Helim Boyati and the Art of Melodic Reading

On 13 October 2019, I went with sound recordist Sukanta Majumdar to meet Helim Boyati of Rajibpur, Netrokona, to learn from him about jarigan and puthi-path, both forms of narrative song, the latter called melodic reading by David M. Kane in his detailed study of the form and its usage in Sylhet. Helim Boyati, a living master of these forms of narrative song of this region, talked about their current practice and described how things used to be in the past. He talked more about jari, but he also read out a puthi for us. I have discussed Helim Boyati’s jarigan recordings in my sub-chapter on Imam Bux Boyati in the Santiniketan and Others chapter. So we can read and listen to this sub-chapter in conjuntion with that one.

Map of the places from where these songs and our singers came, with a page from an old puthi placed as an inset. Created by Purba Rudra

There was a sense of fullness, of a pitcher brimming with songs in 78-year-old master singer Helim Boyati’s recollection of jarigan in the Mymensingh-Kishoreganj-Netrokona region in the early days of his career in the days of his youth, just after the Shongram or the Liberation War of Bangladesh of 1971.

Pages from Sakkhatkare Bangladesher Folklore Sadhak, Vol. 1 (Conversations with some folklorists of Bangladesh), compiled by Saymon Zakaria and published by Bangla Academy, Dhaka.

We talked mainly about Arnold Bake’s recording of jarigan, when Imam Bux Boyati and his team from Atharobari, Netrokona, had visited Suri in Birbhum in the west of Bengal in 1931-32. The experienced and learned boyati listened to Bake’s recordings and responded with songs and stories. It was a sunny morning, there were children running around, ponds and cows and green fields beyond. Helim Boyati spoke with pride and nostalgia about a time he missed but could not go back to.

Helim Boyati listens to Bake recording of jarigan in 1932. Video by Moushumi

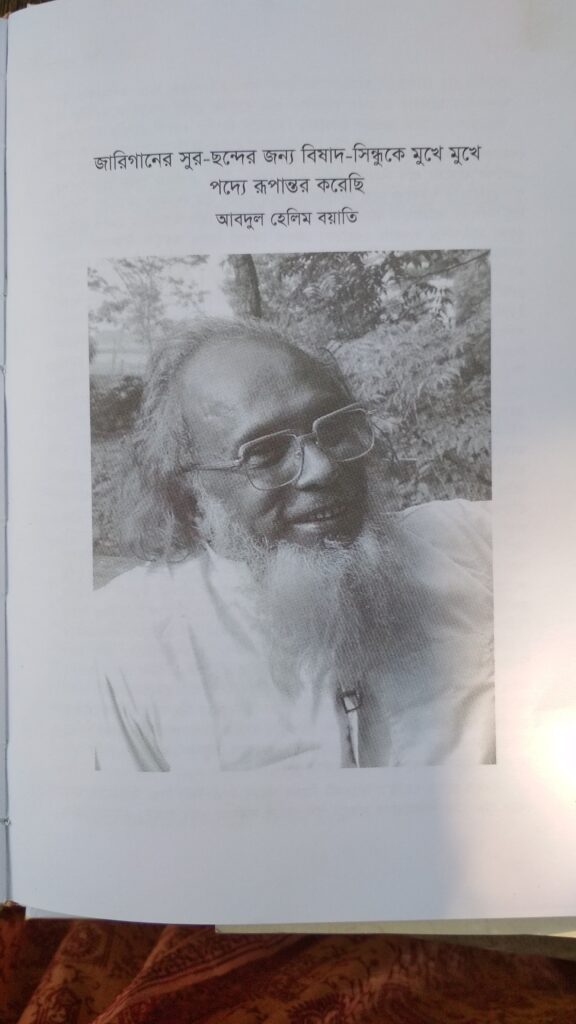

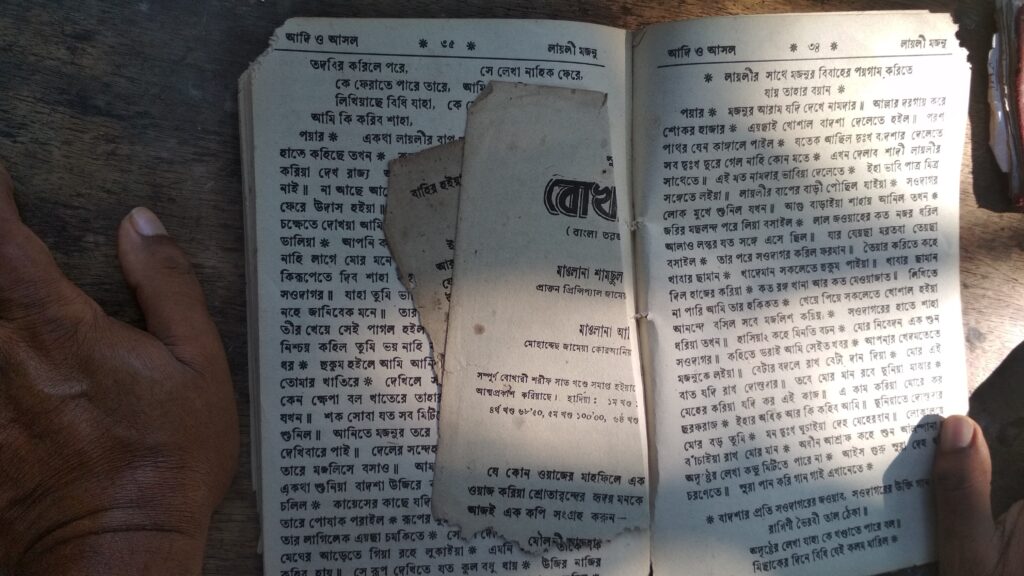

Helim Boyati also read the puthi of Layla and Majnu that day. I was not asking him about Keramat Ali, whom Doegen had recorded in the Wunsdorf POW camp in 1918. But generally about songs of this land of waterbodies. What he was saying, however, was taking me to Keramat Ali’s song. Helim Boyati also writes his own puthi. That day he told us about a puthi of Sheikh Mujibur Rahaman that he was working on.

This puthi was inside his trunk of treasures.

Jarigan and puthi-path come out of this land of rivers and beels or lakes. Here the singer is also the storyteller. Such as in Ramayan-gan, based on the Hindu epic of the Ramayan. While the tradition of puthi-path has lost its place of prominence in rural life, jarigan performances and competitions continue here, especially in the month of Muharram. On the other hand, in spite of its depleted Hindu population, the Ramayan-gan too continues to be popular in these parts of Bangladesh. The day after we went to Rajibpur, we went to the house of Shankar De, a singer of Ramayan-gan in Shatal, Kishoreganj—again part of what would have fallen within Mymensingh district during Keramat Ali’s time. In the time of Imam Bux too. Ramayan-gan is sung in these parts during shraddha (Hindu rites for the dead) observance, yet, as Shankar explained, Muslim listeners also gather, waiting for the lines about the grief of Ma Fatema, which are inserted into the story of the Ramayan.

It is Sukanta who had first met Shankar when he was working on the sound for a film on Chandrabati, the sixteenth century female poet who had written the story of the Ramayan from the perspective of Sita. Shankar works as a carpenter in Kishoreganj and lives a life of real hardship, located as he is on the margins of society, on multiple counts of class, religion and caste. Such is the story of so many powerful singers of our land that Shankar’s story is no exception. Here in this clip, he is singing the story of the twins Lab and Kush, when they meet their father Ram for the first time and tell him about their mother, Sita. ‘Who are we, King, what can we tell you about ourselves? All we can tell you is about our mother.’

This journey in search of Imam Bux and his jari, and Keramat Ali and his puthi-path, brought us in contact with many interesting singers and song-collectors of the region. Anwar, who has a music shop in Atharobari (from where Imam Bux was supposed to have journeyed to Suri in 1931-32) collects old audio tapes and videos and digitises them and then he distributes them among his customers and friends. He is a passionate local archivist.

We can end this little sub-chapter with a clip from a CD that Anwar had diigitised from what must have been a VHS tape. Here Behula has set sail in her raft to go to the heavens and ask the gods to bring her husband, killed by the angry snake goddess Manasa, back to life. The audience laps up the story, quite like how Keramat Ali’s audience might have listened to him when he was a free man and when he had not gone to war. Therein lies the continuity from Keramat Ali to Shakar De, from Imam Bux to Helim Boyati—all of them singers, sailing in the river of time.

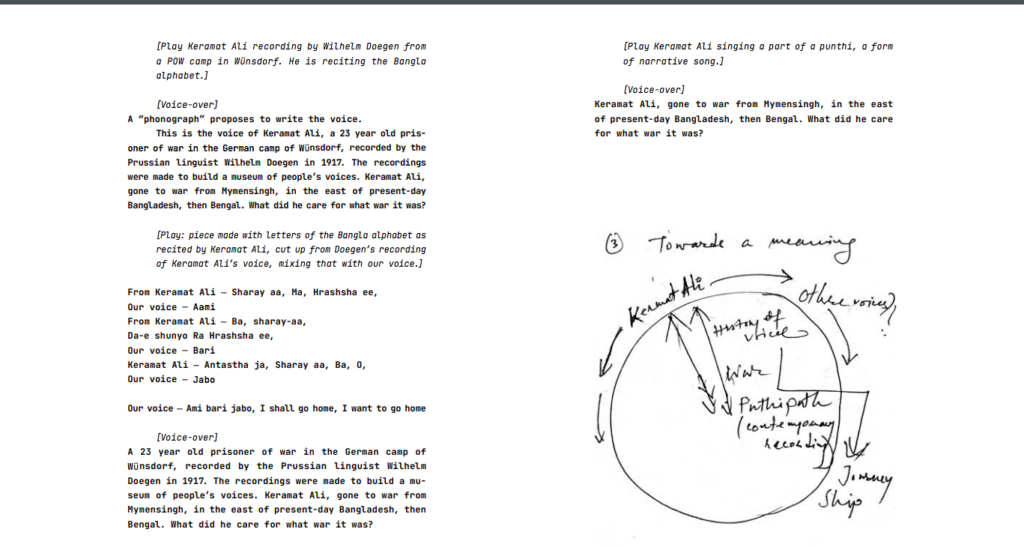

Meanwhile, there was an exhibition on the archaeology of sound, entitled A Slightly Curving Place, curated by Nida Ghouse in the House of World Cultures, Berlin in 2020 and in 2022 it travelled to Alserkal Art Foundation in Dubai. This installation was an eight-part sound play and one of the parts which The Travelling Archive had created (we made three separate parts) was on the voice of Keramat Ali. Here is a page from the book, A Slightly Curving Place: An Archaeology of Listening (Berlin: Archive Books, 2022)

Script: Moushumi Bhowmik, Score: Sukanta Majumdar