In Search of Nabadwip Brojobashi

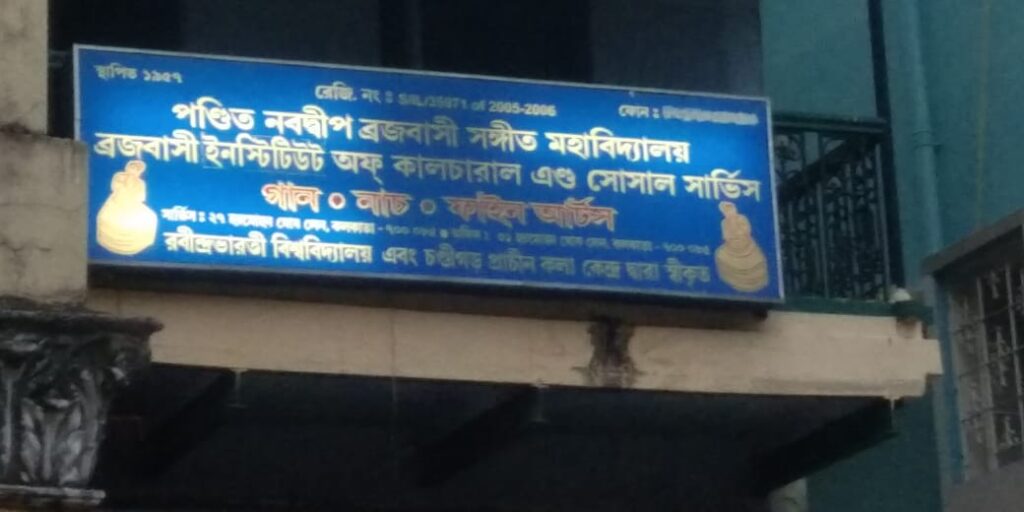

On 15 May 2017, Bob van der Linden, Arnold Bake’s biographer had written the following email to me: ‘By the way, did you already visit “Pandit Nabadwip Brajabasi Sangit Mahavidyalaya”, 31 Haramohan Ghosh Lane, Calcutta? Perhaps they have something there (letters, photographs, stories)? I am still dying for a photograph of Nabadwip Brajabashi to include in my book. Also of course it would be great for your work. Love the idea of going there together… but unfortunately I won’t be in Calcutta, at least before November.’

(There is a whole range of spellings for both Nabadwip and Brojobashi—different scholars use different spellings. Bake wrote in one way, the family writes another, Bob van der Linden and Eben Graves in yet other ways. So, I too took the liberty and wrote my own way, more to suggest the sound of the name. Braja is more upcountry sounding, in Bangla we tend to have a more round sound).

I did indeed go to the house of Arnold Bake’s kirtan guru on 21 December 2017. The experience was quite curious, but I could not follow it up with more, and for my second trip I had to wait till May 2022, about which I have written in my post-script note below. For a long time I did not have much material to share on the website, barring a few photographs.

The original house on 31 Haramohan Ghosh Lane near Beleghata in east-central Kolkata must have been different from this apartment house, but some signs of the past are still intact.

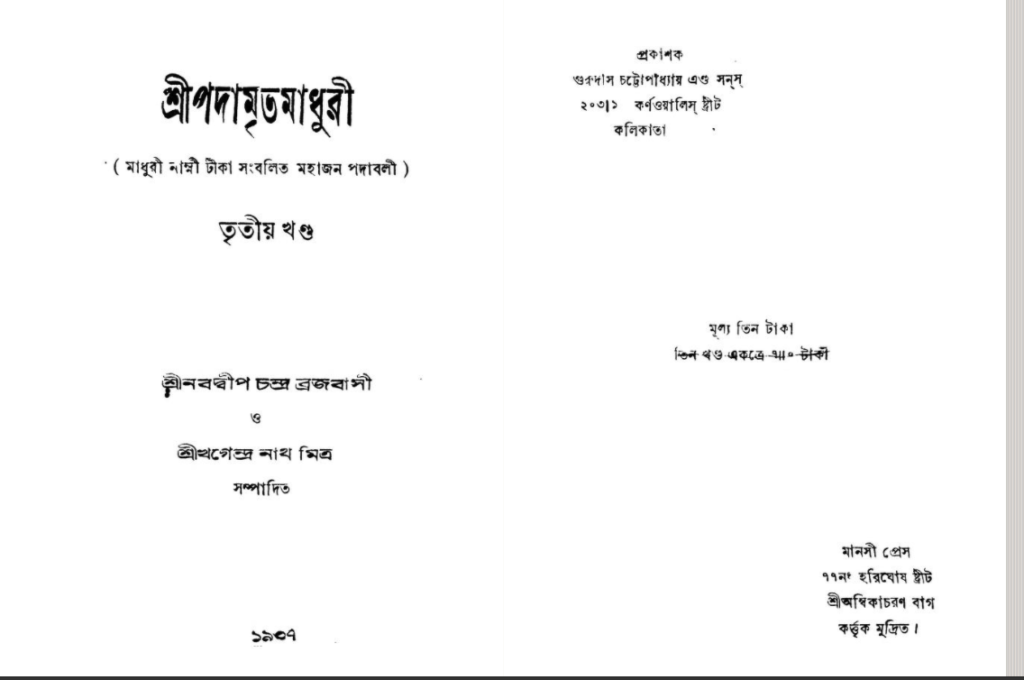

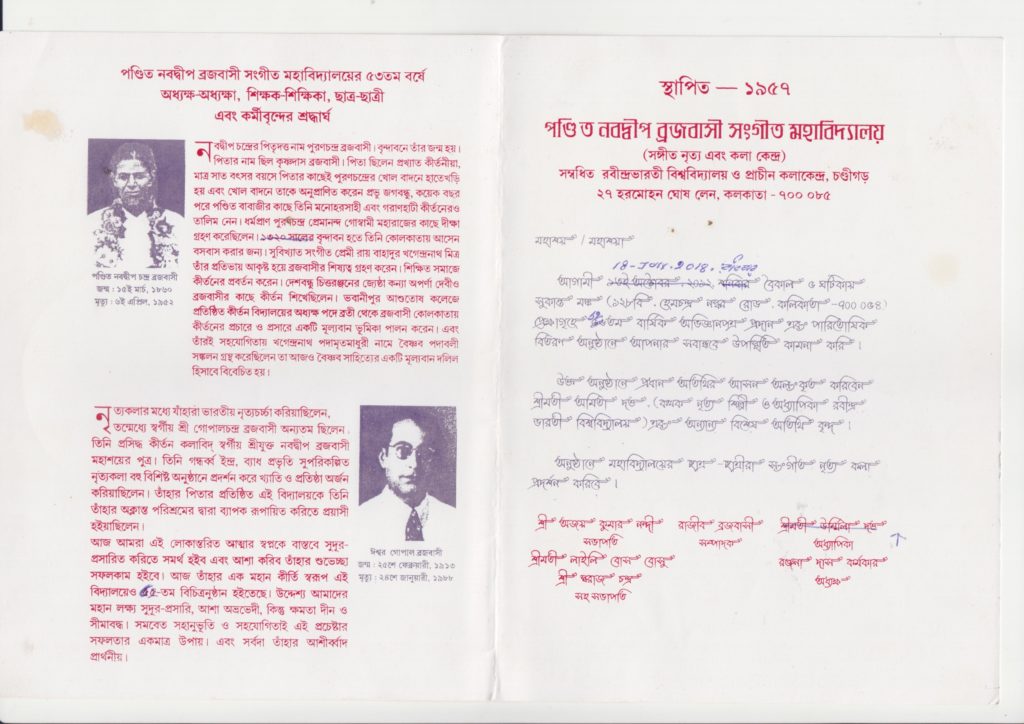

Bob van der Linden’s biography of Arnold Bake came out from Routledge, in 2018. In it he wrote, ‘During his kirtan studies, Arnold became well acquainted with Professor Khagendranath Mitra (1880–1961) of the University of Calcutta, who studied the genre extensively. Indeed, he argued that saving it from extinction, and specifically from the hands of courtesans, “should be a national commitment of all Bengalis”. In addition, Bake came to know Mitra’s kirtan guru Nabadwip Brajabashi, who was born in Brindavan to a family of temple priest- proprietors. [… ] In general, Mitra and Brajabashi are credited with bringing the devotional genre of Vaishanavite kirtan to the attention of the Bengali elite (bhadralok). They not only standardized and shortened songs, but also connected the genre with a base of Sanskrit aesthetic theory to make it respectable for the bhadralok. As a matter of fact, Brajabashi was especially responsible for this. Together, they compiled an anthology of kirtan songs, Sri Padamrita-Madhuri or “The Sweet Elixir of Verse” (1910). At the time, Bake had only a few lessons with Brajabashi and made some recordings of his singing. During the early 1940s, however, he would study with him more extensively and embrace him as his true guru.’ (p.29)

Sri Padamrita Madhuri by Khagendranath Mitra and Nabadwip Brojobashi

In 2017, ethnomusicologist Eben Graves who has a special interest in South Asian devotional music, wrote an essay entitled ‘Kirtan’s Downfall: The Sadhaka Kirtaniya, Cultural Nationalism and Gender in Early Twentieth Century Bengal’, about Khagendranath Mitra’s ‘mission’ to ‘establish padavali kirtan in bhadralok society. Mitra was a key actor in the formulation and promotion of the image of the sadhaka kirtaniya, a multivalent term that referred to a kirtan musician (kirtaniya) who was a sadhaka or “one who performs sadhana”.’ Brojobashi, Mitra’s guru, was such a religiously devout, musically skilled musician, who became part of a process of classicisation that worked to ‘distance Bengali kirtan from a group of female courtesan singers who performed in a popular devotional musical style known as dhap kirtan.’ This was a project in cultural nationalism and identity formation, in which Mitra played a leading role.

There were some elite women who fitted this image of the ‘sadhaka kirtaniya’ too. I am thinking of Chhabi Bandopadhyay, a student of Nabadwip Brojobashi. When we went to her shishya Seema Acharya’s home in February 2016, there was the shelf dedicated to Seema’s gods and gurus, on which stood the framed photo of Chhabi Bandopadhyay, alongside Baba Loknath, Anandamoyi Ma and idols of Radha-Krishna.

The shrine in kirtaniya Seema Acharya’s home. Kolkata, March 2016. Photo: Jan-Sijmen Zwarts.

Parallel to this, I am thinking of my visit to 31 Haramohan Ghosh Lane, where Nabadwip Brojobashi’s grandson, Rajib Brojobashi now lives. He wasn’t home that evening, but his wife opened the door. She said her husband was out for political work and her daughter was at work in Rajarhat-Newtown, in the I-T hub of Kolkata. She asked us to come in. As we entered the drawing room, some beautiful blown-up black and white photos of a most glamorous couple welcomed us from the wall. They looked like fifties’ film actors. ‘They are my in-laws,’ the woman explained. They were Nabadwip Brojobashi’s son and daughter-in-law who were professional dancers and travelled to many countries with their troupe. Gopal Chandra Brojobashi and his wife.

Rajib babu’s wife called him and introduced us over the phone; ‘Ram Ram,’ he greeted me.

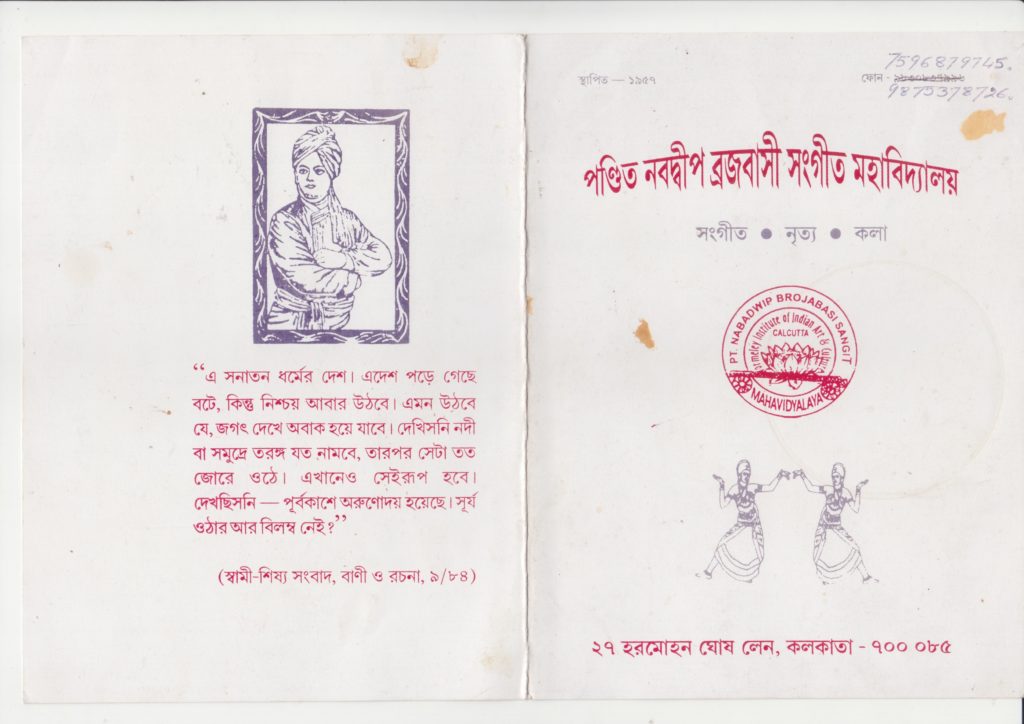

Programme of annual concert of Pandit Nabadwip Brajabashi Sangit Mahavidyalay, 2018

Rajib babu’s wife was unprepared for our visit (I went with my old friend, theatre director Sudipto Chatterjee and his actor wife Anwesha, who live in the neighbourhood), but she was also very kind. She did not know how to entertain us, what to say about her husband’s paternal grandfather. She told us that after the old building was taken down and this apartment house was built, the old temple was shifted to the top floor and the gods were newly housed there. We could see the temple if we liked, she said. So, we went up and she opened the collapsible gates and the locked door of the temple, and turned on the light. A Chinese Laughing Buddha with LED lights, waved and greeted us, while a chime started to play. There, among the many gods and goddesses, were photos of Nabadwip Brojobashi, Balak Brahmachari as well as Brojobashi’s dancer daughter-in-law.

Temple on the terrace, 31 Haramohan Ghosh Lane, Kolkata 700085

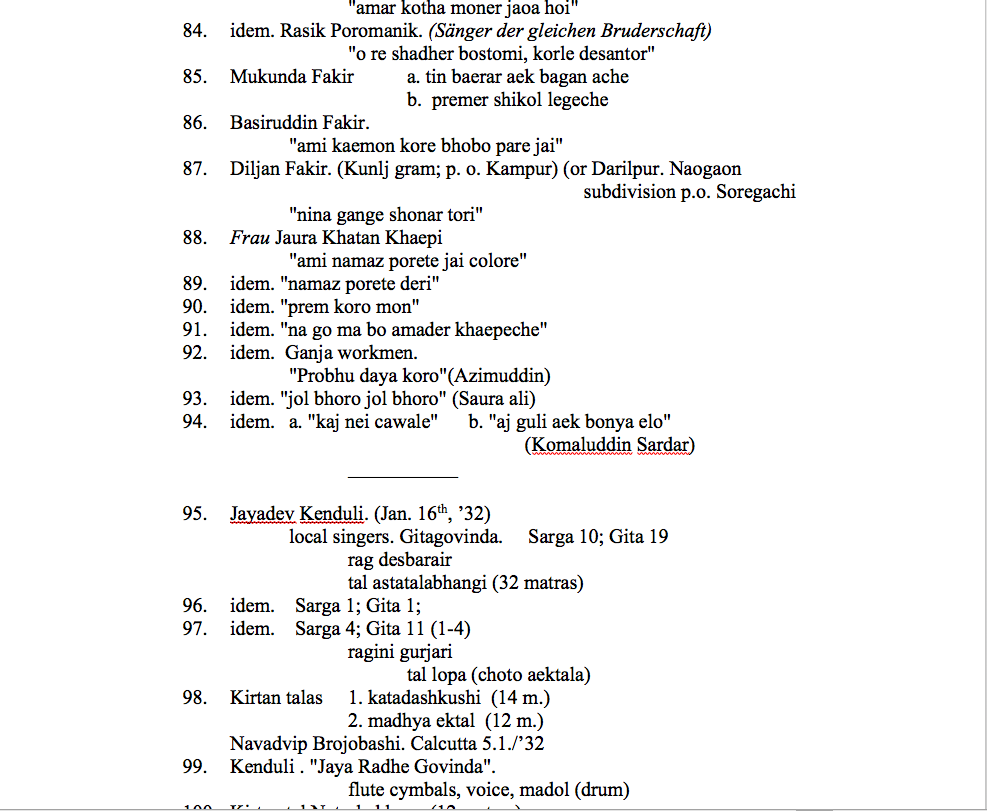

There is so much left to know and I do want to go back to 31 Haramohan Ghosh Lane. I sense a continuity in this story of nation-building. From Vrindavan, to singing and teaching in Calcutta’s elite circles of the Rai Bahadurs through representing India as cultural ambassadors to the ‘Ram Ram’ greeting and working for global capital in Sector V, here is a story of a journey of not just a family but also of a nation. A story which begins for us in the circular motions of a wax cylinder numbered 98, Bake Indien II of the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, recorded in Calcutta on 5 January 1932.

Arnold Bake cylinder documentation from Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv. Copy of file shared with me in 2016.

Postscript, 15 May 2022

Over four years have passed since I went to Beleghata, in search of Nabadwip Brojobashi. But all along I knew that I would have to go back to his home. Then, on 15 May 2022, Sunday, I finally went to meet Rajib Brojobashi, Nabadwip Brojobashi’s grandson. I did not know where he would be, as I was not being able to reach him on the phone number I had. So, I just took a chance. By now I have submitted my thesis and there is no real hurry to finish anything.

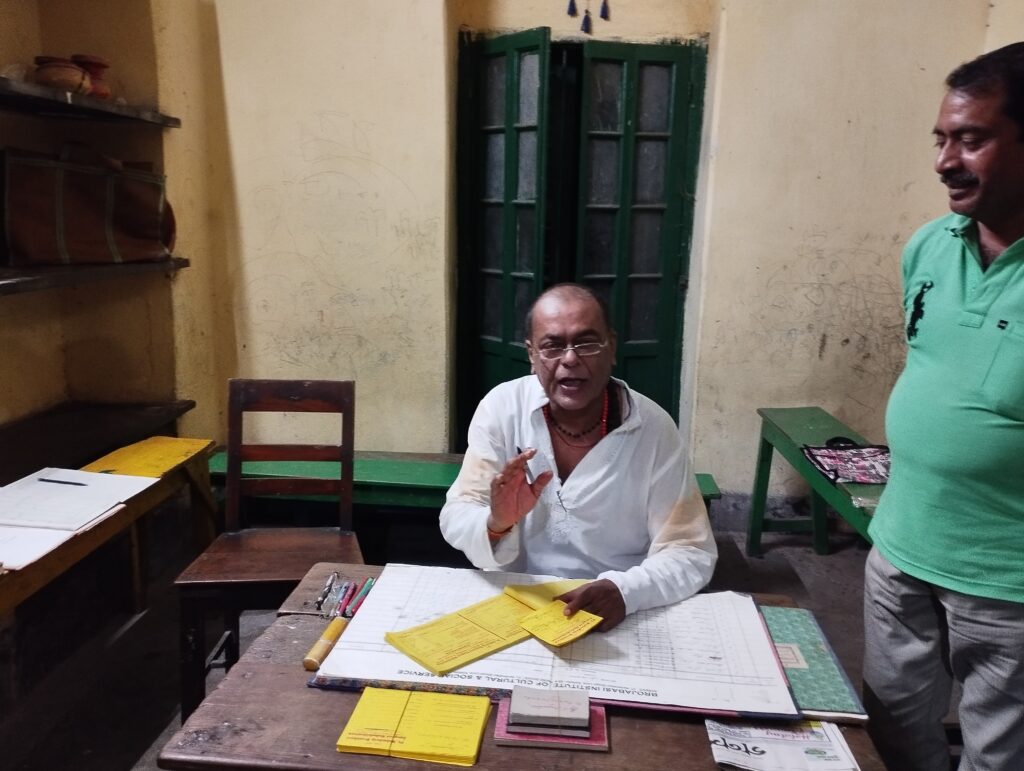

I went with a friend to Haramohan Ghosh Lane and as I was a little confused about the exact location of the house, I asked people in the neighbourhood and they said I would find Rajib babu in his music school. So that is where I went. He was not expecting to see me but he was very warm and generous with his time, although he did seem awfully busy. He said, it was good I had come on a Sunday, as he worked in the school during weekends and did not leave the neighbourhood. Rest of the week, there was no knowing where he could be. Although he was retired now from his government job in the tax department, he had organisational work to do, which was likely political too. But I did not ask such questions.

Pandit Nabadwip Brojobashi Sangit Mahavidyalay, 27 Haramohan Ghosh Lane, Beleghata, Kolkata 700085

Rajib Brojobashi, who runs his father’s school now.

I explain my work to Rajib babu, tell him that I am interested to know about the trajectory from his grandfather at the turn of the twentieth century, through his own parents, down to him in his own time. Rajib babu says he will help me in whatever way he can, with photos and other details. He talks about their family of kirtaniyas, who hail from Vrindavan and the precious idol of Sri Krishna that one of their forefathers had found lying in a forest, and which Nabadwip Chandra’s father had brought with him when they migrated to Kolkata.

Rajib babu talked about his plans, with the school, about the asrams I could go to, to learn more about his grandfather and how he would take me to those places. His father had set up the school in 1953, a year after Nabadwip Borjobashi died. It was first called the Institute of Indian Art and Culture. Then, on the advice of kirtan scholar Khagendranath Mitra, historian Pratap Chandra Chandra and others, it was named after Nabadwip Borojobashi. He talked about how they came to set up their school in this beautiful old building. He talked about his mother’s family, his aunts who were all into dance and cinema. He talked about Partition and killings in Calcutta; stories he had heard from others. At the end of the conversation, it felt like there was so much left to know. And we made plans for more visits. Important people from the film industry and the world of politics, performing arts and police officials were connected with their lives from the time of Nabadwip Brojobashi down to the present time. I have to keep going back, as I have done with many of the other Bake recordings. One thing remains common in all these stories. It is the delight of listening to the voice of the ancestor, buried under the surface noise of the cylinder. As he listened, Rajib babu said, ‘I am getting goosebumps.’

Video recorded by Subrata Sarkar, 15 May 2022

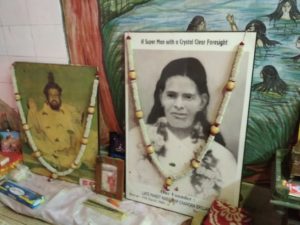

Then Rajib Brojobashi took me home and I met his daughter Rakhi, who works for the IT company, Wipro. She was working from home on her computer. Like the first time I went, I was once again struck by the glamorous portrait of his parents, Gopal Chandra Borojobashi and his wife, Asha. I was struck because it stood out among the rest of the photographs and also the general ambience of the room. Above his parents was a framed photograph of Nabadwip Brojobashi, decorated with a saffron silk scarf. (I wonder why Arnold Bake never photographed his teacher.) On the right-side wall, there were portraits of various heroes of Bengal, red vermillion smeared on their foreheads—Swami Vivekananda, Netaji Subhas Bose, Sri Aurobindo. The rest of the wall was covered with photographs from functions in their schools and other events.

Recorded on my Zoom H2N on 15 May 2022.

- Manoharsai from Sumati Devi of Manipur

- Manipur Univisited

- Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur Explains Bake’s Kirtan Recordings, 2021

- Found Film: Janmashtami and Nandotsav in Mainadal, 1994

- Kirtaniya Seema Acharya Listens to Olly

- Olly Weeks Reads Bake’s Kirtan Notation

- In Mongoldihi, November 2015

- The Niyomsheba Songs, October 2014

- First Time in Mainadal, August 2014