Barisal and Sylhet, Bangladesh. 08 to 18 August 2012. Manasamangal by various artists

The four recordings in this session come from an ongoing project on Manasamangal or the Song Cycle of the Snake Goddess, Manasa, which we have been recording, bit by bit, in different places in Bengal for some years. The idea is that over a period of time we will have different versions of the story of Manasa sung in different forms and styles across a whole range of places within Bengal and beyond, showing it as a living and evolving tradition.

The Manasamangal, also known as the Padma Puran, is a Mangalkavya sung for Manasa (the Mangalkavyas are devotional paeans to some local deity, composed in Bengal between the 13th and 18th centuries). This ritualistic song cycle is performed as a timeless but also living tradition in Bangladesh and eastern and north-eastern India; even in southern India. It is performed usually in the monsoon month of Sraban, i.e. from mid-July to mid-August, when it is the time of the snakes in a land of flooding rivers and swamps.

Book cover: Baish Kobir Padmapuran

In August 2012, we travelled for 10 days in Barisal and Sylhet, and caught parts of the story of Chand Sadagar, the merchant who refused to worship Manasa, preferring Siva instead; of Manasa’s anger and revenge against of Chand; of the death from snakebite of Lokkhindor, Chand and Sanaka’s last remaining son, on his wedding night, (all other sons were drowned in sea and Chand’s merchant vessels destroyed, before the birth of Lokkhindor); and of Behula (Bipula in Sylhet), Lokkhindor’s newly-wedded and widowed bride, sailing to the heavens with her husband’s corpse with the pledge to return him to life.

There are many tales about the origin of Manasa, a deity of partial godhead (for she may have been born when the aroused Siva’s semen dropped on a lotus or padma flower; hence she is called Padmavati), or she might have been a creation of the sage Kashyap’s mind or manas, hence Manasa. There is also the incident of Manasa losing an eye to the fury of her stepmother Chandi. Whatever her origin, Manasa is a one-eyed goddess who presides over a world of snakes and reptiles, and humans who live in close contact with such creatures. In practical terms, she is worshipped by those who need her protection; that is, those who risk snakebite or stormy rivers and seas in their everyday lives. Manasa is worshipped for her ability to prevent and cure humans of snakebite; she also brings them prosperity and fertility. When praised, she is benevolent and kind; when undermined and humiliated, she is full of vengeance.

Pages from Baish Kobir Padmapuran

In both Barisal and Sylhet, the Manasa Mangal is sung from start to finish through the whole month of Sraban, mostly by women, as a community ritual. So also in Murshidabad, where Sukanta had made some recordings of Manasar gaan song back in 2009, when we did not have such a project in mind but he was only recording sounds for a feature film. Anyway, the fact is that in each place they sing their own versions of the same story, reading from panchalis or texts written down hundreds of years ago by their own regional poets. These poets localise the Manasa story—the land is described in local terms, rivers bear local names, the food is what local people eat—shaak, machchh and so on. . . Such are the signs of any great story, when it can be both local and universal.

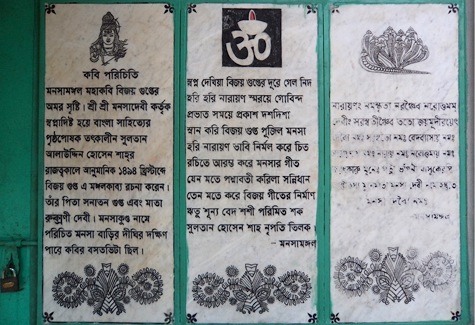

The text most commonly followed in Barisal is by Bijoy Gupta, a 15th century poet of Goila, Agailjhara in this southern district of Bangladesh. The text followed in Sylhet, on the other hand, is the Baish Kobir Padma Puran, credited to 22 different poets, prominent among whom is the 15th century Narayandeb. As historical accounts go, Narayandeb’s original home might have been in Rarh in the heart of West Bengal, but it is believed that his family later moved to Kishoreganj, in the east of central Bangladesh. Interestingly, Narayandeb’s narrative is as popular in eastern Bangladesh as it is in Assam, and by Assam we are not only talking about places contiguous with Bengal, such as Cachar, which are in effect extensions of the Sylhet region. We are here talking about places distant and distinct from Bengal such as the Darrang region of central Assam. Here there is a very old tradition of singing and dancing the Suknani Ojapali (or Oja Pali), in praise of goddess Manasa; Suknani being an acronym of Sukabi Narayandeb.

So then, as we move on our trail of Manasa’s songs, listening and watching, recording and writing–for much of the Manasa rituals are also very strongly visual—we get caught in a complex web of overlaps, intertwines and juxtapositions. Enchanting new maps of rivers and forests, poets and devotees, snakes and charms, life and death, open up before us. There is something primeval, yet universal about this world. Behula sails with the dead from shore to shore, but we are assured by fore-knowledge that the dead will eventually come back to life and Manasa’s mangal or blessings will prevail.

What we have recorded so far lays out a basic structure of an ambitious field recording project that will take several monsoons to complete. The Manasa Mangal is a song cycle with important historical, anthropological, ecological and political implications of contemporary relevance. It upholds the image of a cosmos where the human and divine and animals and plants are bound in a relationship of harmony. The stories around the origins of Manasa and her place in the Hindu pantheon—tribal or Hindu, of partial or full godhead—lead to further questions about our social and racial relationships. Who is Manasa? What does she symbolise? More than a hundred years ago Ananda Coomaraswamy and Sister Nivedita had written: “[The] legend of [Chand Sadagar and] Manasā Devī . . ., reflects the conflict between the religion of Shiva and that of female local deities in Bengal. Afterwards Manasā or Padmā was recognized as a form of Shakti . . . and her worship accepted by Shaivas. She is a phase of the mother-divinity who for so many worshippers is nearer and dearer than the far-off and impersonal Shiva. . .” The related question concerns Behula; who or what is she? Is she creating, or following her destiny? Is she a free will, an indomitable spirit expressing her own desire for life and love or herself an object of desire, dancing to please the gods?

Perhaps it is too early in our research to try to find answers to these questions. We can try to talk about something else, which is no less important, if not more. On our first Manasa Mangal field recording trip in Barisal in August 2012–our third trip to the town–we were faced with a complex identity question. Our young friend and guide in this small town is Supriyo Datta, who works for an NGO, Nagarik Udyog. He is a Hindu by birth and is conscious of his community identity. He is taking part in the restoration of the local temple; it is an important social and political gesture, as assertion of a presence. We walk through Barisal and he talks of thriving real estate businesses, the filling up of the canals which once gave Barisal its uniqueness; he talks of past glory. It is very common to talk about such things, as there has been so much change in the last 60 years. Surpiyo very consciously belongs to his community but he is also consciously not communal. They talk about practical things. His young friend Suvro has just got a job in a government bank—they say it is a big thing for someone from the minority community to get employment in a government organisation. Standing by the lake in downtown Barisal where students and others gather every evening, Supriyo says, India makes it harder for us. The fence, the killings—the more such things happen, the more difficult it gets for us. They see us as enemies, at an everyday level.

This ‘us’, this ‘them’—this starts to trouble me. Supriyo, Suvro—they are saying such things to us because for them we come from the other side of the border, from the ‘safer’ land where ‘we’ are the majority by virtue of our birth.

Stones with short biography of Bijoy Gupta and the story of poet’s dream about Manasa, Goila, Barisal

Then when we go to Goila, Agailjhara, where the poet Bijoy Gupta’s humble house and temple used to be, the place is slowly being promoted as a pilgrimage as Manasa puja is a very big thing for this whole region and Bijoy Gupta is part of the heritage of the region. The old temple which was crumbling down has been built into a glass and steel structure. What an aesthetic shift! Then there will be guided tours, bus service, shops, hotels, better roads, lights—will work to give the minority community some agency while some people, irrespective of community identity, will make some good money.

Bijoy Gupta’s Manasa Temple. Left: Before. Right: Now (2012)

For now the shaded places around the temple are still very beautiful. There is a performance area, where an annual festival of royani gaan—a theatre based on Manasa’s story—is held in these monsoon months. Then on Sraban Sankranti—the last day of Sraban which is usually around 15 August, thousands upon thousands of devotees come to the temple with their offerings of milk and banana. Manasa is said to have been an Adivasi (tribal) goddess who later got appropriated into the Hindu pantheon; in the past she was only worshipped by the lower castes. Hence her puja is also very humble, materially she does not ask for much. It is mostly the women who come to seek her blessing on behalf of the whole family. Among them are also many Muslim women, some even in burqa, who have come with their offerings. They will not be allowed to enter the temple, so someone else will place their offering before the icon of Manasa—again untouchability and desecration—but it seems as though people naturally accept this system of simultaneous exclusion and co-habitation. So long as them and their families are blessed, so long as ‘mangal’ reigns.

Royani performance in a manasa temple at Kaokhani, Barisal

Agailjhara women-Mangal Gaan

Bakal village in Agaijhara sub-division of Barisal district. 8 August 2012

This recording took place in the house of Bidyut Kumar Das, who works with Supriyo Dutta for Nagarik Udyog. A fairly educated community, reasonably well-off, many of the women in the congregation also had jobs. Bidyut’s wife, in fact, is a school teacher. However, the ritual of singing Bijoy Gupta’s Manasa Mangal panchali continues and even very young girls take part in it. On this day, as we were going to visit them, they made the occasion very special by singing through the day till late at night the story of the death and re-birth of Lokkhindor. It is the day of Lokkhindor’s maran and jiyon. Which means that the worst is over and now life will be renewed. They ended the day’s session with this song seeking Manasa’s blessings. This song is not part of the Bijoy Gupta text, but it is part of the ritual. ও কি জিলো,/জিলো লখিন্দর সর্বাঙ্গ সুন্দর/খণ্ডিল পদ্মার বাধ।

Wake up Lokkhindor, Padma’s curse has broken.

Women singing Manasamangal in Agailjhara, Barisal

The song then goes to name individual family members—those who must be blessed. Interestingly, they only sing the names of the men. বিদ্যুতের কল্যাণে এই দংশন জিয়াইলাম রে, খণ্ডিল পদ্মার বাধ। আশিসের কল্যাণে, বিভুতির কল্যাণে. . . One after another, they remember the boys and men of the community. Do the girls not matter then? They certainly do. Once the women sing: সবার কল্যাণে এই দংশন জিয়াইলাম রে. . . seeking protection for ‘All’. The women must be part of that ‘All’. But there is also an order in this universe, a clear separation of the world between those who seek protection for others and those who get protected. What can one say? The world of Manasa Mangal is a world riddled with irony and contradiction. There were many women singing that day. I have many names written in my notebook. Some came, some left, as the singing went on for the whole day, till late in the evening. Bidyut’s mother Rekharani Das sat like the matriarch on a chair, chewing paan; she has bad knees. The rest sat on the floor, around the book. One read, the rest sang in a chorus. They women took turns to lead. They did not really need the book, as they knew the whole text by heart. But they would also not be able to sing without the book, as it was integral to the ritual, sitting around it, like it was the deity. Purnalakshmi Sarkar looked like she could be 90—they said that she belonged to the Victorian times, উনি তো মহারানীর রাষ্ট্রের মানুষ। Jhumur Mondal studied in Class X, Nupur in Class VI, there were girls who looked like they should be going to school, but were already married, with think vermillion in their parting, even with children some of them.

What struck us in Barisal I think was the energy and dynamics of this social gathering, more than the pleasure of listening. The music was not always coming together, there were too many outside influences—of the radio, television, of ‘royani’ theatrical performances. As a result, what the tune of the land was, became hard to tell. It is only in songs like this mangal gaan that we got drawn into the plain and repetitive cycle of the panchali form. Such moments were rare in Bidyut’s village home in Bakal, Agailjhara. There was a certain festivity in the air, but less intensity in the sound.

Bahara girls-dukkher majhe janmo

17 August 2012

Almost 300 km to the northeast of Barisal, Bahara is one of those little villages of the Sunamganj ‘haor’ region which remains water-locked for more than six months every year. It is like those little planets Exupery writes about in The Little Prince—from one end to another, you can measure by the number of footsteps you take. Somehow there was no distraction in the Bahara singing. They noticed us, gave us seats and carried on singing. We made three sets of very interesting and different recordings that day. One was in the house of Rabindra Master, a retired school teacher, idealistic and pedagogic, who recited morally uplifting poetry with great emotion and action. Another was a group of men and women singing the Padma Puran, more in the style of kirtan, with accompaniment.

Rabindra master reciting poems

But what we have here is a group of three teenage girls, high school students, singing in the courtyard of their house, in front of their Manasa temple. The girl who is leading is Rimpi Rani, and she is totally unostentatious and absorbed in her singing, and her friends follow her with likewise dedication. The part of the story that they are singing is about the old Brahmin woman (Manasa in disguise) cursing Bipula (same as Behula, Lokkhindor’s bride) when she has gone to the pond to take a dip, that she will become a widow on her wedding night. ‘ছদ্মবেশে চন্দ্রধর ও লক্ষ্মীন্দরের গমন, বিপুলার প্রতি ব্রাহ্মণীর শাপ এবং বাদানুবাদে ব্রাহ্মণীকে পরাজয়’। The refrain that they sing is not part of the main text and it is something for which they have a stock. Here they are singing a lament, হায় গো, দুখের মাঝে জন্ম আমার গো। /হায় গো পাইনা শোকের সাড়া . . . Why lament? Because in these stories which are told and re-told again and again, the eventualities are known from before, and so the grief is also anticipated. This is the last-but-one day of Sraban and the next day is the day of immersion.

Rimpi Rani singing Manasamangal, Bahara

Nocturne

Shukhline, Dumra, Ghungiar Gaon. 17 August 2012

The night before the immersion of Manasa in the waters of the haor in this Shalla part of Sunamganj, is a night of music. The book, Baish Kobir Padma Puran, is read across the villages—Shukhline, Dumra, Ghungiar Gaon, all of which touch each other.

Haor

Turn around a corner, the name of the place has changed to become another village. We were sitting on the roof of our friend and guide in this Sylhet region, Suman Kumar Das’ house after dinner. His parents live in Shukhline, he works as a journalist from Sylhet town. It is he who had arranged for us to go and do this recording. On the terrace, there was music coming from every direction. Then Sukanta began to walk back towards our guest house. Walking stopping, walking. Approaching the music, then going past it. That night the sky was heavy with clouds. শ্রাবণের প্রায়-শেষ রাত।

Manasa idol

Dumra men-bharosa gobindo

18 August 2012

This was the last day of the month of Sraban, শ্রাবণের শেষ দিবস। That day it is the men who sing in these temporary islands of Sunamganj in Sylhet. Something from the Padma Puran, not in any specific order though. The men go from house to house singing and in every house they are offered slices of the coconut fruit. Here in this recording, Shubhas Bose and his companions are singing the story of Chand Sadagar on one of his mercantile voyages, meeting the king of some land, with coconut and other offerings. The Chorus sings Bhorosa Gobindo more/ Rakho ranga paaye, —interestingly the gods come together in these utterances and the distinctions of Shaiva and Vaishnava seem to dissolve when it comes to the everyday lives of ordinary people. Unlike Chand of their Manasa Mangal story, they are flexible and open to the idea of any god who may give them support and protection.

Men singing Manasamangal, Dumra

The song has now risen to a height, there is percussion accompanying the singing, the men dance as they sing. Today is the day of closure of a whole month of festivity. The boats will sail on the waters of the haor, the men and boys of every house will carry their Manasas with them, rarely a girl, and they will all be singing along the way. Then when they reach the deep point in the haor, they will take the plunge with their goddesses. Leaving their Padma and Neta to meld with the waters, they will rise and swim back to the boat.

Taking their Manasas to the deep point in the haor

At home that night, the house is empty of the goddess, but the story must be sung to its finish. Now the women and men will sing the rest of the Padma Puran. They had left it at the death of Lokkhindor. Tonight Bipula will sail to the heavens and bring back her husband to life and with him his brothers and their vessels will all be restored. Prosperity will prevail for one more year. Not prosperity perhaps, but the hope of it at least.

Immersion procession in the haor

Written in 2014.

Related links

Manasa in patachitra

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gQkoiZUyuT8

A song by Dukhushyam Chitrakar and his team, scroll painters from Midnapur. This song was recorded in an exhibition titled “Ekchala” by various artists at Birla Academy, Kolkata in Dec 2010. The song was performed by the patuas as part of an installation on rivers by the artist, Amitava Adhikari.

- Saptiguri, North Bengal. 27 November 2003. Nirmala Roy

- Bolpur, Birbhum. 25 November 2003. Nimai Chand Baul

- Kolkata. 4 September 2019. Purnadas on Nabani Das Baul

- Surma News Office, Quaker Street, East London. 27 February 2007. Ahmed Moyez

- Ambikapur, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 29 April 2006. Hajera Bibi

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 22 April 2006. Chandrabati Roy Barman and Sushoma Das

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 21 April 2006. Arkum Shah Mazar

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 20-21 April 2006. Ruhi Thakur and others

- Jahajpur, Purulia. 27 February 2006. Naren Hansda and others

- Faridpur, Bangladesh. 24 January 2006. Binoy Nath

- Uttar Shobharampur, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 22 January 2006. Ibrahim Boyati

- Baotipara, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 21 January 2006. Kusumbala Mondal and others

- Kumar Nodi, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 21 January 2006. Idris Majhi and Sadek Ali

- Debicharan, Rangpur, Bangladesh 18 January 2006 Anurupa Roy & Mini Roy, Shopon Das

- Mahiganj, Rangpur, Bangladesh. 17 January 2006. Biswanath Mahanta & Digen Roy

- Chitarpur, Kotshila, Purulia. 28 November 2005. Musurabala

- Krishnai, Goalpara, Assam. 30 August 2005. Rahima Kolita

- Chandrapur,Cachar. 28 August 2005. Janmashtami

- Silchar, 25 August 2005, Barindra Das

- Kenduli,Birbhum. 14 January 2005. Fulmala Dasi

- Kenduli, Birbhum. 13 January 2005. Ashalata Mandal

- Shaspur, Birbhum. 8 January 2005. Golam Shah and sons Salam and Jamir

- Bhaddi, Purulia. 6 January 2005. Amulya Kumar, Hari Kumar

- Srimangal, Sylhet. 27 December 2004. Tea garden singers

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 26 December 2004. Abdul Hamid

- Dhaka, Bangladesh. 24 December 2004. Ali Akbar

- Dhaka, Bangladesh. 23 December 2004. Monjila

- Changrabandha, Coochbehar. 16 December 2004. Abhay Roy

- Santiniketan, Birbhum 27 Nov 2004 Debdas Baul, Nandarani

- Tarapith, Birbhum. 14 October 2004. Kanai Das Baul