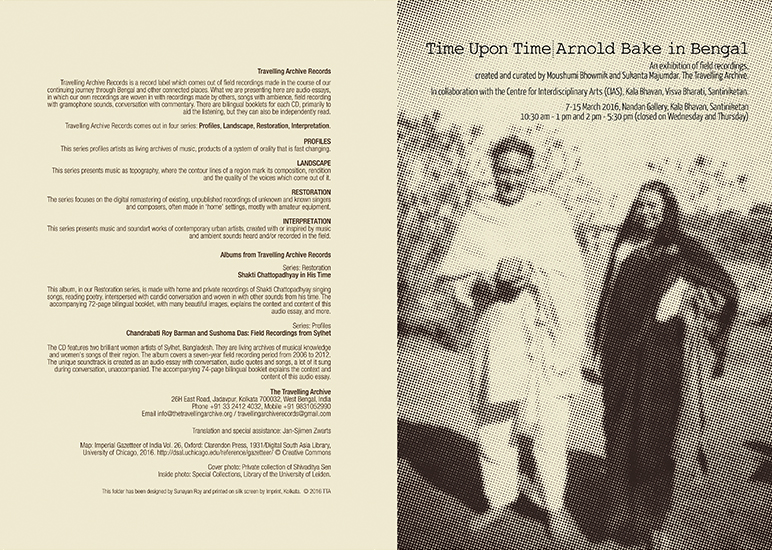

Sadhushongo

The reasons for calling this sub-chapter Sadhushongo (in the company of/learning by association with the sadhu or the wise one) are many. Firstly, it takes off from a letter Arnold Bake wrote to his old teacher and friend, the wise Kshitimohan Sen (1880-1960), in 1955. Kshitimohan had inspired a love for baulgaan in Bake (the introduction happened earlier when Tagore came to his university in Leiden). Baul is a musical and spiritual practice where ‘sadhushongo’ is a way of teaching and learning about life and living; the song is only a part of this practice. Secondly, I went with the letter to meet my own old and wise teacher, Shibaditya Sen (died 2018) , our own Shibda, grandson of Kshitimohan Sen, on 18 January 2016. The experience was joyous and illuminating. Shibda gave me some home recordings of Khoda Baksh Sai, the famous baul of Kushtia, and others.

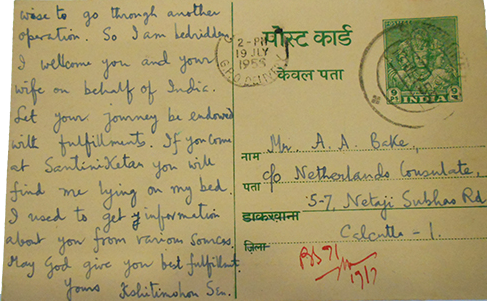

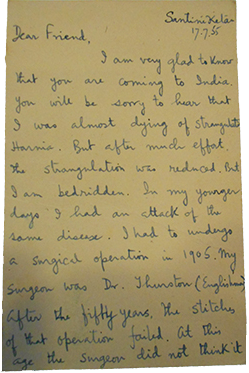

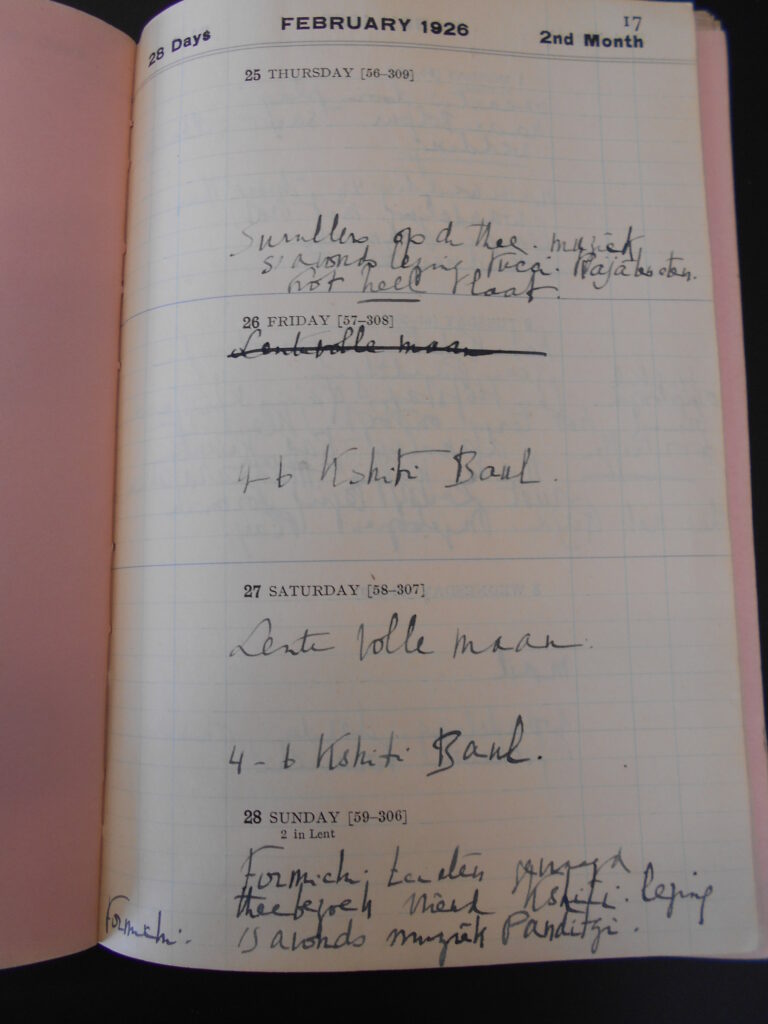

Kshitimohan Sen’s letter to Arnold Bake, 1955 and Arnold Bake’s to his mother, 1926. Photos of letters taken by Moushumi while working on a Scaliger Fellowship on the Arnold Bake Collection in the Special Collection section of the Library of the University of Leiden in 2015.

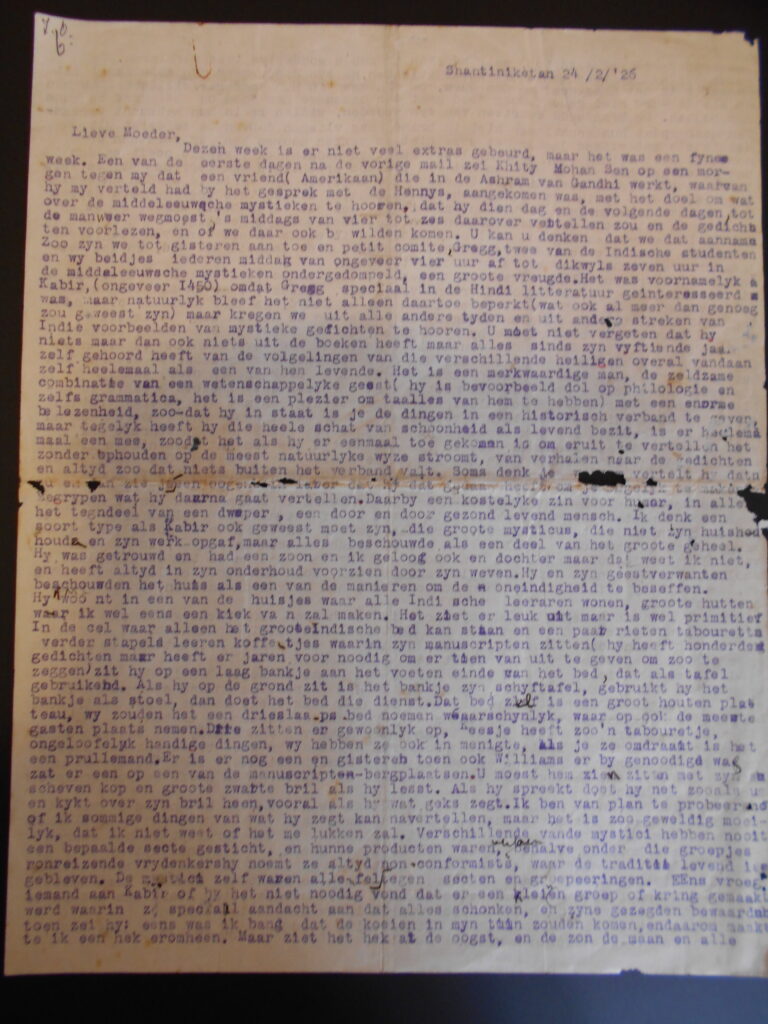

Arnold Bake was close to his teacher Kshitimohan Sen and learned much from him, especially about the bauls and the medieval saints of India during the first phase of his stay in Santiniketan between 1925 and 1929. The medieval saints of India were a major subject of discussion between Arnold Bake and Kshitimohan Sen. We know this, for example, from his letter of 24 February 1926 in which he tells his mother story after story about Kabir, Dadu (‘Dadu was actually Muslim and his real name was Dawud’, he explains), Ramananda, Ravidas, Jnanadas. Besides having more formal lessons, they go for walks together and talk. Bake attends his lectures. There are many entries in Cornelia Bake’s diaries about meetings with and lessons from Kshitimohan. In that same letter of 24 February 1926, Bake told his mother, ‘I imagine him [Kshitimohan] the kind of person Kabir must have been, the great mystic, who never gave up his household and job but regarded everything as part of the greater whole.’

Page from Cornelia Bake’s diary of 1926. Photo taken by Moushumi while working on the Arnold Bake Collection, Special Collection at the Library of the University of Leiden in 2015.

This was the background to the letter Kshitimohan Sen wrote to Bake on 17 July 1955, clearly in response to Arnold Bake’s letter to him to say they were coming to India and would be going to Santiniketan. I went with this letter and Bake’s Santiniketan photos to meet my economics teacher from my high school days in Santiniketan, Shibda.

Shibda took out photos from his own collection marked by the friendship of Kshitimohan Sen and Arnold Bake, spanning some three decades. Bake would take and give copies of photos to his friend and teacher. These photos in Shibda’s home were taken by my Dutch friend and translator, Jan-Sijmen Zwarts.

We start to see the photos and letters with Shibda. We are several of us in the room: Sukanta Majumdar (who makes the audio recordings), Jan-Sijmen Zwarts (who takes the photos), the twins Shibaditya and Shantobhanu Sen and I. Shibda used to be a major tea drinker and he also liked to share the drink with others. Throughout this evening we will hear sounds of tea-making and drinking and the clink of tea cups and spoons.

Shibda looks at the group photo of the Bakes with Kshitimohan’s family. This is Gurupally, he comments, the first rows of mud huts which were built for the gurus or teachers

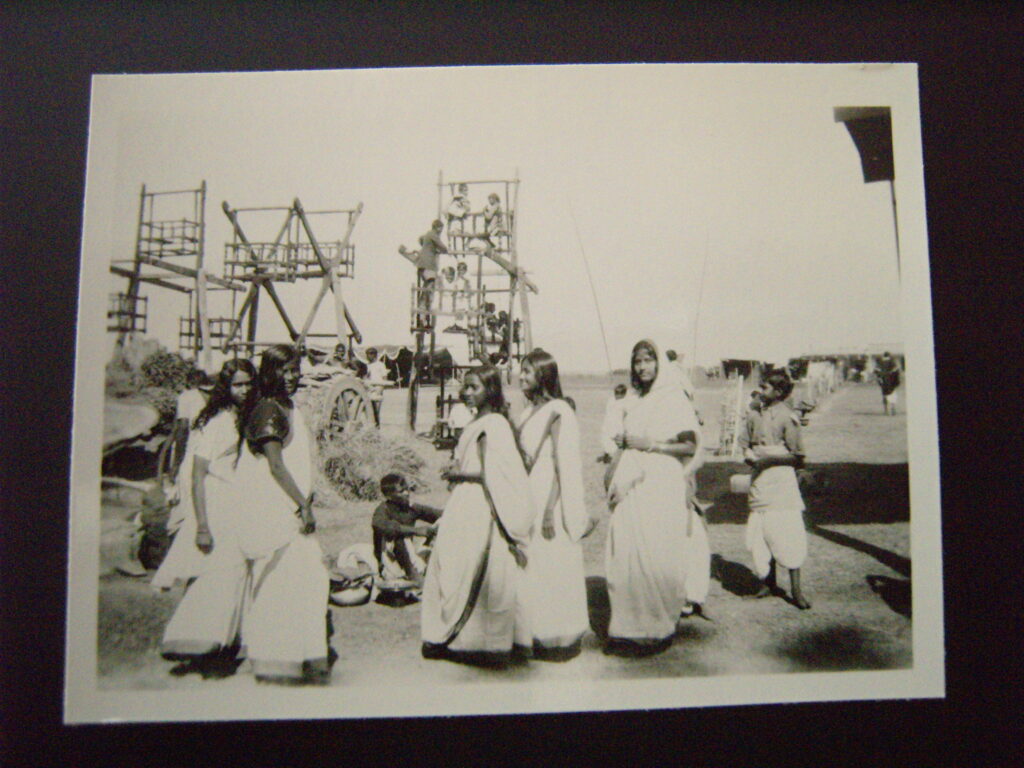

We discuss the wooden ferris wheel and talk about melas. Shibda can identify the girls in the photo, his aunt among them, possibly also Nandalal Bose’s daughter Gouri.

Photos of photos taken while seeing the Arnold Bake Collection at the Library of the University of Leiden for the first time during a visit in 2010.

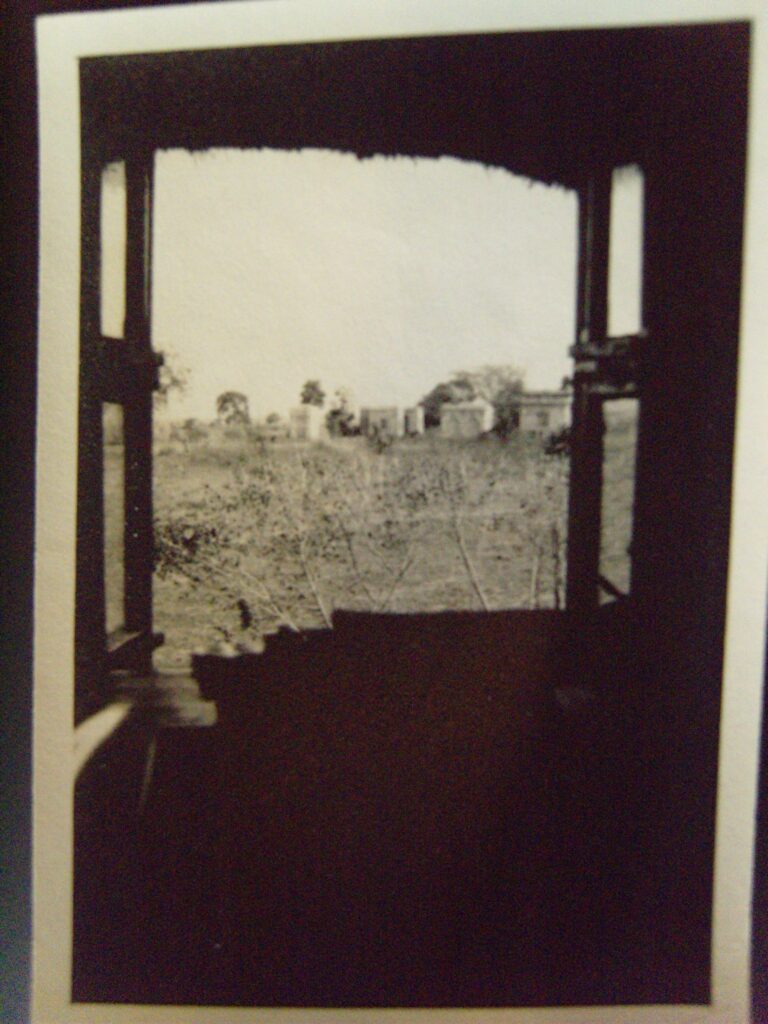

Shibda very beautifully analyses the photo of the old guest house of Visva Bharati, near the post office, where the Subarnarekha bookshop now stands. He looks at the light and speculates on the time of day when the photo was taken. Then he says, you can see how arid the landscape was in those days.

Photo of photo taken by Moushumi while working on the Arnold Bake Collection in the Special Collection section of the Library of the University of Leiden in 2015.

I ask Shibda about how Kshtimohan Sen came to Santiniketan and he tells the story of his grandfather becoming a Kabirpanthi (follower of Kabir) at a very young age in Benaras, following Tagore, who is becoming a phenomenon, working in Chamba, being called to Santiniketan by Kalimohan Ghosh. Could he sing? I ask. To which Shibda says Kshitimohan knew many bhajans, he even taught Dilip Roy and in fact the song Chakar rakho ji was taught to Dilip Roy first by Kshitimohan and then he taught it to the legendary M. S. Subalakshmi. Then he tells the interesting story of the Tagore song, ‘Baje baje ramyabina’, based on a song heard in a gurdwara. Rabindranath wanted all students and teachers to have a wide exposure to other places and cultures and so he sent them out on excursions. It wasn’t Rabindranath who had heard this song, but the teachers on such an excursion. They came back and Dinendranath sang it to Tagore but he forgot midway and then Kshitimohan sang the rest, since he had a clearer head and possibly also because he did not drink alcohol, Shibda jokes.

Baje baje Ramyabina by Sagar Sen

We read Kshtimohan’s 1955 letter to Bake. He must have dictated it to someone, because this was not his handwriting, Shibda says. We discuss that time, how ill he was, and laugh about spelling mistakes in the letter. He was 75 then, that was very old in those days. But now Amartyada is already 83, Shibda says about his cousin, the other grandson of Kshitimohan, Nobel Laureate economist Amartya Sen.

We read Annadasankar Ray’s letter to Kshitimohan, written at this same time when Bake was preparing to come to Santiniketan and planning to go to Kenduli. We discuss the route to Kenduli that they were planning to take. We know Annadasankar from Bake’s Naogaon trips

There is a mention of Mansooruddin in Annada Sankar Ray’s letter, which gets us talking about the song collector of ‘Haramoni’ fame. Mansooruddin had come to stay in their home in the early 1980s and he had stayed for about a month, Shibda recalled. He gave a talk, when he told a story about the mystic poet Lalon. A man had come to Lalon with a bag of ghunte (or sun-baked cowdung cakes which are used to light fires). He said, this is all I have and so this is what I have brought for you. Mansooruddin used this story to ask the Santiniketan alumni to give to the institution whatever they had. We also talk about another group photo in which the Bakes are with the large Kshitimohan Sen family. Shibda says, this must have been from the late 1930s. See how everyone has gained weight. And there is also Amartyada, and he was born in 1932 [1933?] and here he is some five or six years old.

About ten years have passed between the photo on the left, taken during the Bakes’ first four years in Santiniketan in the 1920s, and the one of the right from their third India trip, in the late 1930s, when they were possibly only passing through Santiniketan, because their work was elsewhere then. Photo of the 1920s photo taken by me, while working on the Arnold Bake Collection of the Special Collections at the Library of the University of Leiden in 2015. The 1930s photo was with Shibda; Bake must have given a copy to his friend Kshiti.

What was it like for a Kabirpanthi to join this university of Brahmo practitioners? I ask Shibda. He talks about his grandfather’s objective distance from the practice, even from Tagore. Kshitimohan had famously commented that it is in his songs that the poet can become himself, he can shed his beard and robe and stand utterly naked.

Shibda also tells us that it was Kshitimohan who had taught the Atharva Veda to Rabindranath.

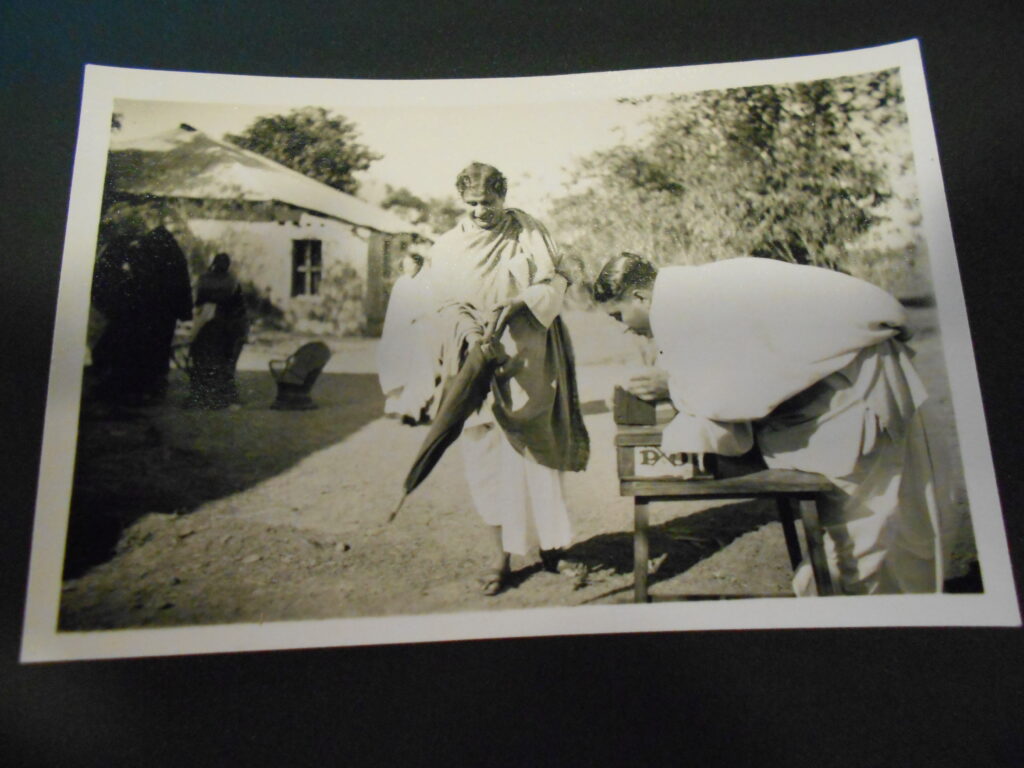

While Shibda makes tea, we look at this curious photograph and wonder what might be going on here. This was Amartya sen’s father, Kshitimohan’s youngest daughter Amita’s husband, who was trying to open a parcel come on a P&O liner. Wonder what the box contained! Photo of this photo taken by me, while working on the Arnold Bake Collection of the Special Collections at the Library of the University of Leiden in 2015.

In the course of this evening we had read a letter that Lila Ray, the American writer and wife of Annada Sankar Ray had written to Bake at this time. She was asking him to contact the song collector/field recordist Deben Bhattacharya in London about a payment to Purnadas Baul for a recording made the previous year. So, we got talking and later we played to Shibda one of the songs of Nabani Das Baul that Debenbabu had recorded in 1954. While that song ends, I ask Shibda to tell us the story of Bake’s camera and how he took the photo of his twin brother Shanto. Shibda tells us how frightened he was at the idea of being photographed and how his brother was always the brave one and how this photograph was kind of staged—there was a pot with grains and the idea was that Shanto should pretend to feed the birds and Bake would take a photo.

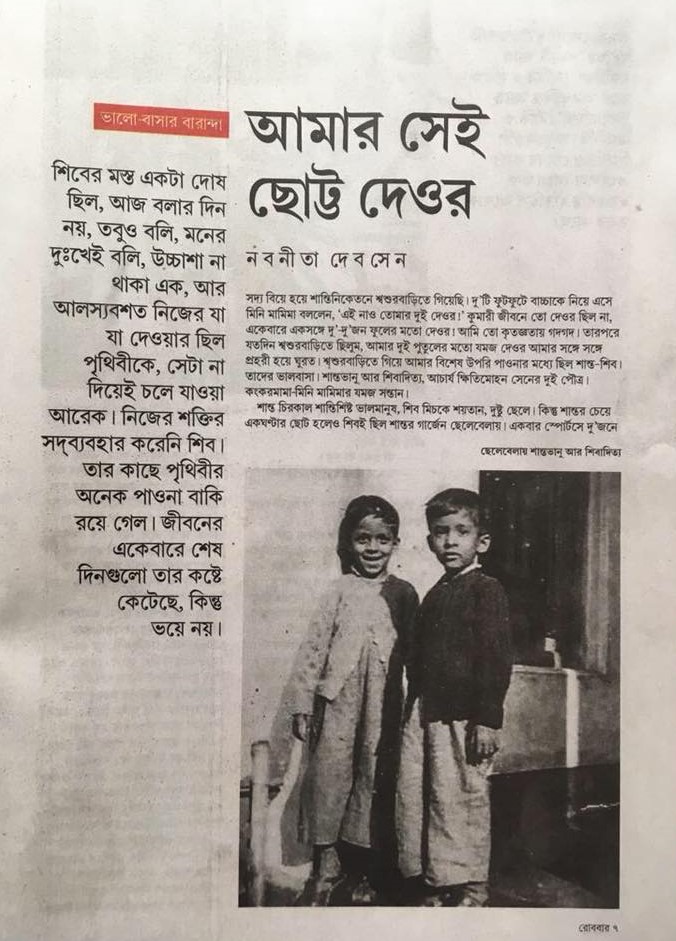

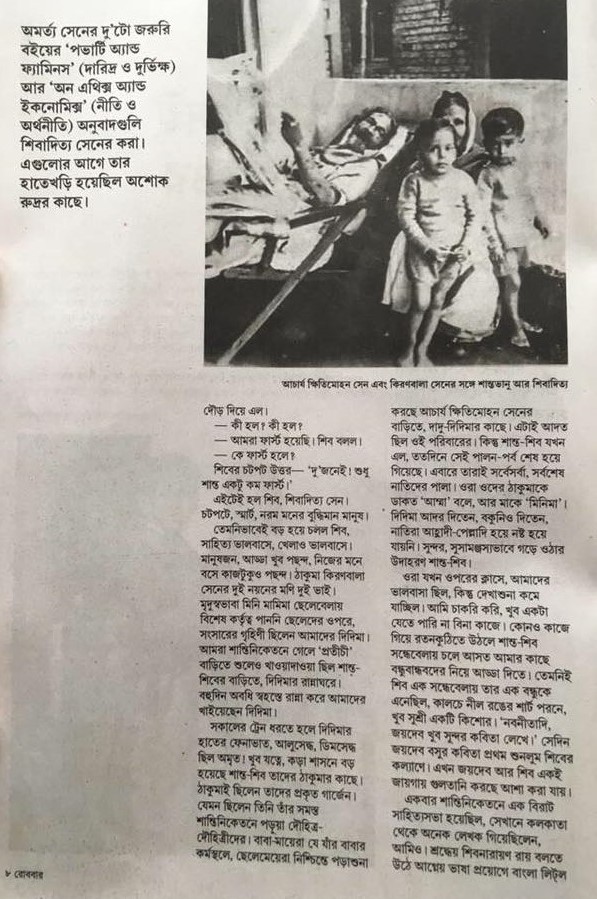

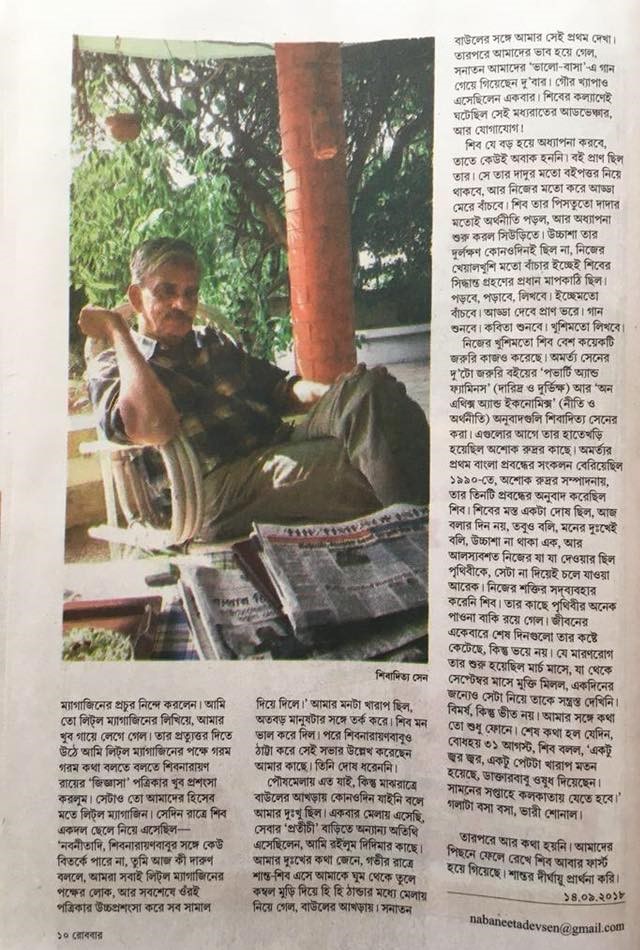

A tribute the writer Nabaneeta Dev Sen wrote to Shibaditya Sen, who used to be her cousin, in Robbar, the Sunday magazine of Sanbad Protidin, on 14 September 2018.

Shibda gave us scans of some photos from his collection, one of which we put on the cover of our folder for our Time Upon Time exhibition.

Arnold Bake might have given this photo to his friend Kshitimohan Sen as a memento when he stayed in Santiniketan, or maybe he sent it with a letter from home?

Shibda told us about things going wrong in Visva Bharati towards the end of Tagore’s life, coteries forming, unholy cliques, which made many of the scholars leave. Kshitimohan had been offered a job in Calcutta University and then Tagore apparently said to him, even you will leave me? Kshitimohan stayed on.

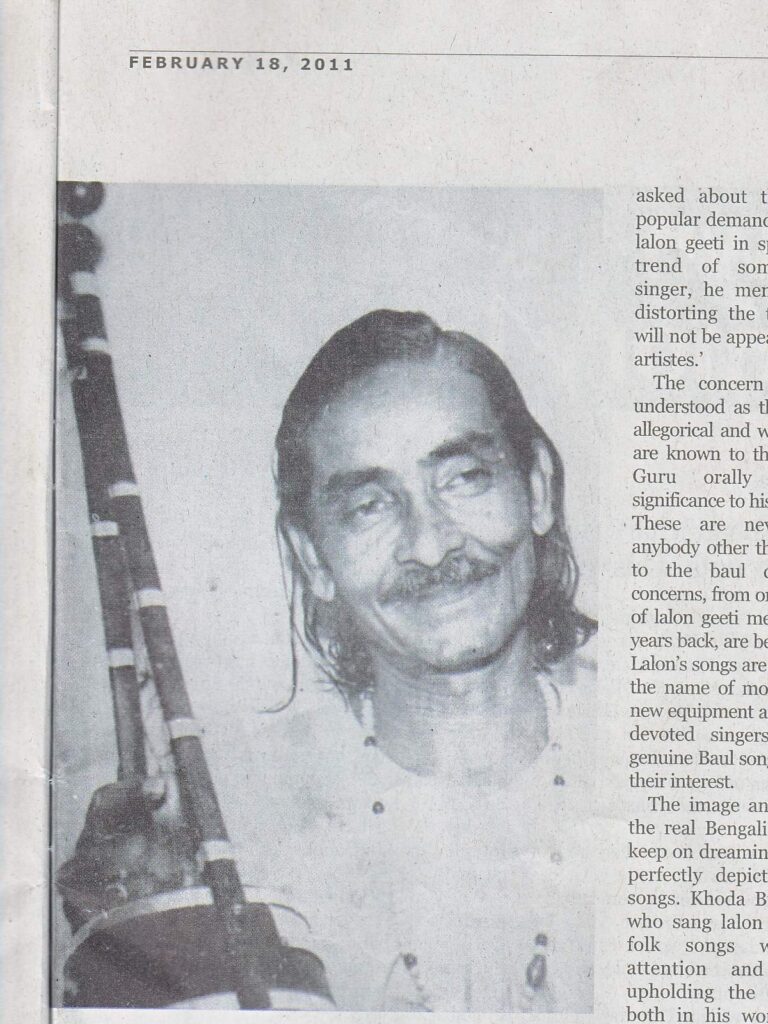

Santiniketan celebrated the centenary of Kshitimohan Sen by inviting some renowned bauls of Kushtia to perform in 1980, including Khoda Baksh Sai or Khoda Baksh Biswas. The baul scholar Carol Salomon (killed in a road accident in 2009) had recorded the aashor at Santiniketan. Here the scholar-performer Sudipto Chatterjee writes beautifully about her, which gives an essence of not only her work but also of the world of sound she adopted as her own for most of her rich, though abruptly-ended, creative life, full of erudition, inquiry and humility.

Song received from Soumya Chakravarti and uploaded with permission from Richard Salomon

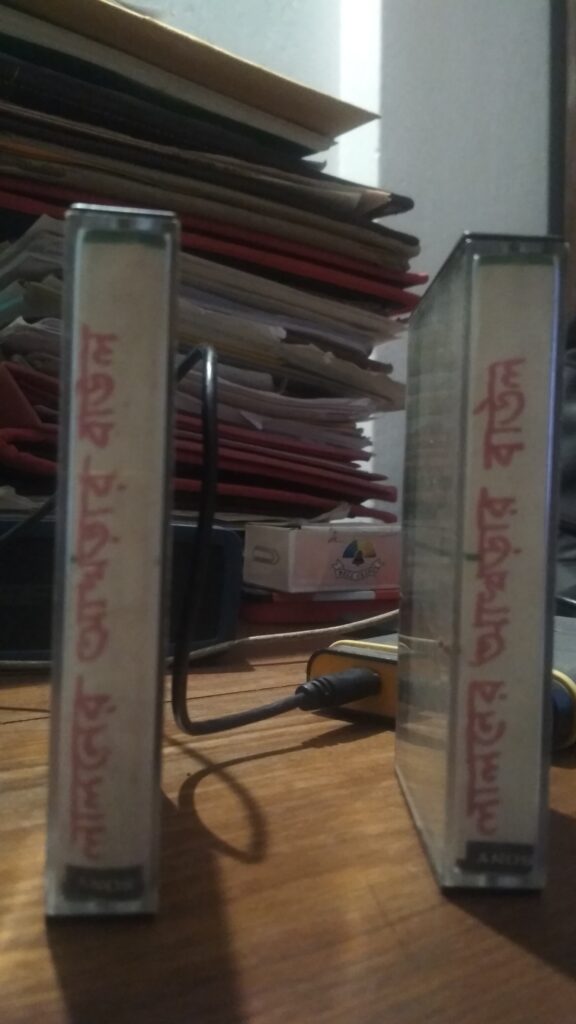

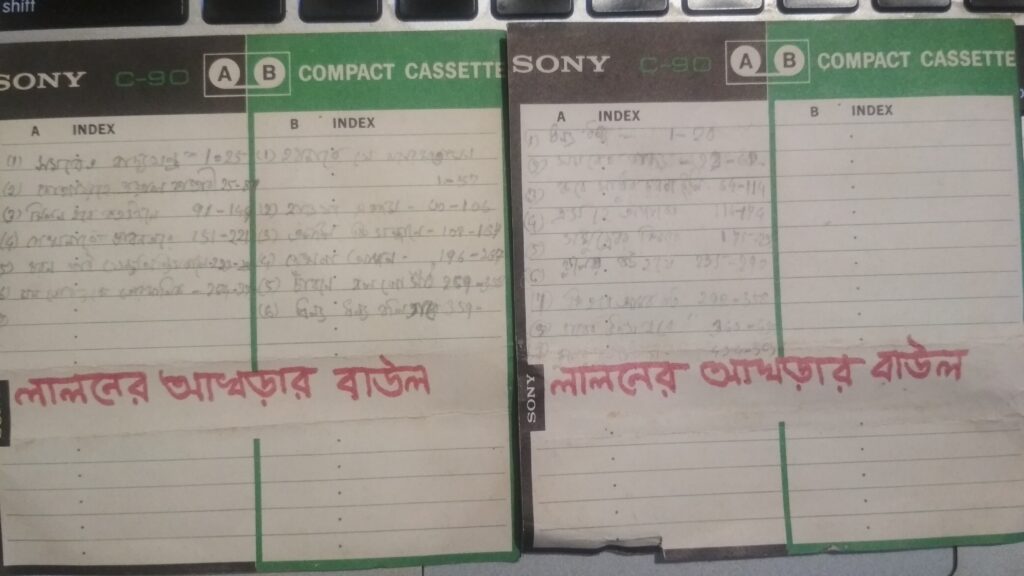

Shibda had given me two audio cassettes of songs from a private music session recorded perhaps in Santiniketan during this same trip. They had songs of Khoda Baksh Sai.

Cassette1 – SideA

Cassette1 – SideB

Cassette2 – SideA

Cassette2 – SideB

Cassettes digitised by Arijit Mitra

This sub-chapter is becoming like a bandanagaan, the song of gratitude towards the elders, ancestors and gurus—those who give us life and teach how to live; also, to our patrons. We usually start a concert with such a song. But here I am putting the final brush strokes to my archive born out of the Arnold Bake in Bengal archives. In some cultures, people sing the praise of the earth and the sky and rivers, lakes, hills and dales, and all living and non-living things, ancestors and children, those who came before us and those yet to come. In other cultures, every time we take a meal we say thank you for the food we are about to eat, for food and shelter are a blessing for which we must be grateful.

In this piece I have tried to say thank you to those who gave me the song.

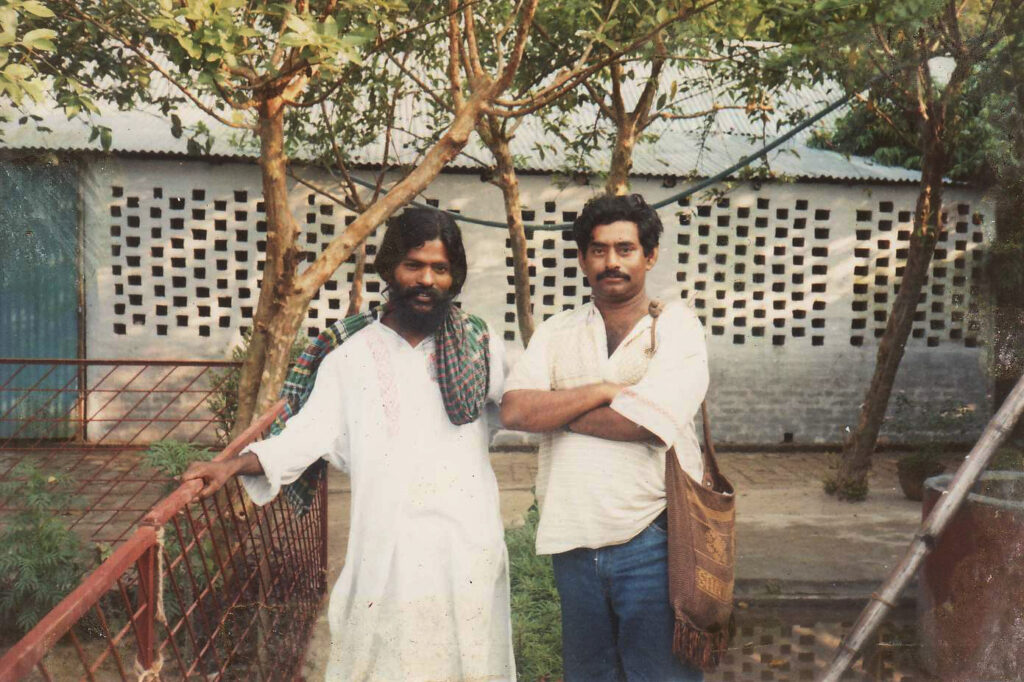

Our longtime friends from the Faridpur-Kushtia-Joshor world of bauls and fokirs, Nazrul Fokir and Salamot Khan, in Faridpur 2014. Photo: The Travelling Archive

Interestingly, in 2014, before formally taking a plunge into Arnold Bake’s world, I was in Faridpur with old friends, listening to songs of the bauls of Kushtia. Salamot Khan, about whom I so often write and whom I have seen as my teacher and friend and so much more—an irreplaceable archive of local knowledge; very wise as well as who had a rare gift of wit, was at the centre of that evening’s discourse. There was also Milonbhai (Mahfuzul Alam) and another longtime friend Sanjay Sikdar. Sukanta Majumdar was there and we had asked Nazrul Fokir of Kushtia to join us and the meeting would take place at the house of Milonbhai and Lona.

Salamot Khan in Faridpur, 14 August 2014.

The exchange between Salamotbhai, Nazrul, and Milonbhai was at the level of high art that evening. This was essentially Sadhushongo. The music they were weaving into the conversation was just sublime! They sang verses of the folk poets of their Kushtia, Faridpur and Joshor region, especially of Lalon Fokir, Behal Shah, Khoda Baksh Sai; they were talking about the congregation of saints, of melas, of the love and devotion of the bhakto or devotee. They were talking as poets do, in riddles. I was a mere outsider-listener.

As I am listening now, what amazes me now is how several of the themes discussed that day showed up in my later work. For example, they keep going back to the songs of Khoda Baksh Shai and talk about the kind of natural poet that he was, chaaron kobi they say, suggesting a kind of recordist or chronicler, who could make up songs in the spur of the moment. They discuss his portrait by ‘a Poona photographer’, captioned ‘Rasik’: ‘This was taken when they went to Santiniketan, right?’ They are not absolutely sure about the photo’s provenance.

So, this image of Khoda Baksh is possibly from the same time when the tape from the aashor was recorded during the Kshtitimohan Sen centenary. Image courtesy Milonbhai.

Nazrul Fokir sings a song of Khoda Baksh Sai and Salamotbhai explains the physiognomic reasons for the unleashing of ras (rawsh) and bhab.

Milonbhai and Salamotbhai have engaged in sadhusongo all through their lives. Here Milonbhai is seen with the Lalon singer Rob Fokir of Chheuria.

Mahfuzul Alom Milon sings Khoda Baksh Sai’s song about Benarasi Sadhu, an ascetic who sat in his shrine in Satdua, smoked ganja all day long and devotees and wise men and women gathered around him and the atmosphere became truly transcendental. Yet, despite the ganja, mela and congregations of the great wise poets of this land, the song Milonbhai sang was also about killings of devotees in the shrine in 1971.

That evening of 14 August 2014, there was not only music that filled the air, but the ‘sadhus’ gathered talked about a lost past, a time of real and beautiful sharing between the Hindu and the Muslim, between believers and people of diverse faiths—something which is becoming increasingly hard to conceive today.

Nazrul Fokir sings a song of Behal Shah and Salamotbhai explains how he is actually singing the Surah Fatiha in Bangla.

Finally, Salamotbhai sang a song of Khoda Baksh Sai, ‘Tumi chhile ektara hole ektara’

There is a way of singing in Kushtia, a direct approach to the note, almost as if there is no place for the meend/meer or the gliding note, apparently unsentimental. Yet, I have met some of the most emotionally sensitive people in these places. I want to end this piece with an image of Nazrul. I was coming home from a field trip in 2018 and passing through Poradoho station. The place is not far from Kushtia. I was in a moving train and Nazrul Fokir came to the platform to meet me. This image is just how Nazrul’s songs are. Deep and inwardly bending; Salamotbhai used to say the life of a fokir or sadhu cannot be easy. The pain is part of their process.