Archives: Record Session

From Ruhul Amin to Ahmed Moyez. From Ahmed Moyez to Noman’s house in Bethnal Green in East London, where many of the people I had met about a year ago in Betar Bangla radio station had also come. It was our Bethnal Green Party, a communal celebration of Bangladeshi immigrants, with friends, food and music. The session reminded me of the meetings we used to have at home—middle class and urban, with a mix of poetry, politics and music—art song, protest songs, folk music, conversation and laughter. New rituals of new communities in a new ‘homeland’. Some sans papiers among them. Noman, in whose council house we were having this party, ostensibly ran a small business in printing. In 2010, when we went back to London, we could not find him however. Nor Shahan, someone who worked very closely with us on this 2007 field trip; he had apparently got embroiled in some legal case.

The Ali sisters, Amina, Afroza and another younger one were present; they are all second generation immigrants and their parents live in Kent. However, they had been sent back ‘home’ to have part of their education in Bangladesh. So, they are still quite directly connected with life in Bangladesh. That evening Amina sang a song from the Bangladeshi film O Amar Desher Mati. Her fiancé Sayeem read a poem—he had only just arrived from Bangladesh and was working as a journalist for an East London newspaper. Then there was Tofael, another second generation immigrant, who was more ‘Londoni’ than the others. He ran a translation/interpretation agency in East London. He sang an old Mukesh hit from a 1971 Bollywood film, Anand—O maine tere liye hi saat rang ki sapna chune. Interesting how widespread the influence of Bollywood is. Tofael probably would not speak Hindi, yet these Bollywood songs have crossed barriers of language and become cultural markers of a ubiquitous South Asianness. There were other talks of Bollywood at the party. Amina said how she had learned not to feel so antagonistic towards Pakistanis (referring to Bangladesh’s war of independence against Pakistan in 1971) after seeing a Shah Rukh Khan film.

Recording at Bethnal Green, London

Akash, who worked in the social service sector, was another second generation immigrant, who was more into art and protest songs of Bengal, obviously nurtured in a ‘cultured ,middle class’ environment. He sang the new Bengali ‘anthem’ Ami Banglay gaan gai (I sing in Bengali), a composition of the Kolkata singer-songwriter Pratul Mukherjee, also one of my more widely known songs, Ami shunechhi sedin.

The singer showcased here is Baul Abdul Shohid, not ‘middle class’ like the rest of the people who had come to the party. He was a cab driver, came to London from Sylhet as a young adult in search of work. Found something to make a living from as well as a physical and spiritual community to connect with. Here he sings a composition of Kaari Amir Uddin, a composer of mystical songs, who hails from Sylhet but has now made Essex his home and has many disciples in the community, Abdul Shohid among them.

After the party was over, Shohidbhai drove us back to where we were staying in South-West London, telling us stories of his own journeys as he drove through the deserted streets of a city gone to sleep.

Written in 2013.

Related Link:

Kari Amir Uddin

This was my second meeting with Ahmed Moyez, Sukanta’s frst. I had met him in August 2006 in the office of Betar Bangla–a Bengali/Bangadeshi, more specifically Sylheti, radio station in Bethnal Green. Ruhul Amin, Sylheti filmmaker in London, had taken me there and many other people had also come—mainly students and intellectuals from the Sylheti community. Some knew about my research, some my own music, some were just curious to find out what was going on. For the diaspora, such visits are very important; they help to establish links with the left-home and also to forge new identities in the new home. Music becomes the vehicle for this two-way homeward journey.

Ruhul knew I was looking for songs and stories related to the theme of migration, memory and music and he was taking me around to meet people. About Moyez he had said that this man comes from a family of pirs or the spiritual poet-healers of the Sufi tradition, adding that he is immersed in music.

Ahmed Moyez made a strong impression on me on the first day, but there were too many people around. I hoped to go back to him, with Sukanta. Our recordings from that session and later ones are kept at the British Library (http://sami.bl.uk) and now when I listen to them, I see the story of Ahmed Moyez slowly taking shape. Over the years every time we have met, Moyez has told the same stories and added some new ones; same with the songs. Layers of narrative are added, one over another.

Ahmed Moyez

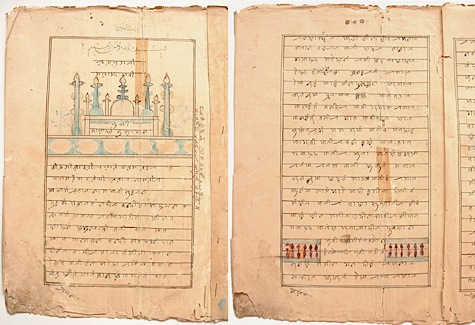

Moyez’s home was in Syedpur, Sylhet, where his poet-philosopher and spiritual healer grandfather, his dada, Pir Mojiruddin, once lived. He knows his grandfather’s songs, talks about his book Prem Ratan, shows some scanned pages from the manuscript. Here in this session, Moyez is singing one of Pir Mojir’s texts. He beats on the empty popcorn tub as if it were his small hand drum or dubki/dofki, and dances to the rhythm of the song, which is about submission to the Creator and about the mystery of creation. প্রাণবন্ধুয়া রে, অপরাধী হইলাম আমি এ কোন বিচারে?

There are fascinating stories about his village life. Moyez talks about how his father healed madmen and women; about how his grandmother would light the lamp every Thursday and offer shinni to the spirits; about how there were spiritual and artistic ways of taking shiddhi or ganja—‘Not quite like how our city intellectuals smoke up for fashion,’ he says. He talks about music being in the air all the time. He studied in a madrassa or Islamic religious school in Sylhet; he says it was there he became aware of the debate of the siddhiwala vs. the shariatwala—those who were free-flowing spiritual teachers, against those who lived by the Book. Which side he is on is hard to say. I suppose back in the days of Pir Mojir it was easier to be either or. Can one be both at the same time? In 2009 after a music session or sadhu-shongo with some Kushtia bauls on Dhaka Art College grounds, there was this young artist, one of the organisers of the evening’s music, narrating to us how terrible he felt to be in India, how Hindu we were and how oppressive. There surely were reasons for him to feel this way. But there was also reason for us to start feeling cornered. We were no longer partakers of the evening’s music, which tells us to go beyond caste, creed and nation, jaat and dharma.

Moyez came to the UK as a young adult, perhaps through marriage—I have never asked him why. His wife is a second, maybe third generation British Sylheti. They have five children. So life is quite complicated now. Moyez’s entire family, even his mother, have left Syedpur and live in London. This route from ‘Sylhet to Bilet’ is an old one (‘The Bengali word ‘bilet ‘ is a derivative of the Persian word ‘vilayet’ meaning foreign land. In this context it refers to England). There are many reasons for people to make these journeys. Bilet holds the promise of a better life, I suppose. Whether Moyez’s life now is ‘better’ than what it could have been in Syedpur. I cannot tell. Maybe he cannot tell either.

Pir Mojiruddin’s manuscript

Better and worse are such relative terms. But with time the place of arrival also becomes home, for better or for worse. Ahmed Moyez lives by the fish market in Shadwell. His family is scattered all over East London, there are friends and relatives in Birmingham; also whole neighbourhoods of Syedpurians in the North Sea coast town of Hartlepool. In 2006 Moyez had told me that in this little town there were immigrant areas where you could hear music as in a village congregation; sounds of drumming and singing typical of the ‘aashor’. In fact this is the story which I found most fascinating right from the start and some day, I want to go on its trail. Perhaps this merely comes out of Moyez’s imagination and I will go and find that it is not like that at all. Instead, Sayeedi’s Islamic waz or religious oration in Bangla will be playing in some corner shop.

At the time of this recording in 2007 Moyez was a part-time journalist of Surma News, an East London newspaper. He lived an almost invisible life then, lost in the crowd. His English was limited, his map of London had only a few familiar streets, beyond which he seemed frightened to travel. But on the streets he knew, he moved about in the relative comfort of his own language, culture and identity.

This East London Bengali/Bangladeshi world is a world within worlds. In many ways it is informed and formed by the country the immigrants come from. It also influences that world, even shapes it, through the power of the GBP and owing also to the fact that it is a part of Bangladesh placed in the centre of the world. Many scholars have researched and written about this two-way impact. Now in 2014, when I am writing this note, Moyez has become editor of Surma News and he also runs a web-design company, Harappa. Has this so-called advancement given Moyez more power in his community? Does this give him a more secure place? Or does this success come for a price? Moyez had organised a presentation for me in Brick Lane in November 2013, where I was to talk about The Travelling Archive. While he was passing the buck to someone to introduce me, I insisted that he does it, as he is familiar with my work. He was hesitant. I don’t know why. I sang a few lines of a song I had learned from one of his recordings; a composition of his grandfather, and then the ice broke. Moyez joined in, like someone who can momentarily forget every other obligation and inhibition, for the sake of the song.

মৃদঙ্গে উঠিছে ধ্বনি, শুনি তার পদধ্বনি রে

We have quoted this song many times in our work. In many ways the song has become independent of Moyez for us. For it is a song about dhwoni or Sound and Listening.

A sound rises from the mirdanga drum.

I hear its footsteps,

It stirs my heart,

I feel in me that rumble and roll.

Why, O why did I hear its call?

Written in May 2014.

Related links:

Bilet–http://books.google.co.in/books/about/Travels_to_Europe.html?id=1jkaZEUm3nEC&redir_esc=y

Scholars:

Katy Gardner http://www.lse.ac.uk/anthropology/people/gardner.aspx

Delwar Hussain

http://www.opendemocracy.net/author/delwar-hussain

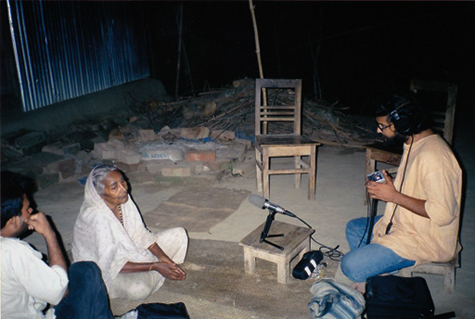

About eight months after we met Hajera Bibi in the courtyard of her house in Ambikapur, Faridpur, the 93-year-old singer and composer passed away, in December 2006. So this is probably the last recording of her voice, or maybe there were other visitors, although when we saw her, she seemed to be living a forgotten life, in silence. Hajera Bibi was one of the first women of East Pakistan, later Bangladesh who gained recognition as a singer and composer in the mystic tradition of bichar, bichchhed and murshidi gaan.

Throughout this recording session Hajera Bibi hovered between forgetting and remembering. We asked her questions, (besides Sukanta and me, there were Sanjay, Pradip and Salamot bhai with us, all of them local), and Hajera Bibi answered as well as she could remember. Sometimes her grand-niece, Jonaki, intervened and said, Dadi is getting it all mixed up. However to us it seemed quite logical and lucid. There was a sense of loss and regret in what she said, expressed in the sounds and fading light of that evening, for she reminisced about her glorious days of evolving as an artist under the guidance of ‘Kobishaab’ or the poet Jasimuddin; about night-long sessions of bichar gaan or song debate with thousands of people listening to her and her favoured opponent, Halim Boyati; about the great composer of Norail, Bijoy Sarkar, being in the audience once; about her days of touring and recording for the radio. What happened then to all the songs she wrote and sang, even recorded? It was hard to imagine that this old woman, slightly bent with age but still able to potter around, sitting in the earthen courtyard of her little house, with few close, poor relations keeping her company—it is hard to imagine that this woman had such a full life once. Age, yes. But what about her glory and fame? And all the money she earned? There is no clear answer for such difficult questions? Or maybe there is the obvious one—who cares? Why is there no recording of her songs? Why no publication? Hajera Bibi told us that some years ago, someone from an NGO had come and taken away her sole surviving songbook; they said they wanted to publish her work; but there was no publication till the time when we met her. She had lost most of her things earlier, in the War of 1971, when her house was ransacked by the Pakistani soldiers; even certificates and gifts she had got for performing in President Ayub Khan’s time. Then she was taken once to UBINIG, an NGO with its head office in Dhaka, which is run by the radical thinker, writer and social activist, Farhad Mazhar. That trip she remembered with fondness. They took great care of her, she said; recorded her, learned songs from her. There were many white people. That was probably the last gesture of love, care and respect she got from the outside world. The rest was her familiar world of family and her shishyas (disciples), mostly powerless people like her. Hajera Bibi quietly died in the house of one her disciples, where she had gone to visit and bless them.

Sukanta recording Hazera Bibi

So much for a whole life spent in music. For being a unique woman who composed and sang songs in erstwhile East Pakistan, later Bangladesh, during a time of great personal and political struggle. Hajera Bibi was born Nonibala, into a Hindu family, married off early and widowed early too. Meanwhile her baby boy had also died. By the time she was 20 or so, her eventful life had come to a halt. How to live on after this? It was as if she could/would have to close the pages of her past life now and start afresh. She found within herself the power of music, also the potential to do music for a living. But this she could not do as the widowed Nonibala. She was mentored by Jasimuddin, converted to Islam, married again, went through wars and struggle, but also developed as an artist and lived in fame. Later she began to write songs in the philosophical and devotional mode.

We went to her, but it was rather too late. That evening she sang, je hale rekhechho murshid, shei hale thaki (O Master, I stay as you will for me). The song came out of her toothless mouth and her frail body, not as a complaint, but as submission. Now if we try to find her lost songs, my fear is that we will not be able to go too far back. Habib sang one of Hajera Ma’s songs in Shambhunath’s tea shop, Laila sang another, also Ibrahim Boyati. They are all from Faridpur. So, Hajera’s songs are still part of the region’s living tradition, at least in some small way. But where to go for more? In 2010 I met Farida Akhter, executive director of UBINIG, who told me that they had Hajera Bibi’s recordings from the time she visited them. They see her as one of their spiritual teachers. Perhaps they will upload those songs on their own website. If they do, we can link our site with theirs. Perhaps someone will have the perseverance to search for old cassettes of ‘Don company who had their offices in Motijheel’, and find some old cassettes of Hajera Bibi. Perhaps someone with a feminist bend will want to know more about her. Maybe someone will get something from the radio’s archives in Dhaka, although it is highly unlikely, considering the state of our archives in the subcontinent, especially government ones. For now, therefore, we are grateful for the songs and stories that Hajera Bibi gave to us, in her own voice, however ‘ultapalta’ (muddled and messy, as her grand-niece Jonaki complained) they might be.

It is easier to pay tribute to the dead than pay attention to the living. A Hajera Mela, or anniversary fair, is being held in Faridpur for the past few years.

Written in 2013.

Chandrabati Roy Barman and Sushoma Das were both born and brought up in the natural environment of song and rituals in villages in the Sunamganj area of Sylhet in eastern Bangladesh, a region known for its music and mystic poets. This was the time before Partition in 1947, for both women are now above 80. We can only imagine their childhood world, but can’t ever return to it, such as the folk poet of Dhirai, also in Sunamganj, Shah Abdul Korim, wrote in his song of nostalgia and regret, Aage ki sundar din kataitam, how beautiful were those days! That was a song about songs –we had so much music then, Korim Shah wrote; baulagan, ghatugan, gajir gan, sarigan, jatragan—he draws up a list. Korim Shah died at 93 in 2009 and the time he is talking about largely overlaps with Chandrabati and Sushoma’s time.

That was a time of plurality of faiths in society, mainly Hindu and Muslim, and of multiple cultural expressions. Then 1947, and later 1971, the year of the Liberation War of Bangladesh, saw large exoduses of people on the basis of faith and homogenisations of communal life all across Bengal. But Korim Shah was writing about the earlier time, when, for example, Hindu barinto jatragan hoito, nimontron dito amra jaitam (there would be jatragan in Hindu households and they would invite us and we—meaning, people of the other community—would go). It was a time of the cohabitation of communities, unequal and segregated for sure, but despite the repression, suppression and mutual mistrust, it was still a time of many voices. Korim Shah, Chandrabati, Sushoma—they all come out of that time.

Sushoma Das’ parents were singer-songwriters. What did they sing? I had asked her. And she drew up much the same list as Korim Shah’s, with stronger emphasis on women’s ritual songs and kirtan, as would be common in Hindu households. Her mother, Dibyamoyee, sang gopini kirtan and dhamail—songs of the women’s inner quarters. Her father Rasik Lal was a man of the outside world, he commanded a lot of respect in society, people called him ‘Talukdar’, she said. He led teams of kirtanyas; sang ghatugan too. Sushoma Das was therefore birthed into a world of music. Her younger brother Ramkanai Das later became a singer of Hindustani classical music and he travels abroad and teaches expatriates in the US, while recording classical and folk music at home. Sushoma mashima had never travelled out, however. She was married while still in school and then raised a large family, but kept up her music. When she came to Sylhet town much later in life, she sang for the radio. How did you manage to keep the music alive? I asked. She had great strength of will, Chandrabati Roy Barman answered on her behalf.

Sushoma Das & Chandrabati Roy Barman

This was our first meeting with the two women together in Chandrabati Roy Barman’s house in Topkhana, Sylhet town. The previous evening we had met Chandrabati Roy Barman and she had so charmed us that we wanted to meet her again, with this other singer she told us about, two years older than her and a ‘storehouse of songs’, according to Chandrabati mashima. About her own self she had said, I have an indomitable spirit. This she said in answer to most questions—how did you learn to sing, how was it after marriage at 13, how did you take your high school exam with your daughter, how did you balance home, children, husband and your music? She answered all these questions with a laugh and with her signature ’Amar utshaho khub beshi.’ In other words, no one can stop me.

Despite being of almost the same age, imbibing the same oral culture and having had similar struggles as women, Sushoma Das and Chandrabati Roy Barman are also very different as individual artists and their different personalities come out in their styles of singing and approach to the song, even when they are singing the same song as a duet, such as the one extracted here. It is a song from the ‘kalanka-bhanjan’ cycle of gopini kirtan, about how Krishna helped Radha prove that she was not adulterous, rather the most faithful of all women. That is the main plot, but this particular song is also about Krishna’s mother’s fears for her sick child, brimming with batsalya ras/vatsalya rasa or emotions of parenting. Interestingly, on the day of this recording, Sushoma Das was extremely anxious and restless for her grandchild in hospital, mirroring Nandarani’s anxiety, and after a few songs, she just could not stay anymore; she got up and left.

Through quite a few years of knowing the two singers, we understand now that Sushoma Das is strong and firm and more fixed on text and the melodic structure, almost pedagogic in approach; she does not have much patience for deviations. Chandrabati Roy Barman, on the other hand, explores more her artistic freedom within the form. ‘I would climb trees as a child, swim across the Surma; I was the only daughter in the family after many generations of sons, so I had a special place at home,’ she said. Her grandmother Rajweswari was a fine singer. She learned some songs from her, and then just by listening to people. As she put it: Amar utshaho khub beshi! She was propelled by her great enthusiasm for music, for life in general, and of course her enormous talent. Her son, Rana, an erstwhile theatre director, said about her (with obvious admiration and pride), ‘Ma has to be forcibly stopped at weddings where there are groups of women singing and dancing the dhamail. She does not realise that she can’t do so much anymore.’

On a personal level, we feel blessed to have recorded Chandrabati Roy Barman and Sushoma Das at this point of their lives, when their knowledge is at the fullest and their memory and voices are still intact. At the same time, I feel that it is highly significant that Chandrabati Roy Barman and Sushoma Das came to Kolkata and participated in the annual Baul Fakir Utsav, in 2010 and 2011, respectively. They brought with them an-other voice, adding more dimensions of time and space to the somewhat homogenous, though intoxicating, sound of the baul and fakiri songs which dominate the scape of the festival. Chandrabati Roy Barman and Sushoma Das are part of an orality which might still be possible in the east of Bengal but from which the west is surely divorced. Besides, even in their own region things are changing and will continue to change. From Rajweswari to Chandrabati, from Dibyamoyee to Sushoma, the flow of song was natural. It can no longer be the same as our sonic and visual worlds are constantly altered in an increasingly materialist world; even from Sushoma to her daughter Bashona, the flow is bound to be interrupted.

Written in 2011.

This recording session in Sylhet town took place in the shrine of Arkum Shah, a twentieth century folk poet who wrote mystical poetry in the Sufi and Bhakti traditions. His devotees gather in his shrine each Thursday for music and once a year to hold the poet’s Urs or anniversary, with songs and prayer.

Arkum Shah Mazar

This recording conveys the ambience of the shrine, where the act of singing becomes an act of worship. Singing and dancing together is a way of sharing faith, uttering words that everyone in the gathering knows, also sharing gestures. There are no listeners of this music, everyone is a participant. Smoke from the incense sticks fill the space of the room as the devotees go round and round the tomb of the mystic poet, cymbals come clashing on the chorus of voices, drums roll and the words become more and more indistinct. It is just a soundscape, played out at night by a group of devotees, when the rest of the town has fallen asleep.

Later one of the main keepers of the shrine, the khadem, gave us a copy of a book of Arkum Shah’s songs, bound in red velvet. I strained my ears to get the words of the songs and once I got the first line, I looked up the song in this book. They are mostly songs about biraho as a way of devotion.

Written in 2010.

Ruhitaswar Chakraborty, popularly known as Ruhi Thakur, a man who left such an indelible mark on us with his songs. Perhaps because he would be gone within a year of this recording? At the time of his death from cancer Ruhida was hardly in his mid-50s.

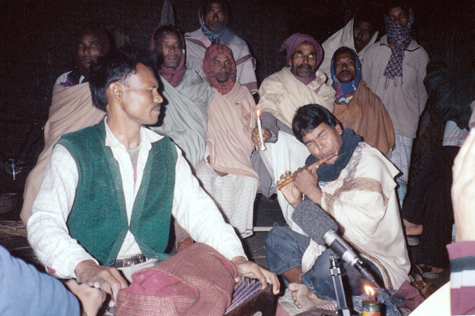

A day before this recording session we had seen him for the first time, at a meeting of bauls in Sylhet town (interestingly, baul here does not suggest any particular esoteric practice such as in Kenduli or Kushtia. But baul means those who sing mystical poetry; devotional songs, Sufi or Bhakti or both. Those who take on this singing as a way of life and also sing for a living). This was a time of political unrest and increasing fundamentalist pressures in Bangladesh and people in the practice of such music—the bauls and boyatis (these labels are also often interchangeable)—were under threat of being silenced. Ruhi Thakur, Chandan Miah, Birohi Kala Miah, Abdul Hamid and others were thus meeting to discuss how they could fight the system and continue to sing.

Ruhi Thakur & Others

Ruhi Thakur was wearing an embroidered synthetic kurta with a shine, hair up to his neck oiled and neatly combed. We had not heard him before, hence did not know what to expect. After the meeting we all went to Abdul Hamid’s home, where I had had been during my first trip alone, two years ago. This was my second visit. When Ruhi Thakur started to sing, we were speechless. Sukanta and I just exchanged glances. He sang the 19th century mystic poet Radharaman’s bichchhed or song of separation with such tenderness: Shyam kaliya shona bondhu re, ami nirole tumare pailam na (I didn’t get to be with you alone, my sweet friend, my Shyam Kaliya/I never could tell you what aches my heart).

Our second session with him was in the house of our friend and guide in Sylhet, Ambarish Dutta. Ambarishda was hosting an ashor (home concert), as he has so generously done over the years. Many of the finest folk singers of Sylhet—people we were looking to record—were present. Chandrabati Barman, the septuagenarian singer of women’s songs and bichchhed, deeply respected and loved by everyone present, was the star attraction of course. We had only just met her and were completely overwhelmed. Then there were Ruhi Thakur, Abdul Hamid Jalali, Chandan Miah and Rehana–who would belong to the broad category of ‘baul’ in Sylhet, who sing mainly in shrines and melas, in open air concerts, before of vast audiences. There were also Himangshu Biswas and Krishno, more urban and middle class, the former also a singer of Bangla art song and adhunik. The audience comprised mainly middle class professionals, who turned out to be the keenest listeners–real roshik or connoisseur. A song comes alive not only through the singing but also by listening. Amare keu chhuiyo na go sajani is an extremely popular composition of the folk poet of Sylhet, Shah Abdul Korim, who was still alive at the time, at 92. We can hear in this recording the shared pleasure of the singer and the listener. We can hear people rejoicing in the song, clapping and singing along. The living room of a banker’s apartment had transformed into the space of a mela.

The other song selected here conveys the same kind of pleasure, Surodhunir kinaray shonar nupur ranga paye. Gouranga or Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, the Glowing One, the ultimate devotee of Lord Krishna, goes singing and dancing, leading the band of devotees along the bank of the holy river of Surodhuni (Ganga). Four years later, in 2010, Ruhi Thakur’s brother, Ranesh Thakur, sang this song at our own Baul Fakir Utsav in Shaktigarh, Kolkata, when a team of musicians from Sylhet came to take part in the festival. From that video, you will get a sense of the communal spirit of such performances.

Written in 2010, edited 2020.

This audio clip is from a documentary film on people who live in the forest regions of south-western West Bengal and policies which govern their lives, for which I was asked to compose music. I decided to base the music on field recordings and so Sukanta and I went to Jahajpur village of Purulia, to the house of Naren and Chapalabala Hansda, a musician couple from the Santhal community. We had gone to their village on an earlier field trip in 2005.

Chapalabala, Jagadish & Naren

The music, though belonging to people who live within the official boundaries of ‘Bengal’, is not ‘Bengali’ in the same sense as baul or bhatiyali or kirtan is. Rather, it has contiguity with the music of the tribals of the Chottanagpur region of Jharkhand and Bihar. The instruments played are also typically tribal—the big drum or dhamsa that hangs from the neck, the bowed kendri and, the Santhali flute. This ceremonial music is also very community based—music of tree-worship, music of harvesting or of birthing and so on.

The musicians here are Naren, Chapalabala, Panchami, Shibnath and Jagadish Hansda, Anil Kisku and Ashok Hembram.

Written in 2010.

This recording session was organised by our friend and teacher Salamat Khan, a confirmed bohemian who lives in Faridpur town in the west of Bangladesh and knows the place and its people inside out. For years one of his main passions has been songs of the 19th century poet-philosopher of Kushtia, Lalon Fokir, Faridpur being not far from Kushtia.

Salamat Khan, once a medical college drop-out and later self-styled journalist, is also a member of the Faridpur Sahitya Sanskriti Unnayan Sangstha, a group that engages with local cultural activities, especially with the propagation of songs of Lalon. The men who had gathered this evening, aged presumably between 40 and 70 years, were rather sombre, all dressed in white (Salamat Khan was the sole colourful exception), and there was a certain austerity about the way they sang. It has taken me several years to understand that this austerity is characteristic of the Kushtia bauls, that they do not go for much embellishment, but present the song as text, sermon-like.

Binoy Nath

Here we have chosen a song of Lalon Fokir that Binoy Nath, the senior-most member of the group, had sung. ‘Which path will you take? If you choose to go with the guru, then you must leave behind your social obligations.’ That, roughly, is the essence of what he sang.

When we went back to Faridpur a year later, we heard that Binoy Nath was no more. We had not had the time to listen to the Faridpur recordings during this whole time, the songs lay buried under more recent recordings. For us, attentively listening to Binoy Nath and the other Faridpur bauls from this session coincided with listening to a collection of baul songs from Kushtia that the Lalon scholar, Carol Salomon (1948-2009), had recorded in Santiniketan in 1981, the centenary year of the religious studies scholar and writer, Kshtimohan Sen. It is now that the uniqueness of Binoy Nath’s singing was revealed to us.

It is our loss that we did not record him more, just as Carol Salomon’s sudden death is a great loss for baul studies. I wrote to Dr Richard Salomon, Carol’s husband, expressing my wish to present a recording of Khoda Baksh Shah song singing Lalon alongside Binoy Nath’s song and he has very kindly granted us permission to do so. I wanted to place these two recordings side by side as an instance of a style of singing Lalon that so typically belongs to Kushtia. In so doing I wanted to share with our listeners a thought that comes to me about the continuity of style in some particular (closed) communities—they seem more like communities within communities—while overwhelming changes take place elsewhere.

Written in 2011.

Related links and books:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lalon

http://www.scribd.com/doc/7253135/On-Fakir-Lalon-Shah

Allen Ginsberg reads “After Lalon”

Chakraborty, Sudhir, Bratya Lokayata Lalan, Kolkata, 1992

Jha, ShaktiNath, Fakir Lalan Shai, Calcutta: Sangbad Prakashak, 1995

Ibrahim Boyati is someone I knew from before the start of this project. I had first met him in Bangladesh in 1998, on the sets of Tareque Masud’s documentary Muktir Kotha, a film in which he was playing himself at a performance. Between Muktir Kotha and Tareque’s later film Matir Moyna (2001), two projects in which we were both involved, Ibrahim Boyati’s dotara and voice got firmly etched on my mind and when Sukanta and I started our own journey, I knew that we would have to go to his home in Faridpur for his riches. Our subsequent meetings with Ibrahim Boyati have indeed enriched us and our work.

Ibrahim Boati

Ibrahimbhai is blind. His voice is hoarse and extremely powerful; even when he speaks, you cannot but stop and listen. He was a ‘canvasser’ once, that is how he describes himself; sold herbal oils and medicines by the roadside, announcing his wares and breaking into song from time to time to attract buyers. Now he deals in stories—preaching to his audience and, again, breaking into songs to make a point. This we saw during the several recording sessions we had with him: at his home in Bhashan Char in Faridpur when he talked about his life and struggles in the 1971 War years; at Membar Gotti, a village of Faridpur, where Ibrahim was conducting milaad, leading the community through prayer and song in the dark of the night; at the home of the trader-cum-singer Sadek Ali in Uttar Shobharampur by the Kumar river, when he sang bichchhed gaan of Bijoy Sarkar, songs of Lalon, and the kahini or long narrative song of Waz Kuruni (or Owais/ Awais Qarni as he is known in other parts of the Islamic world). Our audio extract is from the kahini that he sang.

This was a day of music which started in the morning. A small group of musicians—Harun, Rafiq, Nuru Pagla and Ibrahim– had gathered in the courtyard of Sadek Ali’s house and each took his turn to sing. Ibrahimbhai sang the kahini towards the end of that session, late in the afternoon between the Asr and Maghrib prayers. It is a 40-minute long song, which Ibrahim sings playing on his dotara, while the other musicians play harmonium and tabla and sing the parts of the chorus.

As the story goes, Waz Kuruni was a devotee of Mohammad who lived around the same time as the Prophet, in a town called Karn in Yemen. The Prophet had never met the man, but knew of his deep devotion and love for him and so, at the time of his death, he had asked his two trusted disciples, Ali and Omar, to go and find the man and give him his robe, in acknowledgement of his love.

The story as narrated by Ibrahim Boyati is an elaborate one, with a main plot and several sub-plots, stories within stories , all to do with aspects of Waz Kuruni’s life and, perhaps, some other stories about other people not connected with Waz Kuruni’s life also get woven into the tale. The form of this music is fluid, there is no fixed text and it evolves with each individual performer and each particular performance. The style is part recitative, and part of it is sung. As the storytelling progresses, the audience gets drawn into the narration, becoming part of the chorus and part of the story itself. Yemen or Mecca are no longer faraway places, Awais Qarni is their very own ‘Wajja’, whose story they love to sing and hear over and over again.

Written in 2010.

Baotipara, a village of Faridpur near the town of Bhanga, was the home of the folk poet Banikanta Das and a place of kirtan. We have done fieldwork in this village many times and on this first trip, the women of Baotipara, aged probably between 20 and 45 years, sang songs of puja and wedding songs or biyar gaan. The song selected here is about the goddess Uma or Durga. ‘Where have you come from, O mother, how shall we worship you?’

Women from Baotipara

Uma Sangit is also a popular form of the eastern Bangladeshi state of Sylhet and Ritwik Ghatak has used this form in many of his films, most notably in Meghe Dhaka Tara. Sanchita Roychowdhury, a singer born and brought up in Calcutta, whose father, the legendary folk singer Ranen Roychowdhury’s house was in Sylhet, has a real passion for the music of that land and during an interview with her, she sang for us a beautiful song about Uma’s unfinished meal in her natal home, when her husband, Shib, comes to fetch her and take her back to his house in Kailash song.

Written in 2010.

For this session we had gone to the Kumar River, to record ‘bhatiyali’ in its ‘natural setting’—the famed ‘song of the boatman’ on the boat. That was the idea, but the session in turn has provoked questions about field recording and about the genre/form/musical structure(s) known as ‘bhatiyali‘. Is this really the boatman’s song or songs of a land of rivers?

Sadek Ali with Idris Majhi

The ambience of the river was added to give a certain ‘naturalness’ to some of Abbasuddin’s songs recorded for the Gramophone Company of India in the 1940s. Here in this session we have the actual beating of the water with the oars, but even this naturalness was, in a sense, created by us. The ethnomusicologist Deben Bhattacharya once wrote about his recordings, ‘Right from the start of my work as a collector, I had decided to record music in its proper milieu—a harvest song must be recorded in the open field, a wedding song in the house of celebrations, religious music in a place of worship.’ I have wondered sometimes whether when we enter the ‘proper milieu’ as outsiders, the space remains the same? Here we were rowing in a half-dead river, going round and round in circles. The sound of this recording is very special indeed, but at the same time it begs the question of whether the boatman would actually go to the river at that time of year to spontaneously break into songs? Maybe we can get the ‘proper milieu’ only after knowing a place very well, after going over and over to the same place, after building a rapport with the people by which our presence does not matter so much. At least we become familiar enough for them to ignore us. That rarely happens, but if it does then those are blessed moments for the recordist-researcher.

So far bhatiyali goes, there is another bhati region of Bengal, more to the east—the low-lying lands of Sylhet and adjoining Cachar in Assam, which remain submerged for half the year. There too there are songs called the bhatiyali, which sound different from the bhatiyali of the western parts. Is it then the geographical location that gives the form its name? Extending that logic, the musicologist Dinen Chowdhury says, anything that comes out of the bhati regions is bhatiyali. Further confusion of labels.

Written in 2010.

Related Links

SD Burman sings ‘Allah megh de’ in Guide

S.D. Burman sings ‘O re Manjhi’ in Bandini (adaptation of bhatiyali)

From the time that I had set out for Rangpur in Bangladesh, I was keen to find one singer whom I had heard on a recording made by the ethnomusicologist Deben Bhattacharya (1921-2001), who is known for his collection of songs from the gypsy trail, among other things. Deben Bhattacharya, a Bengali originally from Benaras or Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh, India, had been based in Paris for the later part of his working life but he had recorded music from around the world, published albums of field recordings, made films, produced radio documentaries, even translated and edited books of the mystical poetry of Bengal throughout his eventful and prolific career. River Songs of Bangladesh, a collection of songs from different parts of Bangladesh mainly on the theme of the river, was one of his last albums of field recordings, released by Arc Records in 2001, the same year that he passed away. The girl I was looking for was on this album, her name was Anurupa Roy, but apart from knowing that she was from Rangpur in Bangadesh, I had no other information about her.

Anurupa, Mini & Shopon

It was Bishwanath Mahanta, the music teacher of Mahiganj in Rangpur, who helped us track Anurupa. He said we would have to go to a place called Sindurmotir Bajar in Lalmonirhat and there we could meet Shopon Das, a dotara player, who would take us to Anurupa’s house. Our guide Ershad, an NGO worker, took us to Sindurmoti where we met Shopon and he said he would come with us.

Sindurmoti, a place with a legend. has a little temple by the side of a pond dedicated to Sindur and Moti, two daughters of a king, Raj Narayan, who had sacrificed their lives to bring water to the people. Perhaps the little girls had drowned in this pond? The idols hold their hands upwards, unusually long fingers pointing to the sky. There is a Sindurmotir mela they have here at the end of spring, in the Bengali month of Chaitra, in first half of April. In these parts of Bangladesh I found the Hindu presence quite palpable, more than in some of the other regions where we have been. Sindurmoti and Debicharan (Anurupa’s village, where we were going now) certainly appeared to be majority Hindu.

Before we reached Debicharan, late in the afternoon, two other singers had got into the car—Mini Roy and Bipin Chandra Roy. And there was one other, Manik Roy, who joined after we reached. Following the initial surprise at our visit and explanations, we had a lovely recording session with these young musicians, manily of bhaoaiya, in the courtyard of Anurupa’s house, surrounded by her relatives and friends. Anurupa, Mini, Shopon, Bipin, Manik, hardly 18-22 years old, were like a team, supporting one another. ‘Bipinda is very quiet but you must ask him to sing.’ ‘Manik also writes songs, you know.‘ ‘It’s her turn now.’ ‘No, it’s hers.’ They all seemed generally very happy to have this impromptu concert, more because we had gone from Kolkata, the big, elusive city of Bengal. The city has its own attraction, especially to them, it must have more of a name.

Shopon played the dotara with everyone, and the bridge kept falling. But he had such a beautiful sound that we also asked him to play solo. Anurupa and MIni sang a few wedding songs on my request. They said they did not know the repertoire too well, but there was a woman who knew many songs and next time we went, they would take us to her.

Anurupa hadn’t heard about the album River Songs of Bangladesh, which had taken us to them. ‘Was there an album? I thought they were recording for the TV.’ I said, yes, the album was released in England. Said, I’d make her a copy from mine and send. She remembered going with someone to Dhaka and recording in a hotel room. She was very young then, 16 perhaps. Her voice made me think about Nirmala Roy’s daughter, Tumpa. Something about this region that brings out this tone.

I hope Anurupa got the CD I tried to send to her later through our Rangpur guide. When we go again for the promised wedding songs, I’ll find out. Shopon told me on the phone that Anurupa is married now.

Written in 2010.

Bishwanath Mahanta, the music teacher from Mahiganj in Rangpur, whom we had met in 2006, passed away on 2 March 2020. As I have contact now through Facebook with one of the Rangpur girls we met on that trip, she gave me the news of his death. We have often thought of going back to Rangpur, just to see how the young musicians we had recorded all those years ago were doing now. Then we would meet the teacher too. But time is always in short supply and there is always so much to do that so much just does not get done. And now, Time, like the bird, has flown away.

একবার ফাক্কাও করিয়া, ময়না যাবে উড়িয়া…

Bishwanath Mahanta and Moushumi

Here we are adding an extract from our conversation with Bishwanath Mahanta. It feels strange now to listen to his story about so easily crossing the border to go to a wedding on the other side, giving a small tip to the guards.

People like Bishwanath Mahanta are great storehouses of local knowledge, essentially living archives; when they are gone, there is a hole that cannot be filled with anything. Not with any travelling archive, not with any recording stored in some Cloud somewhere.

Bishwanath Mahanta singing

Bishwanath Mahanta was a music teacher of Rangpur in the north of Bangladesh and what he taught was primarily a body of song called bhaoaiya. During this recording session, which was more like a lecture-demonstration, he talked about bhaoaiya being the music of the region and, using the harmonium for accompaniment, explained its many variations and styles. He talked about Coochbehar across the international border—it is the same region, he said. There are artists who cross the border to come and give concerts in Rangpur, Ayesha Sarkar being a local favourite.

Many of Biswanath’s students had become ‘successful’ bhaoaiya singers. ‘Successful’ of course only in their small-town or regional context—they sang for the radio and some had CDs in the market and they also performed at local events. Not Digen Roy, who is featured in this session along with his teacher. We had met him the previous evening at a recording session in Barobari, also in Rangpur. He seemed different from the rest of the singers, and so we asked him to join the session with his teacher the next morning. ‘Digen is very good but somehow lacks confidence,’ Bishwanath Mahanta said. ‘I have to send word to him through other people to come and see me.‘ Digen sold paan in the local market (maybe that is what he still does). There seemed to be a special bond between this shy and quiet student and his teacher.

Bishwanath and Digen

When I told Sukanta about his passing. he reminded me of the story of the egg that Digen had told us. Bishwanath, like a caring parent, would feed Digen an egg, first thing before starting lessons, for a bit of extra nourishment. Digen was so touched by this act of kindness, that he had to mention this while talking about his teacher. You can feel that parental touch in the way he passes on his song to Digen in the recording that we have uploaded here.

Digen Roy

Mao boro dhon shona re, Bishwanath sang; a verse in praise of the mother. Then he nudged Digen. ‘Kao,’ he said. Say it. Mayer maya shital chhaya; she shades you with her love, Digen continued. You hear a sad strain his voice. With his parent gone now, Digen’s vioce must sound sadder.

Written by Moushumi in 2010, revised on 28 April 2020.

Musurabala is a nachni (woman singer-dancer-entertainer) from Purulia. The nachnis live outside mainstream society and do not enjoy rights that ordinary women in domestic settings do, although there is increased awareness about rights nowadays. Barring a few exceptions they don’t enjoy respect as the artist either. Sindhubala Devi (died 2004), a nachni, was the first to get recognition as an artist from the state by way of the Lalan Puraskar of the West Bengal government in 1993. Her music is archived at the National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA) in Mumbai. There are others: Malabati, Parbati—the successful ones. But Musurabala enjoys no such privilege.

Musurbala

In our audio selection Musura sings a jhumur. The authorship of this song is contested; Musura’s song, about the courtship of Radha and Krishna, bears the name of the folk poet Gourangia Singh, but later Amulya Kumar, senior jhumuria, gave me another version of the song, with the name of Binondia Singh as the author saying Musura had got it wrong. However, in these fluid conditions of singing and songmaking, often it is difficult for the outsider to know who is right and who is wrong.

This recording session took place in Musurabala’s separate quarters in the house of her rasik, Amrit Mahato. His wife and children lived in the main house. This was Chitarpur village in Kotshila, close to the Jharkhand border. An extremely dry and rugged land, where the songs too seem parched, with no trace of sentimentality. Amulya Kumar, who had gone with us on this trip, played the harmonium and sang with Musura, while she danced; her rasik played different drums—madol, table and saran.

The session was mediated by theatre activist of Purulia, Bishwanath Dasgupta, Bishu. We owe him our first lessons on the music of Purulia.

Written in 2010.

Sudheer Palsane and I went to Rahima Kolita’s house in Krishnai, Goalpara, in Assam on our way back from Cachar, also in Assam, in the monsoon of 2005. It was our last-but-one stop at the end of a long journey of about 15 days. We had a taken a bus from Guwahati early in the morning and got down at Krishnai, a small town, at about 10 a.m. We asked people for directions to Rahima and Madhab Kolita’s house, and were shown the way. I had heard of them from Chandan Paul of Coochbehar. He said two things about Rahima. Firstly, it was music that had brought about this radical marriage of a Muslim woman with a Hindu man. Secondly, he said that since the death of the famous singer of Goalparia songs, Pratima Barua, in 2003, Rahima has been considered one of the best exponents of this music.

We talked that day about many things: from their music and marriage to religion, regional politics, the music industry, continuity and change in tradition and of course the iconic place of Pratima Barua in Goalparia geet.

During the last three decades, the Bengali urban listener’s introduction to songs of Goalpara has been through the voice of Pratima Barua song—perhaps such a statement will not be too far from the truth. Indeed, in the 1970s and 80s, it was that one seductive song of Pratima Barua, plucked from a vast and varied repertoire of Goalparia songs, that hit the market—geile ki ashiben mor mahut bondhure. Where this song came from, few people knew, but most Bengali listeners in towns and cities would have heard it. Where do Goalparia songs belong, to Bengal or to Assam? Also, what is this form of music—is it a kind of bhaoaiya with distinctive regional characteristics, a form within a form, or is it an independent folk form? The matters of musical contiguity and linguistic and regional variations within forms and the act of naming forms, are all extremely complex. The famous musicologist, composer and singer from Assam, Bhupen Hazarika, had said in a documentary film on Pratima Barua that the Goalparia language stands somewhere between Assamese and Bengali. Not only linguistically, musicologically too perhaps. And maybe Pratima Barua too had this duality/split in her.

Rahima Kolita with Moushumi

She lived in Gouripur, in Assam, quite near Cooch Behar in north Bengal; also not far from Dhuburi in Assam. She was celebrated as Bengal’s own, especially by Bengal’s intellectuals, while she regularly performed on All India Roadio’s Guwahati (Assam) station and recorded many albums there. Rahima Kolita’s position is less ambiguous, she is known more in Assam than in Bengal, and she surely has a style of her own, quite distinctively different from Pratima’s. Yet it seemed that she too could not help measuring herself against the baido/didi (elder sister), for it was this Pratima didi who had taken Goalparia songs beyond the regional boundaries of Assam and north Bengal to a wider and discerning audience, and had thus set a kind of ‘standard’ for this music. So much so, that when In 1998, a young student of anthropology from France (Annu Jalais, now an important anthropologist of the Sunderbans) wanted to write her MA dissertation on bhaoaiya, she was directed to Pratima Barua’s house—Matiabag, the royal palace of Gouripur, situated on the bank of the river Gadadhar. And it was at in the course of her interview with Annu that this highly charismatic singer had declared, ‘My name is Pratima Barua. If I must give my life for these folk songs of Goalpara, then I will do so.’

Rahima and Madhab too clearly give their life to this music, but they sing in a different time, from a different social location, for a different audience. Their music is less intellectual and more verging on the popular, although at its base is the same traditional music of Goalpara. They gifted me their recent Bollywood-style music-video, Moner Aayna, which would be a sharp contrast to anything Pratima Barua ever sang. Here in this interview though Rahima is not performing, she just talks and sings at ease, in her own home, in between giving us food and tea and paan. In this clip, edited from footage shot by Sudheer, Rahima talks about learning to sing in the midst of extreme poverty, her father’s absolute joy in her musical achievements and the joy she herself derived from singing.

Written in 2011.

Related books

Barua, Nihar, Prantobashir Jhuli: Goalparar Lokjiban O Gaan (Bengali). Kolkata: Stree, 2000.

Datta, Birendranath, A Study of the Folk Culture of the Goalpara Region of Assam. Guwahati: University Publication Department, Gauhati University, 1995.

Video recording by Sudheer Palsane of women performing rituals on the occasion of Janmashtami or the birth of Krishna, at Chandrapur village in Cachar, Assam. Although situated in Assam, this region, which is contiguous with eastern Bangladesh, is primarily Bengali-speaking, Song and dance are a part of this ritualistic worship of Krishna. The principal singer was Reba Nashkar and Chandrapur was her natal home, as it was for most of the participating women. They were village girls married within the village or outside but who returned to their parents’ homes every year at the time of this festival in the Bengali month of Bhadro (August-September). Some would also be married in Chandrapur. Reba Nashkar said she had first learned these songs and rituals from her mother.

Reba Nashkar talks about the rituals

Shubho Prasad Nandi Majumdar, singer and college lecturer, was our local guide in Cachar during this trip.

Written in 2010.

His singing reminds us of Hemango Biswas’ Bhatiyali.

Barindra singing

The senior baul singer, Fulmala, was passing by our room in Kenduli when Debdas Baul’s youngest son, Uttam, saw her and invited her in. She stopped for this short interview and a couple of songs, recorded on camera by Sudheer Palsane. Fulmala said, ‘Those days when I could really sing are gone’. Even though she had aged and had recently suffered a stroke, she still carried signs of a strong personality.

Fulmala had grown up in Faridpur in Bangladesh and she came to India with her husband, a kirtan singer, after Partition. From then on she had had a life as a singer, mostly in the company of the bauls of Birbhum, singing on trains and at melas.

Fulmala Dasi

We met Fulmala again after almost five years, in 2009, at Bolpur station and she looked frail and shrunken, as though she could do with a bit of looking after now. She was with Gautam, Debdas Baul’s second son (with whose family she lived now), and they were going to board the same train as us. We got onto the train and stood together at one end of the compartment. Fulmala first sang a song, then Gautam, their voices now drowning, now surfacing with the motion of the train. Gautam Das Baul, young and gentle and a little bit shy perhaps, seemed like a not-too-keen busker. It is so noisy, he said before starting. Fulmala was more resilient even now. ‘Once my voice would carry to the other end of the compartment,’ she said. Then they got off at Gushkara station, to take a train back to Bolpur.

At Kenduli, Fulmala had sung a song about the faith-train. It takes you to the end of this life on earth, and beyond, she sang.

Written in 2010.

Ashalata was magical on stage, performing the birth of Krishna through song, narration and dance. Now she was Basudeb, Krishna’s father, now Kangsha, his wicked uncle, now Jashoda, his adoptive mother. Her team of musicians, including her brother and her husband, both khol players, supported her as she made this mythological tale come alive for the large audience that sat spread on the floor of the tent in Kenduli where she was performing kirtan.

Kenduli, by the river Ajay, associated with the 12th century Sanskrit poet Jayadev (or Joydeb, as we would say in Bengali), becomes the meeting place of poets, singers and devotee-listeners every year at the time of Makar Sankranti or the end of Bengali winter month of Poush, which coincides with 14-15 January. The place is believed by many to have been the birthplace of the poet, although historically the fact is now disputed claiming Kenduli Sasan in Orissa to have been Joydeb’s actual birthplace. Makar Sankranti is the time of the famous Kenduli or Joydeb Mela of Birbhum (the place is also called Joydeb), which is a fair held in the name of the poet, and to which singers and poets, mainly bauls and kirtanias have been coming for hundreds of years. The Dutch ethnomusicologist Arnold Bake had filmed baul musicians and Ajay bathers at Kenduli in 1932-33; the crowds then were obviously thinner, but the main reasons for coming to the fair were probably the same—to bathe in the waters of the blessed Ajay, then offer puja at the centuries-old terracotta temple of Radha-Binod and to listen to music. There are of course the other more mundane reasons for going to a fair—to buy important household goods, from pots and pans to fishing nets, and to have fun.

Radha-Binod Mandir, the centuries-old terracotta temple at Kenduli

While Bake was capturing an age-old tradition with new tools, he was at the same time also pioneering a trend of recording Kenduli and such other melas on camera. Many filmmakers have since been visiting Joydeb and recording their impressions of the place. Interestingly, the main attraction for most urban travellers to this festival seems to be the baulgaan that happens there. Kirtan has come less into focus (although Bake recorded both baul and kirtan at the mela), not just in films, but even in fiction and non-fictional writings about Kenduli. Interesting anomaly, if we remember that the saint-poet Jayadeva has been venerated down the ages for his Gita Govinda or Songs of Govinda or Krishna, sung as kirtan.

But at Joydeb you also see how kirtan, the form, has been adapting itself to changing times, incorporating styles of TV drama, with costume and synthesised instrumentation. And you can hear lines from popular film music creeping into the compositions. This is very different from the kirtan we heard later in our fieldwork at Baotipara or Sadhuree in Bangladesh, where an older time seems to prevail. Ashalata Mondal’s performance had all these new features, but doubtless she was a brilliant performer. And I think that what the kirtaniyas retain despite all the change that is coming in, is faith. They sing in faith and this 18-20-year old woman, just married and very much in love with her performer husband, also seemed to have that faith. She sang believing the words of her songs.

After the session was over, Ashalata came to our room on the mela grounds with her mother and the rest of the troupe for this conversation which Sudheer Palsane recorded on camera. She seemed as much at ease here as she had been on stage, and even while talking, when she broke into song, she seemed to unconsciously return to the stage, playing Radha, imploring Krishna to wake up at the end of a night of music, dance and love, for she would have to return to her everyday life of domesticity now.

Written in 2010.

This video was shot by Sudheer Palsane and the audio recording was made by Sukanta at the home of Golam Shah, a fakir from Shaspur in Birbhum. Golam Shah was a little over 60 years, but he looked much older, more so because he had not been keeping well. He had been hospitalised a few times in the recent past, it was probably a heart condition, I don’t really know. Besides, I think that age comes differently to people in different circumstances. When Sukanta and I had gone to his home with Debdas Baul in September 2004, and when he took out his violin and tried to tune the old strings and they kept breaking, I did have a feeling that we were running out of time.

Below is a photo from that session and I have also posted a song we recorded that day. It sounds very familiar, very much like some songs from Bollywood; ‘Bahut pyar karte hain tumko sanam’ comes to mind. Yet the song shows the two-way journey of folk and film songs, of how one influences, and goes into the making of, the other. This sounds like Bollywood, indeed; but where does Bollywood get its songs from? The 1991 Saajan song takes us back to an older Mehedi Hassan song from Pakistan, ‘Bohat khubsurat hai mera sanam’. Small wonder, therefore, that a much-travelled tune like this one should take the form of a Bangla fokiri song; Islam too has journeyed over so many lands, through so many centuries, to reach the eastern ‘frontier’ of Bengal.I am never quite sure what name to call these songs. When sung together in communal gatherings in shrines, they can sound like Bangla versions of North Indian qawwali, but here there are just two singers singing and it sounds more like an individual’s prayer. The Fakir’s prayer, hence a Fakiri song.Serious scholars of form might not agree.

Golam Shah with his sons

Some years ago I had read an autobiographical note by Golam Shah, published in a collection of essays and conversations with bauls and fakirs and scholars of this music. In it Golam Shah had talked about his life as a singer of fakiri songs, about learning to sing from his master Muhammad Shah and about travelling with songs. What had struck me then as it struck me again now was that Golam Shah seemed to have no complaints at all—not against the stark poverty that surrounded him, or against their marginalisation as singers of baul and fakiri songs in an environment of increasing religious fundamentalism and intolerance.

This is one session that touched us very deeply, for the way everything unravelled on that day. The excitement with which Golam Shah fixed new strings on his violin; the way he said to his sons Salam and Jamir that they should give us their best and the way his sons had actually dressed in their best for the occasion; the way Golam Shah began a song and how, when his voice or memory started to fail, Salam gently gave him support, never surpassing him though; the way Golam Shah posed for photographs with his family saying, ‘Take what you like, this is your last chance.’ A big crowd had gathered in his house that day. Here was a man little known to the outside world, yet special in his own place, who commanded deep love and respect of his family and friends for the life of songs and words of comfort he had given to them.

Golam Shah passed away four months after this recording session.

Written in 2010; revised in 2020.

This recording session took place in Bhaddi village in Joypur, Purulia. Sudheer Palsane recorded the session on his DV camera, Sukanta Majumdar made audio recordings of the session. The session was mediated by Biswanath Dasgupta, a local theatre activist and organiser of a spring folk festival in the region, Palashmela. The featured artist is Amulya Kumar, senior jhumur artist, who is himself a living archive of jhumur songs. He sings playing the harmonium, Abinash Kalindi plays the dhol. Later in the session Amulya Kumar’s younger son, Hari Kumar sang a few songs.

Amulya Kumar

Written in 2010.

Rajghat tea estate in Srimangal, near Sylhet. Tareque Masud had sent me here with Shah Alom Boyati. They had recorded these tea gardens labourers for a feature film, Ontorjatra. During the shoot, they had heard this music in the middle of the night.

These are songs which tell the story of a journey made long ago, from a distant land to which these people will never return. In fact, the singers, Ranjit and Tamseng, were not even sure where their original home was. Local people call them Uriya, perhaps their forefathers had come as indentured labour from somewhere in Orissa in the middle to late twentieth century. Ironically while these labourers have lost the name of their original homeland, this music has survived in the land of exile as a link to the past. They call their language jongli bhasha or savage tongue–strange name by which to call one’s mother tongue.

Tea Garden Singers

This field trip was too short to explore all these stories of amnesia and remembrance. I hastily recorded a few songs and took a few pictures. Later, when people heard the music, some recognised the melody as being Nagpuri, or coming from the Chhotonagpur belt of eastern India. This particular song is about the girl’s journey from her natal home to her husband’s house. Ranjit and Tamseng sang other songs too on the same theme of exile.

Unlike chutney music or the blues, songs which come out of other (often forced) journeys of people, these songs of the tea gardens workers of Bengal and Assam have not had the chance to grow into a body of music, but has mostly remained confined to the community. Some of these songs have been picked up by trade unionists and cultural activists exploring labourers’ lives and music, such as the singer and song collector Kali Das Gupta did with songs like Chol mini Assam jabo song or Relgadi kaisa na sundar song

Written in 2010.

This was my first trip to Sylhet, escorted by Shah Alom Boyati. Boyatibhai took me to the shrine of Hazrat Shah Jalal, where we met Abdul Hamid ‘Jalali’. Then we went to Hamidbhai’s house in Sylhet town. Abdul Hamid, originally from Bogura in the north of Bangladesh, is a singer-composer of murshidi, bichchhed and Bangla qawwali and his life revolves around the shrine of Shah Jalal. His wife, Milon, is also a composer and his adopted son Wasim plays the dotara; he is a radio artist. Hamidbhai mainly sang his own compositions as well as compositions of old folk poets of Sylhet, Shah Abdul Korim and Durbin Shah. He was joined in the music by his family and disciples.Some of Hamid’s compositions deal with contemporary political events, which is an interesting feature of his work. Then his wife and daughters sang wedding songs. There was a festive spirit about that evening and Milon said later, this has been our own New Year eve party (even though there were four days to go).

Abdul Hamid & Others

In these past six years Hamidbhai and his family have been struck by many tragedies. His teenage daughter, who was one of the wedding song singers during this session, died during an uncomplicated appendix operation in 2008. Hamidbhai himself has had a stroke and the last time I met him in 2009, his speech was slurred. This time it was he who had come to listen to me because I was performing at a concert in Sylhet. He came back stage at the end of the show. This once extremely powerful singer looked so broken that it was hard to stand before him.

Written in 2010.

Ali Akbar, a young folk singer from Kushtia, arrived at the home of my filmmaker friends Tareque and Catherine Masud, in Dhaka on this December night when I was staying with them. He had come to the capital to take part in some cultural event. The folk music collector, singer and radio and TV producer, Mustafa Zaman Abbasi, son of the famous singer Abbasuddin, often summoned him to Dhaka for performances.

Ali Akbar appeared self-absorbed, even temperamental, and when Tareque requested him to sing, he said he wasn’t feeling good about his voice. Moreover, he showed his displeasure with the harmonium that was there in the house. Bellowing with his left hand, as he ran his right-hand fingers over the reeds, they kept getting stuck, causing the singer some frustration. I understood the importance of the harmonium once he started to sing.

Ali Akbar

Ali Akbar sang two compositions of the famous twentieth century bichchhed composer and kobiyal (singer of kobigan or narrative-argumentative song), Bijoy Sarkar and one of Bijoy Sarkar’s disciples, Rasik Sarkar. His style of singing was highly ornamental, verging on the semi-classical. The harmonium plays an important role in this style of singing, adding embellishment to the vocal line, filling each and every gap with clusters of notes. Bijoy Sarkar’s bichchhed gaan or his songs of separation have an intensity about them, whoever the singer might be. To this was added Ali Akbar’s own intensity. He sounded almost like the urban singer of baithaki gaan (songs of nineteenth century Kolkata in which Bengali folk, kirtan and north Indian classical styles come together), despite his rural diction. Ali Akbar was also not happy to sing without the dhol and so he stopped at just three songs and left.

Interestingly, a year and a half later, we met a very different Ali Akbar in his village home in Dakshin Bhabainpur, surrounded by family, friends and other musicians. That evening him and his friends had put up a real show for us and there were people all around who had come to listen, filling up his courtyard, even perched on branches of trees. Ali Akbar played the dotara and danced as he sang songs of Bijoy Sarkar and Lalon—two composers from neighbouring regions of now western Bangladesh, with distinctly different styles of composition. Ali Akbar, however, presented them as his own, with his own ornamentations. This, despite living in Kushtia where Lalon Fokir’s shrine is and from where austere styles such as Binoy Nath’s (whom we recorded in Faridpur) or Khoda Baksh Shah song’ (recorded by Carol Salomon in Santiniketan) have emerged.

Written in 2010.

Monjila is a singer of bichchhed gaan and pala gaan who lives in Dhaka. I met her through the Bangladeshi filmmaker, my friend, Tareque Masud; she had played herself in his and Catherine Masud’s documentary on the oral history of the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, Muktir Kotha (Words of Freedom, 1999) for which I had also composed a song, and her provocative and fearless comments on gender and social inequality were in circulation among our friends in Dhaka. Later, with Tareque’s feature Matir Moyna (The Clay Bird, 2002), we came together again on the same project, but met only two years later.

Street Corner, Dhaka, Bangladesh

This session took place in Tareque’s office in Dhaka. It was my first trip to Dhaka for fieldwork. Shah Alom Boyati, or Boyatibhai as we all call him, folk singer and actor who has been a very supportive guide in the first phase of my Bangladesh work, had made arrangements for this session. But it had turned out to be a rather heavy day with the Kushtia baul Bolai Shah debating with Pagla Bablu of Faridpur, who is a popular folk singer, about whether or not this music should be recorded. Bolai Shah said he would sing but I could not record, because truths held in his songs demanded a certain commitment and preparation on the part of the listener and such knowledge could not be freely imparted to any or everyone. Pagla Bablu had no problems with the recording. Ebadat, Bolai Shah’s gurubhai (disciple of the same guru), remained silent. I started to feel like an intruder and kept switching off my recorder and turning it on, depending on who was singing. When it came to Ebadat’s turn and I was about to stop the recording, he said he’d like to be recorded. All in all, the day had been stressful and I was regretting that Sukanta was not there with me.

Monjila and Nazrul

When Monjila came with the dhol player Nazrul later in the afternoon, it was a great relief for me. She filled the room with her energy. She sang a couple of songs, among them this composition of the rebel poet-singer from Dhaka region, Mataal Rajjak, and there was something of his rebellion and sarcasm reflected in her voice too.

Later Monjila and I went into another room in the office for a conversation and she told me about the many seductions of music and her continuous battles to keep her art alive, despite barriers on all sides—home, husband, the music market, male singers and so on. A line she repeated many times during the conversation was, Ami to shilpi (I am an artist after all).

Written in 2010.

Changrabandha, is a small town in the India-Bangladesh border in Coochbehar district of North Bengal, where we went to record some bhaoaiya musicians. Abhay Roy, one of the main singers of this session and a health department employee, lived here and the session was organised by our local guides in Coochbehar, Chandan Paul and Amulya Debnath, who often assist media, researchers and filmmakers visiting the region for its music. Chandan Paul’s father was Harish Paul, a man who was instrumental in the production of some of the earliest gramophone records of the folk music of North Bengal. Harish Paul had a dealership of the Phillips company and was also passionate about folk music and folklore. From the 1940s he began to gather folk musicians from around different parts of Coochbehar and take them to the Gramophone Company of India’s studio in Calcutta and get them recorded under his music directorship.

Bhaoaiya session. Abhay Roy is playing dotara.

Those days of glory are long gone, the family business has split up and there are now few occasions to remember the contribution of Harish Paul had made towards the spread of bhaoaiya and chatka songs and the folklore of Coochbehar, taking them beyond the region’s territories, except when reminded by his son, Chandan Paul song . Two days prior to this recording session, on 14 December 2004, we had taken a portable mono record player to Chandan Paul’s house to listen to some of his father’s old and dusty vinyl records. That is what Chandanda had said to me when I first met him July 2004; that I would have to bring my own turntable if I wanted to listen to his father’s collection, as there was no record player in the house.

Harish Paul had an eye for fine and interesting things and when his son opened the trunk to show us his collection, there was, among other things, also an old German pen, an empty lager bottle from more than 150 years ago, some pieces of matrix or master copies of records printed on one side, even old records released by the Columbia Phonograph Company in New York in the year 1901. Chandan Paul played for us a 78-rpm record of Nayeb Ali Tepu song, a master singer of bhaoaiya songs who lived between 1916 and 1961 in Choukashi Balarampur in Coochbehar, near the native village of the renowned singer Abbasuddin (who emigrated to Dhaka after the Partition of India). It was Harish Paul who had introduced Tepu to HMV.

Chandan Paul seems to carry the mantle of his father, even if only symbolically. The regional expert, involved in creating a specialist list for a record company in a newly independent country, has lost his exclusivity today. Yet, Chandan Paul assumed the role of music director at this recording session in Changrabandha, instructing the sisters Shikha and Nita Roy from Bhetaguri, Anjana Roy from Coochbehar and Abhay Roy of Changrabandha on repertoire and style, auditioning Shanti Roy Sarkar from Helpakuri, telling the flute when to play and the dhol when to stop, testing Sukanta’s recording and going for the ‘final take’. The border town’s primary health centre where the session was taking place was transformed into a veritable studio.

Abhay Roy’s bhaoaiya, which illustrates this session, has that feel of the studio about it. It sounds well rehearsed and quite flawless—not something we’d usually expect from a field recording. Abhay accompanies himself on the dotara, Malay Kinnor plays the dhol, Dinanath Adhikari the flute, Amulya Debnath the mandira.

Written in 2010.

I had heard about the singer Debdas Baul’s long association with researchers and filmmakers, especially Bhaskar Bhattacharya (who passed away in 2006), and I was told he understood the ‘outsider’s’ needs very well. Rangan Momen had said: You must meet Debuda, he will know where to take you. During these last six years, Debdasda has been our best teacher in Birbhum, generously giving to us what we asked for, guiding us along the road.

For this recording session, our first with him, Debdas Baul came in the morning to our room in the university guest house in Santiniketan. ‘We are thinking of songs within the baul repertoire of Birbhum where the sense of biraho is expressed,’ I had told him the previous day. He came with two senior women singers, Nandarani and Dasi (Gitarani). The three of them—all probably in their early to mid-50s—took turns to sing, also accompanying each other, and the session lasted about two hours. Dasi sang with her ektara and Debdas Baul played the dugi. Nandarani, wrapped in a dark brown shawl, sat quietly listening.

Sukanta recording Nandarani, Dasi & Debdas Baul

There was a stillness about Nandarani, in the way she sang, playing just the kartal. A private communion as if, with god. She sang several songs, mainly of bhakti or devotion in love. Amar Krishno naamer posha pakhi ure giyechhe. Krishno, my caged bird, has flown away. Perched on the branch of the tree, he calls out to Radha by her name.’ She reminded me of Radharani, Purna Das Baul’s sister, in Georges Luneau’s film, singing ‘Jodi eshe thako Hari, Niye namer tori,/ Amare niyo par koriya.’ Old compositions which do not carry the signature of the composer. Nandarani had that same gesture of self-effacement.

If Nandarani is someone who tucks herself into a private corner, Debdas Baul lets the world into his own space. His home is in Suripara, Bolpur, but he is a man of the world. He has travelled widely and worked with people like Deben Bhattacharya and Georges Luneau, Andrei Jewell, Sam Mills and William Dalrymple, yet his everyday life revolves around Bolpur station, where he sits smoking ganja and talking with his friends who are regulars there. From the jhalmuriwallah to the ticket collector, to other bauls and the tea and coffee vendor. Then someone from the bigger city will alight from a train and introduce himself—someone like us, who needs to be guided into this world of music.

On this day Debdas Baul plucked on his ektara and sang texts of some of the older poets of Birbhum—Nilkantha Mukherjee, Satish Mukherjee, Jadubindu, Radhashyam Das, Fatik Gonsai—most of whom are mentioned in Upendranath Bhattacharya’s authoritative work on the bauls of Bengal. Here is a clip from a composition by Fatik Gonsai. Debdas Baul’s style of singing is stark, with almost no embellishment, as if for him it is more important to deliver the message in the song than sing to entertain.

Written in 2010.

This was my second field trip with Sukanta. The first one had also been to the temple town of Tarapith for the songs of the blind singer, Kanai Das Baul, but the session had got washed by rain, so we had decided to return the following week.

My familiarity with the music of Kanai Das Baul or Kanai Baba, as many call him, went back several years; he had sung in Anup Singh’s docu-fictional essay on Ritwik Ghatak, Ekti Nodir Naam (The Name of a River) and I had seen him during that recording session. The blind Kanai Baba was also the subject of Ranjan Palit’s film Abak Jaye Here, besides being one of the main singers in Georges Luneau’s landmark film on the bauls, Le Chant des Fous.

Kanai Das Baul