Archives: Record Session

On 29 October 2018, I was at the British Library sitting at the desk of Lead Curator of World and Traditional Music, Dr Janet Topp-Fargion, looking at some papers relating to Arnold Bake, the Dutch scholar of Sanskrit and Indian music, pioneer field recordist in the Indian Subcontinent in the 1930s and 40s, for my ongoing research on his wax cylinders from Bengal. They gave me a few files with miscellaneous papers and after I finished going through what I had gone to study, namely the typed up sheets of the first catalogue notes for the cylinders, I continued to browse through the other papers, for they looked interesting enough to me. I was allowed to take photos of the papers with my phone and occasionally I found something to bring back with me. Then, I found a few typed sheets stuck together with a pin, with the heading: ‘Overseas Research Leave, Report by Dr A. A. Bake, Reader in Sanskrit. India and Nepal– May 1955 to August 1956.’ This was Arnold Bake’s last trip to India (and Nepal). I was curious, as I knew of two recordings of Tagore songs that he had made in this time, one of Indira Devi Chaudhurani in Santiniketan and another of the Tagore singer Chitralekha Chowdhury, then a young schoolgirl who studied at Patha Bhavan, and whose mother was the painter Chitranibha Chowdhury. We had in fact interviewed Supriyo Tagore, Indira Devi’s nephew and Chitralekha herself for our exhibition Time Upon Time, playing them the songs and recording their listening. Bake’s notes about his recordings are always scant, so throughout my work I have had to look at other sources for more information, such as his letters. I wondered if there was something in this report about his Bengal recordings from that trip.

Purnadas and his son Dibyendu Das, Kolkata, Sep, 2019

‘The outward journey by Clan Macintosh, from Liverpool to Calcutta was extremely comfortable and pleasant. A dock-strike in Liverpool threatened to cause considerable delay, but…’

I went skimming through the pages. He arrives in Calcutta via Colombo, goes on to Nepal, then goes to Delhi, then Benaras, comes properly to Calcutta. Eight months have passed since he had embarked on this journey. ‘Arriving in Calcutta on the 24th February we just escaped being stranded in the general–and complete–strike on that day. Zero hour was 6 a.m. and our train arrived at 5.30 a.m., which made it just possible to catch one of the last taxis running, to reach the boarding house before everything came to a standstill. My wife and myself, the driver and an assistant and 26 pieces of luggage (including my recording equipment) in one single not too large taxicab. The hartal had been organised as a protest to the proposed merger of Bihar and Bengal to one administrative unit (as it had been up to 1912 or thereabouts), and was only one of the manifestations of popular –or political–dissatisfaction with the decrees from Delhi. On the whole, things went without loss of life, except for a couple of poor shopkeepers, who thought that, as on previous occasions, the hartal would be over at 4 p.m. instead of at 6 p.m. as decreed and who were promptly stabbed to death.

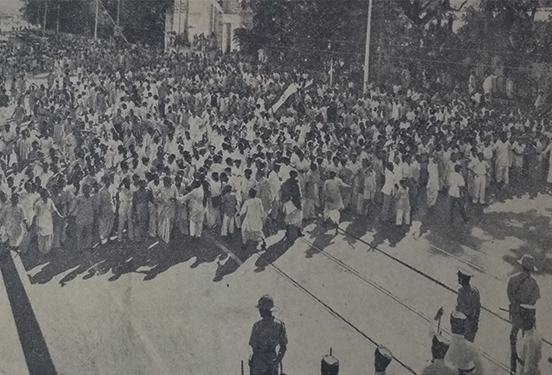

From local newspapers, photos of satyagrahis protesting the merger of Bihar and Bengal

‘As luck would have it, there was a festival of Bengali folk music shortly after we arrived and I was able to take several records of Vaishnava religious songs as sung by groups of wandering mendicants from West Bengal. Kindness and helpfulness from old and new friends were most enjoyable and made the days unforgettable. The same was the case during our visit to the Santiniketan after an interval of nearly 20 years. Also there I had the opportunity to make some interesting records of Oriya songs and folk music and Bengali songs, including the rendering of one of Tagore’s songs by his niece, aged 82–the acting Vice-Cancellor of Visvabharati University–a remarkable achievement on the part of the old lady.

‘On our return to Calcutta, I had hoped to acquaint myself with the stock of recordings anthropologists of the Indian Museum had made in the field, but an unexpected setback in health…’

I knew the song of Tagore’s niece of course, many know it; it seems that Indira Devi used to like to sing this song, ‘Katobaro bhebechhilo’, during this time (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K9bb9dumEM4). But what is his Bengali folk music festival he is talking about? Where are the recordings he says he made there? I asked Janet and she in turn asked their Bake-in-Bengal researcher, Christian Poske. He brought out two audio files marked C52/NEP/67 and C52/NEP/68. C52 is the Bake Collection at the British Library’s Sound and Audiovidual Archives. NEP would mean his Nepal recordings. By now Bake is no longer making recordings with the phonograph, on wax cylinders (1931-34), nor on the Teficord sound recorder, which he had used in the second phase of his field recording trips, from 1938. He was using a reel-to-reel recorder now. Bengali folk music recorded in Calcutta marked Nepal, with no other detail except to say Vaishnava songs. It is not surprising that after years of browsing the catalogue, and listening to Bake’s recordings, I had never found these.

Janet offered to open the files for me on her computer, so that I could listen. These were far longer sessions than anything we have had from Bengal so far; a wax cylinder could record for only about three minutes. These two tracks were of about 16 minutes each. I sat down to listen. The moment the first track, C52/NEP/67 started to play, I knew I had struck gold. I also knew I had no way to take these recordings back with me, no way to take them to people who would know and identify the singers, so I would have to listen as closely as I could and then use those those sonic impressions to find my way.

Here is the note I typed on my computer:

29.2.1956 and 1.3.1956—banga sanskriti sammelan?

Calcutta

C52/NEP/67 16:34 track

Religious Vaisnava songs, sung by the mendicants

Jiban he nutan, nyay na jeno chore, dekho dekho mon—Sanatan?/Nabanidas? (Nilakantha) khamak ghungur kartal

Gurupade prembhakti holo na mon hobar kale—fakiri style—prasanna kumar

Gurupade prembhakti again

C52/NEP/68 15:11 track

Sonar manush eshechhe bhai dekhbi jodi aay/ogo tribhuban korechhe alo jhalok daey bidyuter gaay—same singer– dugi, ektara aar kortal (performing, can hear reverb) বয়স্ক

Kal shokale hori bole amay nitai probhu tene naey (female singer) –khanjani prochondo echo , khola space e gaan mone hoy. Dotara accompaniment—manju? / purno sister? Sounds like a young voice.

Purnodas surely—ore amar abodh mon /sarbada chetane thak re mon

Banka nodir gotik bojha bhar—adbhut ektana fakiri style

Ektara dugi, ghungur

I had to tell Janet after I finished listening, that this was no ordinary recording, but I refrained from saying anything more. I asked if they would upload the recordings along with their other Bake-in-Bengal tracks (https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Arnold-Adriaan-Bake-South-Asian-Music-Collection), they said they could not do that just now. I was excited and worried too. I felt like I was holding something very precious in my hands and I knew I would have too take extra care of it. Such knowledge is, in fact, very fragile; a momentary lapse and it can break.

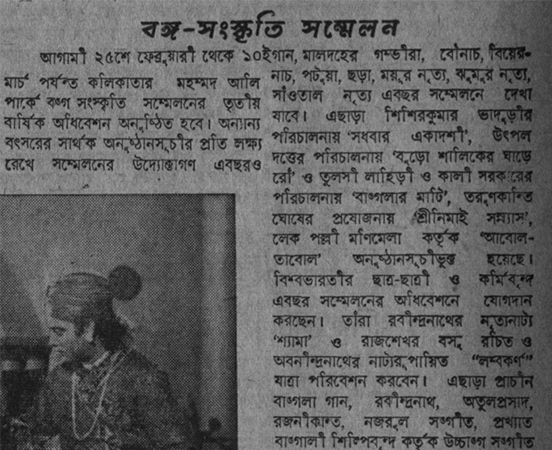

The following months, back in Kolkata, I had to think of ways by which I could establish the provenance of those two tracks. Where could I start working with a sound, which I did not have with me and which lay silent in the vaults of an archive many seas away? Dates, I thought. 29 February and 1 March 1956. What was the festival that Bake was talking about? Could it be the Banga Sanskriti Sammelan. A young friend, something of a bibliophile, Apurba Roy, and I tarted to search through old newspapers. 1956 was a leap year and indeed, the Banga Sankriti Sammelan had opened on 25 February that year. We found photos in the papers, the pandal at Muhammad Ali Park had caught fire the afternoon before the festival was to begin, but organisers promised to start at the same venue on the fixed date. The doyen of Bangla stage Sisir Kumar Bhaduri would open the festival. Historian Nihar Ranjan Roy would speak. The whose-who of Bengali literary and cultural world would descend on the pavilion, from classical to art song, theatre and folk performances too. Kalipada Pathak, Indubala, Angurbala, a troupe from Santiniketan, Nirmalendu Chowdhury, Sheikh Gomani Dewan… We searched programme announcements for names of the baul singers, and went through reviews to find something about who had performed. There was nothing. No name of any of the singers who I thought I had heard in the recordings at the British Library.

News of festival fire and review

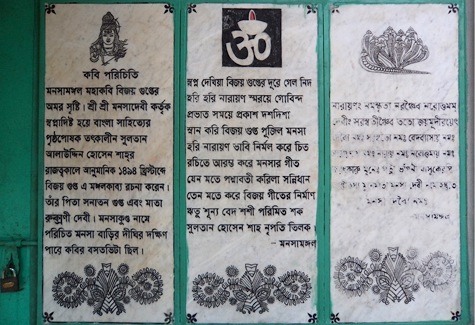

So I decided to meet Purno Das Baul and ask him if he remembered performing at the festival in 1956; if his father was there and who else might have been with them. If Arnold Aadrian Bake had recorded Nabani Das Khepa Baul in 1956, then it was history. Nabani Das Khepa Baul (1890-1964), who shines in a galaxy made up of such stars as Rabindranath, Kshiti Mohan Sen, Shambhu Saha, Shantideb Ghosh, Mukul Dey, Deben Bhattacharya, Richard Lannoy…

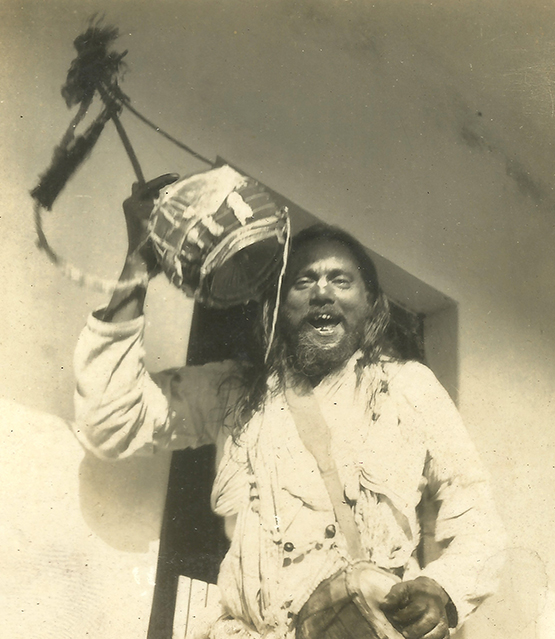

Richard Lannoy photo of Nabani

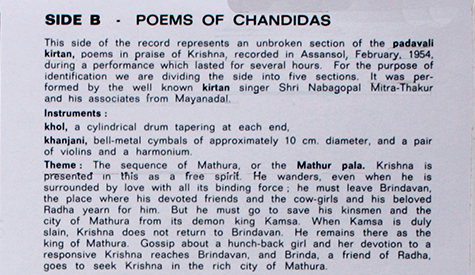

We know about the first and only recording of Nabani Das Baul and the first of Purno Das and Lakshman Das, made by Deben Bhattacharya, at the Banga Sankriti Sammelan of 1954. Debenbabu has talked and written about it. There are enough publications from that trip to stamp it with lac. After all, Debenbabu was the kind of recordist who made sure he carried his recordings out into the world. In one his last and final conversations with the actor and theatre director Aly Zaker in Dhaka in 2001, he had talked about that trip and about the festival, about how he had come with his photographer friend Richard Lannoy, how he had recorded Abbasuddin and Nabani Das Baul, how he had gone back with cans and cans of songs and tunes, enough to compile many albums. We have heard from Deben Bhattacharya’s wife, Jharna Bose Bhattacharya, stories about Deben and Richard’s trip to Nabani Das Baul’s home in Suri. All of this is known history now and the two songs of Nabani Das Baul, the only recordings of his voice so far heard, are available, even on the internet.

Listen to a Nabani Das song recorded by Deben Bhattacharya in 1954, Gour chander haspatale

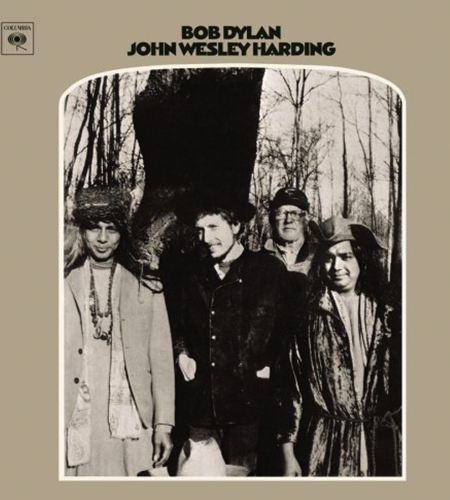

The Purno Das and Lakshman Das recordings of Deben are another story. How they played a role in opening the doors to a whole wide world for the bauls. How they carried a sound to the West which also led to the making of a sound. That should be the subject of another session note.

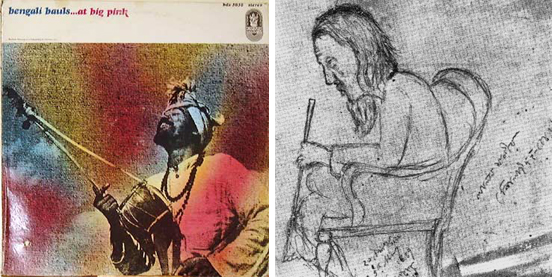

Cover of Bengali Bauls at Big Pink, released by Budda in 1968 (left). The image they used was Sambhu Saha’s portrait of Nabani Das Baul taken some time after 1937. This image is as iconic to baul matters as Jyotirindranath’s sketch of Lalon Fokir from 1889 (right).

I met Purno Das Baul and his son Dibyendu (Chhoton) in their home in Dhakuria, south Kolkata, on 7 May 2019 . The 86-year-old Purno Das remembered the Banga Sanskriti Sammelan, although he got some details of the fire mixed up. He insisted the venue had been shifted after the fire, which was not the case. Never mind that. As I read out from my notes, and told him what I had found out from the papers, he began to talk about his father’s songs, their musical family, his own musical journey, the fire in the tent during that year’s festival, and much more. This is how we have organised the recording from that day.

00:00 Chapter 1: Talking about the 1956 recording

15:40 Chapter 2: On Nabanidas Khepa

21:30 Chapter 3: More songs. First trip abroad, to Russia. Did not know anything about the value of archiving. Hence, so much has been lost.

25:56 Chapter 4: American trip in 1967, following Allen Ginsberg’s visit to their home and later of Sally [and Albert Grossman, of Woodstock fame]. Other singers in their group were Purna’s brother Luxman Das Baul, Ashok Fakir and Sudhananda Das.

27:46 Chapter 5: Family, lineage

32:51 Chapter 6: More on Nabanidas

33:34 Chapter 7: About Edward C. Dimock and Charles Capwell

34:15 Chapter 8: Voice of Purno Das’ mother Brajabala (Nabanidas’ wife)

40:16 Chapter 9: About photos, Sambhu Saha, Sai Baba

43:50 Chapter 10: The historical importance Purno Das Baul and his early recordings

We then decided that Purno Das would write a letter to the British Library and tell them about what he had heard from me and about how he was convinced the recordings were of his father and their own songs. And how they would like to have a copy of the recordings.

The rest does not need elaboration. The letter was taken, the plea heard, the recording repatriated by the British Library. A happy ending for all.

What we have here are a set of recordings from a session when we listened together to the recordings the British Library had sent to Purno Das Baul. We cannot play here the archival recordings as we do not have the permission to do so. Here is a recording of our listening to the recording. Such as the photos of photos we take, and bring back with us, this is a recording of a recording of a recording–many times removed from the source, but a source in itself.

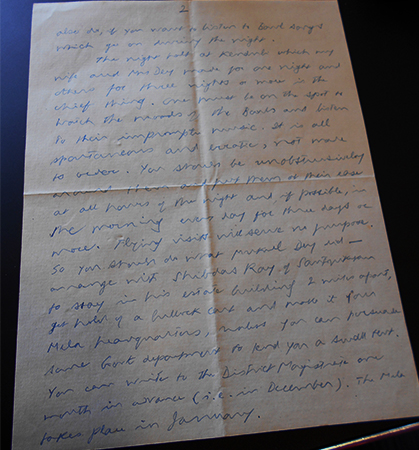

Strange streams meet in this story. The Santiniketan world of which Nabani Das Baul was a part was also a world which formed Arnold Bake. He went there as a 26-year-old young researcher in 1925, and his love of Indian music, songs of Rabindranath, folk music, the bauls, kirtan–so much came out of his years of association with the place and deep friendships he forged there. Not only because of Santiniketan, but surely that time in his life played a huge role in the choices he made. Which is why, before coming on this 1955-56 trip, he was writing to his old friend Annada Sankar Ray and making plans about what they might do, how they can listen to baul songs, how they might go to Kenduli. And Roy suggests that he consult Mrs Mukul Dey about this, as they have recently gone to the Kenduli mela. Interestingly, there are among the private papers of Mukul and Bina Dey (http://www.chitralekha.org/) evidence of the fact that Bina [Mrs Mukul] Dey would visit Nabani Das’ akhra. She wrote down directions to the place as well as words of songs in her notebook. This same Bina was also a friend of Mrs Bake’s, for they had met in their youth on the grounds of Santiniketan. Here s a photo of a photo of a photo–something from the library of the University of Leiden, where Bake was a student and where many of his papers are housed.

Photo from the library of Leiden University

Annada Sankar Ray letter

The fact of Arnold Bake’s non-recognition of Nabani Das Baul, or at least the fact that Nabani remained unmentioned in Bake’s notes, troubles the mind. We speculate on answers. What is an archive? What do we keep in an archive? What do we fail to keep? What happens to the unrecorded part of the story? Is it lost forever, or does it remain in some other form, as another kind of trace?

At The Travelling Archive, we are often faced with this question. We fail to keep records too. We fill in for the gaps left by people before us, someone else will fill is our own gaps. That is how life flows and knowledge grows. What is wonderful is that we have two new songs of Nabani Das Baul, a song of Sudhananda Das Baul (who came from a tradition of kobigan singing in East Bengal and hence had such a distinctive style), a song of the gentle Radharani Dasi, Purno’s sister who loved him so much that she refused to record for HMV when her brother was not offered a contract, the brilliant Purno Das Baul in his late teens, and his brother-in-law, Gopal Das, who was a yogi and travelled about, singing songs. ‘Perhaps Radharani would accompany him if she did not have to care for her infant nephew,’ wrote Charles Capwell in his book Sailing on the Sea of Love. ‘She and Gopal have no children of their own because, as Laksman explains, they are yogis; that is, they are adept at baul sadhona… Radharani likes to sing and does so well; nevertheless she does not get as much opportunity to sing as she would like because most of the attention is given to men.’ Perhaps Radharani longed for her own child too, like she longed to sing? How to know? Where do we find the record of such things?

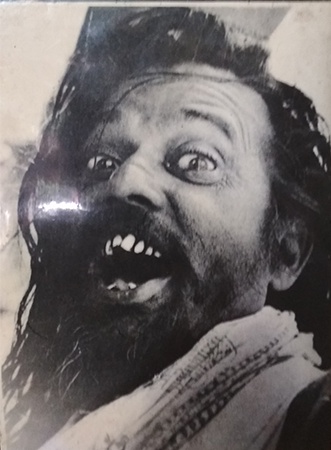

We will end this session note with two beautiful photos by a woman artist from Santiniketan, Kiron Barua, who was born in 1924 and studied at Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan. She captured the madness of Nabani Das Baul, the khepa baul, with her Rolleicord camera, some time in the 1950s. This is how we can assume Nabani Das Baul to have looked on stage when Bake was watching her perform.

Written by Moushumi Bhowmik and page designed by Sukanta Majumdar, Aug, 2020

Related link:

https://www.anandabazar.com/supplementary/rabibashoriyo/story-of-nabani-das-baul-father-of-purna-das-baul-article-by-moushumi-bhowmik-1.1193096 (accessed in Aug, 2020)

It is strange to write a session note more than a decade after a field recording trip, to recall details of an experience of 2009 in 2020. Now, it is the recording that has to take us back to that day, also the photos and recordings from days before and after the session. That is all we have with us, there aren’t any other field notes, as I am not in the habit of keeping a diary. This in fact is the diary we keep. We also have our individual and collective memories, and we tap into those.

I am trying to remember if there was a specific reason for us to go to meet Lakshman Das Baul (also written as Luxman and Laksman in various sleeve-notes and books, sometimes also enhanced with diacritics, while we pronounce the name more as Lokkhon), in his home in Suri on 18 November 2009. We were four of us; besides Sukanta and me, there was our friend, musician Satyaki Banerjee and Biplab Ghosh, a poet. We went in the evening, it was about 7 pm when these recordings were made. Before going to him, we went to meet Abani Biswas of Milon Mela, The Sources’ Research theatre project (https://digilander.libero.it/milonmela/), built on the ideas of Jerzy Grotowski’s Theatre of Sources. And, before going to Abani, we had gone in the morning to meet Gour Khepa (the Gour Khepa session notes and recordings can be accessed here https://www.thetravellingarchive.org/record-session/bolpur-birbhum-18-november-2009-gour-khepa/).

So, I try to go backwards, looking for the ‘source’.

In 2009, several years into our field recording, our own folk festival in Shaktigarh, Jadavpur, the Baul Fakir Utsav having quickly grown from seed to quite a big tree in the past four years while we were preparing for its fifth edition in January 2010, with Deepak Majumdar, Georges Luneau and Ruchir Joshi in circulation amongst us, this trip to Gour, and then to Grotowski via Abani, and then taking one step back in time, to Lakshman Das, must have been our own attempt at tracing the course of a journey, albeit backwards.

And now when I am writing this note, we are in the process of going further back from the brothers Lakshman Das Baul and Purno Das Baul, to their father, Nabani Das Baul, via Deben Bhattacharya, Albert and Sally Grossman and Allen Ginsberg, having discovered in the archives of the British Library. a recording of Nabani Das Baul in performance in 1956, made by none other than Arnold Bake.

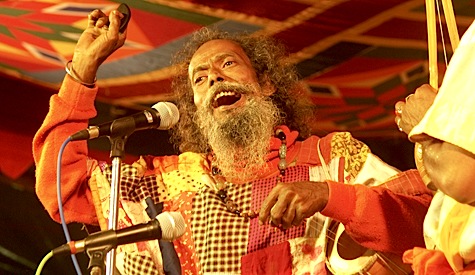

I am never comfortable writing about baul matters, because I feel utterly confused by its anthropology, sociology as well as baul as a form of performing art. There are many scholars to write about such things. I think that at The Travelling Archive, we are drawn to the power and beauty of this music, and we are also interested in the stories which come out of the lives of those who sing this poetry which is layered with meaning. In 1967, Purno Das Baul, Lakshman Das Baul, Sudhananda Das Baul, Hare Krishna Das, Jiban Krishna Mondal and one curious non-baul by the name of Asoke Fakir (who is a central character in Deborah Baker’s book A Blue Hand: The Beats in India, had gone on a US tour. Our conversation with Lakshman Das Baul starts from there.

Lakshman Das Baul in his home, Suri, Birbhum

‘Like Purno, Laksman has fond memories of America and is proud of having been asked to go there,’ writes Charles Capwell in Sailing on the Sea of Love: The Music of the Bauls of Bengal, a pioneering study on the songs of the bauls, first published in 1986 and then from Seagull Books in 2011. ‘On his mailbox,’ Capwell continues, ‘in the manner of Indian gentlemen of the last century who had been to the UK to study, he has written “Laksman Das Baul, U.S. Returned.” Laksman’s impressions of America can be summed up in his statement that the gods and great beings who once inhabited India have been reincarnated in America.’

When we met Lakshman Das Baul, he still remembered things, but he had also forgotten details and was getting confused; perhaps he did not care so much to remember either. His home in Suri was filled with people and things, hence also with time. The US trip had receded to the background, now his sons Sukdeb and Mahadeb were carrying on with the singing, but they were not the shining stars of this time, hence there was a sense of fading out of the light.

Thousands of songs, he said, thousands of songs. I got from my father and I am leaving with my sons. And so many places, where to begin to tell the story? I had bought a pair a shoes from Kalighat, and walked for a few days in them to prepare to go. They took us to San Francisco instead of New York, so we stayed there and also played some gigs. Albert Grossman, the producer of our tour, had arranged it all. But my feet were covered in blisters and they hurt very badly. Sally looked after me. I could not perform, but had to have an operation. Then when we came to Bearsville, not far from Bob Dylan’s house, Sally would stock our kitchen with food, and if there were things left over from two or three days, she would throw everything and get new supplies. There were apples in the garden. So many apples. I would cook chicken with apples instead of potatoes. Dylan loved my cooking. He would keep coming back for the food.

Purno Das and Lakshman Das on the cover of Bob Dylan’s album, John Wesley Harding.

(https://www.expectingrain.com/dok/who/h/hardingjohnwesley.html)

Interestingly, after a gap of decades, Sally Grossman had started to come back to Bengal to work with the Bauls in the 2000s to create their Baularchive, and so when we met Lakshman Das in 2009, he had also started the process of reconnecting with own his past. Some memories had returned to him, but in our presence too, some memories were reignited. We talked about Allen Ginsberg, who had been instrumental in connecting the bauls with the Grossmans, which kicked off their American journey in the late 1960s.

‘Allen was my friend. I taught him some asanas. When he came to our home in Suri, Baba had had a stroke and he was paralysed. He could not move at all. So I had to do everything for him. He would be drooling, and Allen cleaned his mouth with his hands.’

‘From Tarapith, Asoke brought Allen, Peter [Orlovsky], and Shakti [Chattopadhyay] to Suri, where he knew of a large clan of Bauls. There Allen found the aged Nabani Das Baul on his deathbed, half-paralyzed and unable to wander farther. Upon being introduced, the old man said of Allen and Peter, “They are born Bauls, they will spread the Baul message, and true peace, friendship and dharma will arrive.” Sitting at the old man’s bedside, Allen took down Asoke’s translation of the old man’s quavery song.

‘O blue dressed woman why don’t

You put on your blue dress again

Put vermillion on yr forehead

& come before me as a lover,

& wind and bind and plait my hairs …

I came to play the flute in Brindaban

Now I give the flute to you

young girl– …

Why don’t you take my flute

& let it sing on yr lips

Radha Radha Radha

‘A Baul is only helpless, it is said, before the sound of Krishna’s flute.’ (Deborah Baker, A Blue Hand)

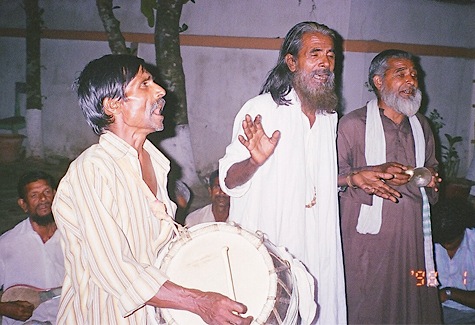

Lakshman Das Baul passed on 21 April 2015. His son, Sukdeb Das Baul, who sang for us on this day in 2009, has also died. Lakshman Das Baul cared for the song to live; in our recording you can hear him introducing his sons Sukdeb and Mahadeb. Does Mahadeb continue to sing? Do his children sing with him now?

Photos from the recording session in Lakshman Das’ house in Suri, Birbhum

‘According to Purno and Laksman, their family has been baul for seven generations, but it is difficult to get more specific information from them about those generations,’ wrote Capwell. Whether to call it baul or not can be a matter of debate. What is baul, who is a baul, what it means to be of baul lineage–it is not for me to enter into this space of critical thinking, I do not have the wherewithal to do so. I do not feel much interest in pursuing such questions either. However, there is a story of love and care from father to child which we heard and saw that day in Lakshman Das Baul’ home, and let us end our session note with it. But first a prelude.

Do you remember recording at the Big Pink with Garth Hudson? Every name from that time does not ring a bell. There was a drummer named Levon Helm, you remember you rolled him a joint? Very potent it was, but then you told him about your father and how he used to mix snake head with the weed… This time Lakshman Das Baul’s voice lit up. Shaaper mathar churno, he nodded.

‘The Bauls had long black hair braided to the waist and were wearing cowboy hats they’d picked up on the drive east from California, where they’d arrived direct from Bengal. (Before heading east in a beat-up old van, they’d played the Fillmore West on a bill with the Byrds.) They loved the bubbling beer sign over our fireplace, and I played checkers with some of ‘em, and we were laughing pretty hard. I was smoking a chillum with Luxman Das, and I said, “Man, that’s some good weed.” He smiled and said, “Very good, but nothing like my father used to smoke—little hashish, little tobacco, little head of snake.” I said, “Wait a minute. Did you say ‘snake head’?” And Luxman laughed. “Yes, by golly! Chop off head of snake, chop into tiny pieces, put in chillum with little hash, little tobacco. Oh, boy! Very good—first class high!”‘ (Levon Helm , 2006, as quoted in ‘Mystic Rites for Permanent Class Conflict: The Bauls of Bengal, Revolutionary Ideology and Post-Capitalism’ by Fabrizio M. Ferrari)

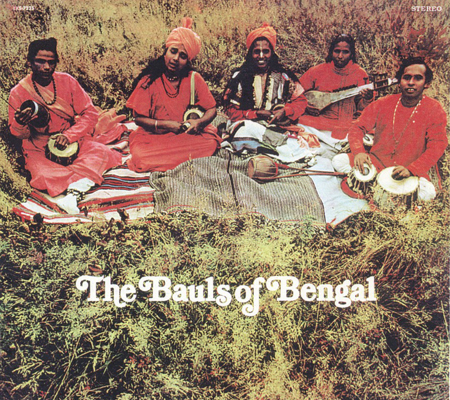

Front and back cover of ‘The Bauls of Bengal’ LP. This is one of the many records which came out of the 1967 trip.

Nabani Das Khepa Baul was a heavy smoker of weed and many have written about how he would smoke up and get into a trance while singing and dancing. By the end of his life, following his stroke, this Khepa Baul was so severely paralysed that he could not even smoke anymore, Lakshman Das told us and you can can hear it in this recording. ‘Then I would go to the market, get the ganja, prepare a chillum, take a deep drag and then breathe into Baba’s mouth. That is all that I could do. It would give him some peace.’ That image has stuck to my mind as one of resuscitation–a beautiful image of holding on, of son helping father live.

Written by Moushumi Bhowmik. Page designed by Sukanta Majumdar, Aug, 2020

Related link:

https://www.anandabazar.com/supplementary/rabibashoriyo/story-of-nabani-das-baul-father-of-purna-das-baul-article-by-moushumi-bhowmik-1.1193096 (accessed in Aug, 2020)

This is a ‘lesson’ I had with Nirmalda, Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur, at the home of his cousin, Milan Mitra Thakur, both of the Mitra Thakur family of Mainadal, in Birbhum, who were recorded by Arnold Bake in 1933. The song I am drawn to is one we first heard during their Janmashtami and Nandotsav festival celebrating the birth of Krishna, in 2014, when we were in Mainadal. That was our first trip to the village, on the trail of sounds left to us by Bake. Nandotsav is an elaborate two-day festival of singing and dancing and rituals; this song about the birth of Krishna to Jashoda, the queen, in the home of Nanda, the cowherd king, was among the many songs we heard that day and I don’t think I took any particular notice of it at the time of the singing, Only when I heard it later on our recordings from that day that I began to play this section again and again. Then I called Nirmalda and asked for the words and their meaning. Before this day in 2018, therefore, I had been following this song and making room for it in my own cycle/circle of songs for several years.

Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur and Moushumi in the home of Milan Mitra Thakur in Bolpur, Birbhum, going through kirtan recordings of Arnold Bake and related recordings of The Travelling Archive.

17 June 2018 was a day heavy with rain, our first monsoon clouds of Asarh having just arrived. So, we can hear the rain throughout this recording. Milanda and his wife lived in a unique room at the time. Milanda is a painter and you could feel it in the way everything was in the long single room on the first floor, circumscribed by a balcony, with parallel walls lined with windows. That room was everything for them–bedroom and kitchen and studio and living room; bare floor, bare walls, minimum furniture, a single bed, Milanda’s canvases and brush and paint stood in one corner, the kitchen things in another–everything neatly arranged. In this recording, while we are singing and talking, tea is being made and we can hear Milanda and Kona Boudi (his wife) talking too. They are concerned about my health, and advise me not to drink too much tea because it disturbs my sleep. I laugh and say I need to have tea all the time.

Milan Mitra Thakur, sitting on a mora, Nirmalendu MItra Thakur on the floor. The curtains are drawn as it is raining outside.

নিদে অচেতন রানী, কিছুই না জানে/চেতন পাইয়া পুত্র দেখিলা নয়ানে (বয়ানে)। The queen lies unconscious in sleep. Awakened she sees her son’s face. ব্রজরাজ বলি, রানী/ রানী, ডাকি ধীরে ধীরে/শুনিয়া আইলা নন্দ সূতিকা মন্দিরে। ‘Borojoraj’, (King of Braj), the queen whispers. Hearing her call, Nanda comes to the birth-chamber. হরল চেতন দেখি আপন তনয়/লাখি পূর্ণিমা চান্দ জিনিয়া উদয়। He sees his son and is lost for words; as if a million full moons have struck. যে যায় দেখিতে, পুনঃ না আসিতে পারে/যদুনাথ দাস ভাসে আনন্দ সাগরে। Who goes to see [this birth/the child], they cannot return. Jadunath sails in the ocean of joy.

This telling of the story is very interesting, for it seems here as if Jashoda* is in labour and she is birthing Krishna. The myth however is that Jashoda is Krishna’s foster mother; Nanda his foster father. Krishna, who is not human at all but god born as a human child, must be saved from a political conspiracy, or he will be killed at birth. He has come to save the world, so he must be saved; separated from his birth parents Devaki and Basudev, and found a safe home. That is how Krishna is ‘born’ in Nanda’s home.

The festival of the Mitra Thakurs of Mainadal with their five century-old legacy of Krishna and Chaitanya devotion, has the dual name of Janmashtami and Nandotsav, thus celebrating both the birth of Krishna, the god, his arrival on earth, as well as his arrival in the house of Nanda and into the arms of Jashoda. The festival is grand in scale and meaning. it is also familial and intimate. Thus they sing the tenderness of the love between the parent and the child. Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur fondly remembers his Sejda, the famous Nabagopal Mitra Thakur, who was recorded by Arnold Bake 1933, and then again by Deben Bhattacharya in 1954, and who had taught him this song.

Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur and Moushumi listen to old recordings. Kona sits in her little corner

On this day in 2018, we sang this together, while talking about many other things, including reminiscing about visits of other scholars to Mainadal, talking about old photographs and worrying over the future of Mainadal. The Mitra Thakur tradition of kirtan singing is essentially patriarchal, their girls do not sing in the family temple or at their festivals. Hence there is some irony in Nirmalda teaching me, a woman, their song, and even telling me that I must let them know if ever I sing this song on the radio, so that they can listen.

Written by Moushumi on Janmashtami 1427 BS (12 August 2020)

*Note that the name Jashoda would be written as Yashoda in most parts of India, but in Bangla we pronounce our ‘ya’ as ‘ja’, and our effort in The Travelling Archive is to stay close to the sound of the language, where possible, although we cannot always do this with consistency. Working across languages, I am often–mostly unsuccessfully–grappling with the question of how to write sound with signs.

Filmed by Anadi Biswas, Sukanta’s Bangladeshi student at Roopkala Kendro, Kolkata, who had come to meet us in Faridpur from his home in Gopalganj. This is a rare video, because in all our years of work, there is hardly any record of our own process, we have almost never turned the camera upon ourselves. In fact, we don’t usually make video recordings and even when we do, the video only complements the audio. Our voices are recorded of course, because we are part of conversations. There are some stills too, usually me taking photos of the recording process. Sometimes Sukanta will place his recorder somewhere and take photos; occasionally he will go to the extent of recording with one hand and taking photos with the other. Sometimes I will record too. Now with our mobile phones fitted with reasonably good cameras, we make more video recordings than before, but here we are talking about 2013. Anyway, the point is that, whatever and however we record, we don’t really record ourselves. One big reason is also this that we don’t usually go anywhere as a big group and there is sometimes just the two of us; we also work solo. There is always too much to do and no time to look at ourselves.

This was different. We had a film school student who was trying out his own skills, zooming in on the leaves and fruit as Habib sang Lalon and Salamotbhai walked through the trees.

Self-portrait, Anadi

The other point to make is that, this was a special moment in our field recording work, and it must be read as such. This is not us going to the ‘field’, summoning singers to where we are lodged. and recording them. That is not at all our process. We met Habib several years ago, through Salamot Khan, whom we had met in 2006. We have listened to him for years, often to his same songs and stories. We have zoomed in on him as he have zoomed in on Faridpur–going to the same shops to eat, same songs to listen, same faces to see. ‘Now that I know your face by heart, I see’, wrote Louise Bogan in her ‘Song for the Last Act’. Faridpur is like that for us. Therefore, this was a gathering of old friends and a celebration of our lasting friendship. The place was an orchard of a friend of Salamotbhai. Sanjay Sikdar, our old friend from Faridpur, was with us and he always is.

Paan-biri break

I am uploading this video on the anniversary of Salamotbhai’s passing.

Written by Moushumi on 12 August 2020

Ma Manasa idol, Jelepara, Munsiganj

Recording session at Jelepara

Mundapara women

We went on this trip on the trail of Arnold Bake’s Santal recordings of March 1931. We went to Kairabani where Bake had recorded students at the Baptist mission school.

Babita Murmu’s Boge Gupi Do was sung in response to Bake’s recording of the same song, which can be heard here: https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Arnold-Adriaan-Bake-South-Asian-Music-Collection/025M-C0052X1641XX-ZZZZV0 (accessed 25 July 2018).

Biditlal Das

On 9 June 2016, we were invited to take part in a public arts event in Sarsuna, an area on the south-western end of Kolkata, around an artists’ residency project called Chander Haat (www.chanderhaat.org). This event was called ‘Sarsuna Theke Jana’ or ‘Derives from the Metropolis’ and it was curated by Sayantan Maitra Boka of Shelter Promotion Council (www.shelterpromotioncouncil.com).

As we began to explore the area, contemplating what we could do by way of taking our work to this event, we realized that this area was largely immigrant territory and that most of the people who had set up home here had arrived from Bangladesh over the past two decades or so. Hence these were new immigrants and were quite different from the old refugees of the time of Partition, or even 1971.

Women of Sarsuna singing Manasamangal

Many of the families were from Barisal in Bangladesh, we learned. One of the visual artists also taking part in the event, Mallika Das Sutar, was working around the Manasa Mandir, which is the temple of Manasa or the Snake Goddess. Mansa is of course big in Barisal and Bijoy Gupta’s Manasa Mangal or narrative in praise of Manasa, is read through the monsoon month of Sraban. In fact, in 2012 we went around different places in Bangladesh to record Manasa’s songs. Here Mallika’s installation involved the local women’s live performance of Manasa’s songs.

We entered into this space of Mallika’s installation and talked with the women who had gathered and recorded some of their songs and stories, as a prelude to a recording session we will have there later, in the month of Sraban (July-August). This was also for us an extension of our ongoing work on Manasa, and a direct continuation of our work in Barisal in 2012.

Mallika Das Sutar’s installation. Clay idols and models made by the women of Sarsuna

Here the women are singing that part of the story where Manasa makes a deal with Sanaka, when she begs for a child, after all her sons have been drowned by Manasa’s curse. ‘You may have a child, you may name him Lokkhindor, but I will snatch him away as soon as he is born,’ Manasa says. Sanaka says, ‘No, that is unacceptable.’ The deal-making goes on. Sanaka is adamant; she will have a child. Manasa relents and finally grants her a son who, she says, will be snatched away on his wedding night. This Sanaka accepts for she then thinks that she will not give her son in marriage and that will solve the problem for her. The story of course becomes far more complex and tangled up. Here they only sing a short extract from the long story. The women who are leading the song are Chandrakala Roy, Malati Majumdar, Parul Sheel and Parul Halder. There are many more who have gathered.

Written in 2016.

Bhungur Khan and his team of Manganiyar singers from Barmer in Rajasthan had been invited to our 10th Baul Fakir Utsav in Jadavpur Shaktigarh in January 2015. For some years we had been inviting a team of bhakti/sufi singers from outside Bengal, to come and sing songs which would have some overlap with the songs of our bauls and fakirs in Bengal. Hence Prahlad Singh Tipaniya (http://www.kabirproject.org/profile/prahlad%20tipanya) came once with mainly his songs of Kabir; then there was ere the qawwals of Rampur, Mohammad Ahmed Warsi (https://soundcloud.com/irfan-zuberi/ustad-mohammed-ahmed-warsi-nasiri-qawwal). So, the Manganiyars came with Kabir, Mira and also songs from further West, such as Bulleh Shah.

They performed at the main festival on 10 January and then the next morning we met in the festival grounds and I suggested they could come to our house, to which they agreed and came along. So, in effect this became a recording session of The Travelling Archive. Sukanta recorded in our living room. These wonderful musicians sang something like five songs, quite getting into the mood of singing. Here they are singing a song of rain, love and longing, such as our bichchhed songs are.

Bhungar Khan is playing the khartal or castanet, Mehru Khan plays the harmonium and sings; Pappa Khan plays the dholak. Din Muhammad usually plays the kamayrcha, but here he had not brought his instrument, so he sat and listened.

Written in 2016

From left to right: Din Muhammad, Pappa Khan, Bhungar Khan and Mehru Khan

Related links

https://saxonianfolkways.wordpress.com/2013/06/03/music-masters-from-the-desert/

https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Bards_Ballads_and_Boundaries.html?id=b30HAQAAMAAJ

Tuntun Fakir of Kushtia in Bangladesh had come to sing at our 10th Baul Fakir Utsav in Jadavpur, Shaktigarh in January 2015. The tenth year was a very special occasion for us, for while it marked a milestone in the life of the festival, for some of us it was also a closure of sorts, for things were rapidly changing all around us and the festival could not remain as it was in these ten years. That though is topic of a whole separate discussion. Anyway, there was a team of bauls who had come from Kushtia this time.

After the performance tent had been set up, and the sound was in place, Sukanta declared that now he would go around making his own recordings (for The Travelling Archive). So, he went over to where the artists who had come to the festival were staying and made recordings of those informal sessions of singing and talking.

Tuntun Fakir at the festival. Photo: Amit Roy.

Tuntun Fakir has come many times to many festivals on this side of the border. Hence he is not physically so ‘opaar’ as he sings in the Lalon song, not so ‘un-take-across-able’. In fact, he does not care for lawful papers or anything–he is one of those people, like Laila in some ways, who lives in defiance and denial of the border. (Such acts of subversion will become more and more difficult as our cities and countries become more and more walled). Yet, metaphorically, the ‘opaar’ he sings about is the state we all are in, where we are unable to move without help, unless someone shows us the way and takes us across. Tuntun sings in the style of Kushtia, where song is more like a beautifully delivered sermon. He will remind the listener of Khoda Baksh Sai song also of Nazrul Fakir, Ajmal, even Binoy Nath, whom we had recorded way back in 2006, in Faridpur.

Written in 2016.

Mainadal is a village in Birbhum district, West Bengal, 215 km northwest of Kolkata. It is home of the famous Mitra Thakur family, known for their practice of kirtan around the shrine of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, who has been their house deity since the beginning of Vaishnavism in Bengal, about 500 years ago. We reached Mainadal tracing a link from a set of sound recordings in the archives of the British Library. These recordings, made on wax cylinders by the Dutch scholar Arnold Bake in 1933, mention both Mainadal as the place of recording and the Mitra Thakurs as the artists being recorded–Haridas Mitra Thakur, Haladhar Mitra Thakur, Advaita Chandra Mitra Thakur, Nabagopal Mitra Thakur, Sanket Bihari Mitra Thakur, Gour Gopal Mitra Thakur and Kaliakanta Mitra Thakur.

It was a bit of an adventure identifying the place and the practice and then finding the contacts through whom to reach Mainadal. But once contact was established, things began to flow quite smoothly. The Mitra Thakurs heard of our interest in their music and invited us over to their Janmashtami or Nandotsav festival, which is the celebration of the birth of Krishna.

So, we went to Mainadal for the first time on 19 August 2014. Arnold Bake had been there 81 years before us; his recording dates were 12-14 August 1933, and we know now that in 1933, that was indeed the time of Nandotsav–the end of the monsoon month of Sravan and the beginning of Bhadra.

Mainadal old temple. Photo courtesy: Milan Mitra Thakur.

Old photographs of the annual festival of Mainadal. Photo courtesy: Milan Mitra Thakur. Photos taken by Pulak Dutta and Masyuaki Onishi during their trip to Mainadal in 1980.

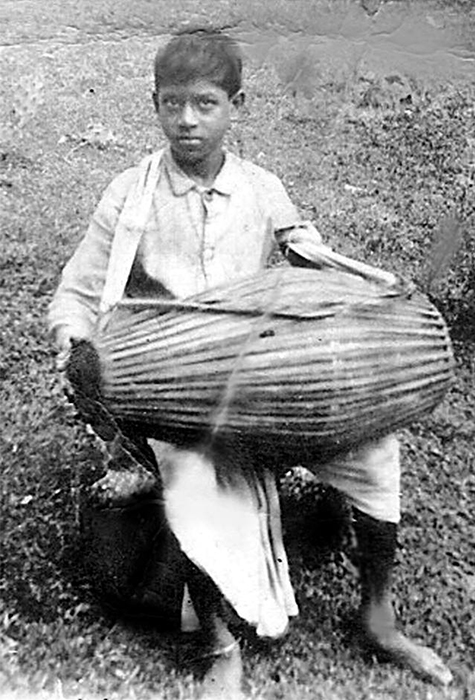

An eminent mridanga player, Kaliakanta Mitra Thakur.(or Kaliyakanta, as Arnold Bake wrote). This photograph is at least 80-85 years old, when Kaliakanta was a boy of eight or nine.

Milan Mitra Thakur sent us this photograph and wrote in an email: “মিত্রঠাকুরদের শৈশব শুরু হত এই পথে। শৈশবেই নির্ধারিত হত জীবনদিশা। এই ফোটোগ্রাফটি মৃদঙ্গ-বিশারদ কালিয়াকান্ত মিত্র ঠাকুরের (নির্মলের বাবা) ৮-৯ বছর বয়সের ছবি।”

Who might have taken this picture, is a matter of speculation. In fact, who took all the rest of the old photographs? Could it have been Arnold Bake himself? After all, he took pictures and sometimes filmed too wherever he went, especially for recording. Besides, Kaliakanta was recorded by Bake, along with his father Haridas Mitra Thakur. The British Library shelfmark is C52/1918 and the note in the catalogue reads like this: ‘Bake India II, No.269 (1931-33). Male solo recitation with drums and cymbals. Bake’s notes: “Kirtan from Mainadal 12-14/8/’33. [Kirtan tals] 12. shashishekara, 14. bororupak, 19. ?oj [Doj]. Haridas M.Th. [Mitra Thakur] cymbals with mistakes Kaliyakanta M.Th.” Reasonable quality recording.’

We have recorded many sessions of music performed by Kaliakanta’s sons, Nirmalendu, who is a beautiful singer, and Sachchidananda, one of the last remaining musicians to hold the great tradition of the Mitra Thakurs’ khol playing and recitation of what Bake called ‘drum poems’.

The large and extended family of the Mitra Thakurs were not aware of Bake’s visit to their village all those years ago; as a matter of fact, they had no idea who Arnold Bake might have been. When we told them their own story, they were truly excited. As I read out their ancestors’ names from my notebook, they responded with, ‘Oh, he was my grandfather! He was my father!’ and so on.

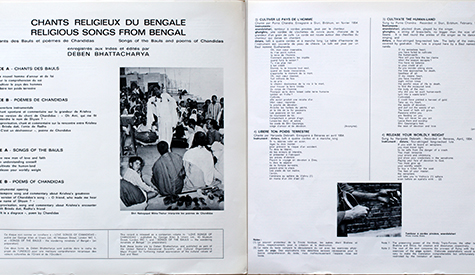

Manik Mitra Thakur watching photographs taken by Arnold Bake

That was the beginning of a relationship for us, for since that first meeting we have gone back many times to Mainadal, stayed overnight, recorded some beautiful music, while some of the Mitra Thakurs–Milan, Nirmalendu, Putul and so on–have become close friends. We did not have copies of Bake’s recordings with us when we first went to Mainadal (although now the British Library have taken the lead from our work and sent to the Mitra Thakurs digital copies of their recordings), but what we did have was some silent footage from Bake’s films (which we had from ARCE-AIIS) of what we thought was kirtan from Mainadal, although we were not so sure about them. So we wanted to check this out with the Mitra Thakurs. We also had a copy of a recording of Mainadal (Mayanadal, as written in the record sleevenotes) kirtan recorded 21 years after Arnold Bake, in February 1954 in Asansol, by Deben Bhattacharya. The singer was Nabagopal Mitra Thakur, who had also been recorded by Bake in 1933. This was from an LP released in 1966 by BAM in France.

The cover and the record

So we played to the Mitra Thakurs these audio recordings and showed them the images of the record covers and silent footage we had with us. We went especially to the oldest family member, Manik Mitra Thakur, to record his response to these recordings and images, and what stories he might have to tell us. And, it was from here that we were directed towards Mongoldihi, for the octogenarian Manik Mitra Thakur and his sons identified the footage as being of the Ras festival of Mongoldihi, another village of Birbhum. Then he saw the photograph on Deben Bhattacharya’s record which had Nabagopal Mitra Thakur’s name in the caption. That is not Nabagopal, he said. The rest of the family said the same thing. (So then who is on the photograph of the Deben Bhattacharya album?)

Liner notes from Deben Bhattacharya’s record

Anyway, We went round the village, meeting people, talking with them, while the song and dance of Nandotsav went on in the temple grounds. There were many people who had come to the festival. They sat listening to the music, watching the performance, and later all of us would be fed by the Mitra Thakurs; such has been the practice for hundreds of years. Sing, dance, eat and rejoice in the name of Gour or Gora.

ওহে গোরা, ওহে গোরা!

Nityananda Mitra Thakur, or Nitai as he was lovingly called by his family, one of the younger performers of this large kirtaniya family, had a natural charm about him. His movements were supple and as he sang and danced the story of Radha and Kirshna’s courtship–purbaraag or the flowering of love–that love and loving came to life. Nitai’s audiences savoured every gesture he made and every rasa which was aroused. This was performance before the initiated, so the audience knew where to feel what; they knew their rituals of appreciation. Here we have presented clips from that performance.

Later we talked with Nityananda about his performance, training, his lineage, showing him our finds–the Deben Bhatacharya album cover, the Bake footage, the names from BL. We talked about meeting again, about talking more. Something was begun, to be carried on later.

Nityananda Mitra Thakur watching old photographs

On 29 March 2015, I called Nitai, because I wanted to ask him something about Mongoldihi, where I remembered his wife had said she had family. Nitai’s phone rang a few times, then there was a voice on the other side. I introduced myself. There was a moment’s silence, I could hear a breeze hitting against the mic of the phone, so I asked Nitai if he was going somewhere and if I should call back later. Silence again. Are you not home, I asked. No, came the reply. The natural warmth of Nitai seemed to be missing and I wondered what might be wrong. So I asked if I was indeed talking with Nityanananda babu. ‘No,’ said the phone. ‘Nitai has died.’ I could not quite comprehend what he was saying. Beg your pardon? I said. I thought I must have heard wrong. The voice said again, ‘Nitai died last night, on stage, while he was performing. He had a heart attack. We have brought him to the crematorium now.’

So, that breeze and the crackling sounds were of fire and wind from the burning ghat.

This session is dedicated to our unfinished conversation with Nityanananda Mitra Thakur, who died at the age of 48, while in the act of singing and dancing his songs of love and devotion, for Krishna, Radha and Gora.

Written in 2016.

Post Script, added on 14 August 2017.

Referring to the photograph of Kaliakanta Mitra Thakur above, about which we were wondering if it might have been taken by Arnold Bake, we now know from Milan Mitra Thakur that it was indeed taken by him. The confirmation has come from Christain Poske, British Library and SOAS’ research scholar, who visited Mainadal earlier this year.

In this context, we refer to Bake’s letter to his mother, dated 16 August 1933. He wrote: ‘I brought a film but I did not use it because there were no performances during the day. I did take a number of pictures that I will send to Calcutta soon to have them developed. I hope they are nice, but I’m a little afraid . . .’ (Translation: Jan-Sijmen Zwarts). So, Kalianata’s was one of those pictures he had taken during that visit.

Bhaktadas still comes to our street. We had recorded him at home in 2010. Then one day we played him his song on our website. He was very excited to ‘see’ himself on ‘TV’.

With Bhaktadas, nothing seems to change. Only the years go by. We hear his voice, sometimes go out to the balcony, sometimes stay in, some days we go down and meet him. Make plans for another recording session; a recording session that is always a week or two away, as Sukanta tells us.

Bhakta Das in East Road, Jadavpur, Kolkata

ভক্ত দাস যাদবপুর অঞ্চলে কতদিন ধরে গান গাইতে আসছেন ঠিকমত বলা মুশকিল। বিগত বছর তিন-চার নিয়মিত দেখি। মাসে এক, দু’বার অতি অবশ্যই শোনা যায় ওঁর গান। ইউনিক গায়কি আর দোতারা বাজানোর স্টাইলে প্রথম দিন থেকেই ভক্ত দাস নজর কেড়েছেন সকলের। আমার কাছে একটি ছেলে কিছুদিন আগে একটা ফিল্ম নিয়ে এসেছিল সাউন্ড মিক্স করার জন্য; সে এই অঞ্চলেই থাকে একটি মেস বাড়িতে, সেও দেখা গেল তার ছবিতে রেখেছে ভক্ত দাসকে। ওদের পাড়ায় দাঁড়িয়ে তীব্র চিৎকারে, ঢোলা বিরাট সাইজের পাঞ্জাবি পরে আসর মাতাচ্ছেন তিনি।

মানুষটার সম্পদ হল ওঁর গলা। গান গাইলে সদা-ব্যস্ত এই শহরও একবার থমকে দাঁড়িয়ে দেখে নেয় ওঁকে। পাড়ায় ঢুকলে টের পাওয়া যায় অনেক দূর থেকেও। এই কংক্রীটের জঙ্গলে, দেয়ালে দেয়ালে প্রতিধ্বনিত হয়ে গমগম করে বেজে ওঠে ভক্ত দাস বাউলের কন্ঠস্বর।

গানের মাঝে নিজের মত করে কথা বসিয়ে নেবার অভ্যাস ভক্ত দাসের। অনেক চেনা গানেরও নানা অচেনা লাইন তাই মাঝে মাঝেই শোনা যায় ওনার কন্ঠে! কেউ ওঁর গানে শুদ্ধতা খুঁজতে গেলে বিপদে পড়বেন। ও গানের রস তার সপ্রতিভ মেজাজে, তার ইউনিক সাউন্ডে। আমরা তো এত জায়গায় যাই, কত রকমের মানুষ দেখি, কিন্তু এই একটি মানুষকেই দেখি যিনি সত্যি সত্যিই ভবঘুরে। ভাবে নন, স্বভাবে যথার্থই কিঞ্চিৎ বাতুল। মাঝে মাঝেই অনেকদিন আসেন না। তারপর হঠাৎ একদিন শোনা যায় সেই বিরাট আওয়াজ। এসে প্রত্যেকবারই বলেন কামাক্ষ্যায় গেছিলেন। আমাদের কয়েকটা রুদ্রাক্ষের ফলও দিয়েছেন একবার এ পকেট সে পকেট হাতড়ে। একদিন এসে আমার শরীর খারাপ শুনে বললেন, “আমি গান গাইছি একটা, সব ঠিক হয়ে যাবে”। বলে নিজের সুরে নিজের কথায়, মা আমার বাবাকে ভাল করে দাও ইত্যাদি বলে একটা গান গেয়ে চলে গেলেন। আমাদের বলেছেন এখন অশোকনগরের (উত্তর ২৪ পরগণা) দিকে কোথাও থাকেন। কথা শুনে বোঝা যায় কোনও কালে বর্ডার পেরিয়ে চলে এসেছেন। কন্ঠে নিয়ে এসেছেন বিচ্ছেদের সুর। প্রথমদিকে বেশিরভাগ বিজয় সরকারের গান গাইতেন। ইদানিং শহরে কলেরার মত ছড়িয়েছে, “হৃদ মাঝারে রাখব”। আগের উল্লিখিত ছবিটিতে দেখলাম তাই গাইছেন নিজের মত করে। লোকে পয়সা-টয়সা দিচ্ছে।

ভক্ত দাসের গাওয়া বিজয় সরকারের গান আমাদের ২০১০ এর একটি রেকর্ডিং সেশনে আছে এই সাইটেই। এই সেশনের ছোট ভিডিওটিতে ওঁর যাওয়া আসার একটা ছবি ধরা রইল; যেভাবে আমরা এখন ওঁকে দেখি আমাদের চারতলার বারান্দা থেকে। আগে উনি এলে নিচে যেতাম কখনো, আর যাই না এখন। উনিও জানেন। বারান্দার নিচটিতে দাঁড়িয়ে গাইতে থাকেন যতক্ষণ না এমরা একবার বারান্দায় বেরোই। দু’একটা বাক্য বিনিময় হয়, তারপর চলে যান। ইদানিং নিজেরই মত আর কোন এক গায়ককে নিয়ে আসবেন বলছেন আমাদের কাছে গান “শুটিং” করাতে। সে তো এখনও হয়ে উঠল না। প্রতিবারই বলেন কোন এক শনিবারের পরের শনিবার আনবেন তাকে! আমরা সেই পরের শনিবারের প্রতীক্ষায় আছি!

Written in 2014.

I have known Ibrahim Boyati for almost two decades; from the time of the shooting of Tareque Masud’s ‘Muktir Kotha’ in 1998. I was at the rehearsals with him and Muhammad Shah Bangali, a singer and composer from Chittagong, whom the ethnomusicologist Deben Bhattacharya had recorded in 1971.

As I write these lines, I think of the layers of sonic history contained in them. If an archive is the future of the past, as Alexander Stille calls it, then the present, the moment of the creation of sound, which is also the moment of its death, foretells the future. Who would have known that when a man from Paris had recorded refugee songs in an emerging Bangladesh in 1971, those sounds would find new meaning in a film made more than 25 years later? Who would also know that the young, blind and ever-smiling dotara player accompanying the singer on the sets of Muktir Kotha, our Ibrahim Boyati, would tell us his story of ageing with music; rather, of never ageing, in the two decades to come?

Late in the evening on 17 January 2013, we went to meet Ibrahim Boyati in the mazar of Khoka Pir in Faridpur town, where he can often be found. We went to ask him if we could have a session with him the next day, for it has been some years since we last recorded him.

Ibrahim bhai is a treasure of The Travelling Archive. He has enriched the space of our archive in non-replicable ways. Which is why when we see him in fear, looking hither and thither in the darkness with his blind eyes before whispering a promise to come to us the following day, as if we were hatching a plot; when he tells us in gestures about the silencing of the song; we feel ashamed for having taken part—directly or indirectly—in the process of this silencing.

We are a hapless people, who do not know what past to keep for the future. Ibrahim bhai had wanted us to shut the windows of the room where we were recording him on this winter morning in 2013. I still have my songs, he seemed to be saying, but I dare not sing them everywhere.

As we listen to him, over and over, in the recordings Tareque made for Matir Moyna, in our recordings of 2004, 2006, 2009 and now in 2013, we need to ask ourselves this singular and simple question: Why did Ibrahim bhai ask us to shut the windows that day, while he was singing?

And now for Sukanta, the keener listener’s story.

Recording Ibrahim Boyati

ইব্রাহিম বয়াতিকে যখন ২০০৬ সালে ফরিদপুর শহরের কাছে উত্তর শোভারামপুরে সাদেক আলির খামার বাড়িতে রেকর্ড করি, ওঁর গলা শুনে তো আমার পড়ে যাবার অবস্থা!

তারেক মাসুদের মাটির ময়না ছবিতে আগে শুনেছিলাম ইব্রাহিম ভাইকে। কিন্তু সামনে থেকে ওই ঈষৎ কর্কশ অথচ মধুর গলা, কখনো একটু কম-লাগা সুর আর অতুলনীয় দোতারা বাদন শুনে ব্লুজ গায়কীর কথা মনে পড়ে যাচ্ছিল।

অতিথিপরায়ণ সাদেক আলির সৌজন্যে শীতের সকাল সকাল সকলের খেজুর রসের পায়েস জুটেছিল। সেই খেয়ে দিনভর গান হল খুব। সেই আসরে ইব্রাহিম ছাড়াও আরো দু’একজন গায়ক ছিলেন, সাদেক আলি নিজে ছিলেন, তবু সবার মধ্যে কাঁচা-পাকা গোঁফ দাড়ি আর খোঁপা করা চুলের ইব্রাহিম ছিলেন নিজ বৈশিষ্ট্যে অনন্য।

পরে আর একবার ২০০৯ -এর মার্চ নাগাদ ইব্রাহিমের সঙ্গে দেখা হল। এবারে ওঁর বাড়িতে। ফরিদপুর শহর থেকে বেশ দূরের গ্রামে, আমরা খুঁজে খুঁজে পৌঁছলাম ওঁর বাড়ি। আগের রাতে কোথাও ম্যহফিল ছিল, বেশ ক্লান্ত ছিলেন। গান হল না, তবে কথা হল অনেকক্ষণ। ছোটবেলায় “ক্যানভাচার” ছিলেন, গান গেয়ে লোক জড়ো করে ওষুধ বিক্রি করতেন। একাত্তরের যুদ্ধের সময় ঢাকা থেকে পালিয়ে আসার রোমহর্ষক গল্প আছে ইব্রাহিম ভাইএর। এবারে গোঁফ-দাড়ি আরও সাদা হয়েছে। কুড়িয়ে-বাড়িয়ে টাকা জোগাড় করে ছেলে গেছে মিডল ইস্টে কাজ করতে। ছেলের নিজের হাতে সাজানো চাঁদোয়া টাঙানো ঘর, রাংতা আর রঙীন কাগজের সজ্জা, খালি পড়ে আছে। ইব্রাহিমের পকেটে মোবাইল। ছেলের ফোন আসে। মেয়ের বিয়ে হয়ে গেছে। কোলে গোলগাল বাচ্চা নিয়ে সে বাপের বাড়ি এসেছে।

ইব্রাহিম খোকা পীরের শিষ্য। ফরিদপুর শহর থেকে যে রাস্তা অম্বিকাপুরের দিকে চলে গেছে, সেই রাস্তার বাঁয়ে, কুমার নদীর ধারে খোকা পীরের আস্তানা। পীর দেহ রেখেছেন অনেকদিন। তবুও ওই মাজারটির সঙ্গে ইব্রাহিমের ওতপ্রোত সম্পর্ক। নিজের বাড়ি ছাড়া বয়াতির ওই আর একটি স্থায়ী ঠিকানা।

আমরা একথা জানতাম বলেই, ২০১২-র এক শীতের সন্ধ্যায় ইব্রাহিমের হদিশ পেতে আধো অন্ধকার মাজারে হাজির হলাম। অনেকদিন ইব্রাহিমের সঙ্গে যোগাযোগ নেই। ফরিদপুর যাওয়া হয় প্রায় প্রত্যেক বছর, কখনো তো বছরে দু’বারও। কিন্তু ইব্রাহিমের সঙ্গে আর যোগাযোগ করা হয়ে ওঠে না। যতবার সেই ২০০৬-এর রেকর্ডিং শুনি, মনে হয় এই মানুষটিকে জমিয়ে রেকর্ড করা দরকার।

Ibrahim Boyati in Tareque Masud’s film, Matir Moyna.

শীত সন্ধ্যায় আশপাশ নিঝুম। মাজার চত্বরে ঢুকে দেখি বেশ বড় উঠোন। একপাশে পীরের সমাধি ঘিরে বেশ বড় আটচালা, কংক্রীটে ঢালাই করা মেঝেতে বিছানো কার্পেট। আর একদিকে বসতবাড়ি। পীরের পরিবারের লোকজন থাকেন বোঝা যায়। আমাদের হঠাৎ আগমনে অবশ্য বিশেষ কেউ বেরিয়ে আসেন না। আমাদের একমাত্র বল-ভরসা সালামত ভাই অন্ধকার উঠোনে ঢুকে কাকে যেন শুধোন ইব্রাহিমের কথা। আমি ভিতরে গিয়ে দেখি, অল্পবয়সি এক পুরুষ বসে আছেন মাজারের কাছে। তাঁকে ঘিরে জনা সাত-আটেকের একটা দল। সকলেই প্রার্থনারত। অল্পবয়সি পুরুষটিই যে জমায়েতের প্রধান বুঝতে অসুবিধা হয় না। প্রার্থনা শেষে সকলেই তাঁর পা ধরে কদমবুসি করে উঠে পড়েন। ইব্রাহিমকে দেখি সেই দলে। কেউ গিয়ে তাঁকে বলে আমাদের কথা। ইব্রাহিম বেরিয়ে আসেন উঠোনে। প্রধান পুরুষটি নীরবে আমাদের পাশ কাটিয়ে ওপাশের বাড়িতে ঢুকে যান। অন্ধকারে আমরা কেউ কাউকে ঠিকমত দেখতে পাই না। ইব্রাহিম মৌসুমীকে চিনতে পারেন; আমাকে পারেন না। আমাদের উদ্দেশ্য শুনে একটু নীরব থাকেন। একবার বলেন গান-বাজনা বিশেষ করেন না, আবার বলেন পরের দিন অন্য কাজ আছে। আমরা অন্ধকারে পরস্পরের মুখ চাওয়াচাওয়ি করি। এই ইব্রাহিমকে ঠিক চিনতে পারি না। মনটা খারাপ লাগতে থাকে। এতদূর থেকে এসেছি, এতদিনের পরিচয়, তবু এড়িয়ে যেতে চাওয়ার কি কারণ ঠিক বুঝি না। অবশেষে সকলের চাপাচাপিতে পরেরদিন ফরিদপুরে আসতে রাজি হন, আমরা যে বাড়িতে ছিলাম সেই বাড়িতে। ঠিক হয় হাবিব গিয়ে ওঁকে নিয়ে আসবে শহরে।

পরদিন সকালে আমরা অপেক্ষা করি। হাবিবের যা পাগলাটে স্বভাব, আদৌ আনতে গেল কিনা কে জানে! হাবিব অবশ্য আমাদের ডোবায় না। একসময় তার হাত ধরে ইব্রাহিম এসে ঢোকেন। সকালের উজ্জ্বল আলোয় দেখি বয়াতির মুখে একটু বয়সের ছাপ পড়েছে। দাড়ি পুরো সাদা, গোঁফ জোড়া নেই। মুখের ভাবে মনের ভাব ঠিক বোঝা যায় না।

যে বাড়িতে ছিলাম, তার লাগোয়া বিরাট বাগান। ছায়া-ছায়া নিরিবিলি বাগানে আগের দিনই লায়লার গান রেকর্ড করেছি। শীতের রোদ-ছায়া গায়ে মেখে বসতেও আরাম আর কংক্রীটের ফাঁকা ফাঁকা দেয়াল-ওয়ালা এই ঘরে টেকনিক্যাল কারণেও রেকর্ড করতে মন চায় না। কিন্তু বয়াতিকে বাইরে বসার প্রস্তাব দিতেই নাকচ করে দিলেন। অগত্যা ঘরেই আসর বসল।

মনে আছে ২০০৬-এর রেকর্ডিং সেশনে প্রথমেই গেয়েছিলেন, “এলাহি আলআমিন আল্লা বাদশা আলমপানা তুমি”। আমরা ওঁর গলায় বিচ্ছেদ গানের জন্য উশখুশ করে উঠেছিলাম। বলেছিলেন, হবে কিন্তু সবার আগে তাঁর বন্দনা করা চাই।

এবারে শুরু করলেন মাঝভান্ডার শরিফের এক গোঁসাই, রমেশের গান দিয়ে; “আমার প্রেম জ্বালায় অঙ্গ জ্বলে, জ্বালা কি দিয়ে জুড়াই”। প্রথমে একটু আড়ষ্টই ছিল কন্ঠস্বর। ধীরে ধীরে কথাবার্তায় সহজ হল। বললেন শিল্পী হিসেবে যোগ্য সন্মান পাননি বলে মনে করেন। সেই অভিমানে বিশেষ আর যান না অনুষ্ঠানে। দু’একটা বিচ্ছেদ গেয়ে, তারপর আমাদের একটু চমকে দিয়েই গাইলেন নিজের রচনা, “আমার আঙ্গিনার পাশে/ কে বাঁশি বাজায় রে/ বন্ধু, তিলেক দাঁড়ায়ে যাও, শুনি।/ তোমার লাগিয়া বন্ধু/ আমি জাগি সারারাতি রে/ জ্বালাই মোমের বাতি/ পথের দিকে চাইয়া থাকি/ আমার বন্ধু আসে নাকি”।

আমাদের মনটা ভরে গেল। ইব্রাহিম বয়াতি জাত শিল্পী। তাঁর প্রাপ্য মর্যাদা তিনি পেয়েছেন কি পাননি সে বিতর্কে না গিয়েও বোঝা যায়, তাঁর অন্তরাত্মাকে কোন কিছুই দমিয়ে রাখতে পারবে না। সঙ্গীতের ফল্গুধারা সেখানে বহমান।

ভান্ডার শরিফের গোঁসাই রমেশের গল্প (ইব্রাহিম ভাইএর ভাষায় যিনি “অনেকদূর অগ্রসর হয়েছিলেন”), ওঁর মুখেই শুনেছি। রমেশ নাকি গুরুর সামনে নির্ভয় চিত্তে জেনেশুনে বিষ মেশানো সরবত পান করে গুরুর কৃপা লাভ করেছিলেন।

ইব্রাহিম বয়াতির মত শিল্পী চারদিকে দলে দলে ঘুরে বেড়াচ্ছে এরকমটা ভাবার তো কোন কারণ নেই! তিনি স্বাধীনভাবে গান করুন। গুরু-কৃপায় সব গরল নিঃশেষে হজম করে ফেলে সুরে আমাদের মাতিয়ে দিন। ভক্তিহীনের এই প্রার্থনা।

Written in 2014.

We became friends with Nazrul Fakir of Kushtia in our home in Kolkata in the winter of 2012. He first came as our friend Satyaki’s friend. Slowly he started to come on his own; perhaps he felt an affinity. Those days Sudipto was doing his play on Lalon. Nazrul performed in it. So he had to keep crossing the border at Benapole, and that was not so easy. So once the trial of border-crossing was over, he had to find his places of comfort. In his own quiet way, he had made his own friends.

Once he came to us straight from Sealdah station. He brought us a CD of Mamun Nadia, a singer who had inspired him. He would stand on the bank of the Garai river and listen to music coming from the boats. Once they were playing a cassette of Mamun Nadia, a Lalon song, he said, and he felt deeply moved. He wanted to gift us that experience.

Nazrul wanted to take a gift home to his family. He is a man of very few words. But he confided in Sukanta. He said, at home, they don’t know what I do, what I sing. I go to all these places–London, Berlin, Bangalore–but they don’t know what I do. Could you please make me a CD of my songs so I can go home and play for them?

Sukanta’s recording and his note capture the essence of Nazrul. There is nothing more to say. You meet the man in his song. He is what you hear, not an inch less; perhaps more.

Nazrul Fakir

নজরুল ফকির কলকাতায় আসেন লালন-গবেষক, অভিনেতা সুদীপ্ত চট্টোপাধ্যায় ও নাট্যপরিচালক সুমন মুখোপাধ্যায়ের নাটক, Man of the Heart -এ কাজ করার সূত্রে। আমাদের বন্ধু, শিল্পী সাত্যকি বন্দোপাধ্যায়ও এই প্রযোজনার সঙ্গে যুক্ত থাকার কারণে সাত্যকির সঙ্গে নজরুলের সখ্য ও সেই সূত্রে আমাদের সঙ্গে তাঁর পরিচয় ও বন্ধুত্ব। নজরুল কুষ্টিয়ায় থাকেন। লালন সাঁই-এর মাজারের কাছেই। রব ফকিরের শিষ্য নজরুলের স্বভাবটি খুব মিঠে আর ঠান্ডা। কোথাও কোন কিছুর উপর জোর আরোপ করেন না। পাশের ঘরে নজরুল থাকলে বোঝাই যায় না ঘরে কেউ আছেন।

গল্প শুনেছি, ভারতীয় রাগসঙ্গীতের অন্যতম দিকপাল শিল্পী উস্তাদ বড়ে গোলাম আলি খাঁ সাহেবের বাড়িতে কেউ এলে, দু’একটা কথাবার্তার পরেই খাঁ সাহেব বলতেন, “এবার ইজাজত দিলে দু’একখানা গান শোনাই”। হয়ত বিশ্বাস করতেন তাঁর আর মানুষকে কি দেবার থাকতে পারে, তাই নিজের গান দিয়েই অতিথি আপ্যায়ন সারতেন!

আমাদের বন্ধু নজরুল ফকিরের মধ্যেও এই ভাবটি লক্ষ করেছি। নজরুলকে বিশেষ বলতে হয় না গানের ব্যাপারে; আর আড্ডায় নজরুলও অন্য কোন প্রসঙ্গে বিশেষ কিছুই বলেন না। খানিকক্ষণ চুপ করে অন্যদের বকবক শুনে, দু’একটান তামাক সেবা করে একতারায় সুর বাঁধতে থাকেন। তারপরে একফাঁকে অনুমতি নেবার সুরে বলে ওঠেন, “এবার দু’একখান পদ গাই”? আমরা হইহই করে উঠি। নজরুল একটানা গাইতে থাকেন। খান-চারপাঁচ গান অন্তত না গেয়ে নজরুলকে বিড়ি-বিরতিও নিতে দেখিনি। একবার বিড়ি খেয়ে আবার গাইতে থাকেন বিরতিহীন ভাবে। মাঝে মাঝে আবার শুধোন, “বিরক্ত করছি নাকি”!

সাঁইজির যেসব গানে দীন ভাবের প্রকাশ, যেখানে গুরুর প্রতি বা পরম করুণাময়ের প্রতি তাঁর শর্তহীন, সর্বাঙ্গীণ আত্মনিবেদন, সেইসব গান নজরুলের গায়কীতে ভারি সুন্দর খোলে। একতারা ও ডুগি সহযোগে যে শব্দজগত তিনি সৃষ্টি করেন, সাধারণভাবে দেখলে তা ভীষণভাবেই কুষ্টিয়ার নিজস্ব। সেদিক থেকে নজরুল হয়ত কোন ইউনিক সাউন্ড পেশ করছেন না শ্রোতার কাছে। কিন্তু পদ অনুযায়ী গায়কের ব্যক্তিসত্তার ছাপ তো গানের উপর পড়ে। নজরুলের সত্তায় ওই করুণ ও দীন ভাবটি এমন ওতপ্রোত জড়িত, ফকির যখন গেয়ে ওঠেন, “দেখে ভব নদীর তুফান, ভয়ে প্রাণ কেঁদে ওঠে/ এসো দয়াল পার করো…”; অথবা, “ও মেঘ হইল উদয়, লুকালো কুথায়/ পিপাসিত প্রাণ যায় পিপাসায়/ আমায় দাও হে দুঃখ যদি, তবু তুমায় সাধি/ তুমি না তরাইলে কে তরাবে আমায়”, তখন ওই তৃষ্ণার্ত প্রাণের হাহাকারটি আমাদের বুকে বাজে। ক্ষীণতনু ফকিরের জোর সেইখানে। আর কোথাও যে ফকির জোর খাটাতে পারেন না বোঝাই যায়। কোন উটকো লোকের অনুরোধে(না আদেশে সাঁইজিই জানেন) নিজের ছোট্ট থলি বোঝাই করে “ভারত” থেকে সাবান, পাউডার আর ম্যাগি নুডলস কিনে নিয়ে যান! ভয় পেতে থাকেন বর্ডারে কেউ কিছু বলবে কিনা সেই নিয়ে। এসব কোথায় কিনবেন, আমাদের জিজ্ঞেস করেন সসংকোচে।

সংসার পালনের জন্য নজরুল রঙ-মিস্ত্রীর কাজ করেন। ছেলেকে সঙ্গে নিয়ে লোকের বাড়ি রঙ করে বেড়ান।

মহাজ্ঞানী সন্ত কবীর তাঁর পদে বলেছেন, “সাহেব হ্যায় রংরেজ, চুনরী মোরি রংগ ডারি/ স্যাহী রংগ ছুড়ায়কে রে দিয়ো মজীঠা রংগ”।

রজকরূপে তিনি/ রাঙিয়ে দিলেন/ এ অবগুন্ঠন।

সব রঙ ধুয়ে/ উজ্জ্বল করো/ আমার প্রেমের রঙ।

কবীরের বহু পদেই তিনি পরম করুণাময়কে রজকরূপে কল্পনা করেছেন। প্রেমের রঙে ডুবে যাবার আর্তি জানিয়ে এই পদেই বলছেন, “সব কুছ উন পর বার দুঁ রে, তন মন ধন আউর প্রাণ”। দেহ মন ধন প্রাণ সর্বস্ব তাঁকে সমর্পণ করলাম।

কাপড় রাঙানোর কাজ তো আজকাল উঠেই গেছে। আমাদের ঘরবাড়ি রাঙানোর দায় তাঁর ভাবশিষ্যের ঘাড়ে হয়ত স্বয়ং সাঁইজিই চাপিয়েছেন! আমাদের অবিশ্বাসী মন এটুকু বিশ্বাস করতে ভালবাসে।

Written in 2014.

Related link

Sahib Hain Rangrez by Shubha Mudgal

We first met Linkon when we went to their house to record his mother and other women singing the Padma Puran on our first day in Dumra village in the Shalla region of Sunamganj, Sylhet. Our friend and guide on this trip, Suman Kumar Das, also lives in this village although his family originates from neighbouring Sukhline village; Suman belongs to a family of school teachers. Suman now lives in Sylhet town and works as the Sylhet correspondent of Prothom Alo, a widely circulated daily of Bangladesh. Suman is also a prolific writer and has already published many books, mainly on the folk poets of his region; even won awards for his books. Barely 30, he is the pride of Shalla. Linkon’s parents look up to him for guidance; they believe that Suman will show the way to their bright and talented eldest son and take him to a world beyond their enclosed haor.

In these monsoon months, the haor becomes an archipelago. Water from the streams and rivers of the surrounding hills gathers in the low-lying plains of this region and stays that way for months while the more elevated villages float like little islands. Shalla is one such island and it holds several villages—Sukhline, Dumra, Ghungiar Gaon Bazar.

Shafik’s Teashop at Ghungiar-Gaon Bazar, Shalla

That was the evening of 15 August 2012. We had arrived by boat earlier in the day and had set out to record the reading of the Manasa Mangal—they call it the Padma Puran here. Linkon’s house was our first stop. In their small দশ ফুট বাই দশ ফুট room, Linkon’s parents live with their sons. Most of the space is taken up by the beds (we sat on one of them). There is also a desk with books and posters and pictures on the walls. Linkon’s father, Khitishbabu, had a business in book binding; now he makes paper boxes for packaging. Stacks of undelivered boxes lined the room. There is no limit to how much such a space can hold. In the middle of it all, Manasa presided, with coloured paper decoration around her. The women sat singing her praise. Linkon, who now goes to college in Sylhet, had come home, as he knew we were coming. He was doing most of the running around, organizing tea and food for us. There were people outside watching us through the open door. For Linkon, there was pride in this whole affair; he now knows such people, from his stay ‘abroad’. When there was time for introductions, Suman told us that Linkon was a very talented singer.

Suman

On a regular day in the city, Suman and Linkon usually meet in the office-cum-bookshop of Shubhendu Imam, alias Hannan bhai, writer and publisher and proprietor of Boipotro, the leading publishing house of Sylhet. Sumon has found Linkon a job in Hannan bhai’s shop, so the boy can support himself while he studies in an undergraduate college. Sumon often goes there after work to meet with the city’s intellectuals. Linkon naturally comes in contact with such people. Sometimes the ‘bhodrolok’ gathering asks him to sing. When he finishes college, Linkon will be his family’s first graduate. Perhaps he will find a better job then, or go for further studies. But he would prefer to become a singer. He watches television, and aspires to go one day to the young talents shows. He loves the voice of Sonu Nigam. Bollywood has planted a dream in Linkon.

The next day we went by boat to Haripur and Nainda villages, but came back to Shalla by the evening. Then we met at Shafik’s tea shop in Ghungiar Gaon Bazar. The tea shop is on the edge of what has now become a river, beside the ‘Jatri Chhauni’, where passengers wait for the next boat. Here, as evening descended, between cups of sweet tea, Linkon sang for us. The song here is a composition of Shah Abdul Korim, the legendary composer of this region, who died at 93 only a few years ago. Linkon sings beautifully, with great tenderness, but from his singing you wouldn’t think of him as belonging to this region. His voice does not carry marks of the place which birthed him, and which is steeped in the Padma Puran, dhamail, bichchhedi, murshidi gaan. Later we said amongst ourselves: লিংকনের গলা থেকে অঞ্চল মুছে গেছে। Linkon could belong anywhere now. Is this satellite television’s gift to civilization? It wasn’t just a matter of style of singing; Linkon after all was singing a song of his own region. The shift seemed to have taken place in the interpretation. And it wasn’t even a conscious interpretation, in my view. It was more a matter of processing and packaging.

Jatri Chhauni

Korim Shah’s songs, as it is with songs of all mystic poets, have layers of meaning attached to them. On the surface they might be talking about separation and longing, but what this separation is, who or what from, is not spelt out in so many words. You make your own meaning out of a song, depending on who you are and where you are located; also what you want it to mean at a particular moment—a rich composition allows for so much multiplicity of meaning. Linkon’s song, it seemed to me, was losing this complexity, the bhav had changed, it had been reduced to a simple song of love. Beautiful and tender for sure, but made for that notorious ‘box’ as if. Back in 2006, we had met another beautiful and tender singer in Debicharan, Rangpur in the north of Bangladesh, Bipin Roy. He had sung a song not from his region, but from Netrokona in the east. Amar gaaye joto dukkho shoy. song Again there were no signs of a ‘home’ in the song. It could belong anywhere.

Interestingly, while Linkon was singing, a small group of passers-by had gathered in the shop. They were listening to the music but they were also curious about us. Who we were, what we were doing, what instrument Sukanta was holding in his hand, why he was wearing headphones, why we talked in this strange and unfamiliar way—they wanted to know. Our dialect confused them. This wasn’t Sylheti, for sure, but could this be Bengali? We were from India. So, was this Hindi maybe? You speak Bangla in Kolkata, they asked?

Poster announcing a new book of poems by a local poet

One man was more brave than the others. He said he would like to sing too. His name was Shishu Mia, he said. Then he sang. Again it had to be a composition of their ‘national’ poet—Shah Abdul Korim. And when he sang, every bit of his song and his voice became the region. He got his words mixed up, his lines were in disarray, but that roughness, that play with tempo, those cries—they can only come from someone who is rooted in this place. Linkon, by comparison, had become an outsider. I remembered Helal Miah in London. So far from the land of his ancestors, and yet so rooted. Is root then something we can carry with us where we go, and nurture in our new homelands?

From left: Linkon, Dipu, Dharani, Sukanta, Moushumi

Linkon’s song:

কেন পিরিতি বাড়াইলায় রে বন্ধু

ছেড়ে যাইবায় যদি?

কেমনে রাখিব তোর মন

আমার আপন ঘরে বাদী রে বন্ধু?

ছেড়ে যাইবায় যদি।

পাড়াপড়শি বাদী আমার, বাদী … ননদী

মরণজ্বালা সইতে না’রি

দিবানিশি কাঁদি রে বন্ধু,

ছেড়ে যাইবায় যদি।

কারে কী বলিব আমি,

নিজে অপরাধী।

কেঁদে কেঁদে চোখের জলে

বহাইলাম নদী রে বন্ধু,

ছেড়ে যাইবায় যদি।

বাউল আবদুল করিম বলে,

হলো এ কী ব্যাধি?

তুমি বিনে এ ভূবনে

কে আছে ঔষধী, এ বন্ধু

ছেড়ে যাইবায় যদি?

A boat out of water

And Shishu Mia sang:

মন রে তুমি কুপথে যাইয়ো না।

কুপথে যাইয়ো না তুমায় করি রে মানা

গেলে পাইবে লাঞ্ছনা।

তুমি চলো হুশ করে নইলে পড়বে বিপদে,

মন রে তুমি কুপথে যাইয়ো না।

সুজা সরল রাস্তা ধরো

কাম কামিনীর সঙ্গ ছাড়ো রে।

করিম কয় বা ভুল,

তুমি ঠিক রাখিও মূল

নইলে লাগবে গণ্ডগোল।

মন রে, মন রে তুমি কুপথে যাইয়ো না।

তুমি সরল সুজা রাস্তা ধরো

ছয় রুহুকে (রীপু?) বাধ্য করো রে

তুমি করিয়া সিজন [সৃজন?]

তুমার নাম করো স্মরণ, মুর্শীদো।

মন রে তুমি কুপথে যাইয়ো না।

কুপথে যাইয়ো না তুমায় করি রে মানা

গেলে পাইবে লাঞ্ছনা ।

মন রে, মন রে তুমি কুপথে যাইয়ো না।

Written in 2014.

The four recordings in this session come from an ongoing project on Manasamangal or the Song Cycle of the Snake Goddess, Manasa, which we have been recording, bit by bit, in different places in Bengal for some years. The idea is that over a period of time we will have different versions of the story of Manasa sung in different forms and styles across a whole range of places within Bengal and beyond, showing it as a living and evolving tradition.

The Manasamangal, also known as the Padma Puran, is a Mangalkavya sung for Manasa (the Mangalkavyas are devotional paeans to some local deity, composed in Bengal between the 13th and 18th centuries). This ritualistic song cycle is performed as a timeless but also living tradition in Bangladesh and eastern and north-eastern India; even in southern India. It is performed usually in the monsoon month of Sraban, i.e. from mid-July to mid-August, when it is the time of the snakes in a land of flooding rivers and swamps.

Book cover: Baish Kobir Padmapuran

In August 2012, we travelled for 10 days in Barisal and Sylhet, and caught parts of the story of Chand Sadagar, the merchant who refused to worship Manasa, preferring Siva instead; of Manasa’s anger and revenge against of Chand; of the death from snakebite of Lokkhindor, Chand and Sanaka’s last remaining son, on his wedding night, (all other sons were drowned in sea and Chand’s merchant vessels destroyed, before the birth of Lokkhindor); and of Behula (Bipula in Sylhet), Lokkhindor’s newly-wedded and widowed bride, sailing to the heavens with her husband’s corpse with the pledge to return him to life.

There are many tales about the origin of Manasa, a deity of partial godhead (for she may have been born when the aroused Siva’s semen dropped on a lotus or padma flower; hence she is called Padmavati), or she might have been a creation of the sage Kashyap’s mind or manas, hence Manasa. There is also the incident of Manasa losing an eye to the fury of her stepmother Chandi. Whatever her origin, Manasa is a one-eyed goddess who presides over a world of snakes and reptiles, and humans who live in close contact with such creatures. In practical terms, she is worshipped by those who need her protection; that is, those who risk snakebite or stormy rivers and seas in their everyday lives. Manasa is worshipped for her ability to prevent and cure humans of snakebite; she also brings them prosperity and fertility. When praised, she is benevolent and kind; when undermined and humiliated, she is full of vengeance.

Pages from Baish Kobir Padmapuran

In both Barisal and Sylhet, the Manasa Mangal is sung from start to finish through the whole month of Sraban, mostly by women, as a community ritual. So also in Murshidabad, where Sukanta had made some recordings of Manasar gaan song back in 2009, when we did not have such a project in mind but he was only recording sounds for a feature film. Anyway, the fact is that in each place they sing their own versions of the same story, reading from panchalis or texts written down hundreds of years ago by their own regional poets. These poets localise the Manasa story—the land is described in local terms, rivers bear local names, the food is what local people eat—shaak, machchh and so on. . . Such are the signs of any great story, when it can be both local and universal.

The text most commonly followed in Barisal is by Bijoy Gupta, a 15th century poet of Goila, Agailjhara in this southern district of Bangladesh. The text followed in Sylhet, on the other hand, is the Baish Kobir Padma Puran, credited to 22 different poets, prominent among whom is the 15th century Narayandeb. As historical accounts go, Narayandeb’s original home might have been in Rarh in the heart of West Bengal, but it is believed that his family later moved to Kishoreganj, in the east of central Bangladesh. Interestingly, Narayandeb’s narrative is as popular in eastern Bangladesh as it is in Assam, and by Assam we are not only talking about places contiguous with Bengal, such as Cachar, which are in effect extensions of the Sylhet region. We are here talking about places distant and distinct from Bengal such as the Darrang region of central Assam. Here there is a very old tradition of singing and dancing the Suknani Ojapali (or Oja Pali), in praise of goddess Manasa; Suknani being an acronym of Sukabi Narayandeb.

So then, as we move on our trail of Manasa’s songs, listening and watching, recording and writing–for much of the Manasa rituals are also very strongly visual—we get caught in a complex web of overlaps, intertwines and juxtapositions. Enchanting new maps of rivers and forests, poets and devotees, snakes and charms, life and death, open up before us. There is something primeval, yet universal about this world. Behula sails with the dead from shore to shore, but we are assured by fore-knowledge that the dead will eventually come back to life and Manasa’s mangal or blessings will prevail.