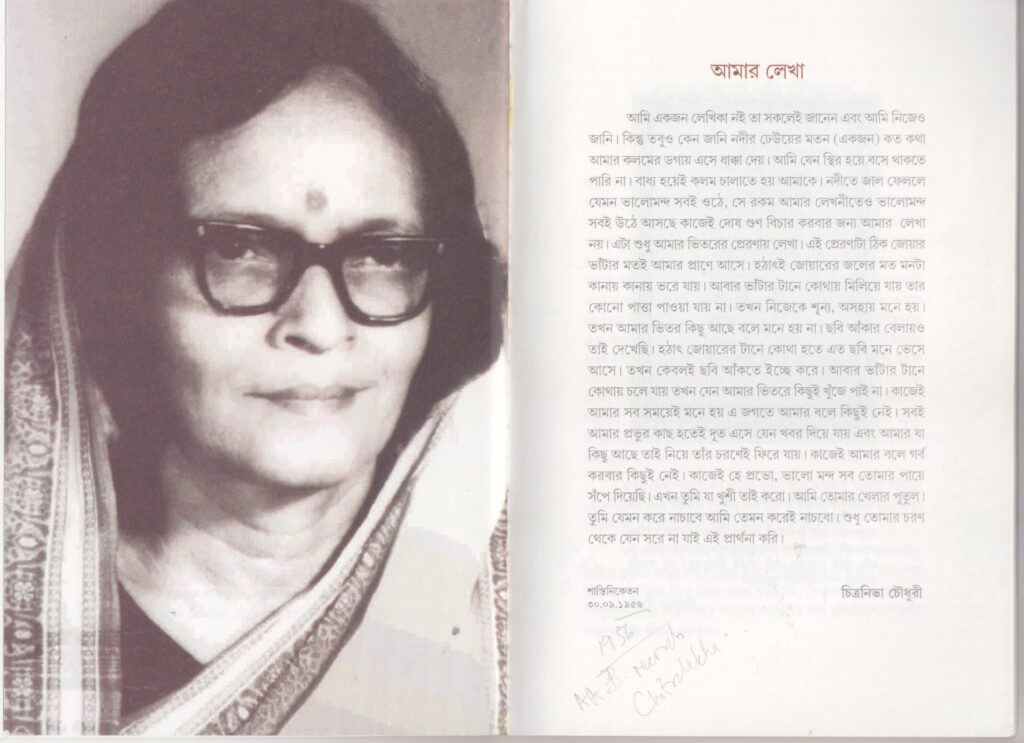

The artist’s name for item number C52/NEP/70 C1 was Chitra Chaudhury. According to the accompanying archival note, she recorded a Tagore song for Arnold Bake in Santiniketan on 7 March 1956. C52/NEP/71 C1 was marked as a Tagore song sung by Indira Devi Chaudhurani, recorded on 10 March 1956. The place of recording for Indira Debi was given as Nepal, but that was obviously an error; I assumed this would also be Santiniketan, because I knew that Bake was visiting old friends in Calcutta and Santiniketan at the time.

Chitralekha Chaudhury in her home in Sinthi, Kolkata on 16 November 2015.

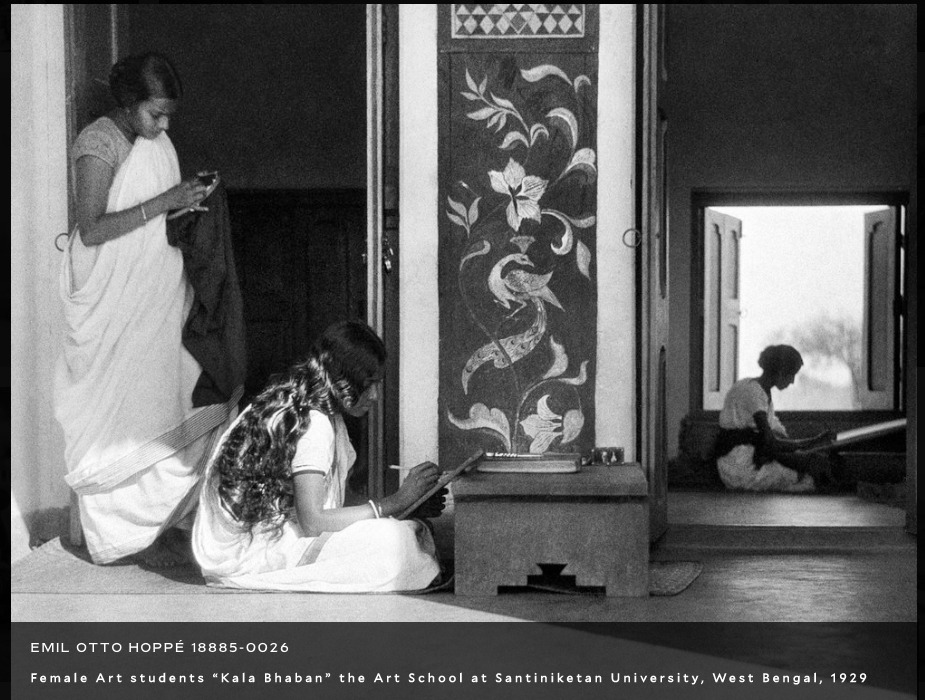

As with many of the other Bake recordings, it was the archival note which came to me before the sound; hence, speculation began from the text. Could Chitra Chaudhury be the renowned Tagore singer Chitralekha Chaudhury is the first thought which crossed my mind. When I listened to the recording, I felt I had probably guessed right. In the recording, the singer is young, so I had to make some more inquiries before I could be certain. After the exhibition in London in June-July 2015, I returned to Kolkata and sought out Chitralekha Chaudhury. She was my old friend, also a singer, Nabanita Chattopadhyay alias Tuku’s teacher, so I asked her to find out if her guru remembered ever being recorded by Arnold Bake. Tuku said Chitralekhadi was keen to meet me and so sound recordist Sukanta Majumdar and I went to her home on 16 November 2015. The recordings of that evening in Chitralekha Chaudhury’s home were all made by Sukanta, the photos were taken by either of us. Chitralekha’s daughter Patralekha Reena was also present and we all listened together to the 1956 recordings of Arnold Bake and other recordings too. The recordings were keys to long-unopened vaults of memory. Chitralekha was listening to herself and remembering the day of the recording, her painter mother, Chitranibha, life in Santiniketan, old teachers and so much more. Those days people mostly called her Chitra; in 1956 she was a student of the secondary school of Visva Bharati, Patha Bhavan. Her mother, the painter Chitranibha Chaudhury, was among the early women graduates of Kala Bhavan, who also taught there later. ‘She was the first lady professor of Kala Bhavan,’ her daughter said with great pride.

Chitralekha Chaudhury listens to her song, ‘Amala dhabala paale legechhe’, and she begins by talking about how this was the song she would often sing in those days. Born in 1940, Chitralekha was fifteen going on sixteen at the time of the recording. She talks about early music lessons in Santiniketan from master teachers and how her mother made every effort to arrange for the best music education for her daughter. She sings a few lines of the song she had sung as a child for Allauddin Khan, ‘Jago jago’, when the master came as a visiting professor to Visva Bharati. She recalls the transcendental quality of his music and the depth of his sadhana and his total humility as a person. She especially mentions a performance one autumn evening where the master sat and played for over two hours, his white robe turning green as seasonal flies landed on him and bit him to their fill. The artiste was totally impervious to such mundane matters; after his performance the lord stood up and shook the flies away. Chitralekha also remembers the singer of the Bishnupur gharana, Gopeshwar Bandopadhyay’s visit and how he gave her individual lessons because she was too small to learn in a group and how he slowly prepared her to sing with him during performances. She recalls her ‘guru bon’, fellow student of Gopeshwar Bandopadhyay, the famous Hindustani classical singer Malavika Roy (later Kanan), already on her path to fame.

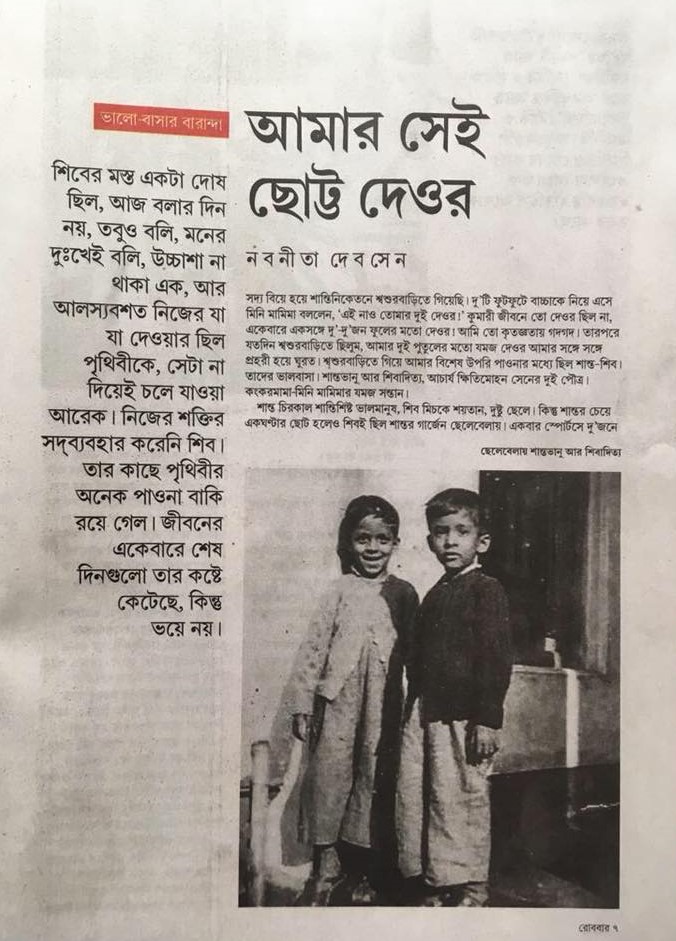

Allauddin Khan in Santiniketan, with the painter Nandalal Bose on his right and Tagore singer Sushil Kumar Bhanja on his left. Scanned from Robibar, the Sunday magazine of Sanbad Protidin, 2 March 2015 (Kolkata: Protidin Prakashani Limited, 2015), p.24.

Chitralekha tells us the story of how her mother was married, how Chitranibha’s in-laws recognised her potential as an artist, and how they believed that in the struggle against British rule, women would play a vital role, so they had to be prepared for it. That is how she came to Tagore’s school in Santiniketan to study at Kala Bhavan with Nandalal Bose and others. She also learned to sing from Dinendranath and Rabindranath himself.

This photograph is from E. O. Hoppe’s book, Santiniketan; it was on the cover of the book. The photo was taken in 1929 and it struck me that one of the unidentified women could be Chitranibha Chaudhury. As we hear in this telephonic conversation on 12 February 2022, Chitralekha, has identified the woman with flowing hair and shankhaa (conch shell bangles), sitting on the floor, as her mother. Image source: Internet.

Chitralekha continues to tell her mother’s story. How her mother had to regularly report to Rabindranath about her progress. She would go and show him her work. One day she took a design of a rectangular frame, with nothing inside. Rabindranath said, why this empty space? Maybe you should write a poem. She said, but I can’t write poems. He said, then leave it on my desk. The next day she went and found that Rabindranath had written a beautiful song about blindness and the awakening of sight to fit her frame.

Chitralekha talks about their family estate in Lamchor village in Noakhali, now in Bangladesh. This was a prominent zamindar or landowning family. On her father’s side of the family they were all scientists and educators, they had set up schools in the village, their house was like a boarding for students who were also trained in rifle shooting, because they would have to fight the British. Her father, Niranjan Chaudhury, was a member of the Anushilan Samiti. She said, later that training came to use during the communal riots of 1946. All around them there was killing, arson and looting, but their lives and property were saved. Chitralekha tells us how her mother went home to her in-laws after five years in Santiniketan and the house seemed like a hostel to her. Chitralekha also tells us how her mother’s original name was Nibhanoni but Rabindranath changed it to Chitranibha, because she was such a good painter. That is the name she came to be known by later.

Page from Chitranibha Chaudhury: Smritikatha (Kolkata: Rajya Charukala Parshad, 2015)

Chitralekha briefly mentions the fresco that her mother had painted in her uncle’s house in Dhaka. Chitranibha’s husband had studied mathematics and his elder brother, Chitralekha’s jethamoshai or uncle, Professor J. C. Chaudhury, was head of department of chemistry of Dhaka University. The fresco in question was painted in his house. This fresco and its disappearance have slowly come to hold metaphorical meanings for me in my research, symbolising history buried under history, but we will come to that later. For now, Chitralekha goes on to talk about the riots in Noakhali, about how Gandhi had stayed in their house after the communal riots of 1946. Her father, Niranjan Chaudhury’s room was where Gandhi had stayed, she says, her uncle’s room (I believe she meant her uncle Manoranjan Chaudhury, who was a friend of Gandhi’s) became his private secretary’s office (Chitralekha could not recall the name, but of course she meant Nirmal Kumar Bose). She says, the memory of the riots was too bloody, which is why she has never been able to go to Bangladesh.

As I was listening back to these recordings in 2021, I realised that there were some gaps in my understanding of the Lamchor Chaudhury household, of Chitralekha’s father Niranjan Chaudhury’s circumstances and so on. So I called Chitralekhadi and we spoke on the phone about things. It is interesting to think how memory works. She repeated some of the things she had said in 2016, such as her mother proposing to her father that maybe they could think about exchanging their Noakhali house with her friend Firoza Bari’s in Park Circus, Calcutta. Her father had apparently said, are you crazy? This is all temporary, Hindus and Muslims will come back together again. And then she told me again on the phone how her father really did not want to come and how Gandhi had said to them that you must not leave and how he finally said. ‘I can part with one of my limbs but I cannot part with my party.’ Whether or not this is historically accurate is not for me to say, but this is how Chitralekha knows and tells and retells her own history, the history of her family as well as the history of a nation.

Conversation with Chitralekha Chaudhury on the phone, 31 May and 1 June 2021.

This is again from 16 November 2015. Chitralekha Chaudhury tells us the story of how this elaborate fresco that her mother had painted in the house of her brother-in-law, Professor J. C. Chaudhury, in the late 1930s after she had graduated from Santiniketan, was finally ‘lost’.

When Partition was imminent, Professor Chaudhury exchanged his property in Dhaka with a family in Calcutta. Apparently, when leaving the house and the country, he had told the new occupants to look after Chitranibha’s fresco. ‘Murals are not just paintings or relief on the wall; they generate in the building or its surroundings a new kind of vitality. Their role, therefore, is organic, not ornamental,’ K. G. Subramanyan had said. There are many styles of mural painting; fresco is one of the toughest, as artist and scholar Professor Nisar Hossain, who has written on Chitranibha’s lost fresco, was explaining to me. The fresco of Chitranibha in Dhaka became shrouded in mystery after Partition—people talked about it; Chitralekha and her mother heard stories about it from visitors from Dhaka. Meanwhile, the house changed hands again. Parallel to these happenings, Nisar, who teaches at Charukala, the art school of Dhaka University, had set out on his own journey to find this bhittichtro or fresco, of which he had heard so much. The house was located on 12 Topkhana Road, Segunbagicha, Dhaka. He reached it through a circuitous route and the journey was not easy. The room with the fresco was found—it used to be a large hall, according to earlier descriptions, but now it had been partitioned and it was the office of a company which sold water pumps. The room with the painted wall was now a storage piled with boxes to the ceiling. The wall with the painting was found, but problem was that it had been whitewashed.

Caption: While the walls of the house with the mural have now been whitewashed, these faded photographs of the mural which lie behind the white wall have been shared with me by Nisar Hossain. Nisar had these from Abdul Hamid of Bitopi advertising agency, who were working once on a calendar project on Dhaka’s murals (I do not know if the calendar was printed. One panel bears the signature of Chitranibha and the date is 7 Chaitra 1349 (BS), which would be March 1943. However, Chitralekha insists the fresco was painted before she was born. Hence the assumption is that Chitranibha had signed the mural during a later visit to Dhaka.

There were traces of Chitranibha’s village scenes behind the coating of lime and blue; there were pencil-marks still visible on the wall. On 20 February 2016, I went with Nisar to the house where the largest fresco panel of Bengal had been painted around 1939, prior to Visva Bharati’s Hindi Bhavan mural, painted by Benodebehari Mukhopadhyay in 1946-47. Nisar showed me signs of the fresco, which his expert eyes could see. Everything hinted at a history now impossible to see, but a history that lies under the surface of the obvious and the visible.

What used to be Professor J. C. Chaudhury’s house. 2016. Photos: Jan-Sijmen Zwarts

Visiting 12 Topkhana Road, Segunbagicha, Dhaka with Nisar Hossain and others on 20 February 2016. Jan-Sijmen Zwarts, a young Dutch scholar, who was staying with me at the time and helping me read Arnold Bake’s letters, had also come to Bangladesh. I made this recording on my Zoom H4N recorder.

On 16 November 2015, Chitralekha Chaudhury had talked about her first album, a 78 rpm record. The Tagore songs on the two sides of the two sides of the album were ‘More bare bare phirale’ and ‘Ei je kalo matir basha’. She narrated her father’s initial objection, her mother’s encouragement, and finally how she was recording record after record and her songs were playing all the time on the radio, while she was studying for her Masters and then she started to teach in a college and went on to do her PhD and so on.

Chitralekha Chaudhury tells a funny story about how she ended up going for military training and how she carried her harmonium to the camp and so on.

Finally, we come to Arnold Bake’s recordings, we listen again, I explain to Reena that I cannot give her a copy of her mother’s songs but she records while we play. Interestingly, after I sent Chitralekha Chaudhury’s postal address to the British Library after our meeting in November 2015, they sent her a copy of her 1956 recording with a standard letter explaining what was being given to her and how she must keep it and how she must not make further copies. Rules are rules, but we have to also find our own ways of dealing with these systems. Reena, also a singer, wanted to keep a copy of Indira Devi’s song too, and how else could she do it other than by recording on her tablet while I played the song? Chitralekha talks about Bibidi (Indira Devi) and about learning songs from her. I ask her about some of the other people Bake had recorded in Santiniketan. She tells me what she remember. Laksmisvar Sinha used to talk about the land of endless sunrise and endless sunset. Gurudayal Malik was very sweet and kind and when my little brother touched his feet and did pranam to him, he touched my brother’s feet in return and said, god lives in the heart of the children. I also play them Arnold Bake’s own recordings of Tagore’s songs and ask her, if he is singing in Dinendranath’s style? He is and he is not, she says. He is also a Western trained singer, she clarifies..

Chitralekha is married, she has gone for post-doctoral research to Laval University in Quebec and thinks she should learn some Western classical music. She goes for voice training but realises that is not for her. So, she takes to learning the piano. Then her teacher, Marie, asks her one day about Tagore and asks her to sing one of his songs. Chitralekha plays the piano and closes her eyes and sings ‘Chokher jole laglo joar’. There is total silence. When she opens her eyes, Chitralekha sees tears streaming down her teacher’s cheeks. Here was someone who had never been anywhere outside her own world of sound and listening, yet here she was so deeply moved by a song.

‘Time Upon time: Arnold Bake in Bengal’ is an exhibition we had in 2016 in Nandan gallery, Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan. Our main guests that evening were Chitralekha Chaudhury, who had been recorded by Bake in 1956 and Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur, whose father and grandfather and uncles and cousins had been recorded in Mainadal, Birbhum in 1933.

Arnold Bake had recorded the fakirs in Naogaon on 28 February 1932. Naogaon was a subdivision of Rajshahi district till 1984 and is now a separate district in northern Bangladesh. Bake India II Cylinders 83-94 are from Naogaon; 83-87 are names of male fakirs, 88-91 are of a woman named Jaura Khatan Khaepi, a fakirni . The rest, 92-94 are of ‘ganja workmen’ Azimuddin, Saura Ali and Komaluddin Sardar. Again, these are recordings I have heard at the British Library and ARCE, but now we also have copies of three cylinders, as we have just come back from an exhibition in London where we had some Arnold Bake recordings from the British Library as exhibits.

The word fakir is also written as fokir, even phokir in its Bengali to English transliteration, to bring it phonetically closer to both the ‘o’ sound and the closed-lip pronunciation of the Bengali letter ফ. However, Fakir is how Arnold Bake wrote, hence that is the spelling I have used to write about his work. I am also using Bake’s spelling for the name of the fakirni, Jaura Khatan Khaepi. But the name would possibly be written as Johura Khatun Khepi even at that time. My hunch is that Bake tried to write a spelling closest to what he heard and in those parts, they probably say Jaura for Johura.

Anyway, fact is that I was especially drawn to Jaura Khatan and had been musing on her for several years. Way back in 2013, the essay I wrote for the ‘La Presencia del Sonido’ (The Presence of Sound) exhibition had included some thoughts on her. She was for me the main point of this journey. Who was Jaura Khatan, mistaken as male in the BLSA catalogue notes (‘Āmi nāmāj parete jāi calo re Khaepi, Jaura Khatan (singer, male / ektara), a lone woman in a group of men whose photograph I had seen at the Leiden University library and copied with my camera?

The other intriguing point was the epithet ‘ganja workmen’. It took me a long time to work out what this meant, and that the ganja workmen were indeed people who worked in the ganja (cannabis) fields of Naogaon and that ganja was one of the main produces of the region, and what kept its economy and culture alive. By the time of this first trip to Naogaon, I had gathered some information about the cultivation of ganja in the region, but it was only after actually going there that I began to get a proper sense of the scale of its ganja operations at the time of Bake’s visit.

On this trip no one recognised the photos but the relation of the fakirs with ganja became evident. Ganja was banned in Bangladesh in the 1980s, the office of the Ganja Cooperative Society still stood in Naogaon, and its workmen managed old property and land now turned into markets and fisheries.

The fakirs used to come when ganja was grown, they said.

There was not that much sound to record, but more images and impressions to bring home. In fact, what I came back with was a feeling of incompleteness. I knew I would have to go back again.

That feeling had started to grow from the train to Rajshahi from Rajbari.

A man in our compartment who worked in the Railways got off at Ishwardi junction. Ishwardi—a name which comes with so much history! When we were going to Naogaon from Rajshahi, someone pointed to a highway and said, this is the road Ila Mitra had taken when she was fleeing the police; he was talking about communist Ila Mitra and the Tebhaga Movement of 1949. Subrata Majumdar, retired professor of mathematics with whom I was staying recounted how he had gone to see the terracotta temples of Puthia with the researcher and writer David McCutchion. Young folklorist Uday Shanker Biswas and Abdullah Al-Mamun, both lecturers at Rajshahi University, took us to a baul akhra in Bagolpara (Durgapur) in Rajshahi, to listen to Shamsul Fokir.

Uday Shanker Biswas is truly interested in local folklore and a collector at heart. I did not know this then but understand now after several years. These photos from 2010 were sent to me in 2020.

Recordings made at Bagolpara. Singer, Shamsul Fokir. Recorded by Sukanta Majumdar on 17 September 2015

What was the connection of all this with what Bake had recorded? I am not so sure, but this was only the beginning of a journey. In the beginning you have to indiscriminately collect your shells and pebbles from the shore.

We went to Mahasthangarh in Bogura, the Sufi shrine, to find something; who knows what? There we met Mahmuda, a woman who lives on the grounds of the shrine and sings of love and pain. The next year, I would write an idea for a soundtrack called ‘Who Was Jaura Khatan?’ which would be installed as part of our exhibition in Santiniketan ‘Time Upon Time: Arnold Bake in Bengal’. But we can come to all that later.

A song by Mahmuda, in which she sings: O lord, the kind one, your love is not so good as it brings pain. Tomar bhalobasha to bhalo na.’ Recordist: Sukanta Majumdar, 15 September 2015

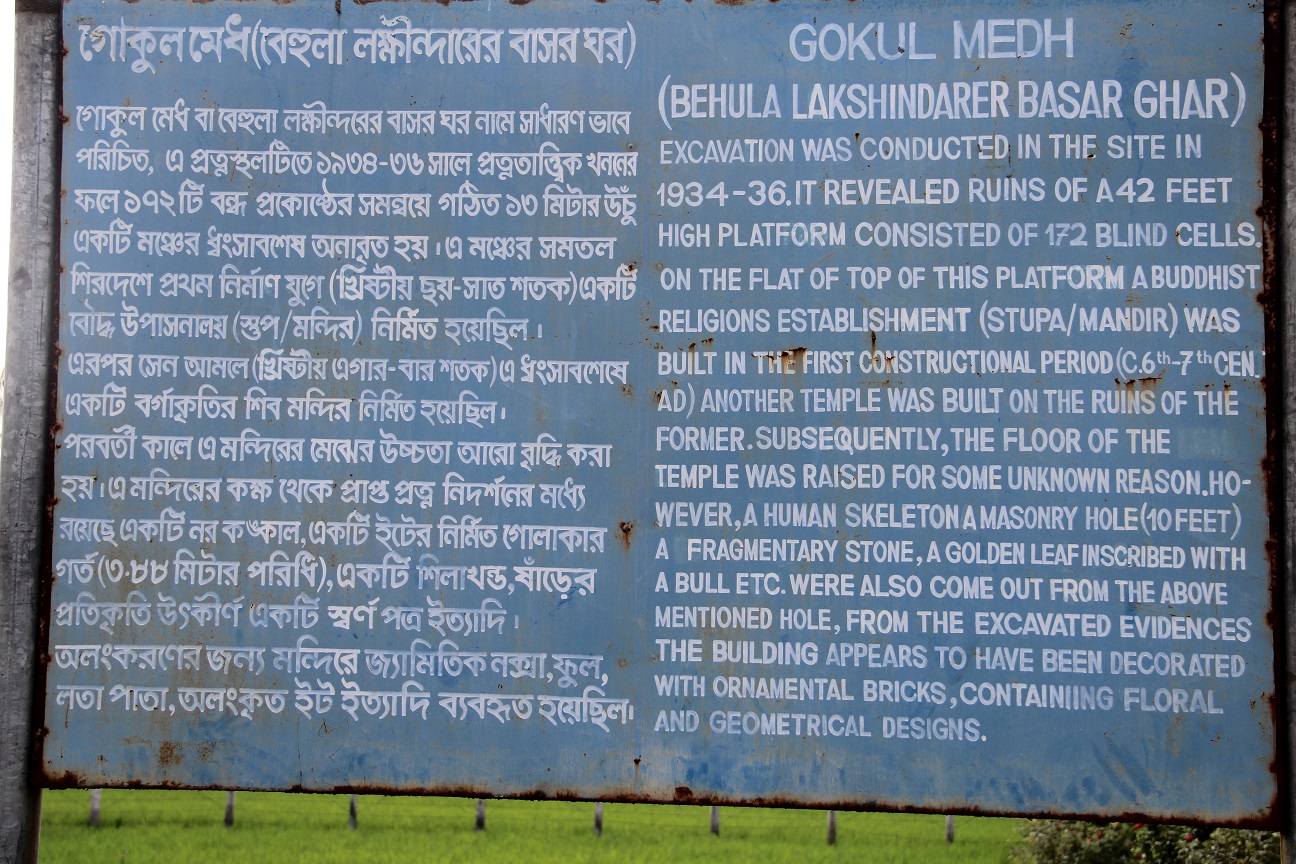

Mahmuda and her friends in Mahasthangarh share a joke. From here we went to Gokul Medh, below, a place of historical and mythological significance. There are songs and stories scattered along the way now, as they must have been in Bake’s time too.

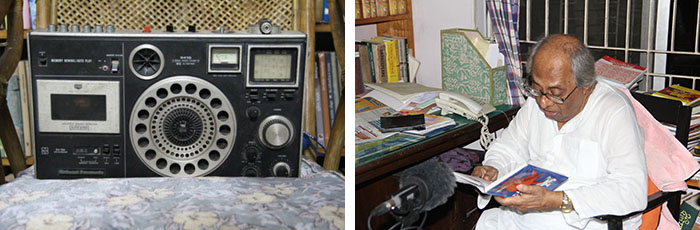

On this somewhat unfocussed trip, we were going from place to place, as if to find something–what, I did not quite know. Hasan Azizul Huq, the novelist, who had crossed the border from Barddhaman in the west to Khulna in the east first, just after Partition, and later moved through places and settled in Rajshahi, where he taught at the university, lived in the house next to Subrata Majumdar’s. We talked one evening about being torn between homes and he read from his writing for us. It was beautiful. There was an old radio cum tape recorder–a keeper and teller of tales–in the house of this fabulous storyteller. Such things always catch my eye.

Hasan bhai speaks. Recordist: Sukanta Majumdar, 17 September 2015

I met ethnomusicologist Felix van Lamsweerde (1934-2021) in his home in Santpoort Zuid. My friends, the Carnatic flautist and music scholar Ludwig Pesch and art historian Mieke Beumer took me to him.

Mieke and Moushumi at Tyler’s museum in Haarlem. Photo by Ludwig Pesch.

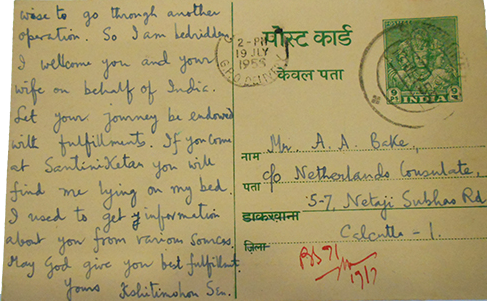

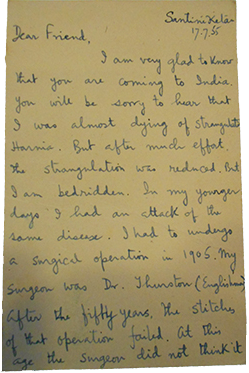

We talked about Dr Lamsweerde’s association with Arnold Bake and Jaap Kunst and his friendship with Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy, about Tagore’s visit to The Netherlands, Santiniketan and much more. Here are two clips from that conversation which took place on 30 April 2015.

All recordings on this page, also the ones in Leiden, were made by me on my Zoom H4N recorder.

Photos by Ludwig and Mieke.

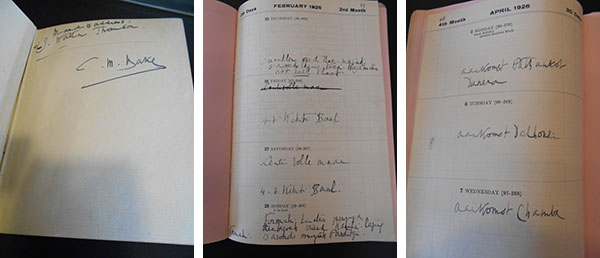

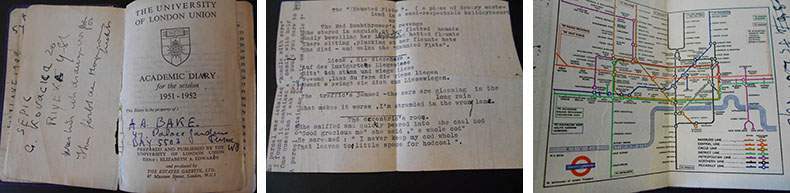

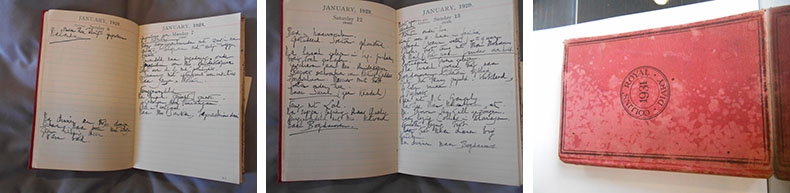

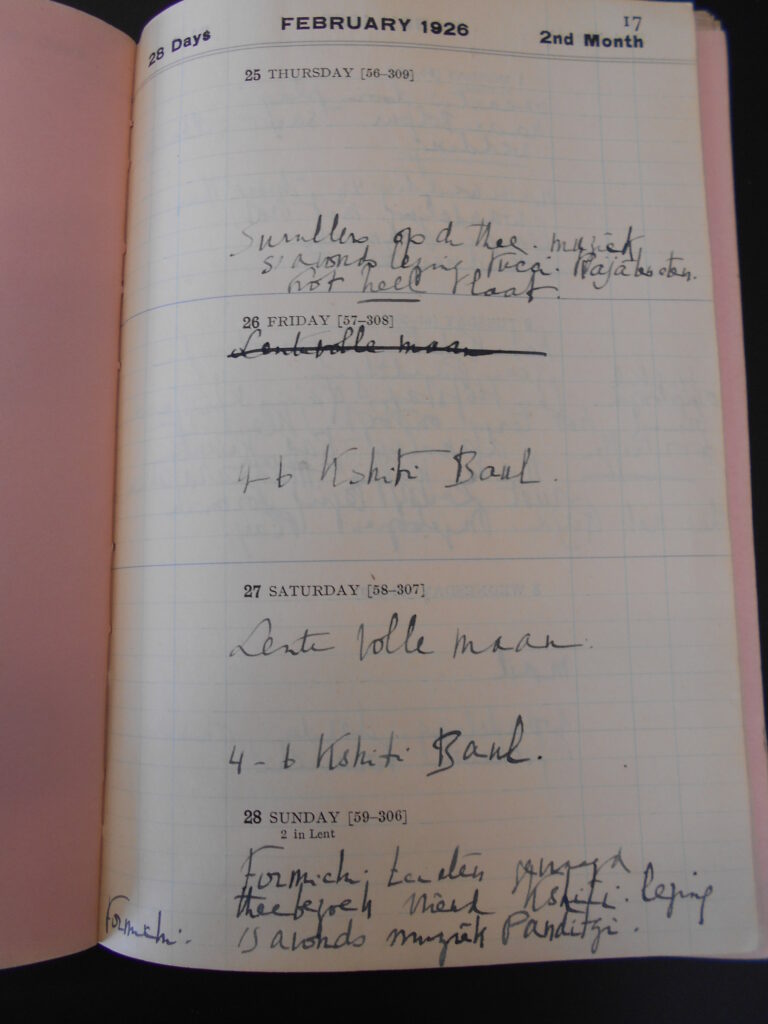

I was in The Netherlands in April-May 2015 as I had a short-term Scaliger Fellowship to study the Arnold Bake holdings of the Special Collections of the Library of the University of Leiden. I was vigorously taking photos of things to read and see later. Other than letters, photographs and other papers, I also found several diaries and notebooks of Arnold Bake and his wife Cornelia from the 1926 to 1953 period. They are mostly in Dutch, but treasures troves in themselves. I wanted so much to know what Corrie was writing about their life in Santiniketan that I had two PhD students, both Bengali, help me by reading the pages I was photographing. And then I recorded their reading. Listening now it shows our tentativeness, the fun we were having, the mistakes we were making—the recordings are pretty disarming really!

The photos are all of things carefully kept at Special Collections, Leiden University Library.

Archishman Chaudhuri was into his third year of doctoral research at Leiden when we met and spent several days reading Corrie’s diaries, sitting in the noisy cafe. This track transports me to that space and time. Archishman teaches now at McGill University in Canada.

There were bits of things tucked into the notebooks and I was so fascinated to think of the people behind them.

Byapti Sur was also a PhD student at Leiden and now she teaches at the Thapar School of Liberal Arts and Sciences. This session with her was on the last day that we met, reading Cornelia Timmers-Bake’s 1929 diary pages. The university was closed on the day so anthropologist Erik de Maaker and filmmaker and English teacher Nandini Bedi offered us a room in their house to sit and work. There were discussion over words and Erik and Nandini also joined in.

I am very grateful to Archishman and Byapti for sharing their knowledge and time with me.

Postscript

In January 2021, had sent the above note to everyone on this page to check for errors and Dr Felix van Lamsweerde had written the following email to me.

21 January 2021

Dear Moushumi,

With some delay I am happy to react positive to your request to use the interview and the photo’s as part of your thesis and on your website. Only it is not clear for me any more which photo(‘s) you selected.

Of course I realize that if I go through the audio I might sometimes think: I should have formulated my answers more clearly or otherwise, but it is now also an historical document and represents your source of information.

One little spelling mistake in your text: my house is officially located in Santpoort Zuid, and not Santpoorte.

I wish you success and also good health in this period of dangerous infections.

With warm regards,

Felix

On 31 July 2021, two days after I submitted my dissertation, Dr Lamsweerde passed away. I deeply regret that I could not show him my completed work.

Felix van Lamsweerde. Source: Internet

These are the Niyomsheba songs, a private ritual in which the Mitra Thakurs of Mainadal sing kirtan or the praise of Chaitanya and his five principal disciples who spread his teachings. In contrast to the essentially public Nandotsav singing, amplified and propagated, when the temple gates are opened for all to come and join in the celebration of the birth of Krishna, here the music is only for the insider singer and listener. Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur leads this small group of singers. They sing this same song day after day for a whole month.

Morning singing, with kartal or cymbals

Recordist: Sukanta Majumdar, 7 October 2014

Evening singing with khol or clay drums and kartal

Recordist: Sukanta Majumdar, 6 October 2014

Night singing with khol, kashor, bells

Recordist: Sukanta Majumdar, 6 October 2014

Circumambulating the temple in the morning

Video: Moushumi.

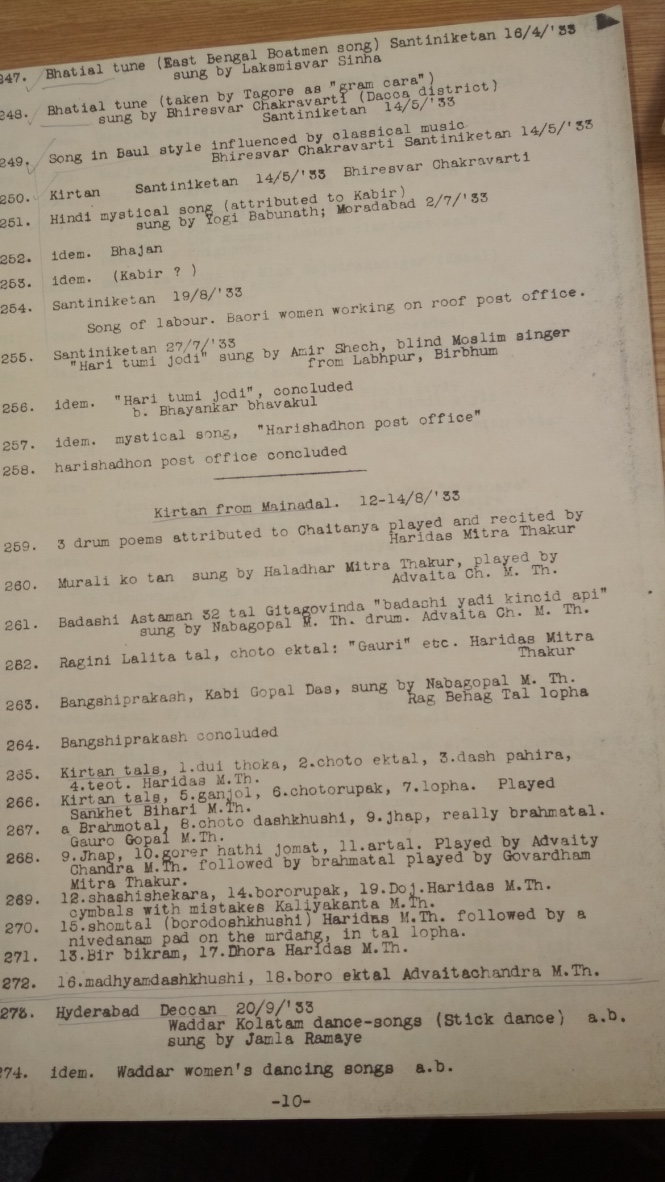

Mainadal is a place in Birbhum, also spelt Moynadal. In fact, the latter is the official spelling. Yet, I am writing Mainadal, as this is how Arnold Bake wrote in his notes. And these recordings are based on Bake’s Mainadal recordings, made between 12-14 August 1933. The British Library Sound and Audiovisual Archives has shelfmarked these recordings as C52/1908-1921; Bake India II Cylinders 259-272. The Arnold Bake Collection is numbered C52 at the BLSA. If you look at the BLSA catalogue, and search for Arnold Bake or Mainadal, you will find many traces of Bake’s original notes erased, because researchers have revised the notes. This is how the first typed version list of Arnold Bake’s wax cylinders looked.

The Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, who had loaned Arnold Bake the phonograph and cylinders to make his recordings in India between 1931 and ’34, have the same list with the same details, under the heading ‘Sammlung 46: Bake Indien II’, with the following sub-heading: ‘Dokumentation nach einer maschinenschriftlichen Originalliste. Handschriftliche hinzugefügte Passagen sind kursiv wiedergegeben. Liste unvollständig.’

Kirtan from Mainadal. 12-14/8/’33

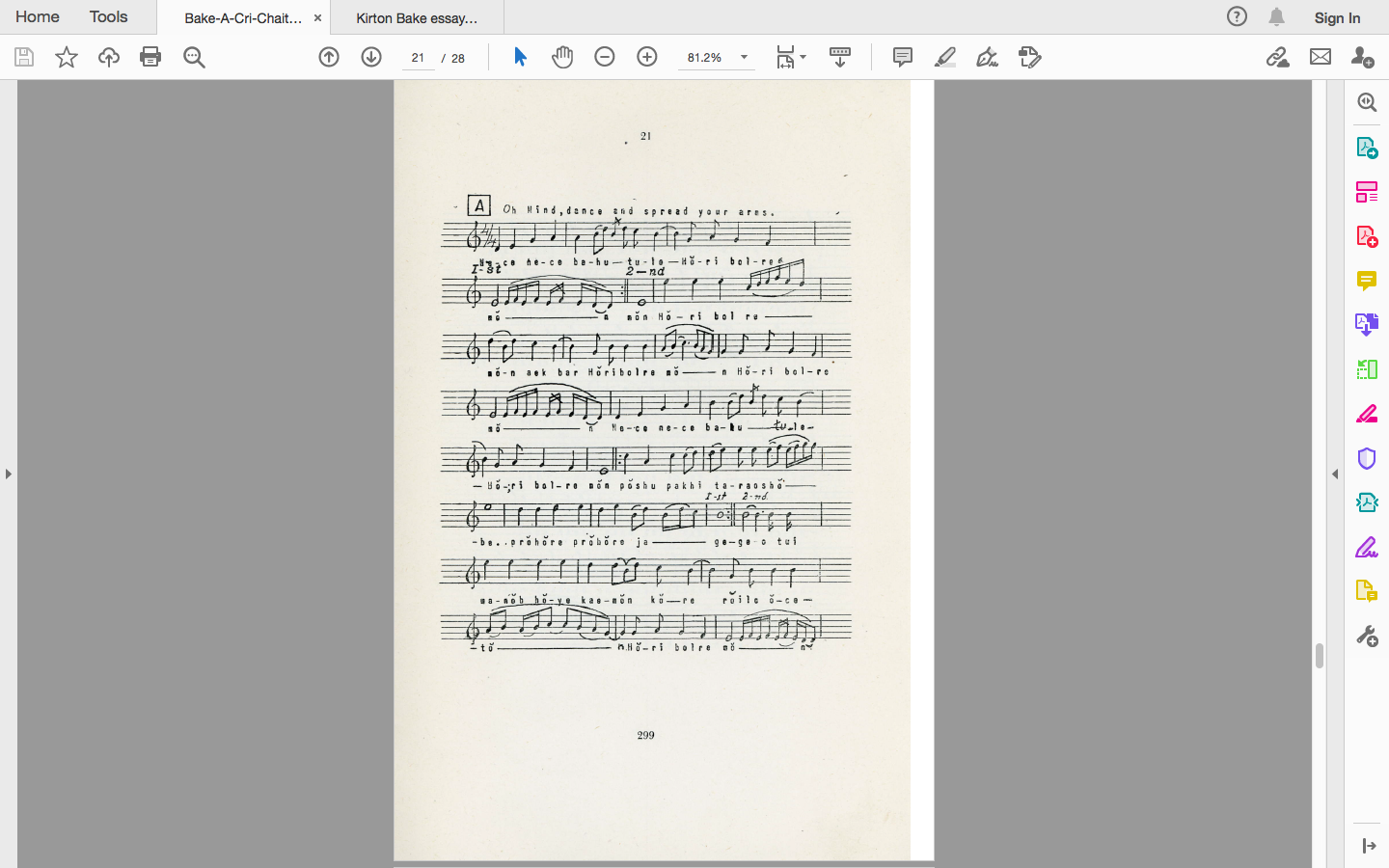

| 259. | 3 drum poems attributed to Ghaitanya played and recited by |

| Haridas Mitra Thakur | |

| 260. | Murali ko tan sung by Haladhar Mitra Thakur, played by |

| Advaita Ch. M. Th. | |

| 261. | BadashiAstaman 32 talGitagovinda “badachiyadikincidapi” |

| sung by Nabagopal M. Th. drum. Advaita Ch. M. Th. | |

| 262. | Ragini Lalita tal choto ektal: “Gauri” etc. |

| Haridas Mitra Thakur. | |

| 263. | Bangshiprakash, Kabi Gopal Das, sung by Nabagopal M.Th. |

| Rag Behag Tal lopha | |

| 264. | Bangshiprakash concluded |

| 265. | Kirtan tals, 1. dui thoka, 2. choto ektal, 3. dash pahira, |

| 4. teot. Haridas M. Th. | |

| 266. | Kirtan tals, 5. ganjol, 6. chotorupak, 7. lopha. Played |

| SankhetBihari M. Th. | |

| 267. | a. Bhramotal, 8. chotodashkhushi, 9. jhap, really brahmatal. |

| Gauro Gopal M. Th. | |

| 268. | 9. Jhap, 10. gorerhathijomat, 11. artal. Played by Advaity |

| Chandra M. Th. followed by brahmatal played by Govardham | |

| Mitra Thakur. | |

| 269. | 12. shashishekara, 14. bororupak, 19. Doj. Haridas M. Th. |

| cymbals with mistakes Kaliyakanta M. Th. | |

| 270. | 15. shomtal (borodoashkhushi) Haridas M. Th. followed by a |

| nivedanam pad on the mrdang, in tallopha. | |

| 271. | 13. Bir bikram, 17. DhoraHaridas M. Th. |

| 272. | 16. madhyamdashkhushi, 18. boroektalAdvaitachandra M. Th. |