SALAMOT KHAN: THE MAN WHO MADE PICKLE

Salamot Khan, who was Salamotbhai to us and was our friend and teacher, lived and died a ‘local man’ in Faridpur, in western Bangladesh in August 2015. Since his death, Faridpur, the place which gave to us some of the best of our songs–Ibrahim Boyati and Habib, Laila and Nuru Pagla, Jainuddin’s jari and Sadek Ali’s bichchhed, Gosai Das’ kirtan, Ajmal’s Lalon, the broken voice of Idris Majhi and so much more—that place seems to have ‘died’ for us. Strange it is; so many of our richest sounds came out of that one place, and yet with one man gone, it becomes clear to us that he was the river through whose body all that music flowed. What happens when such a river stops flowing?

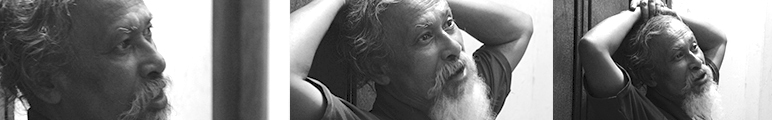

I do not know many personal details about Salamotbhai. Very few of the people he hung out with in Faridpur knew. He gave away very little, let almost no one into his private space. And that itself was the enigma—a man always out on the street, a man seemingly so public, was in fact totally and fiercely private and forever guarding his privacy! Sometimes you thought there were things Salamotbhai needed to hide. People said Salamot Khan was 58 when he died. So that would make his year of birth 1957? It is hard to know. There was a quality of agelessness about him. Sometimes he seemed childlike, and sometimes very old—as if he was always there, from before his own time. Which is why his death, about which we are more certain than his birth, for there were ‘witnesses’ in his Faridpur hospital on that morning of 12 August 2015—even that seems to elude us.

What name to call Salamot bhai’s passing?

Salamot Khan 1957(?) – 2015

Salamot Khan 1957(?) – 2015

On 11 September 2015, a month after Salamotbhai was gone, we were to go to Faridpur. The night before I wrote this: ‘Salamot bhai . . . was so essential to our world, yet so much like a bird impossible to catch. Forever uncaged and uncageable. His death to us is like the last visible flight which he has taken. As if he had a sharp beak with which he pierced the sky and once he went in, the sky closed itself upon us. We lesser mortals were left below looking skywards, our hearts filled with longing for a little bit more.’

The bird and the cage had to be the obvious metaphors for Salamot Khan, a man who lived in the world of Lalon’s songs. What is interesting is that these songs were living things for him and a part of his everyday life, while also being a deep well from which he drew inspiration for life and instructions about how to live that life. He could place these songs alongside all the other contradictions and complexities of life. And he was not exclusive in this practice. He would often say this about Lalon’s land of Kushtia: ‘People just know his songs there, they sing as they go about their daily chores of planting and watering the crops in their fields; or as they are melting hot iron in the forge. They do not need to create a special place or time for the songs, the songs are a part of their lives.’

একটি ‘পূর্ণাঙ্গ’ জীবনদর্শন

Habib sings a Behal Shah song and Salamotbhai gets into a discussion about the song and the baul ‘way of life’. 2013.

Salamotbhai sings and Nazrul Fakir of Kushtia listens. Faridpur, August 2014

Salamotbhai sings and Nazrul Fakir of Kushtia listens. Faridpur, August 2014

He would tell us about this blacksmith in Kushtia who sang ‘Lalon’s soft songs while taming the hard, hot iron in the fire,’ he said. He had a way of talking. ‘কুষ্টিয়ায় পবনমামা ছিল কামার। লালন সাঁই-এর নরম গান তপ্ত লোহাকে সাইজ করতে করতে ক্যামনে গাইত? সারাক্ষণ গান করতো।’ Whether or not things happened this way in Kushtia, it was a beautiful story. This was surely true of Salamotbhai himself, for he could hold in his life, with ease and grace, the songs of Lalon and other mystic poets of his region, but the songs breathed quietly, never making any overt show of their presence. Salamotbhai was one of those mythical people who could go about his daily business of planting and watering and welding while singing ‘সময় গেলে সাধন হবে না/Once the moment [of doing] passes, your life will remain undone.’ He was a fabulous cook and whenever we went to Faridpur, he would bring to us tiffin boxes full of food. What he cooked seemed like his invention—the silverest fishes I have ever seen, cooked with a touch of green, or meat with layers of onion, the last layer added a few minutes before taking the pot down from the fire (I would ask him for recipes and he would teach me; sometimes I would put the pot on the stove and call him from my kitchen in Calcutta). Salamotbhai had strange ways of connecting with people and food was one of them. This I saw whenever we went to Faridpur—he would make various phone calls and ask for this and that to be made or brought especially for us, who those people were on the other side of the telephone following his instructions, we did not know. This story lived on after his death for it seems that some fisherman came to his relatives and claimed there was an unpaid bill of a staggering 40,000 Taka—why the man would have bought so much fish remains an unsolved mystery of course, much to the consternation of his super organised and achiever family.

বেসিকটা এক

The Sameness of Rituals

At the base, it is all the same, he says. An old religion is replaced by a new one, old rituals leave their traces. Then it becomes important to forcefully prove that we are different.

Manasa and Lokkhi

Manasa, the Snake Goddess and Lokkhi or Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and fulfilment are deities of Sanatan Dharma (Hinduism), sure, but have not many of our people prayed to them a few centuries ago? he asks. Also, who does not fear the snake? Who does not wish for wealth and grace? So, the language of our everyday life retains the words; in our everyday gestures we carry residues of old beliefs, he says.

Salamotbhai cooking for us in his house.

Salamotbhai cooking for us in his house.

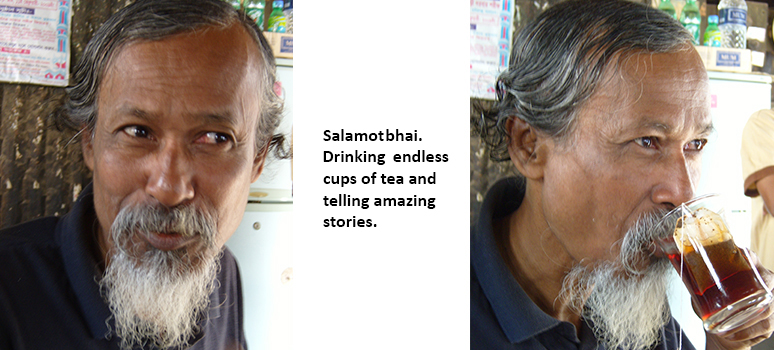

Salamotbhai also mediated between disputing groups, as it happens in village assemblies; I have seen him as being especially active in cases of abused and abandoned women. He was socially active in various organisations and worked also as a journalist and was an active member of Faridpur Press Club. But all of this might have been just dispensable activity—things he did to fill up his time. He also spent hours in adda, chatting with young and old alike, while chewing paan and smoking endless cigarettes (in the last years he had given up smoking). His addas took place in a few special haunts of Faridpur, such as Khondakar Restaurant or Shambhunather Cha-er Dokan, the famous teashop of Shambhu da, where we met him first time and through him two of our greatest singers of The Travelling Archive—Habib and Laila.

Salamot Khan was born into an urban, affluent family of professionals in East Pakistan (think they might have been from Mymensingh; Salamotbhai talked about having a plot of land there, where he planned to finally move and graze goats). This family would become one of the pioneering industrialist families of Bangladesh, the Beximco group. His older siblings, including the women, had all done extremely well in life—they were lawyers, scientists and academics and some of them taught in Western universities or held important posts or ran businesses.(He had an elder brother, his ‘Dada’, who was a retired senior official in the UK, and who called him every day from his home in Muswell Hill in north London and every time he called, Salamotbhai became the obedient little brother Nilu to him, ‘Ji Dada, hyan Dada, achchha Dada. . .’ was all we heard him say.) Salamotbhai, however, was a medical school dropout, known even in his youth for his eccentricity and localisms. He famously hated to leave Faridpur; the local was his universe. He would tell us stories about how he went to medical school in Rangpur in North Bengal and from there he would cross the border and go to the cinema in Cooch Behar in West Bengal and how he had a motorcycle which he would ride and how he loved Nescafe and so on his way back from Cooch Behar, he would buy jars of instant coffee. He also vividly described that accident he had which was a turning point of his life, when he gave up studies once and for all. He was coming back from Cooch Behar and his bike skidded and he fell and was gravely injured, for which he had to stay in hospital for months. More important for him though was the fact that all his coffee jars broke when he fell. He would tell us how he remembered that accident as a strong smell of Nescafe—that was the only sensation which his mind had retained.

Salamot Khan was born into an urban, affluent family of professionals in East Pakistan (think they might have been from Mymensingh; Salamotbhai talked about having a plot of land there, where he planned to finally move and graze goats). This family would become one of the pioneering industrialist families of Bangladesh, the Beximco group. His older siblings, including the women, had all done extremely well in life—they were lawyers, scientists and academics and some of them taught in Western universities or held important posts or ran businesses.(He had an elder brother, his ‘Dada’, who was a retired senior official in the UK, and who called him every day from his home in Muswell Hill in north London and every time he called, Salamotbhai became the obedient little brother Nilu to him, ‘Ji Dada, hyan Dada, achchha Dada. . .’ was all we heard him say.) Salamotbhai, however, was a medical school dropout, known even in his youth for his eccentricity and localisms. He famously hated to leave Faridpur; the local was his universe. He would tell us stories about how he went to medical school in Rangpur in North Bengal and from there he would cross the border and go to the cinema in Cooch Behar in West Bengal and how he had a motorcycle which he would ride and how he loved Nescafe and so on his way back from Cooch Behar, he would buy jars of instant coffee. He also vividly described that accident he had which was a turning point of his life, when he gave up studies once and for all. He was coming back from Cooch Behar and his bike skidded and he fell and was gravely injured, for which he had to stay in hospital for months. More important for him though was the fact that all his coffee jars broke when he fell. He would tell us how he remembered that accident as a strong smell of Nescafe—that was the only sensation which his mind had retained.

Such was the quality of Salamot Khan’s tales. Was there actually any broken coffee jar ever in his life? We do not know, but there was something essentially sensuous about the way he narrated his experiences. When we were first introduced to him, we were also introduced to the story of his pet, wild eagle, the injured bird he had adopted. Was there really such a bird? Or was this another of his fables? We knew that Salamotbhai does not usually invite people to his home, so there was no knowing if there was a bird by the name of Ishu who fed out of his hands. In the ten years that we knew him, I did manage to have him invite us once though, and that was the most wonderful experience we had and he had cooked for us the greatest meal ever. That was also when we met Ishu, the sad and solitary eagle.

Did he know that we only half-believed his stories which we loved to hear again and again? They had an unreal quality about them. Like ghost stories told in the rain.

Did he know that we only half-believed his stories which we loved to hear again and again? They had an unreal quality about them. Like ghost stories told in the rain.

ইলিশ ও ভূত

Salamotbhai tells stories about ghosts who live on trees and love to eat fish.

Talking about rain, we once went to the Padma with him—we have been to the river with him on several occasions and once we also recorded Ajmal Fakir on a boat—but this time that I am talking about, we were walking along the shore and saw enormous black clouds forming in the sky. They looked like they were coming to gobble up the earth. Salamotbhai said we should go to the tea shop on the river bank. That is what we did and as soon as we had reached the shop, it began to rain. Rain is too gentle a word to describe the rage which was unleashed by the heavens above. It was frightening and beautiful, all at the same time. Sukanta recorded the sound of that rain while a red fire burned in the stove in one corner and we had cups and cups of tea and crisply fried daalpuri with beet laban or black salt.

On the day I heard of Salamotbhai’s passing. I remembered the power of that evening when the sky and river had become one and the same universe before our eyes. I thought of The Little Prince and that last landscape which the narrator had described as the loveliest and saddest he had ever seen, for it was there that the Little Prince had appeared and from there that he had disappeared. So it has been for me. This whole year since Salamotbhai has been gone, I have remembered that day when the sky came down on our earth to cover us up. I did not know then, but when I looked around later, after the sky had receded, I saw that it had taken Salamotbhai away with it, into its world, never to give him back to us again. If only we had known, we would have held him tight and never let him go. ছাড়িয়া দিতাম না, বন্ধুরে . . .

We do not like to go to Faridpur anymore. The place is over for us. As it is, songs and singers are in a crisis in our world. Ibrahim Boyati, one of the finest artists we have recorded there, hesitates to sing now. But that is not the only reason why we have been absenting ourselves from Faridpur. If we don’t go, then it becomes possible to believe that Salamotbhai is there, just a phone-call away, across a border he found meaningless to cross, so he didn’t.

বর্ডার না-পেরোনোর গল্প

He will never get a passport or else his Dada will take him to England and not let him come back.

Salamot Khan was an inimitable storyteller. He spoke in words and images, he had a camera which he loved to play with and he had words which he could craft into tales. Recordings are not the real thing, they are only an image of what transpires in the real moment. Yet, here is a glimpse of a man for whom the world was not only made of humans, but there were birds and flowers and fishes, and rivers and horses and ghosts and reptiles too to live with. . .

The Snake Stories

সাপ ১

সাপ ২

সাপ ৩

He was also a great pickle-maker, stirring fruit and spices into the jar, mixing them with oil and sunlight. The last couple of times we went to Faridpur, he would fill our bags with goodies such as khejur gur (date molasses), pitha, and pickle. The last time we met, in 2014, the boot of the car was filled with food. And we had come only a few kilometres towards the border when my phone rang, and it was Salamotbhai—Didi (that is how he called me)! Achar dilam na to! I forgot to give you the pickle!

So I assured him that we would go back soon.

Through his eyes…

Post Script

Louis Sachar’s novel for young adults, Holes, describes pickled onion and peaches found buried in the belly of a sunken boat. Such pickles give life to the hungry and thirsty in Sachar’s book: the two boys who are fleeing captivity to find freedom. I want to believe that in Salamotbhai’s house, there are rows and rows of pickle stashed away, out of which a bottle or two he had kept for me. Should I go and find them now, or many years after, when his house is buried in the sand of the riverbed which was once his land, I can quench my thirst by drinking its juice. or savour away at the spicy, juicy tamarind, making sounds of satisfaction with my tongue.

A recording is something like a pickle—mixed with spices and sunlight, different from the original, yet it also retains flavours of the old. It can bring the dead to life. In these recordings which Sukanta made in Shambhunath’s teashop or in Milonbhai’s house, the rain plays with Salamotbhai’s voice to tell stories of its own. Shambhuda, gone; Sadek Ali, gone; Ishu, ‘flown’; Laila, untraceable; Nuru Pagla lost; Ibrahim Boyati, silenced, Gosai Das migrated perhaps. . . At least the recording can sing its own song of a time when the song used to flow like a river.

Written by Moushumi, 25 June 2016

Essay in text, image and sound created by Sukanta. Salamotbhai’s photographs are also his. Photos of Ishu and Salamotbhai cooking taken by Tajdar Junaid.