Found Film: Janmashtami and Nandotsav in Mainadal, 1994

These are 17 clips of varying length of found footage from 1994, which was given by the Mitra Thakurs of Mainadal to The Travelling Archive, after several visits to the village between August 2014 and January 2016. Our visits, with recordings of their ancestors’ voices from archives and records released in Europe, about which the family was not aware, aroused in this old family of kirtan singers, a certain renewed interest in their past.

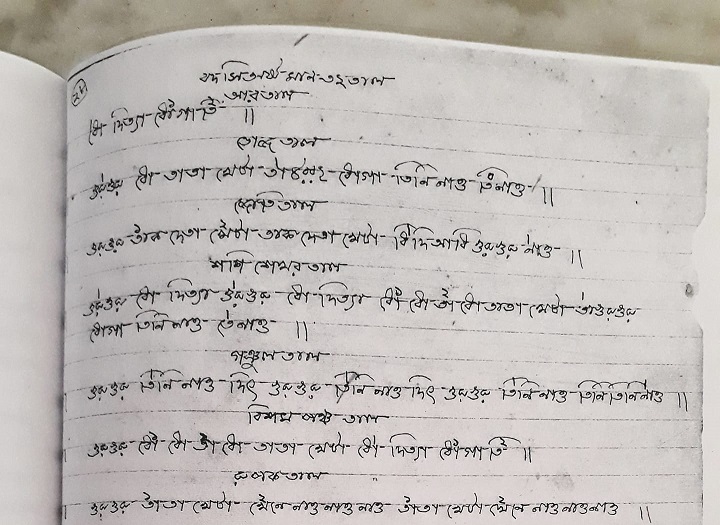

This page is a from a notebook of one of the Mitra Thakur elders, Sakalananda Mitra Thakur (1915-1989). He was a master khol player and here he has written out the bols (the rhythmic pattern) of the many tals or beats which accompany the song ‘Badasi’, which, interestingly, Arnold Bake had recorded in both Mainadal and Kenduli in 1933. We do not know when this notebook entry was made. Milan Mitra Thakur has written about his uncle Sakalananda thus: In our family, as much as I have seen, most of those who excelled in singing and khol playing never stepped into any formal school. The reason is that, the time when children go to school with books in bags slung over their shoulders, our elders would carry their drums and accompany their guardians to kirtan sessions; they sang and played along with them. Thus, my uncle Sakalananda never went to school, yet his neat and beautiful handwriting amazes me. আমাদের পরিবারে, আমার দেখা গান বাজনায় যাঁরা পারদর্শী ছিলেন, অধিকাংশ তাঁরা স্কুলের মুখ দেখেন নি ; তার কারণ যে বয়সে সবাই বই কাঁধে নিয়ে স্কুলে যায় সেই বয়সে, এঁরা কেউ খোল কাঁধে নিয়েছেন কিংবা অভিভাবকদের সাথে গানে গলা মিলিয়েছেন। তেমনি আমার জ্যেঠা, খোলবাদক সকলানন্দ মিত্রঠাকুর … আমার জ্যেঠা স্কুলে যাননি কিন্তু তাঁর সুন্দর হাতের লেখা দেখলে অবাক হই। জ্যেঠা শেষ বয়সে তাঁর একটি খাতায় খোলের সমস্ত বোল এবং তালের অঙ্কপাত করে লিখে রেখে গেছেন যেগুলি আমাদের ঠাকুরবাড়ির বিভিন্ন উৎসবের গানে এবং মনোহরসাহি ময়নাডাল ঘরানার কীর্তনে বাজানো হয়।

This matter of digging into their own past is interesting. In a sense, the family has never been disconnected from its past, because what the Mitra Thakurs sing comes from a past and moves into a future. However, till recently, there was not much of a conscious effort to keep records of a particular time within the flow of time; I think they did not feel the need for it either, because they were part of that flow. They could more or less take preservation and continuity for granted. Their lives had little connection with the world from which Arnold Bake came, with its growing interest in knowledge-production through recording and archiving and the power it generated. Perhaps they had encountered the camera, but even if they had a longing to be photographed, where would they find the means? The voice recorder would be a greater rarity.

Arnold Bake had met the Mitra Thakurs for the first time in 1931 in Ilambazar, during a communal ‘naam sankirtan’ singing and dancing event, where they gave him their address and invited to come to their village during Nandotsav. Bake could go after two years, in August 1933. This must have been the Mitra Thakurs’ first encounter with the recording machine and they were very keen to sing to the horn of the machine, as Bake wrote in his letters home, yet they might not have cared so much for what happened after they sang to the horn.

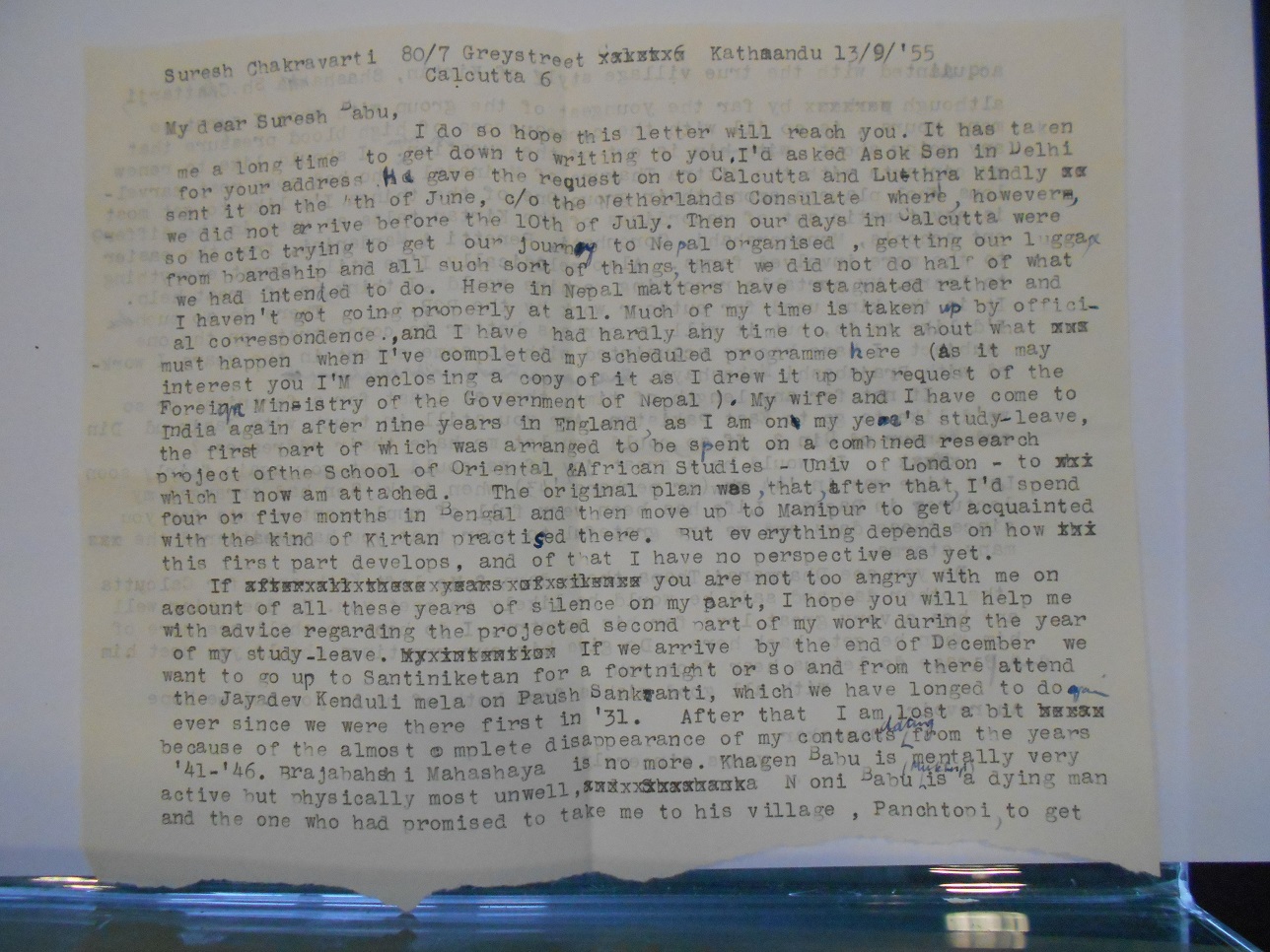

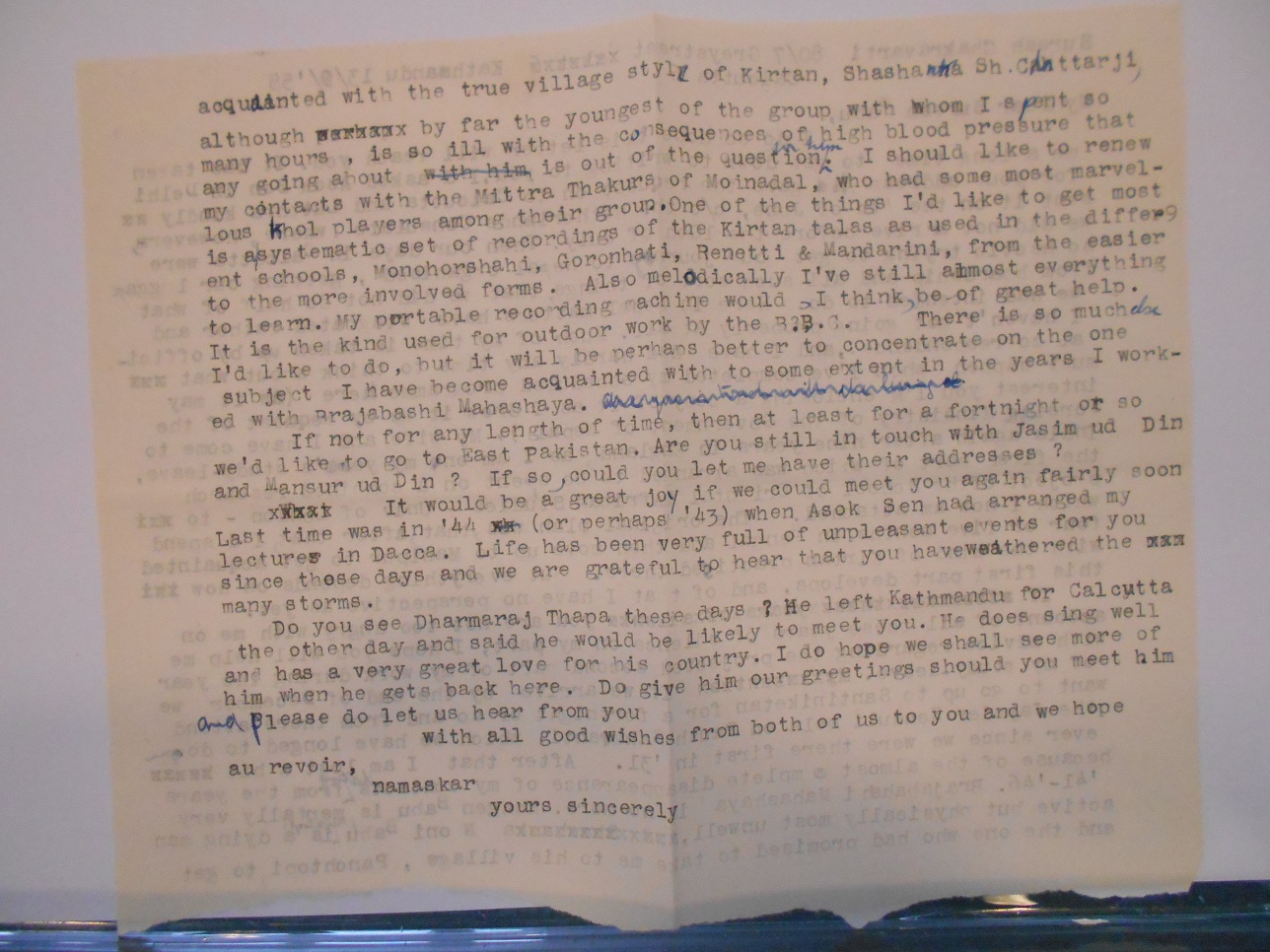

There is a highly interesting paradox in this story. Kirtan was so central to Arnold Bake’s life as a scholar and singer, till the end he longed to return to Mainadal, to learn more, or go to Manipur to learn about their practice of kirtan.

Arnold Bake letters to Suresh Chakravarti written in 1955 in which he wrote about his interest to return to kirtan studies. Image courtesy: Special Collections, Leiden University Library, photographed by me while working as a Scaliger Fellow in 2015.

Yet, when Bake went to Mainadal, he made his recordings and left, and he hardly left any traces of his visit. At least, there was no memory in the village or the family of such a visit. I think that once they learned from us about Bake’s recordings from Mainadal, the family realised that not only by passing the songs from one generation to the next, but another way of memorialising and preservation was also possible. The archive entered the consciousness of this place which itself was an archive. It kindled in the family an urge to search and look for old records. This video recording was one of the things they found and shared with us.

It shows, however, that the need to record, archive and perpetuate was being felt much before our visit. The Mitra Thakurs were talking about the urgent need to preserve the tradition way back in 1994. This video recording had been initiated by Nandalal Mitra Thakur, who had something of a historian’s instinct and wrote a book about religious rituals and songs of Mainadal. Nandalal’s son, Milan, the artist who has over the years become a close friend of The Travelling Archive, has taken a lead in digging the family’s history for things he considers worth keeping. It is he who had digitised these VHS tapes, from which we have created these seventeen short pieces.

|

Introducing the songs, singers and listeners of Mainadal. | |

|

Kirtan | |

|

Bhog or communal feeding | |

|

Mela |

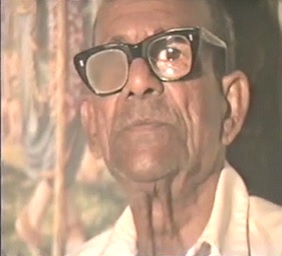

Those who sang a hundred years ago are no more, there are no recordings or photographs either. Those who had seen them are also about to depart. What do we do? In this footage, there are musicians Arnold Bake had recorded in 1933, as well as some whom we met in 2014 and later. Hence, there is a continuity here, of almost a hundred years, of a family that has been singing kirtan for five centuries.

|

Dhol players Jiten Badyakar and team | |

|

Gobindagopal Mitra Thakur (whom Bake had recorded) | |

|

Kaliakanta Mitra Thakur and sons (whom Bake had recorded) | |

|

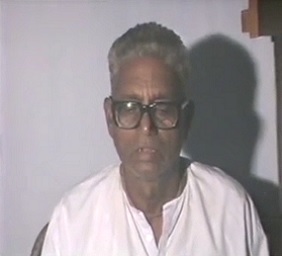

Nandalal Mitra Thakur | |

|

Manikchand Mitra Thakur (whom The Travelling Archive recorded) |

I believe that there is a time for such ‘discoveries’–it is only after years of excavation that we reach the precious thing buried under the ground. This film was lying in one of my hard drives, and I was not even aware of its existence. It is only now, when I was finishing my thesis and going through the collection which has built up over the years, that I ‘found’ this material. In fact, I do not think I would have understood the value of this material without these years of preparation. Here I have presented the clips in my own way, adding words, images and sounds from my time as well as from Bake’s time and from other times before and beyond us. They are self-contained units, but they are also parts of a larger narrative. Hence, from Clip 1-17, they are chapters of a story, leading to many other stories.

|

Prabhat Mitra Thakur | |

|

Nandotsav arati and interview of Krishnagopal Mitra Thakur and sons | |

|

Drums as deity | |

|

‘O he Gouranga’ | |

|

Nitai dances, ‘Byom byom Shib nache’ |

What Milan Mitra Thakur had given to us, and of which he did not keep a copy, were DAT files which had to be converted to mp4s. Then I sent the mp4s back to Milanda and he wrote a basic introduction and timeline for me. Based on his information, I found the edit points and wrote a ‘script’ of sorts. I had in mind the form and style of the silent films of Arnold Bake. Finally, based on my ‘script’, Kaushik Hafizee edited these 17 short pieces. Here we have recordings of Arnold Bake from 1933 as well as The Travelling Archive’s recordings through the years from 2014, and recordings and other material from the archives of the Mitra Thakurs from the 1970s. The Dutch letters of Arnold Bake, as always, were translated by Jan-Sijmen Zwarts.

|

Nandotsav song | |

|

Invoking the ancestors | |

|

Final prayer ‘Sachir nandan nath’ |

Post Script, 30 March 2023, 8:30 pm

A thought has been on my mind about the dance ‘Byom byom Shib nache’, clip number 14, above. I was thinking, how come the Mitra-Thakurs, being such deep Vaishnavs, sing this song to Shiva? Was there no conflict here between Vaishnava and Shakta practices? The thought occurred to me, unlettered as I am in matters of religion. I had this conversation in the afternoon of 30 March 2023 with my all-time guide in Mainadal, Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur, and here is what he said on the phone.

Nirmalda explained to me that there was no problem in singing the song of Shiva, or Shib, as they see Shib as a param Vaishnava or a highest devotee of Krishna. How come? I asked. Their Shib was not Tantric, he told me. The way he spoke, it appeared to me that it was a matter of unquestioned belief. I found it too complex to understand. Nirmalda said we would have to discuss this in another session some other day. In this song that we are singing, Nirmalda said, we are not only talking about the dance of Shib (byom byom Shib nache) but of the entire heaven and earth. Everyone is rejoicing the birth of Krishna. Brahma is dancing, Indra is dancing, Shiva is dancing, as the cowherds are also dancing–there is no end to our ananda (happiness). Then he sang some more songs about Shib from their own kirtan repertoire. For example–and here he was citing a composition of Chandrashekhar of Kandra, Bardhaman–there is this song when Ma Yashoda (Jashoda in Bangla) is typically afraid to let her child Krishna go out with the cowherds. Krishna’s friend Sridama (or Sreedam as we say in Bangla) tells Jashoda that there are these protectors who are around when Krishna goes to the field or the woods, one is a strong man and appears to be in rage; he is covered in ashes. The cowherds have no idea who this might be. He comes riding a bull and on his left side is a woman. He offers flowers and the water of the Ganga to our little Gopal. Ganga, in Vrindavan? Jashoda asks. Yes ma, Sridam says, it is strange, He has matted hair, shakes his head and water keeps flowing (he is referring of course to the story of the birth of the Ganga from Mahadev or Shiva’s dreadlocks) and with that they wash your Gopal’s feet. And the woman? Well, ma, you are so proud of your wealth of cows and how you can feed curd to your boy, but you can do that with only two hands, can’t you? With one hand you lift your child, with the other you feed. This woman can feed him with her ten hands! So, don’t you worry ma, they are there to protect our little Krishna, there can be no harm.

It was a beautiful song that Nirmalda was singing. He moved at ease as he sang and talked. He told me about some other padakartas (composers) and their compositions, namely Shashishekhar of the same Kandra family and Shibai Das (whose origins he could not tell me). I listened but it is not easy to grasp the depth of this knowledge which they have been holding for generations. They wear it so lightly. As always, I was truly glad we had this conversation centred around the beautiful, dancing body of Nityananda Mitra Thakur whose charm does not wear off for me and whom I cannot help missing, even regretting we did not make the most of our very brief encounter with him. Yet, it is also in such moments when we talk about him that Nitai comes alive and stands in our midst. I see him dancing and singing in joy, as the one who always stood out in a crowd.

Post Post-Script, 30 March 2023, 10:39 pm

A message from Milan Mitra-Thakur, after he read the above note. I had called him first this morning to ask about the Shiva dance and he asked me to talk with Nirmalda.

তখন মনে পড়ল না , কীর্তনে রাসলীলা গানের শেষে শিব নৃত্য হয়, নিতাই এই শিবনৃত্য করতে করতেই আসরে মারা যায়। রাসলীলায় শিব নৃত্য কেন হয় সেটাও নির্মলই বলতে পারবে।

Nirmalda and Milanda are cousins. Milanda guides me in matters relating to archiving and the history of Mainadal, Nirmalda teaches me things about their songs. Now Milanda has written: ‘I did not remember at the time when you called. But there is a dance of Shiva that happens at the end of our Rasleela kirtan, and this is what Nitai was dancing, at the close of Rasleela [in 2015] when he collapsed on the floor and died. Why they dance the Shib-Nritya at the close of Rasleela is also something Nirmal will be able to tell you.’

I am dumbstruck to read this message.

- Manoharsai from Sumati Devi of Manipur

- Manipur Univisited

- In Search of Nabadwip Brojobashi

- Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur Explains Bake’s Kirtan Recordings, 2021

- Kirtaniya Seema Acharya Listens to Olly

- Olly Weeks Reads Bake’s Kirtan Notation

- In Mongoldihi, November 2015

- The Niyomsheba Songs, October 2014

- First Time in Mainadal, August 2014