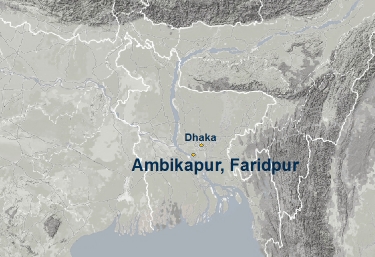

Ambikapur, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 29 April 2006. Hajera Bibi

About eight months after we met Hajera Bibi in the courtyard of her house in Ambikapur, Faridpur, the 93-year-old singer and composer passed away, in December 2006. So this is probably the last recording of her voice, or maybe there were other visitors, although when we saw her, she seemed to be living a forgotten life, in silence. Hajera Bibi was one of the first women of East Pakistan, later Bangladesh who gained recognition as a singer and composer in the mystic tradition of bichar, bichchhed and murshidi gaan.

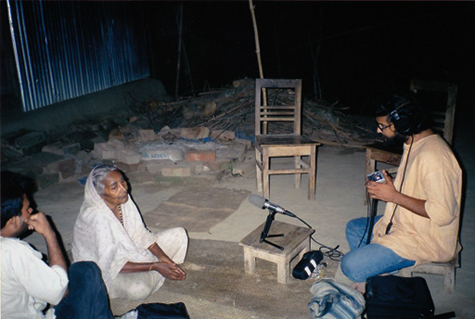

Throughout this recording session Hajera Bibi hovered between forgetting and remembering. We asked her questions, (besides Sukanta and me, there were Sanjay, Pradip and Salamot bhai with us, all of them local), and Hajera Bibi answered as well as she could remember. Sometimes her grand-niece, Jonaki, intervened and said, Dadi is getting it all mixed up. However to us it seemed quite logical and lucid. There was a sense of loss and regret in what she said, expressed in the sounds and fading light of that evening, for she reminisced about her glorious days of evolving as an artist under the guidance of ‘Kobishaab’ or the poet Jasimuddin; about night-long sessions of bichar gaan or song debate with thousands of people listening to her and her favoured opponent, Halim Boyati; about the great composer of Norail, Bijoy Sarkar, being in the audience once; about her days of touring and recording for the radio. What happened then to all the songs she wrote and sang, even recorded? It was hard to imagine that this old woman, slightly bent with age but still able to potter around, sitting in the earthen courtyard of her little house, with few close, poor relations keeping her company—it is hard to imagine that this woman had such a full life once. Age, yes. But what about her glory and fame? And all the money she earned? There is no clear answer for such difficult questions? Or maybe there is the obvious one—who cares? Why is there no recording of her songs? Why no publication? Hajera Bibi told us that some years ago, someone from an NGO had come and taken away her sole surviving songbook; they said they wanted to publish her work; but there was no publication till the time when we met her. She had lost most of her things earlier, in the War of 1971, when her house was ransacked by the Pakistani soldiers; even certificates and gifts she had got for performing in President Ayub Khan’s time. Then she was taken once to UBINIG, an NGO with its head office in Dhaka, which is run by the radical thinker, writer and social activist, Farhad Mazhar. That trip she remembered with fondness. They took great care of her, she said; recorded her, learned songs from her. There were many white people. That was probably the last gesture of love, care and respect she got from the outside world. The rest was her familiar world of family and her shishyas (disciples), mostly powerless people like her. Hajera Bibi quietly died in the house of one her disciples, where she had gone to visit and bless them.

Sukanta recording Hazera Bibi

So much for a whole life spent in music. For being a unique woman who composed and sang songs in erstwhile East Pakistan, later Bangladesh, during a time of great personal and political struggle. Hajera Bibi was born Nonibala, into a Hindu family, married off early and widowed early too. Meanwhile her baby boy had also died. By the time she was 20 or so, her eventful life had come to a halt. How to live on after this? It was as if she could/would have to close the pages of her past life now and start afresh. She found within herself the power of music, also the potential to do music for a living. But this she could not do as the widowed Nonibala. She was mentored by Jasimuddin, converted to Islam, married again, went through wars and struggle, but also developed as an artist and lived in fame. Later she began to write songs in the philosophical and devotional mode.

We went to her, but it was rather too late. That evening she sang, je hale rekhechho murshid, shei hale thaki (O Master, I stay as you will for me). The song came out of her toothless mouth and her frail body, not as a complaint, but as submission. Now if we try to find her lost songs, my fear is that we will not be able to go too far back. Habib sang one of Hajera Ma’s songs in Shambhunath’s tea shop, Laila sang another, also Ibrahim Boyati. They are all from Faridpur. So, Hajera’s songs are still part of the region’s living tradition, at least in some small way. But where to go for more? In 2010 I met Farida Akhter, executive director of UBINIG, who told me that they had Hajera Bibi’s recordings from the time she visited them. They see her as one of their spiritual teachers. Perhaps they will upload those songs on their own website. If they do, we can link our site with theirs. Perhaps someone will have the perseverance to search for old cassettes of ‘Don company who had their offices in Motijheel’, and find some old cassettes of Hajera Bibi. Perhaps someone with a feminist bend will want to know more about her. Maybe someone will get something from the radio’s archives in Dhaka, although it is highly unlikely, considering the state of our archives in the subcontinent, especially government ones. For now, therefore, we are grateful for the songs and stories that Hajera Bibi gave to us, in her own voice, however ‘ultapalta’ (muddled and messy, as her grand-niece Jonaki complained) they might be.

It is easier to pay tribute to the dead than pay attention to the living. A Hajera Mela, or anniversary fair, is being held in Faridpur for the past few years.

Written in 2013.

- Saptiguri, North Bengal. 27 November 2003. Nirmala Roy

- Bolpur, Birbhum. 25 November 2003. Nimai Chand Baul

- Kolkata. 4 September 2019. Purnadas on Nabani Das Baul

- Surma News Office, Quaker Street, East London. 27 February 2007. Ahmed Moyez

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 22 April 2006. Chandrabati Roy Barman and Sushoma Das

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 21 April 2006. Arkum Shah Mazar

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 20-21 April 2006. Ruhi Thakur and others

- Jahajpur, Purulia. 27 February 2006. Naren Hansda and others

- Faridpur, Bangladesh. 24 January 2006. Binoy Nath

- Uttar Shobharampur, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 22 January 2006. Ibrahim Boyati

- Baotipara, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 21 January 2006. Kusumbala Mondal and others

- Kumar Nodi, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 21 January 2006. Idris Majhi and Sadek Ali

- Debicharan, Rangpur, Bangladesh 18 January 2006 Anurupa Roy & Mini Roy, Shopon Das

- Mahiganj, Rangpur, Bangladesh. 17 January 2006. Biswanath Mahanta & Digen Roy

- Chitarpur, Kotshila, Purulia. 28 November 2005. Musurabala

- Krishnai, Goalpara, Assam. 30 August 2005. Rahima Kolita

- Chandrapur,Cachar. 28 August 2005. Janmashtami

- Silchar, 25 August 2005, Barindra Das

- Kenduli,Birbhum. 14 January 2005. Fulmala Dasi

- Kenduli, Birbhum. 13 January 2005. Ashalata Mandal

- Shaspur, Birbhum. 8 January 2005. Golam Shah and sons Salam and Jamir

- Bhaddi, Purulia. 6 January 2005. Amulya Kumar, Hari Kumar

- Srimangal, Sylhet. 27 December 2004. Tea garden singers

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 26 December 2004. Abdul Hamid

- Dhaka, Bangladesh. 24 December 2004. Ali Akbar

- Dhaka, Bangladesh. 23 December 2004. Monjila

- Changrabandha, Coochbehar. 16 December 2004. Abhay Roy

- Santiniketan, Birbhum 27 Nov 2004 Debdas Baul, Nandarani

- Tarapith, Birbhum. 14 October 2004. Kanai Das Baul