Absence and Presence

‘Every passion borders on the chaotic but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories,’ wrote Walter Benjamin in ‘Unpacking My Library’.

My first encounter with Arnold Bake’s Bengal recordings was at the British Library in 2004. It took years for this encounter to start becoming a ‘collector’s passion’. I kept meeting Bake as he was part of the road that I was walking, alone, or with fellow travellers. It was in the course of my work with his recordings that I became conscious of the fact that Bake’s sounds and images from and from around Bengal, made about ninety years before me, were my communal and personal inheritance and they held my history. As I went following his sounds, digging up my history, maps opened up for me and I got lost in them. I learned to listen to sounds, echoes and silences. This, therefore, became a story about absence and presence, about memory and forgetting.

I was in Dhaka, staying with my friends economist and political activist Anu Muhammad and geography lecturer Shilpi Barua in their eighth floor flat in Khilgaon, in January 2018. Khilgaon is a busy and noisy part of the city (where in Dhaka is it quiet anyway?). I had only just come back from a trip to Sylhet where I had met the sons of one of the sailors Arnold Bake had recorded on his ship home in 1934. It was one of my most profound experiences on this journey. On this day in Khilgaon, there were fakirs in the street below, singing and asking for alms. The honey-gatherers. The song was very beautiful and I placed my little Zoom H4n recorder in the balcony. You can hear me fumbling with the windshield, and the metal holder which can be attached to the recorder-cum-microphone. The fakirs went through the lanes and the sound moved in and out of my frame. Later when I listened, I realised there was a problem with the mic and it had added a layer of noise to the recording. Perhaps imitating the surface noise of Bake’s wax cylinders.

Arnold Bake (1899-1963), a Dutch scholar of Sanskrit and Indology and a singer, had come to Santiniketan in 1925 with his wife Cornelia Timmers or Corrie, for his doctoral research on a seventeenth century Sanskrit text of Damodara, the Sangiatadarpana (Mirror of Music), and stayed there till 1929. He was also a keen student of Rabindrasangit, taking lessons from Tagore himself but mainly from Dinendranath. He made Western Staff notations of several of Rabindranath’s songs which were later compiled into a book, Twenty-Six Songs of Rabindranath Tagore (with Philippe Stern, published in Paris in 1935). From 1931 to 1934, Arnold Bake, now on his second trip to India, once again based in Santiniketan, travelled and made recordings on wax cylinders with a phonograph loaned from the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv. He recorded songs, rhythms and mantras in and around Bengal and in other parts of India as well as in Nepal and Sri Lanka. The recordings are now digitised and archived at the British Library Sound Archive and the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin, as well as the Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology (ARCE) of the American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon. Other than Rabindrasangit, Bake also learned to sing kirtan and other folk songs and performed them too. Bake had made two more trips to India, in 1937 and then in 1956. Meanwhile, he had started to teach Indian music and Sanskrit at SOAS.

The many archives and institutions in Europe to which Arnold Bake was attached in some way or another; places where he studied and taught. Map by Purba Rudra.

From the end of 2013, I began to formally work on Arnold Bake’s recordings from and from around Bengal, made between 1931 and 1934, and then on his final trip to India in 1956. From the Bake in Bengal archive is born my own archive, marked by what Benjamin says is a ‘dialectical tension between the poles of disorder and order’.

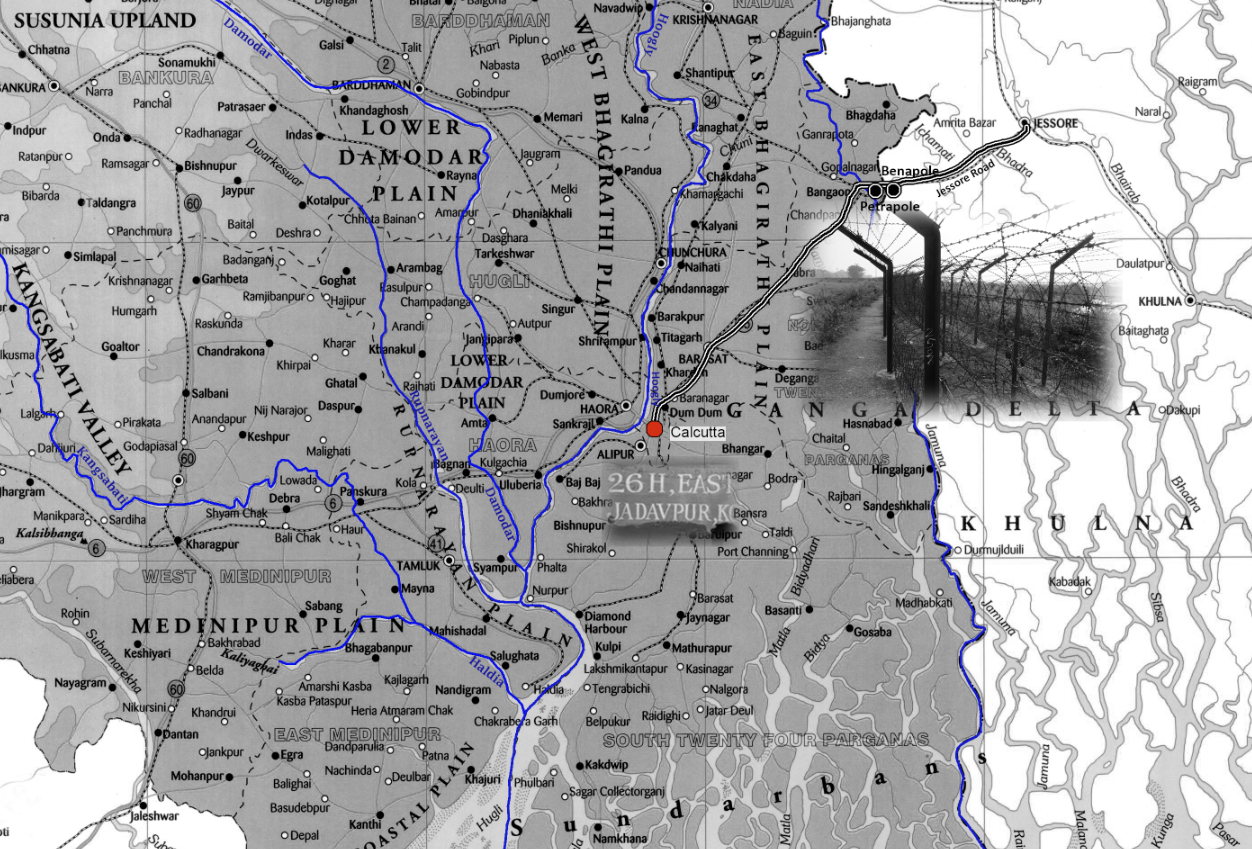

This is where all my journeys begin and where they end. My home. Map: Purba Rudra

No research is ever done by any one person, there are many who are involved in the making of this archive. Firstly, there are the sound recordists who have been part of my journey; they are individually acknowledged for each recording. Secondly, the images, still and moving, and those too are credited individually. Finally, the maps and sounds and their styling on these pages; I have been helped by countless scholars, researchers and translators, and I have tried to credit all of them in the pages which follow; if I have missed anyone, I did not mean to. My work of all these years would not be possible without the support of my institution, the School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University and the encouragement of my supervisor Professor Amlan Dasgupta. For this archive I travelled extensively and too many friends were too generous with their hospitality. I try to name them in the separate chapters and sub-chapters. Many artists have contributed songs and other recordings to this archive, and I name them separately in the specific chapters and subchapters.

Beginnings also have beginnings. As I look back, I find a funny email dating to 2007, in which the director of the Archives and Research Center for Ethnomusicology (ARCE), Dr Shubha Chaudhuri, wrote to me about an article I had written for the first issue of IFA’s ArtConnect journal. ‘I just read ur piece in Arts Connect and remembered meeting you here! Glad it all went thru and it is a lovely evocative piece of your “journey”. I hope you will consider archiving your recordings with us here at ARCE and think about making some recordings available on Smithsonian Globalsound … I would like to also add some information – that the Bake collection is at ARCE also and has been here and much used since 1982- and not available only in England. Also, the name is Arnold Bake.’ Whatever made me write Adriaan Bake instead of Arnold is something I cannot figure out now nor rectify! I don’t suppose anyone has ever called Arnold Adriaan Bake by his middle name before or after this huge faux pas! However, that surely was the beginning of something.