Time upon Time: Arnold Bake in Bengal 2016

After ‘Time upon Time’

We had our exhibition ‘Time upon Time: Arnold Bake in Bengal’ at the Nandan gallery of Kala Bhavan (the school of visual arts) of Visva Bharati, Santiniketan from 7-15 March 2016. Based on our work of over a decade as field recordists in Bengal, and our archival research on field recordings from Bengal, this was our attempt at stopping for a bit to see where we might have come in our understanding of the work of Arnold Adriaan Bake and where we may go from here. Bake, a Dutch scholar, had more than 80 years before us worked in the same field as us, recording the same and similar musics, and often we hear his footsteps as we walk through our map of Bengal. ‘Time upon Time’ was our way to stop and listen. Also, a way of sharing our listening with others.

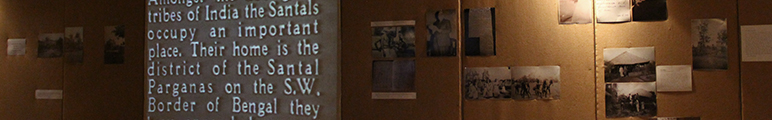

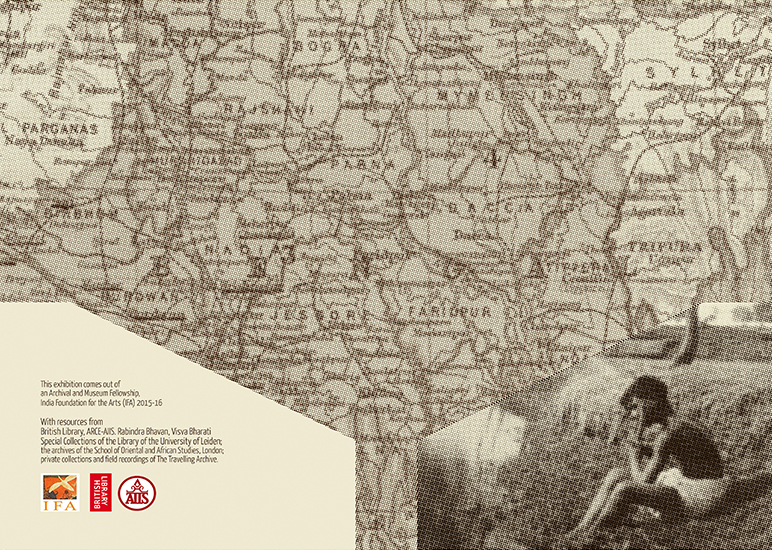

The exhibition was created with archival material; at the same time it tried to draw attention to the future of archiving by commenting on the very concept of the archive. With support of the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) through their Archival and Museum Fellowship, and a Scaliger Fellowship from Leiden University, we explored resources from several archives within India and abroad, including the British Library (see British Library’s blog post), Archives and Research Center for Ethnomusicology of the American Institute of Indian studies (ARCE-AIIS), SOAS and Rabindra Bhavan, Santiniketan. Thus, within the space of the exhibition, archives were getting connected, while we were discovering the overlaps between them and gaps too. This was for us a way to also examine how archives are constructed. In ‘The Archives’ section of our display, where the computer was presented as the repository of material from several archives, institutional and personal, an archive of archives so to speak, we presented recordings received as well as the recordings we have made, in provenance. So, at one level, ‘The Archives’ was a mere object, a computer holding files, presented by us as is, raw and unedited. Yet, it was in the presentation of this unedited and uninterpreted material that our subjectivity also got recorded; in the way that we had arranged these archives, or the way we presented their catalogues. Should we present them as they are presented by the archives, say with a gap in information which we know as a gap, or should we intervene in the matter? This was one of the questions we were grappling with. Furthermore, what could we do with related material which we considered to be vitally precious and important to this exhibition, but which we had found freely on the internet? Could we see the internet as a new kind of archive now? All these questions worked in our minds as we curated this exhibition. We did not have ready answers, but we left it for the listener to listen as they please, choosing what they wanted to hear, and see too (as we had videos as well, including films like The Bake Restudy of Nazir and Amy Catlin Jairazbhoy.), and then maybe go home with some of these questions on their minds too.

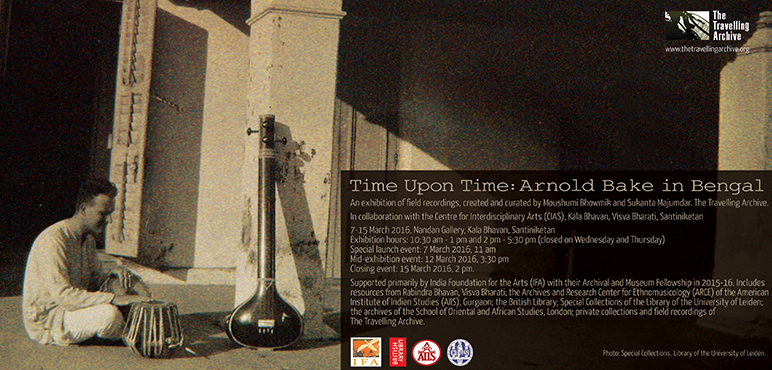

Poster of the exhibition

My own interest in the work of Arnold Bake has grown out of an archival recording I heard many years ago, sitting in a little booth of the British Library. I had no idea what I was listening to , but I was aware of some of the names of places and forms mentioned in the metadata and was quite intrigued by it all: ‘Kenduli, West Bengal. 1932-01. Female vocal solo. Bake’s notes: “Baul Gan. by Acintadashi, the sevadashi of Murali Das.” Cylinder made from badly broken and repaired original. Weak signal and surface noise.’ I knew nothing about Arnold Bake or his ‘cylinder’ recordings then, but was familiar with Kenduli and knew that January would be the time of the Kenduli mela in Joydeb. I also knew a little bit about bauls and their sevadashis or women collaborators in their spiritual practices. From then to now, especially with me being formally attached from 2013 to the School of Cultural Texts and Records of Jadavpur University, Kolkata, as a PhD student, working on ‘Arnold Bake in Bengal: The Politics of Archiving’, our research on Bake and our related field recordings have grown and spread out in many directions. In ‘Time upon Time’ we tried to share something of this work with our listeners.

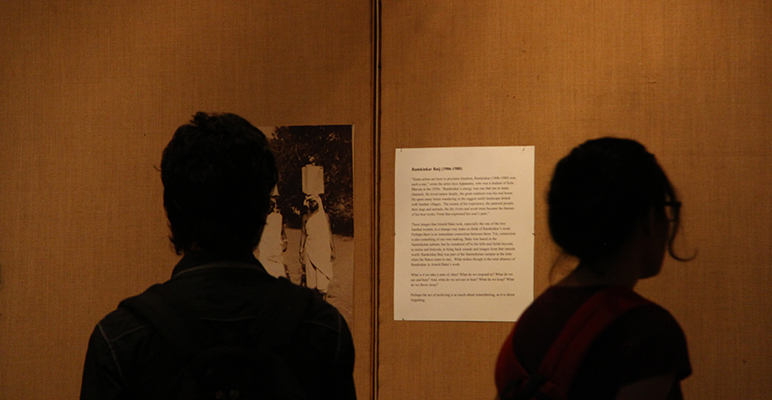

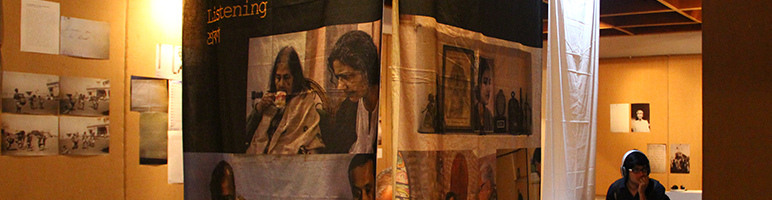

‘Time upon Time’ was mainly about listening, but it was also about seeing. And reading too. The walls of the gallery of Nandan were lined with images (Ronny Sen and Twisha Deb, photographers, were the main visualisers of this display), which were mainly blown up photographs, of photographs taken during our research at Leiden University. To them we added words from Bake’s letters, in translation (we were fortunate to have a young Dutch scholar from Utrecht, Jan-Sijmen Zwarts, interning with us for a few months). We had story boxes based on his letters. And letters as physical objects were copied and gathered in heaps at the corners of the gallery. On display were also letters found at Rabindra Bhavan, Santiniketan, mainly to do with Bake’s relationship with Tagore. There were also images we had got from private collections of people connected with Bake’s world in Bengal.

Within the space of the gallery we created walls, like unfinished houses, and each wall had its own pictures and each house its own story in sound, as created by Sukanta. The images printed on these walls were our own photographs from our field trips, as well as pages from Bake’s published works and letters. None of the images were captioned, as the idea was that the sound would tell the story of the image and the image of the sound, leaving gaps of course, for there are many gaps in our story-telling. Moreover, this was only a piece of work in progress.

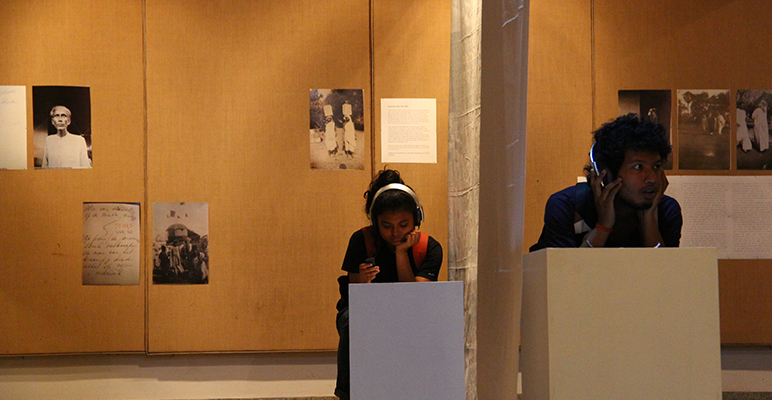

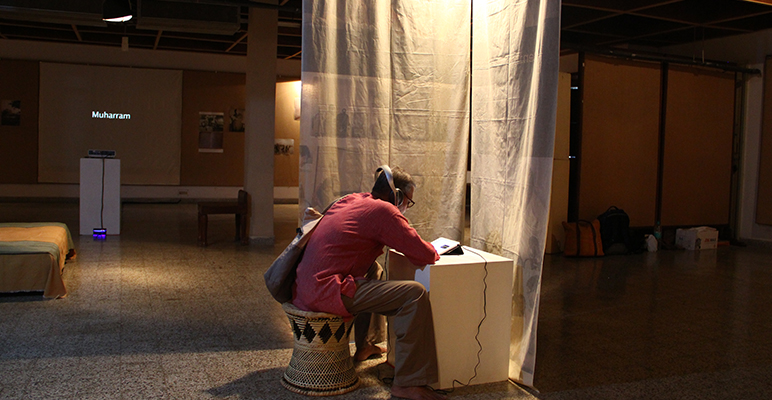

We had five listening stations with soundtracks in which voices from the past were in dialogue with voices in the present. There was also a projection on the wall of Bake’s silent footage from Santiniketan and elsewhere in Bengal, which we had got mostly got from ARCE, also some from ethnomusicologist Amy Catlin Jairazbhoy. As one listened through headphones, the image played over and over and the listener was left to make their own connection between picture and sound. The attempt for us was to try and ask the question of how we might listen to Arnold Bake today and if at all it was possible to hear him in our own work?

We hosted three events at our exhibition at two of which representatives from two of our archives were present (Dr Tapati Mukherjee, who heads Rabindra Bhavan in Santiniketan and Dr Shubha Chaudhuri, Director of ARCE), while on the final day there was music from the Mitra Thakurs of Mainadal, a family of musicians whose ancestors had been recorded by Arnold Bake in 1932.

The exhibition also opened up for us possibilities of new relationships, with individuals and institutions, such as Berlin Phonogramm Archiv. Meanwhile, British Library have repatriated Bake’s recordings to Mainadal and Chitralekha Chaudhury, since we first made contact with them, and they are now also engaged in their own research on Bake’s Bengal recordings, which is their collaborative project with SOAS. In 2015, when I was working in Leiden, Dr Doris Jedamski, then Curator of the Special Collections of Leiden University Library, and historian Dr Bob van der Linden (whose biography of Bake is due to be published in 2018), and I were informally talking about the need for connecting archives, institutions and individuals. who are all working on the same topic. There has been much talk, always, in Bake-research circles about the need for collating his wide ranging materials, scattered in so many archives. There has been talk on tracking, to use Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy‘s words, ‘the migratory path of Bake’s collections’. Perhaps it is from within all our individual efforts that the collective will emerge, some day.

Written by Moushumi Bhowmik

June 2017.

This exhibition engaged with the historical, aesthetic and social dimensions of archival sound recordings. The use of sound recordings, film footage, letters and photographs were purely for non commercial purposes and within the principle of fair use in Indian law and intended to further future intellectual and research interests in sound archives including criticism, review and creative transformations.

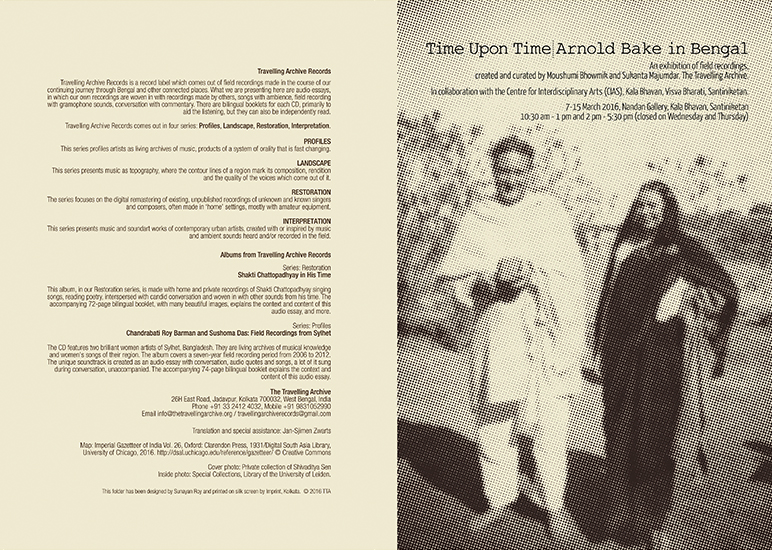

The exhibition folder

Exhibition folder: Front and back cover

Inside of the folder

Click on the image below to download the exhibition folder

This folder contains three essays in three languages; the Bangla and English written by Moushumi Bhowmik and by Jan-Sijmen Zwarts, in Dutch. There are also notes on the soundtracks and on the archival materials, which were exhibited. Here are some extracts from the essays.

Time upon Time: Arnold Bake in Bengal

You said, . . . you didn’t mind leaving behind

objects of desire

you had collected over twenty-five years. . .

Only the photographs you mourned

The beloved sepia of one family tree

Since you are the reason why your fathers lived;

But who’ll believe now

That you lived at all?

‘Poem for Joseph’, Robin Ngangom

‘Time upon Time: Arnold Bake in Bengal’, an exhibition of field recordings by The Travelling Archive, in collaboration with the Centre for Interdisciplinary Arts, Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan. At Nandan Gallery, 7-15 March 2016.

As such, Robin Ngangom’s ‘Poem for Joseph’, written about political strife and dislocation in Manipur, has nothing to do with our exhibition. Yet, in the sepia sounds of Arnold Bake’s wax cylinders of nearly 80 years ago, in our photos of his photos, in his writings, from 1937, ’48 or ‘63, his letters home to his mother written Wednesday after Wednesday from Santiniketan, in his concert notes, scribbles in notebooks, draft radio programmes, or in his soundless footage from Kenduli or Mongoldihi, it is this ‘family tree’ from the world of Arnold Bake which seems to give us shade. In this exhibition, fortunately for us, we do not ‘mourn’ the loss of the ‘beloved sepia’ of that family tree, but celebrate its presence in our lives. It gives meaning to our work; from it we claim a part of our ancestry. . .

. . .We first encountered his recordings in the archives of the British Library in London in those early days [2003], and have remained connected to his work ever since. . . . There are large overlaps between Arnold Bake and our work, both from a topographical and an archival perspective. This means that, in many ways, songs and sounds that are part of our work are drawn from the same well as Bake’s recordings all those years ago. This exhibition is thus an attempt to unravel the threads of archival material to demonstrate how past, present and future are intertwined. In 2013, we had created a piece of work for an art exhibition on early sound recording in India called Footsteps of Sound. In that work we keep coming back to two questions: How do we listen to Arnold Bake today? Can we hear him in our work? The point for us is this: that the ‘today’ of Footsteps is yesterday now; and in the interim, our listening to the world and to the world of Bake has grown and moved and become more layered as well as tangled up in time. (Watch Footsteps of Sound on Vimeo)

It is a strange feeling to listen to these wax cylinders. You listen once, listen again and slowly the sound grows on you. Physically and materially, time is written on these cylinders. The noise, the hiss of the machine, the cracks and crevices on the body of the cylinder, all reveal themselves in their sound. At first you hear little else besides the ‘noise’. Then gradually you hear more. This listening changes, not only because you can hear better and can separate the song from the other sounds, like separating grain from chaff, but also because the meanings of grain and chaff have changed for you in the meantime. You now know something about the machine, the details of the cans which Bake was sending to Berlin, the woman he was recording in Naogaon. Your listening changes also because you are more familiar with the story of the song; you know more about the time, something about the genre, the composer. Hence, when Chitralekha Chowdhury says she was taught by Shantidev Ghosh, you hear shadows of her teacher in her voice (although the particular recording in question was not a cylinder, but recorded on a reel-to-reel recorder). Or, when you have heard the Mainadal kirtaniyas sing for hours their Nandotsab or Niyomsheba songs, and you listen to a recording from the archives marked ‘Kenduli’ on their catalogue, then you think, this cannot be Kenduli, perhaps this was Mainadal, or maybe a team from Mainadal was singing at Kenduli? Such details you begin to hear despite the ‘noise’ which covers the surface of the recordings. . . .

Moushumi Bhowmik, 7 March 2016

Santiniketan.

বাংলায় আর্নল্ড বাকে: একটি ‘টান-ভালবাসা’র গল্প

‘শুরুতে শব্দ ছিল’। বিবিসির জন্য এক বক্তৃতামালার এমনই শিরোনাম দিয়েছিলেন আর্জেন্টিনীয় পিয়ানিস্ট এবং কন্ডাক্টর ড্যানিয়েল ব্যারেনবয়েম। আর্নল্ড বাকের সঙ্গে আমাদের সম্পর্কের শুরুতেও কিছু শব্দই ছিল, স্থান, কাল, পাত্রের সূচক হিসেবে—কিছু লেখা শব্দ, কিছু শোনা, কিছু যন্ত্রে ধারণ করা। ২০০৪-এর কোনো এক দিন, লন্ডনে বৃটিশ লাইব্রেরির সাউন্ড আর্কাইভে এটা সেটা ঘাঁটতে ঘাঁটতে ক্যাটালগে একটি রেকর্ডিং এর বিবরণে ‘কেন্দুলি’, ‘১৯৩২’, ‘অচিন্তদাসী’, ‘মুরলি দাসের সেবাদাসী’, ‘বাউল গান’—একই বাক্যে এইসব শব্দ দেখে খুবই কৌতূহল হয়েছিল। তখন লাইব্রেরির কাছে এই রেকর্ডিংটি শোনার অনুরোধ জানাই। আর শুনতে গিয়ে দেখি, ঘশঘশ শব্দে কিছু একটা ঘুরে চলেছে আর তার তলায় ক্ষীণ স্রোতের মতন কী একটা যেন সুর বইছে। খানিক চেনা চেনাই লাগে। ‘বাকে সিলিন্ডার কালেকশন’ বলে লেখা ছিল ক্যাটালগে। ব্যাপারটা খুব যে ভাল বুঝতে পেরেছিলাম, তা নয়; তবে এটুকু বুঝেছিলাম যে এই রেকর্ডিং বাকে নামের কেউ একজন ১৯৩২-এ, কেন্দুলিতে করেছিলেন।

সে-ই শুরু। আর্নল্ড বাকে নামের সঙ্গে সেই প্রথম পরিচয়, মোমের সিলিন্ডারের শব্দের সঙ্গেও। গত দশ বারো বছর ধরে একটু একটু করে সেই শব্দের বীজ থেকে একটা টানের সম্পর্ক গড়ে উঠেছে আমাদের আর্নল্ড বাকের সঙ্গে, এবং সেই প্রথম-শোনা শব্দ থেকে আরো অনেক শব্দের দিকে যাত্রা করেছি আমরা। শব্দ থেকে শব্দের দিকে, সময় থেকে সময়ে। এবং সেই শব্দ আর সময়কে বুনে, বেঁধে চলতে চলতে কোথায় এসে দাঁড়ালাম আর এর পর কোথায় যেতে পারি, ‘টাইম আপন টাইম: আর্নল্ড বাকে ইন বেঙ্গল’—আমাদের এই প্রদর্শনী তারই কিছুটা হদিস পেতে চাইছে। . . .

. . . গুরুসদয় দত্ত, ক্ষিতিমোহন সেন, অন্নদাশঙ্কর রায়, মহম্মদ মনসুর উদ্দীন, মায় রবীন্দ্রনাথ পর্যন্ত—বাকের সময়েরই সঙ্গীত সংগ্রাহক এঁরা সবাই। কিন্তু প্রত্যেকে প্রত্যেকের চেয়ে আলাদা। এঁরা সবাই এই ‘টাইম আপন টাইম’ গল্পের অন্যতম প্রধান চরিত্র। একজনের গল্প বললে অন্যজনের গল্পও এসে পড়ে। মজা লাগে ভাবতে যে, রবীন্দ্রনাথ যখন ‘পদ্মা’ বোটে চড়ে কাছাড়ি পরিদর্শনে বেরিয়েছেন, ১৮৯০-এর দশকে, তখন তাঁর যা বয়স, এই ৩০ মতন, বাকে যখন যাচ্ছেন নওগাঁতে, তখন তাঁরও ওই একই বয়স, ওই ৩০-এর কোঠায়ই। মাঝখানে কেবল ৪০টা বছর পার হয়ে গেছে। রবীন্দ্রনাথ সেই সময় মানুষের দৈনন্দিনের নানান ছবি ‘রেকর্ড’ করছেন তাঁর চিঠিতে আর ছোটগল্পে, বাকে তাঁর শোনা মানুষের কন্ঠ ধরে রাখছেন তাঁর মোমের সিলিন্ডারে আর ক্যামেরার ফিল্মে। আর আমরা যখন ঈশ্বরদী থেকে সান্তাহার জংশনে যাচ্ছি আরো ৮০-৮৫ বছর পর, তখন জল কমে যাওয়া চলনবিল আর হারিয়ে যাওয়া মাছ—যে মাছ মারতে বর্শা লাগতো—তার গল্প শুনছি। . . . ,

. . .২৫ থেকে ৩৫-এর একদল যুবক যুবতী, তাঁদের ঘর যেখানে, সেখানেই কর্মস্থল। তারই মধ্যে প্রেম-ভালবাসা, রেষারেষি, দ্বন্দ্ব। অমিয় চক্রবর্তীর স্ত্রী, হৈমন্তী, করুণাকে (কর্নেলিয়ার নাম গুরুদেব দিয়েছিলেন করুণা) চিঠিতে লিখছেন, তোমার কাজের লোকটিকে যদি দরকার না থাকে, তাহলে আমার বাড়িতে অমুকের জন্য একটু পাঠিয়ে দেবে? আজই পাঠিও। আর, কত টাকা মাইনে দিলে ভাল হয়, একটু জানিও। এ একান্তই ‘মেয়েলি’ ঘরকন্নার কথা। ওদিকে অনেক বছর পর অমিয় চক্রিবর্তী নরেশ গুহকে চিঠিতে লিখেছিলেন, বাকে মানুষটা ছিল পল্লবগ্রাহী। কেন লিখেছিলেন অমিয় চক্রবর্তী এমন কথা? কোথায় দ্বন্দ্ব ছিল? কেন আর্নল্ড বাকে ১৯৩৩-এর পর তেমন সরাসরি আর শান্তিনিকেতনের সঙ্গে যুক্ত থাকেননি? রবীন্দ্রনাথ যখন বাকেকে তাঁর গানের স্টাফ নোটেশন করার ‘চাকরি’ দেন, বাকে কেন তাঁর মা’কে লেখেন যে, সরাসরি গুরুদেবের সঙ্গে কাজ করতে পাবো এবার, শান্তিনিকেতনের অন্য লোকজনের সঙ্গে আমায় কিছু করতে হবে না, এতে আমি খুব খুশি?

‘টাইম আপন টাইম’ এইসব দ্বন্দ্বকে অস্বীকার করতে চায়না। নানা খন্ড মিলে যে সুর-শব্দের ছবি তৈরি হয়, তা-ই দেখার আর দেখানোর চেষ্টা করেছি আমরা এই প্রদর্শনীতে। আর্নল্ড বাকে এবং তাঁর স্ত্রী শেষ যেবার ভারতীয় উপমহাদেশে আসেন, ভারত তখন ভাগ হয়ে গেছে। অনেক কাল আগে যখন আর্নল্ড এবং কর্নেলিয়া বাকে প্রথমবার বাংলায় আসছেন, তখন লন্ডনের স্কুল অফ ওরিয়েন্টাল অ্যান্ড অ্যাফ্রিকান স্টাডিজের অধ্যাপক, সাটন পেজ আর্নল্ড বাকেকে জিজ্ঞেস করেছিলেন, বাংলায় যাচ্ছ, শ্রীচৈতন্যের বিষয়ে জানো তো? নাহলে কিন্তু রবীন্দ্রনাথকেও বুঝতে পারবে না, বাংলাকেও না। আর ১৯৫৬তে বাকে সুরেশ চক্রবর্তী মহাশয়কে লিখছেন, আপনি আমাকে এবারের কাজে একটু সাহায্য করতে পারবেন তো? আমার খুব ইচ্ছে, কীর্তন বিষয়ে আরো ভাল করে জানার, এবার আমি বাংলায় কাজ করে মণিপুরেও যেতে চাই। আমার কীর্তনের শিক্ষক, সাথী যাঁরা ছিলেন, তাঁরা প্রায় সবাই একে একে চলে গেছেন। নবদ্বীপ ব্রজবাসী মহাশয় প্রয়াত হয়েছেন, খগেন্দ্রনাথ মিত্র মহাশয়ের মন এখনও তাজা থাকলেও, শরীর অশক্ত হয়েছে।

আর্নল্ড বাকে শেষ পর্যন্ত মণিপুরে গিয়েছিলেন কি না, আমার জানা নেই। তবে কীর্তনের প্রতি তাঁর গভীর অনুরাগ ছিল। এই গান অনুরাগেরই গান। এই গানের প্রতি, বস্তুত বাংলার সুরের প্রতি আর্নল্ড বাকের এমন এক টান ছিল, যা তাঁকে ফিরিয়ে এনেছিল বার বার এই দেশে। ব্যক্তিগত সম্পর্ক, সাধারণ মান-অভিমান সেখানে তুচ্ছ হয়ে গিয়েছিল। এই টানই সম্ভবত বাকের প্রতি আমাদের টানের পিছনে কাজ করছে।

মৌসুমী ভৌমিক

১১ মার্চ ২০১৬

Time upon Time: Arnold Bake in Bengal

Een expositie van opnames en beeldmateriaal, gemaakt en samengesteld door The Travelling Archive

7-15 maart 2016. Nandan gallery, Kala Bhavan, Visva Bharati, Santiniketan (woensdag en donderdag gesloten).

Waar komt muziek vandaan, en waarheen is het onderweg? Deze vraag staat centraal in het werk van Moushumi Bhowmik en Sukanta Majumdar, het team achter The Travelling Archive. Het is een vraag waaraan we het antwoord altijd schuldig blijven, omdat muziek, zoals geluidsgolven weerkaatsen in de ruimte, verandert, evolueert, versterkt wordt, of verstilt met iedere luisterervaring. Desalniettemin is de vraag naar het komen en gaan van muziek een belangrijke. In hun reis door de ruimte kunnen muziek en geluid plaatsen aan elkaar verbinden en nieuwe ruimtelijke relaties scheppen; ze kunnen generaties overspannen en daardoor het verleden en het heden in elkaar over laten lopen. De religieuze kirtan, een eeuwenoude vorm van godsdienstige muziek van de lagere kasten uit Bengal, vond bijvoorbeeld zijn weg naar de radio, waardoor de muziek een brug werd tussen stad en platteland, rijk en arm, het verleden en de moderne tijd. . . .

Time upon Time is daarom meer dan een presentatie van Bake’s archiefmateriaal. Het is een poging het concept van archiveren onder de loep te leggen, en te kijken hoe een archief zijn weg baant door tijd en ruimte. The Travelling Archive is hiervoor, met ondersteuning van het IFA Archival and Museum Fellowship en een Scaliger Fellowship van de Universiteit Leiden, op zoek gegaan naar de oorsprong van Bake’s opnames en nieuwe opnames gemaakt op plaatsen waar hij geweest is. Op deze manier stapelt archief zich op archief, heden zich op verleden, en wordt de blik gericht op de toekomst van verzamelen, archiveren, en interpreteren.

. . . Time upon Time is bedoeld als een klankbord en een interactieve ervaring van een ‘work in progress’. Deze zin van progressie brengt de expositie tot uiting door de aanwezigheid van opnameapparatuur in de expositieruimte. Bezoekers worden uitgenodigd om hun eigen muziek, beelden, en verhalen te delen en zo onderdeel te worden van een levend archief.

Jan-Sijmen Zwarts

Vertaler/schrijver in samenwerking met The Travelling Archive

Opening ceremony: Chitralekha Chaudhury and Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur

The soundtracks

Research and concept by Moushumi Bhowmik

Created by Sukanta Majumdar

The original Bengal recordings of Arnold Bake can be heard on the Arnold Adriaan Bake South Asian Music Collection, British Library.

Liederen van Gurudev /রবীন্দ্রনাথের গান

Soundtrack created with Arnold Bake’s 1930 Pathe recordings of Tagore’s songs in his own voice, and his 1956 recordings of Tagore singers Chitralekha Chaudhuri and Indira Devi Chaudhurani.

Additional recordings used are Shantidev Ghosh’s ‘Amala dhabala pale’ and Dinendranath Tagore’s ‘Megher pore megh’.

Source: www.youtube.com, www.saregama.com respectively

Translations and main voice-over for this track: Jan-Sijmen Zwarts

Additional voice-over: Moushumi Bhowmik

Kirtan / কীর্তন

This soundtrack uses Arnold Bake’s recordings of Nabadwip Brajobashi in Calcutta (1932) and kirtan in Mainadal (1933) and Kenduli (1932), as well as The Travelling Archive’s 2015-16 recordings in Mainadal. Additional music used: Sukanta Majumdar’s Murshidabad kirtan recordings, 2012. Voice-over: Moushumi Bhowmik.

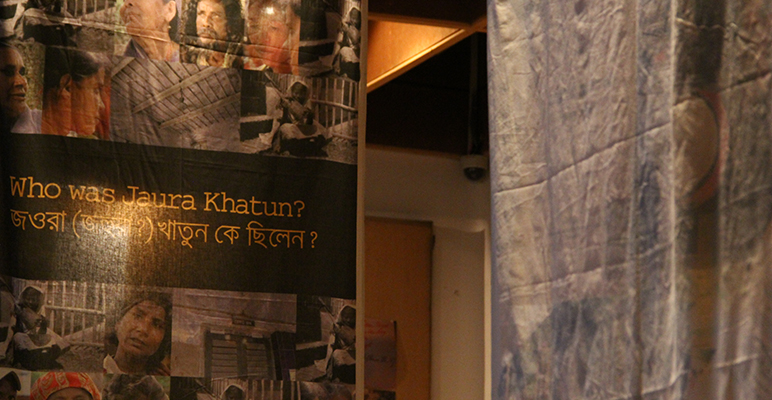

Who was Jaura Khatun? / জওরা [জহুরা?] খাতুন কে ছিলেন?

This is a story of a name that we find in the catalogue of an archive. It is, what the filmmaker Philip Scheffner would perhaps call ‘a ghost story’.

It uses Bake’s 1932 recordings from Kenduli and Naogaon and The Travelling Archive’s recordings of Mahmuda in Mahasthangarh and Shamsul Fakir in Bagolpara, Durgapur, Rajshahi (2015)

Voice-over: Moushumi Bhowmik

The Story of the White Wall / একটি সাদা দেয়ালের গল্প

This soundtrack is made with recordings made at Chitralekha Chaudhury’s house. When visiting her, we introduced her to her 1956 recording from the British Library. She told us the story of her mother’s fresco in Dhaka. Her mother, Chitraniva Chowdhury, was one of the first female students of Kala Bhavan and an accomplished artist in her own right. From Chitralekha the story went to Dhaka, where Chitraniva’s fresco once adorned the walls of what is now the storage room of a water filter distribution firm.

With additional research by Nisar Hussain of the Department of Fine Arts, Dhaka University. Also includes voice of Nisar Hussain.

Listening / শ্রবণ

This piece is made of seven separate soundtracks.

1. Mainadal. We took Bake’s Mainadal recordings of kirtan to Mainadal several times between 2015 and 2016.

2. Supriyo Tagore. We took a recording made by Arnold Bake of Indira Devi Chaudhurani in 1956, to her brother’s grandson, Supriyo Tagore, in Santiniketan in January 2016. Supriyo Tagore’s eyes welled up and his voice broke to listen to Bake’s recording. Interestingly, there is an interview the eminent scholar and translator, Khitish Roy, had taken of Indira Debi Choudhurani in May 1960 on the occasion of Rabindranath’s centenary, which was broadcast on AIR, in which she also recalled this recording session with Arnold Bake.

3. Haimanti Dutta Gupta. We went to Haimanti Dutta Gupta in Calcutta in March 2016, and showed Bake’s photographs of her mother, Jaya Sen and her father Motru Sen.

4. Bithika and Priyam Mukherjee. In January 2016, we shared Bake’s recordings of Tagore’s songs with old ashramites, Bithika Mukherjee, who is also sister of the famous Rabindrasangit singer Kanika Bandopadhyay, and her son and Tagore singer, Priyam Mukherjee.

5. Shivaditya Sen. We took Bake’s photographs of Kshitimohan Sen and their correspondence, to his grandson Shivaditya Sen in Santiniketan in January 2016.

6. Seema Acharya. We went to kirtan singer Seema Acharya’s home in Calcutta in February 2016. Acharya was a student of Chhabi Bandopadhyay, who was in turn a student of Nabadwip Brajobashi, who taught Bake. We went to her with Bake’s recordings of Brajobashi. We also had with us English composer Oliver Weeks’ playing and singing of Bake’s notations of kirtan.

7. Mongoldihi. We took the Mongoldihi footage of Bake to the family of the Thakurs, who organise the kirtan for Balaram, during their Ras Utsav in November 2015.

Some other photos of the exhibition

A video by Ronny Sen

A video inspired by Moushumi’s rendition of the famous Tagore song, Jibon Jokhon Shukaye Jaay. Watch on Vimeo.

Ronny Sen is a friend of The Travelling Archive. He is a renowned photographer.

Check the links below to see more of his works.

http://ronnysen.photoshelter.com/index

https://www.instagram.com/ronnysen/?hl=en

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-37426714