Film, Art or Illustration?

We have also brought to this page our own attempts to more creatively engage with our field recordings, connecting with the works of others before and after us. In Film, Art or Illustration?, we are searching for a lineage, a place to belong. Is what we are doing also not part of something larger; are we not one voice among many?

Other than recording, documenting and archiving our recordings, other than creating this website, and other than creating our soundtracks and booklets for our record label, we have also begun to explore ways of connecting our own recordings with the recordings of others through the audiovisual medium. What we record is only a moment, the moment a sound is uttered, the moment a boat passes us by, the moment of trance during a performance. Such moments are all essentially ephemeral. And yet there were others before us and those at the same time as us and others who will come after us—all of us recording such passing moments of history. What is recorded gives the passing moment a longer life, if not eternity. At the same time, in its recorded life, the moment seems to be robbed of life, held in permanent stasis, unable to die.

Such ideas lie behind the works we are sharing with you here. We have been working with archival material—sound, image as well as text, setting up dialogues between the recordings and collections of others with our own. It is an attempt to weave together layers of time, an attempt to listen to history, an attempt to see our work in a certain continuity.

Art or film or mere audio-video illustration of image and sound—we leave it for viewer and listener to decide.

_____________

Life of Rivers

In 2011 we were commissioned a film by the National Maritime Museum in London, using footage from their film archives, as part of a series of programmes titled ‘Traders Unpacked’ which they had organised to mark the opening of a new gallery in the museum, on Britain’s trade with Asia. They sent us two films—assemblage of footage really–both from the 1950s, on rivers and boats of what is now Bangladesh, East Pakistan then. One film was shot by the Basil Greenhill (1901-2003), who was a scholar of rivers and seas and sailing vessels and served as a most proficient director of the NMM from 1967 to 1983. He worked as a diplomat in East Pakistan in the 1950s and out of that stay came the book, Boats and Boatmen of Pakistan, and this footage of boats, boatmen, fishermen, rivers and shores. The other string of footage came from someone by the name of Corlett (whose identity we could not trace; even the museum could not give us any detail). The character of this footage was quite different from Greenhill’s—larger vessels, ships, harbours, the river going towards the sea, more industrialised rivers and so on. Corlett’s film was silent, but the images seemed to suggest all this, Greenhill’s had a voiceover, which was so soft that that film too sounded silent.

After we got the footage, we began our research in Kolkata first. Later we went on a trip on the rivers of Bangladesh in October. Finally Sukanta, the films person, edited and wove the footage into a narrative which we decided to call ‘Life of Rivers’. He also created a soundtrack for our film using mostly our own field recordings and his personal recordings of ambient sounds and some bits of an older recording of the famous singer of folk songs, Ranen Roychowdhury. In 2010, Sukanta had digitally remastered Ranen Royshowdhury’s home recordings on audio cassettes, most probably from the seventies, for a CD released by Lokosarswati.

We went to the rivers of Bangladesh in search of sounds for our film. We went to the Padma, Meghna, Sitalaksha. Our friends told us stories about rivers and boats and boat race and different kinds of songs associated with rivers—shari, jari, bhatiyali, bichchhed, Manasar gaan. They also told us about fishes, fishing and ghosts who love to eat fish. In Boats and Boatmen of Pakistan (published 1967), Greenhill wrote: ’During the south-west monsoon and for months after it is finished, East Pakistan becomes a world of water. It is this fact which has given peculiar characteristics to the human life that is lived there. . . it is a quiet world of still evenings on lonely islands in great rivers when the only sound is the sighing of a dying breeze among the swamp grasses. . . this world has songs and poetry of its own.’ Between the rivers Greenhill saw and our own, there are huge gaps. We rode a ship through the night, but did not hear any sighing breeze. No fabled boatman was singing his timeless and shoreless bhatiyali. Instead, a fishing boat went by and someone was playing music on his mobile phone. The rivers are not silent anymore, Sukanta said.

In an essay in the Baul Fakir Utsav journal, Arshinagar, in 2012, Moushumi has written about their journey for songs and stories of rivers.

_____________________

Footsteps of Sound

This is an audio-video installation artwork we created as The Travelling Archive, for an exhibition on early sound recording in India, ‘La Presencia del Sonido’ (The Presence of Sound) held at Foundacion Botin, Santander, Spain in August-September 2013. The exhibition was curated by Nida Ghouse and Nuria Querol.

The Travelling Archive wrote a long essay for the catalogue as well as an introduction to their artwork.

Here is the introduction to Footsteps of Sound.

A sound rises from the mirdanga drum.

I hear its footsteps,

It stirs my heart,

I feel in me that rumble and roll.

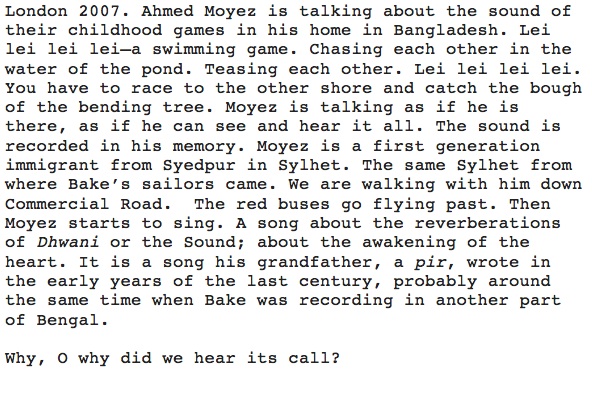

Why, O why did I hear its call?

–Mojiruddin, early twentieth century mystic poet and pir of Syedpur, Sylhet.

What did Arnold Bake hear in that January of 1932 when he was recording and filming in Kenduli, the ancient annual fair dedicated to the 13th century poet Jaydev, on the bank of the river Ajoy, in Birbhum, Bengal? Standing in the middle of the chaos of Kenduli today, squashed from all sides by crowds, with noises rising from every corner of this space, where to look for the sound and the silence that Bake could have heard? Listen to his cylinders from that recording session? What we hear is not what he heard. It cannot be.

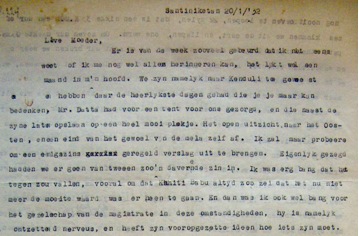

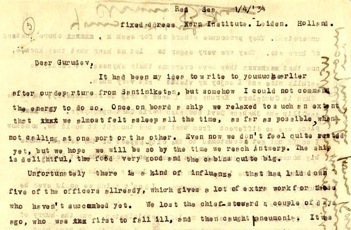

Letter Home. Bake to his mother from Santiniketan. 20 January 1932. Source: Kern Institute holdings at the Special Collection section of Leiden University Library.

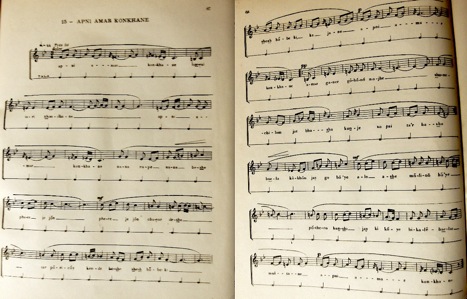

They were recording in Kenduli between 14 and 16 January 1932. Kenduli Mela, where the bauls come with their songs. ‘Song to them is a necessity, for it expresses the yearning of their soul,’ Bake wrote in his book with Phillip Sterne, Twenty-Six Songs of Rabindranath Tagore . On 31 January 1930 he had recorded an album with Pathe under the supervision of Hubert Pernot. ‘Chansons de Rabindranath Tagore’. One of the songs in it is Apni Amar Konkhane.

From Twenty-Six Songs of Rabindranath Tagore. Paris: Librarie Orientaliste Paul Guenther, 1935, pp. 67-68.

Bake’s note in this book about the song goes like this: A song entirely in the style of Baul songs of Bengal. The theme as well. . . it has direct appeal and not the metaphysical associations which a theme like that would have for a Western mind. The accent, often falling on the last note of a melodic figure, gives the song that urging and questioning character, wonderfully expressive of the essence of the bauls.

Do we hear in Bake’s recording something of what he had heard in this song? And, retracing these footsteps of sound, can we hear in it something of what Tagore might have heard in the songs of the bauls?

Image: Rabindra Rachanabali (Complete Works of Tagore), Vol. 9. Calcutta: West Bengal Government, 1961, p.3.

Tagore’s novel Gora (1910) begins with a scene where a baul is singing in a street of Calcutta. Binoy, a nineteenth century young Bengali intellectual, hears him from his balcony. It is a song about the mystery of the comings and goings of the ‘unknown bird’ into the cage of life. He wants to call the baul and write down the words of the song, but he is also feeling sluggish.

‘The first Baül song, which I chanced to hear with any attention, profoundly stirred my mind. Its words are so simple that it makes me hesitate to render them in a foreign tongue, and set them forward for critical observation. Besides, the best part of a song is missed when the tune is absent; for thereby its movement and its colour are lost, and it becomes like a butterfly whose wings have been plucked. The first line may be translated thus: “Where shall I meet him, the Man of my Heart?”’ From lecture ‘An Indian Folk Religion’, by Rabindranath Tagore, compiled in Creative Unity. London: Macmillan and Co. Limited. 1922.

After their second India trip, the Arnold and Cornelia Bake were returning home.

Sailing on the Red Sea. Bake’s letter to Tagore. 1 April 1934. Source: Rabindra Bhavan, Visva Bharati, Santiniketan.

‘All the sailors and stokers come from East Bengal and as the captain allows me to go wherever I like, I have heard quite a number of songs from their districts, mostly Sylhet and Noakhali. Some songs are really very attractive. Their dialect is not easy to understand. They pronounce a hard ch for each k, choro instead of koro. . .’

Watch trailer of Footsteps of Sound.

_____________________

- Baul Fakir Utsav Journals

- Response

- Essay

- Costis Drygianakis and Yiorgis Sakellariou, who have worked on Russian and Lithuanian folk music respectively, share their thoughts on the notion of traditional music

- Renee Lulam writes about oral traditions in the Khasi Hills

- Robert Millis writes about his listening memory of American folk music